Moving to Canada Showed Me the Country’s Dark Side|People wait in long lines to see a doctor in Canada.|The grisly truth about Canada's residential schools is finally coming to light.

Moving to Canada Showed Me the Country’s Dark Side|People wait in long lines to see a doctor in Canada.|The grisly truth about Canada's residential schools is finally coming to light.

Moving to Canada Showed Me the Country’s Dark Side

“If Trump wins, I’m moving to Canada,” is something every good American progressive said in the months leading up to the 2016 election. However, very few actually did this. My husband and I were two of them. The environment in the South, where I was born and raised, had become so politically charged. While we had become part of a tight community and formed several close friendships in our more progressive town, a land flowing with delicious pimento cheese and barbecue, we were fed up with hearing and seeing so much support for Trump, fewer gun laws and a border wall. But we weren’t expecting Trump to win at all. In fact, we set up a small party in our apartment to celebrate as we watched the election results come in. By midnight, I went to bed with a sinking feeling in my stomach. How could this be happening? I felt like I was living in a bad dream.Needless to say, we looked up the process for immigrating to Canada, and it was not as complicated as you’d think. We’d visited a few times and liked what we saw. Within a few months, we had our papers, and my husband had a job offer, so in mid-2018, we left everything behind in my home state and moved to British Columbia. The move was extremely difficult, but I remained hopeful that I’d find friends soon and build a life similar to the one I was leaving behind in a place where they had things figured out much better. Boy, was I naive.

Within the first two weeks, my husband’s car was robbed.

Canada Isn't the Progressive Paradise We Expected

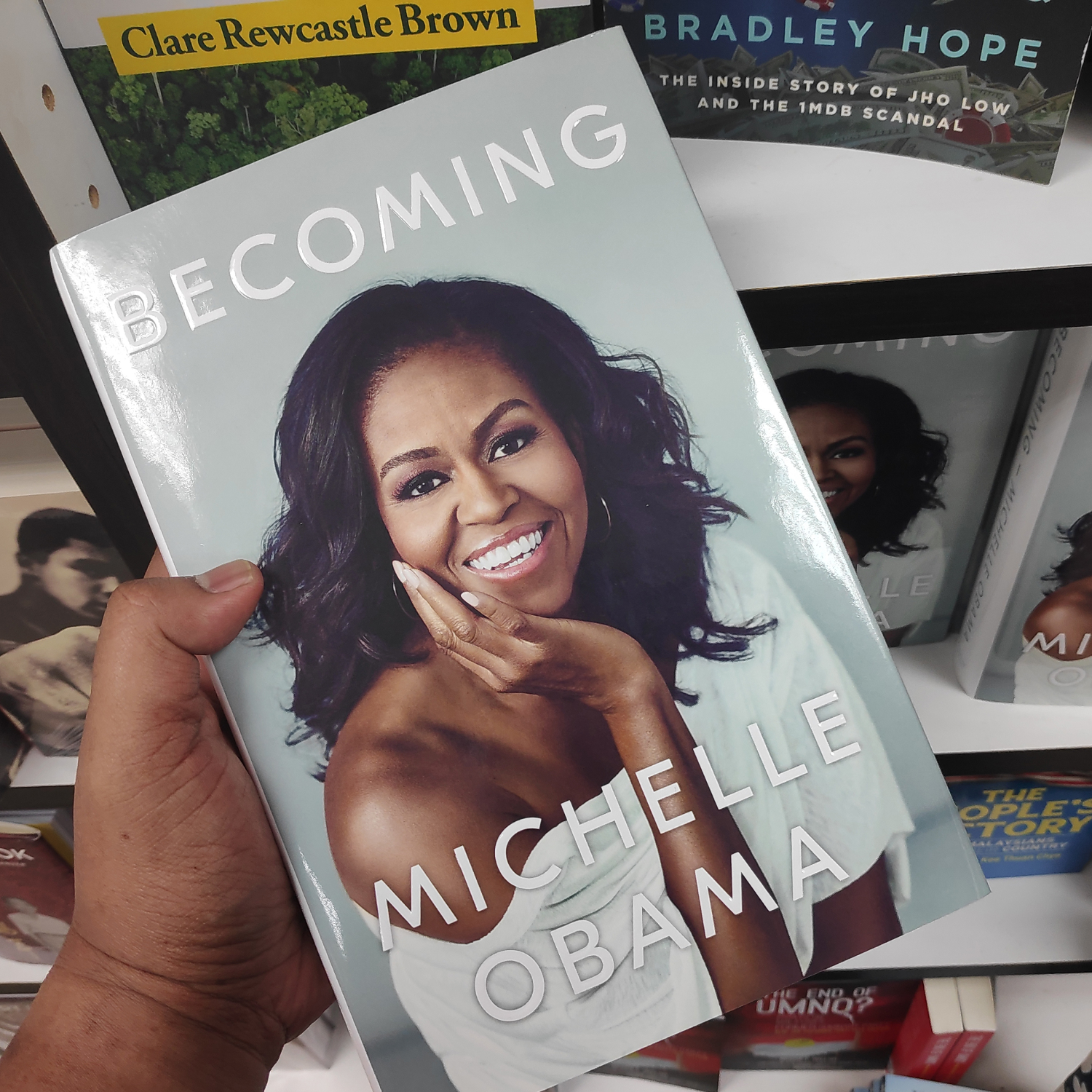

We left the comfy 800-square-foot apartment we were renting for $850 and moved to a 540-square-foot apartment in a similarly-sized city for almost twice the price. Within the first two weeks, my husband’s car was robbed inside our private parking garage. He called the local police to report it, and they told him they couldn’t come that day because they were understaffed but could come the next day if he called again. Looking back, this was definitely a red flag. Theft seems to be the crime of choice here. Just a few weeks ago, I was in the mall when someone swiped a stack of Lululemon clothes and made a run for it. None of the store employees even flinched, as if this happens every day. It’s also not uncommon here for people to get randomly attacked by a mentally ill person. What’s worse is that it is illegal to carry anything that could be used as a weapon to defend yourself, including pepper spray.In the U.S., I’d never seen drug deals or injections happening in plain sight. Here, it’s visible everywhere you look. A few weeks after my move, I came upon something on the sidewalk that stopped me in my tracks. Someone had stabbed a needle into a piece of dog poop. This, too, felt like a sign.Recently, I had my first experience interacting with the Canadian universal healthcare system. Unfortunately, there’s a huge doctor shortage in BC. Very few people manage to get a family doctor, and when one retires, there is often not another one to replace them. So, the only options are to visit a walk-in clinic or go to the emergency room. I had a very sore throat, and not wanting to take up a space at the ER with a non-emergency, I called a couple of clinics and was told there was no way to get in during the day and that I’d have to arrive before opening time and line up. So the next day, I got up early and lined up 30 minutes before the clinic opened. The lady behind me said, “I really hope I get in this time! I came early twice this weekend, and they wouldn’t take me.” I started to get nervous about whether I’d get in too. When they opened at 8 a.m., the nurse came out and counted us (there were about nine people) and then told us we were the only ones that would get in. Whew! I felt relieved. The nurse then put up a sign that read, “Zero Openings, Full Capacity.” The lady behind me was so excited that she would finally get to see a doctor. I couldn’t help but think to myself how wrong and backward this all felt for a first-world country. I’ve since encountered numerous stories in a local Facebook group about people not being able to get access to the health care they need. Many of these people need urgent care, but there is little sympathy in an overloaded system.

Canadian Culture Is Built on Hypocrisy

One of the biggest things I learned within the first few months of our move is that it is incredibly difficult to make friends in our province. We tried Meetup.com, went to local events, and participated in different classes and lessons. Out of ten people that invited us to their homes, only one of them actually followed through on it. I’ve even gotten some Canadians to admit to me that they make invitations as a form of being polite but have no intention of following up on them. What? This is not what I was used to back in the South, where even people you’ve recently met invite you over to their home for supper. Here, it’s extremely difficult to make a connection that goes deeper than the surface. As an immigrant, I realized the only way to emotionally survive is to seek out foreign friends. People here are polite for sure, but they are not open and welcoming like I was used to. When I first arrived in BC, I was immediately struck with how “in your face” the Indigenous symbols and cultural references are. I was quite impressed with this because, in the U.S., Native Americans are rarely acknowledged. A couple of months after my arrival, I attended a local community event. They started the event with a territorial acknowledgment, which is standard practice in Canada. “We would like to thank the Coast Salish peoples on whose unceded, traditional territory we are gathering together.” “Wow,” I thought. “They are actually acknowledging that the land we’re on is stolen and we’re privileged to be here.” As an American, this was a completely new concept for me. I was moved.Over time, I heard the term “residential schools” come up occasionally. I began to understand that they were a bad thing, but I had no idea the extent of the horror they really were. Nobody really talked about specifics. Only when the graves of hundreds of children were discovered at residential school grounds in mid-2021 did I come to realize the extent of the crimes the Canadian government had committed against Indigenous children. I was mad. Why was this not common knowledge? Why weren’t people talking about this before? Why wasn’t the government looking for these children they knew never came home from the residential schools? I found out that the government had previously ordered a very thorough investigation of residential schools, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission wrote very long, extensive reports on the topic just a few years before these discoveries. But what has really been done since that? I’ve now come to realize that the incorporation of all these symbols and acknowledgments is actually a very elaborate facade, a way for the Canadian government to “apologize” and admit they did bad things to the Indigenous peoples in the past while continuing to ignore the extreme injustices against Indigenous peoples that exist to this day. This attitude is the embodiment of Canadian culture. It’s baked into how everyone relates to each other. The only way they know how to communicate is politely—so careful to not offend anyone. To say whatever they need to, even if they don’t mean it in the slightest, in order to maintain that facade. For example, using the word “Indian” is strongly looked down upon, while systemic racism against Indigenous students in the educational system has been ignored for years. It doesn’t make any logical sense; only in that we must do what we must do in order to appear good without actually being good.

In the U.S., I’d never seen drug deals or injections happening in plain sight. Here, it’s visible everywhere you look.

The U.S. Has Its Problems, but at Least We Don’t Hide Them

There have definitely been some moments where I’ve been grateful to be here. Specifically, during the pandemic. Because we’re more isolated, our COVID case counts have remained relatively low, and I’ve felt very safe. But when the vaccine started to roll out in the U.S., Canadians were left waiting and waiting. When most of my friends in the U.S. had been fully vaccinated by April, I was still waiting to get my first dose. We weren’t eligible to get it until the end of May, and then we were told we’d be contacted for our second dose in three months. Three months?! We knew this was not what the vaccine manufacturers recommended. The government was playing it down and also told us it was OK to mix vaccines. So, we hightailed it out of there at the end of June to snatch our second dose in the States before returning to Canada to ride out whatever wave may come next. I promise I’m not trying to trash Canada. I simply want to expose it for what it is. The U.S. is far from perfect—that’s why we left in the first place—but its faults are pretty well-known around the world. We don’t hide them. On the other hand, Canada pretends to be perfect, and it flaunts that facade—a chilly, multicultural paradise with a sleek universal health care system and a sensible prime minister, overflowing with happy, friendly people who say “Sorry!” and “Eh” a lot. At least that’s how I saw it. But not anymore.