Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

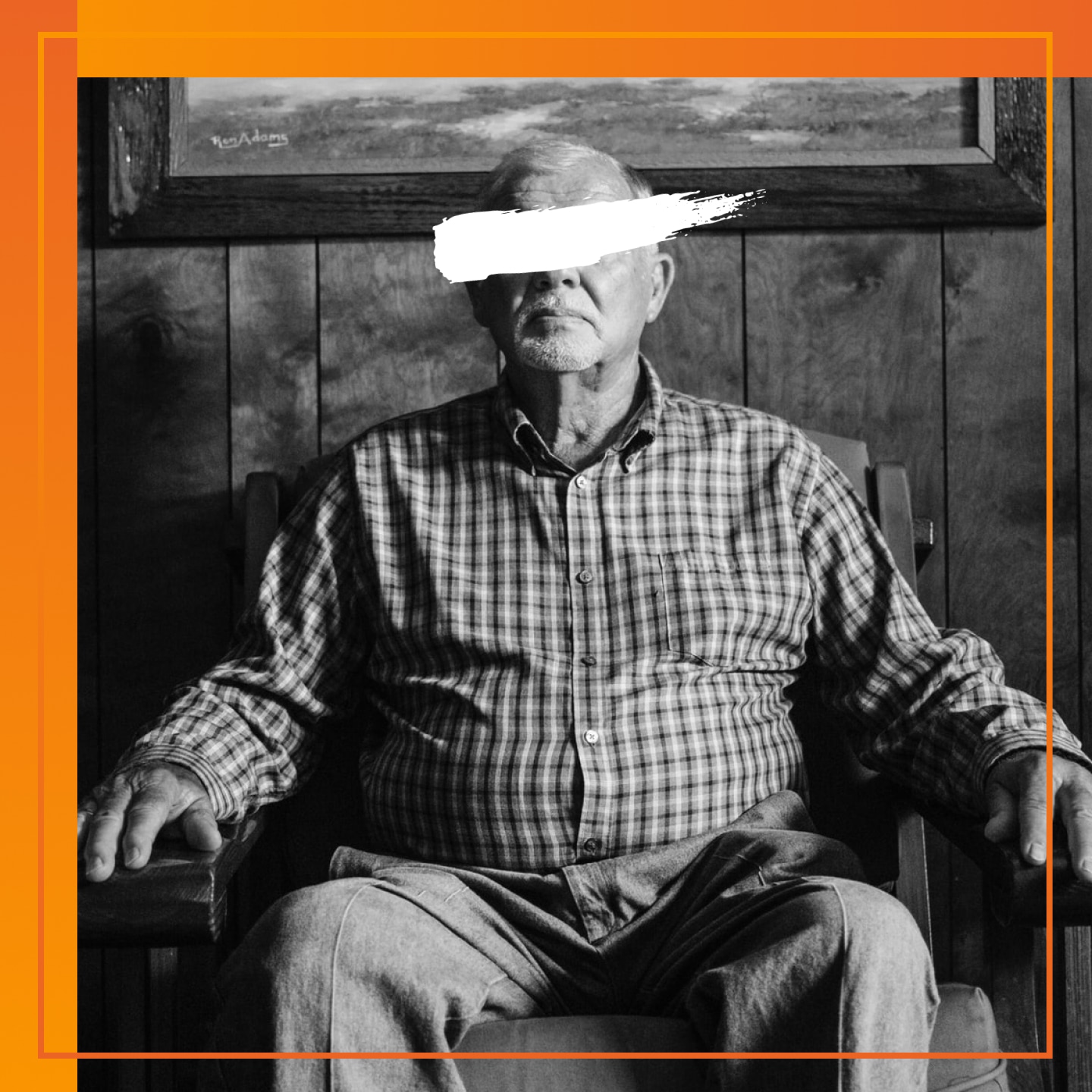

I Was Sexually Abused as a Child. My Teachers Should Have Known.

In 2002, during a time when I had been a target of sexual assault at the hands of a family friend for two years, British parliament passed the Education Act. The law, among other things, gave teachers the legal responsibility of safeguarding their students. Teachers now had a legal and professional obligation to be vigilant for signs of abuse in their students, and to report these to the correct authorities when noticed.

I was seven years old. The abuse would continue for three more years, before my own disclosure brought it to an end.

During that time, this man, who meant so much to my parents and was so trusted by all my adult family, took my virginity, my fertility (thanks to internal scarring), and a series of images that I will never know the location of. My parents put me in therapy, and in my teenage years I came up with other ways to cope, through a group of other deeply damaged teenagers and incredibly risky sexual behavior. These two elements of my life came together for two years, in a relationship with my high school boyfriend. He fell comfortably within the definition of “deeply damaged,” and his coping mechanisms were largely violence, rape, and badly played guitar—all aimed at me.

I moved away; life went on. I went to university, met a good partner, started to travel, and within a few years of graduation, I found myself studying again, this time for a PGCE (the standard British teaching qualification). Before we were allowed to actually have contact with students and work in a classroom, we had to undergo safeguarding training, otherwise known as child protection training.

I don’t remember exactly which PowerPoint slide made me leave the room, but I do remember a slowly approaching march of dread and nausea, as we covered all the subtle signs of a child being abused. I remember running out the room and vomiting onto the curb. I remember explaining to my very confused lecturer that I had been a victim of CSE (child sexual exploitation, the government language for what happened to me). He was as comforting as a middle-aged, middle-class, British man could be. He reassured me that all I had to do was tell people; I would be able to undergo the training in a setting that made me feel safer.

I’m a teacher now. I know they knew, because teachers always know what the students are saying.

I couldn’t be exempted, however, and that made every part of my brain shout. Were my teachers taught the same things? Did they have the same responsibilities? Should they have known?

The short answer is yes. The document had a different name, and it has been added to and tweaked since, but the answer is yes. It is, as always, more complicated than that. In primary school, I was younger, and while I am sure I must have shown signs of abuse, I was also a very strange child. I was autistic with sensory issues, a hatred for socializing, and what appeared to be a deep love for screaming until I vomited. I imagine my teachers attributed any odd behaviors I had to that.

However, did they not notice the bruising when I got changed for P.E.? The way I went limp when people touched me? It was clear I didn’t like the touching, but I also put up no resistance. Someone, anyone, of the dozen or so teachers and teaching assistants that were responsible for me over that time period should have had enough of an inkling to make even a cautious report. A report that could have saved me years of anguish and pain. I have sympathy for those teachers. I don’t find their neglect reasonable, but I can understand.

High school, less so. In fact, not at all. I will never forgive them. Everyone knew what my boyfriend was doing to me—everyone. I was openly bruised across my arms and face and neck, visible in my uniform. He attacked me on school grounds more than once. On one occasion, he broke a rib on school property. We were both in our uniform and he drove his polished black lace-up shoe into my chest until I thought I was going to die. Teachers knew. They heard the whispers; there is no way they didn’t. All the students knew he had raped me. I saw it flit around every classroom I went into.

I’m a teacher now. I know they knew, because teachers always know what the students are saying, especially the things they think they are keeping the most quiet.

Those teachers made no report. They didn’t call my parents, let alone his. Instead, a group of four teachers—around a month before exams started, a week or so after I had finally ended things, and a few days after he had cut my name into his flesh as some sort of statement of love— sat me down and told me to get back with him. Start dating him again. Because exams are coming up. Because the breakup will distract him. Because it’s his future. Because you’ll do well either way, but he really needs it.

I guess if you asked them, they would claim they didn’t know, that they just wanted the best for everyone, but they didn’t.

As a teacher, I cannot forgive the negligence of my primary school teachers, or the willful ignorance and disregard of my high school teachers. Over my time at school, I can name more than 30 teachers who taught me directly. Those are only the teachers that I remember. That’s at least 30 trained professionals, with a legal expectation, who allowed me to suffer. There are very few ways someone with my story can feel they have received justice, and this is just another part of my story that will never be made right.