The Doe’s Latest Stories

The Harsh Realities of Climate Change and How to Respond

I’ve been working on climate change off and on for decades. During that time, I’ve found that the general public doesn’t always understand the realities of the situation, and neither do many of those who are most active about responding to it. I’ve taught college courses on the subject, and even my science and engineering graduate students are often misinformed about it. I’ll admit that I’ve been fooled by many of the issues myself. It’s taken chats with thoughtful leaders in the field for me to really understand the situation.Much of our climate change strategy so far has focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Some of these, like methane, have a greater impact on climate change than carbon dioxide. In the very first report I worked on, back while I was still a student in the '90s, we came up with well over 50 ways to reduce these greenhouse gas emissions. Thirty years later, we still need to reduce the number of greenhouse gases emitted globally by half before 2030 in order to get to “net-zero” by 2050. The current list of what actions we could take is in an Exponential Roadmap 2030. Its recommended actions aren’t significantly different from what was in the first report I worked on. The reality is, we just don’t have the will to do them.

We need to reduce the number of greenhouse gases emitted globally by half before 2030 in order to get to net-zero by 2050.

Clean Energy Is a Challenge in and of Itself

Let’s take electrical cars as an example. The Exponential Roadmap recommends that by 2030, 100 percent of new car sales worldwide be electrical or plug-in hybrids. But electric cars aren’t the easy fix they’re often portrayed to be. Yes, electric and plug-in hybrid car sales are increasing, but looking only at the growth curves can be deceiving. Overall, they make up fewer than one percent of cars on the road globally as of 2019—just 7.2 million out of 1.5 billion! Can you imagine getting to 100 percent in less than a decade? Pure logic tells you it’s just not going to happen.And then, of course, there is the challenge of renewable energy sources. If the electricity for your electric car comes from fossil fuel, you’re not actually helping the environment by driving it. When I ask students in classes I teach on energy and environmental policy how much renewable energy they think we use, the answer is typically around 50 percent. As is the case with electric vehicles, the number is increasing, but it’s still only 28 percent globally, which means that even if we had all those electric vehicles on the road, the electricity powering them probably wouldn’t come from a renewable energy source. So again, we aren’t making real headway.So, I’m sure you’re wondering, is it hopeless? What can we do?

We need to advance our use of variable energy sources like wind and solar that don’t generate power continuously.

The Biggest Climate Change Challenges We’re Facing

First of all, a new set of technologies is on the horizon called carbon dioxide reduction technologies. Essentially, they take carbon dioxide out of the air. These technologies can take many forms including biological methods, such as storing carbon in forests, agricultural soils or the ocean, and using biomass as an energy source. To me, the most interesting technological method is what’s called “direct air capture”—think of it like a vacuum that takes air in, scrubs the CO2 out of it, and then stores the CO2, either underground or in products like cement. Another option is carbon mineralization. This would speed up what is now a natural process where certain minerals react with air containing CO2 to form solids. All of these methods are expensive and have additional challenges, but they provide new hope for investigation.Second, we need to advance our use of variable energy sources like wind and solar that don’t generate power continuously. In this case, we need to focus much more on ways to store this energy so we can deploy it when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine. Think about this like the battery for your phone—when it's charged, it's great, but when you’re not near a place to charge, you’re in trouble. The same is true for wind and solar energy in terms of their ability to provide a reliable source of energy.Finally, we have to tackle the social challenge, which is less about whether or not people believe climate change is happening than the degree to which they’re willing to pay to fix it. This doesn’t just mean the people you probably assume it does. We all make decisions every day that result in greenhouse gas emissions. Although corporations get most of the blame, it’s really all of us.

Understanding and Responding to Climate Change Are Very Different

Those of us who support immediate action on climate change need to listen more to those who don’t. We are often biased against such individuals, thinking that they don’t understand climate change and its impacts, and that if we just “educated” them, they would “believe.” The actual picture is far more complex. More than 80 percent of Americans believe global warming is probably happening, and that moderate government action is necessary—more Americans than voted for president-elect Biden, who received more votes than any other president in history.So, we have to dig deeper. Only about 50 percent of this same population thought global warming would hurt them moderately. The next question is, how much are they willing to pay for action on climate change? When President Trump wanted to freeze an Obama-era automobile fuel efficiency standard that would have doubled fuel economy to 54 miles per gallon by 2025, survey respondents were told it would decrease the price of cars. With that information, just under half supported the freeze. And so, again, we have our divided nation.

What is the Value of Climate Change? It Depends on Whom You Ask

In a simpler experiment, I often ask my students a question that was asked of me and other colleagues by a now well-known economist while working on that first climate study so long ago. First, picture the dollar amount of your current income. Next, think of all the societal problems that we face as a society including challenges like homelessness, hunger, health issues and air and water pollution. Finally, if you knew that climate change was a certainty, what percentage of your current income would you be willing to spend on responding to climate change?I’ve asked this answer of audiences small and large, rich and poor but almost always scientists, engineers, and health professionals. Answers typically range from around 0.01 percent to 10 percent. There are also typically two outliers, at zero percent and 20 percent. So even if we can agree it’s happening, and we’re knowledgeable about the issue, we still can’t agree on price.In sum, some believe the costs of responding to climate change today are a “luxury good.” If you’re unemployed, having difficulty meeting your basic needs of housing and food, this can well be the case. So, be forgiving, and try to understand others’ economic needs. If your kids are hungry, climate change may not be number one on your priority list.

Social Media Censorship Isn't a Partisan Issue

I got into the world of online news publishing in the last months of the industry’s “Wild West” period: before fact-checkers, Facebook jail and endless verification red tape. Back when a guy on his laptop could look out at the digital landscape like Davy Crockett on the wild frontier and truly feel he could change the world. Ah, the good old days.That was before the industry’s corporatization.The seismic shift in the flow of information began taking effect in 2017 but really hit its stride in 2018. It was a matter of social media companies—spurred by a political left that was outraged at the election of Donald Trump and at the right’s apparently effective usage of social media to enable that victory—deciding that it was time for the frontier to close. Sure, they made it seem like a good thing. They made us think it was all about deleting “Russian bots” and stopping “foreign interference.” They told us their only concern was stopping “disinformation” to create a happy-go-lucky online utopia where ideas and information would flow and mingle peacefully. They promised us Looking Backward. Instead, we got Panem.

But then our ship hit the iceberg.

At First, Social Media Helped Grow Many News Outlets

When I began writing, the digital news field was dotted with tiny, independent publishers as far as the eye could see. You could peruse your social feed and find news site after news site that your average person had never heard of, and yet were individually all getting enough traffic to actually afford small, dedicated staffs.I got my start at one of these—an outlet that might not have boasted a lavish New York office or its own helicopter, but did well enough with its regular stream of daily articles to give freelancers like me, a dad with a handful of young kids, a much-needed side income.The key was its sizable social media following, particularly on Facebook, which is where readers consumed independent publishers in those days. The outlet I was writing for had managed to amass close to a million “likes” on its Facebook page, which translated to clicks and revenue from display ads.For many writers in my situation—no college diploma, but a knack for the written word and a zest for the grit it takes to cut it in the highly competitive freelance market—this kind of gig was a way of getting a solid footing into the writing industry.Contrary to the picture painted by those too trusting of the establishment media, we operated with high journalistic standards and integrity. Our ragtag band of writers and editors fact-checked, proofed and reviewed like a germaphobe washes his hands. Articles that weren’t based on original reporting featured proper sourcing and were closely scrutinized against plagiarism.My experience there allowed me to land a second gig with an outlet that had an even bigger audience, a website founded and managed by a husband-wife team who used the share of their earnings to supplement the income from their small family farm.Eventually, I scored a full-time salaried position with a larger independent publisher that made enough money to rent an office not too far from where I was living. Things were going well.But then our ship hit the iceberg.

New Algorithms Hid Independent Publishers and Censored Their Posts

It started with diminished reach. In late 2017, Facebook changed its algorithm to deprioritize news feed distribution from pages (as opposed to friends’ personal profiles). This resulted in a massive engagement drop. I saw it with my own news page, which I had created to share my articles. It had been getting as many as 5,000 likes per post, with a following of a few thousand, but now I eked out, at most, 1,000 likes per post (and usually only about 100) even after my following doubled.Who was hardest hit by the change? It wasn’t the corporate outlets like CNN and Fox News, which leverage their universal name recognition to churn out sustainable levels of direct traffic. It was the smaller players who didn’t have that kind of brand recognition and who had been using social media’s unique, affordable audience building tools to make up for it.While Facebook assured us these changes were intended to make their user experience more “personal,” it’s safe to assume they knew how damaging it would be to the underdog publishers—the publishers the establishment blamed for the rise of Trump.It’s the same reason the social giant scrapped its “Trending” section, claiming the feature boosted “fake news” (read: non-liberal outlets) more than it did “authentic news” (read: liberal outlets). It didn’t help that “Trending” would often promote stories critical of Facebook.But the shakeup didn’t end there. Facebook implemented difficult-to-navigate rules for running ads about politics (which encompasses most news agencies) and began purges that censor and flat-out delete anything deemed problematic, whether it alleged “hate speech” (which often means taking a conservative viewpoint on an issue) or “misleading information” (which typically refers to facts The New York Times and New York Post don’t agree with).Inevitably, many of the mom-and-pop publishers, like some of the ones I’d contributed to, went under. Thankfully, I found a different opportunity when I saw the writing on the wall, putting my experience scribbling about politics to work in the field of political consulting.Even bigger names were hard hit. And it wasn’t just conservative outlets that were affected. HuffPost, once a reigning powerhouse in online news and opinion, fell from grace in large part due to crackdowns across several social platforms.

The left’s distaste for Trump and his supporters led them to cheer on the billion-dollar corporate news outlets.

Silicon Valley Wants to Keep Everything in a Safe Middleground

Who benefited? Again, it isn’t just a matter of left vs. right. Fox News saw just as much of a boost as CNN under algorithm changes thanks to being an “authentic” news source. What’s the uniting factor? Corporatism.Unfortunately, the topic of social media censorship and the lack of Big Tech accountability has become a partisan issue, devolving into nothing more than jeers at “dumb conservatives” making echo chambers on Parler. But there’s much more at stake than that.The political left in America has always rightly understood the dangers that corporations, when uncontrolled, can pose to a free society. After all, a corporation is not a person; it’s a legally-created entity that is granted immunity from liabilities that an individual would normally face for his or her business practices. And so liberals generally have sought to stand up for “the little guy” by demanding accountability of multinational corporations.But on the issue of social media, the left’s distaste for Trump and his supporters led them to cheer on the billion-dollar corporate news outlets dominating the information flow at the expense of the little guys.These big outlets, along with their Silicon Valley allies, claim they want to combat online “extremism.” But who are they to decide which views are extreme and which aren’t? What they really want is to diffuse all wrong-think on both the left and right sides of the spectrum and keep everyone thinking within a limited, acceptable space—the safe “middle ground” that poses no threat to the ruling establishment.Eventually, the grassroots of left and right are going to have to learn to work together if we don’t want to wind up as nothing more than two sides of the same coin in the pocket of the corporate elites.

Tech Companies Have Agendas; One Silenced My Conservative Voice

For a conservative Christian, working for a large tech firm was a dream that slowly turned into a moral nightmare. I was introduced to the world of technology in 2014. I had just abandoned a lengthy health career because of a coordinated media attack on my writing, business and relationships that didn’t stop for years. While I worked on defending my reputation, I found a new career at a growing technology company that claimed "inclusion" as their mission. This was absolutely true in 2014. But things change.I started out in simple sales, where the ability to make money was unbelievable. I was able to pull in six-figure checks just to provide people with a product they already wanted. And I was quickly learning how to climb the hierarchy inside a growing public firm. By 2016, I was provided every resource I needed to be a successful leader within the organization. I worked in every position I could within the company to learn. I was a salesperson, manager, hiring manager, district manager, operations manager and more. I made hiring decisions for numerous retail locations and I hired candidates from every race, gender and religion to fill these spots using the merit-based system I believe in.That merit-based hiring system works. The stores I controlled were the top stores in the nation at the fastest growing tech company in America. Soon, I was getting attention from every executive in the firm, and I was being groomed to run a larger part of the company. My paychecks were growing. My court case from my earlier life was settled, and I was pardoned by the state government. I adopted my son, who was fatherless, to give back to my community. I met my wife while at work. Everything seemed perfect. I had stability for the first time in my life thanks to the rise of technology sales in America. However, it wouldn’t be long before things changed.

Trump’s Election Changed My Company’s Politics

The rise of Donald Trump in 2016 polarized everything. It was no longer conservative versus liberal or Republican versus Democrat. His election was a rebuke of the entire political establishment. Most people believed the insanely dangerous media narrative that if you supported Donald J. Trump for President of America, you were a Nazi. This was no different inside a growing public company with shareholders. Most conservatives I worked with were very quiet prior to the election because of the vicious narratives that the media was driving everywhere. We had a very diverse company, and expressing yourself was encouraged. However, only the people who believed conservatives were Nazis were taken seriously. Any claims of harassment by co-workers based on political or religious grounds weren’t taken seriously because of the mainstream messaging on the nightly news. It was hard to watch.This is where things started to unravel. Under Trump’s presidency, our company grew exponentially. Rules and regulations were pulled back to allow us to go into different markets and hire new people. While this seemed like something the company would cheer, they did not. They took a clear political stance against the president and supported left-wing causes through donations. By this time, after winning numerous accolades, I was forced to change positions and commute an hour to work because I was called a white supremacist inside my office. On its face, this was absurd. I am a Lebanese, Native-American Christian. Obvious facts didn’t matter anymore, and the label stuck in this smear campaign.While keeping my job and my politics separate, the harassment never ended. I took a lower position in the company, which claimed its motto was "Be yourself," and I went on to receive even more awards over the next two years. I continued to have the most diverse and talented staff around, but the damage was done. I knew my time there was short, and I would never grow within the company. But then things got even worse.After becoming one of the largest players in the tech industry, our CEO openly adopted Marxist slogans about being the "revolution." There were TVs constantly letting you know that you were a part of this "revolution" on a loop in every office. The company was now taking large sums of money from far-left activist groups that consider Christians a "threat." We were taking political positions through internal memos that would reward us to participate in leftist activism. There were openly sexual ads being run at work. My outlook on this company changed very quickly. Despite how much they did for my life when I needed it, I could no longer support a company that openly attacked families, conservative reporting and education, yet promoted far-left activism.

But then things got even worse.

My Non-Compliance With Company Culture Ended My Tenure

For my family, I tried not to say a word about these new policies at work. While the company grew, our lives improved. However, it was not long before the ideology became real, and it affected my life. I started being ostracized from social gatherings, called out for not participating in social initiatives and was left out of internal conversations. I was being blackballed when I wasn’t even a vocal conservative. My co-workers knew I was a Christian, and they knew that I did not "hate" President Trump, but I never openly advocated for him or anyone else. That was not my job. My job was to hire, manage and make decisions that would grow the business. I never used my influence in the company to advocate for my religion or politics.In 2019, the company was about to make one of the largest mergers in American business history, and I was one of the people who helped get the company ready in my area. I was still receiving regular awards. However, this was no longer enough. People started paying attention when I didn’t spend my free time advocating leftist causes. I was constantly asked why I wouldn’t represent the company in protests or celebrations. The simple answer is that I worked a lot, and time with my family was precious. The other reason I didn’t go is that my morality doesn’t have a price. I can’t fake beliefs just for personal gain. This was my great sin.It wasn’t that I spoke up loudly; however, I was forced to defend my non-compliance. I didn’t come to work wearing Trump hats. I didn’t try to recruit people to church or spread the gospels. I simply wouldn’t comply with the new social direction of the company. Because of that, I was told that a news article from 2014, which had already been settled, may be damaging to the company merger despite it being public for my entire career. Suddenly, my past mattered to my boss despite years of producing nonstop without complaint. I didn’t lie my way into the company. Higher-ups were briefed on my legal status at all times. HR wouldn’t listen to any of my claims of harassment. They found those claims to be credible despite my family going through a nightmare of daily rumors.Finally, my boss sat me down. He handed me an award for being a top leader in the country and then asked me to leave my office immediately. The reason for my termination was never disclosed to me. It was considered a "no-cause" termination, where no harm was done, and they wouldn’t release my internal complaints back to me. No lawyer would take the case because they said that “being a Christian is not a protected class" in the state where I live.

I was being blackballed when I wasn’t even a vocal conservative.

Tech Companies Silencing Employees Is Dangerous

While this may sound horrific, this is what drives my journalism. Tech is now the most powerful industry in determining what voices get heard and what voices don't. I watched people be forced into silence. I watched people move around for their personal, political and religious beliefs internally. A culture of freedom ceased to exist; it was replaced by one of obedience. This is dangerous.If we don’t allow people to speak, understand each other and have an open dialogue, then this cycle will continue, and it won't be long before wrong-think is punishable under the law. If this sounds crazy, ask yourself what sounds worse: Going to jail for a few months, or never finding work again based on your ideas? The latter is truly dystopic to me, and tech companies are being disingenuous when they say they don’t have an agenda. My family found that out the hard way. We should all take an interest if we want to keep our civil liberties.

Psychedelic Therapy Is the Therapy of the Future

I take mushrooms once a month. It’s a ritual.My mom doesn’t get it. “You’re turning into your brother,” she says.Mom dropped acid in college. She’s open with us about it. During quarantine, I saw a photo of my parents at a wedding in the '70s, and I swear my dad was holding a little baggie of white pills in his hand. But today, they’re stringent and stuck up about drugs being a bad thing, as “good parents” are supposed to be.

Psychedelic Drugs Aren’t the Solution, But They’re Part of It

My brother and I both do advocacy work in the psychedelic field. It took me wading through 15 years of denial to figure out that psychedelics might have the answers that I wasn’t finding in yoga class. That Judeo-Christian whitewashed version of what they call “yoga” today isn’t the whole story. Those rishis back at the beginning were tripping balls.Interested in consciousness?Don’t get me wrong. Psychedelics won’t give you the map, but what they can do is let you zoom out and see the lay of the land so you can plot your course more wisely. If you aren’t awake in your normal life, then your experience will just feel like an amusement ride: get on, get high, get off.That’s not going to help society. In our collective dissolution and devolution as a species, we need something to guide us home. We’ve forgotten what it means to be human. Our idea of connection during COVID has become writing “I’m with you” in crayon and holding it up to our glass cage. We outsource the care of our elders and let them die alone. Have we really become so uncivil?What got us here?What allowed for us to disconnect from the elemental human right of exploring the alleys and pathways of consciousness? Is it not my mind? So shouldn’t I be able to do whatever the fuck I want in it?

I take mushrooms once a month. It’s a ritual.

Not All Substances That Get You High Are Bad For You

I am a product of my environment, and I must grow with it. Mushrooms grow everywhere for a reason. Go out into any old-growth forest and walk around and you might be rewarded with some amanitas. You know, the Smurf-like, red-capped, white-dotted mushroom seen in depictions from Christmas to gnome stories? Yeah, it’s been rife throughout history.What were you taught about drugs, anyway? That they were bad? Evil? For sinners? That you’d die if you take them? Or only the bad girls and boys are crazy enough to do them?Who made the curriculum about drugs in school? Were they talking about synthetic, addictive substances like meth and cocaine? Or was it an easy catchall strategy, dumping all substances into one bucket?America’s war on drugs gave birth to D.A.R.E., a horribly uninformed curriculum based around a harmful premise: “Drugs are bad. They kill people. Just say no.”Meanwhile, at the end of last century, the CIA may or may not have facilitated the massive cocaine trade from Colombia, destabilized multiple Latin American governments and let hard drugs into the U.S., all while filling jails with Black “marijuana felons.” Over the past 40 years, the prison population in the U.S. has grown 900 percent, mostly with Black and brown people.(Could you imagine if someone could get arrested for carrying another green plant down the street. Parsley maybe. Celery? No, make it sage!)

Prescribed Drugs Do More Damage Than Psychedelics

Anyway, we’re one leg out of the bucket, crawling away from a disaster in our wake. We’ve already wasted years of potential human evolution. Research was being done actively in the medical community back in the '50s by people like Humphry Osmond, who coined the term “psychedelic” (meaning “mind-manifesting”). Even back then they credited hallucinogens for their “ability to make patients view their condition from a fresh perspective.” Then, in the '60s, research went institutional at universities like Harvard by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass) and others. They understood that modern psychiatry had been toxified by old white men and the DSM. (Is that how we want to look at the psyche? As irreparable on its own? In need of “other” drugs to keep it “sane”?)From antidepressants to anti-anxiety medication, we’re all tripping today anyhow. Unfortunately, though, it’s all the knob-and-levers chemical stuff. All they do is increase your amounts of neurotransmitter secretion. They disempower your native happy/calm centers and artificially numb you to stimulus. We’re medicating ourselves into the walking dead.Well fuck, that’s a twist in the battle scene of the drug war. Those '60s hippies, liberating their minds, dropping out and tuning in, were too much of a threat to established corporate order. Thanks to stigmatization, LSD and other psychedelic drugs became highly regulated Schedule I drugs in the U.S. when the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1970. (In Southeast Asia, possession is punishable by death.)

Are you happy?

The Plan to Stop Hallucinogenic Therapy Probably Went Something Like This

These humans liberating their minds…How to keep them in line? The law. How to make money off of their desire to still feel good? Either fine them an arm and a leg if you find them with drugs…or set up an industry to make even more addictive synthetic drugs that create an abnormal “happy” state (but still one in which they can drive and think “rationally”). Yes.We will use the pharmaceutical industry to dose it out.Brilliant.Nearly a quarter of middle-aged women in the U.S. today take an antidepressant. That’s one in every four. Let that soak in.Are you happy?I am, normally. But like anyone else, I have my moments. Perhaps I even wear a veil of fear around. It creeps in more or less, depending upon who I’m with. Every time I take psilocybin, on a beach or on a hike, I remember that there’s no reason to be afraid. I get to watch myself from that “other” point of view. My belly distends a bit more with my breath and I relax.Can that be available to all humans soon?

Psilocybin Therapy is Only the Beginning

Fortunately, today we’re making headway. The second wave of the psychedelic renaissance is upon us. And we have many modern leaders to thank, picking up the work of the researchers from the '60s alongside shamans and our ancestors from the dawn of homo sapiens. Thanks to organizations like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), still at work 40 years strong, we are bringing consciousness into the limelight, along with the ability of the psyche, when lovingly explored, to heal itself.Current studies, all the way through to stage three of clinical trials approved by the FDA, show psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to be incredibly promising in reversing PTSD. The test study group? Veterans. Whereas the normal route of prescribing a pharmaceutical for PTSD has about a 23 percent success rate, the MAPS trials are showing psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to have a nearly 70 percent success rate. You just don’t see those kinds of numbers in normal experimental trials. We’re getting somewhere, even if, as usual, we have to rely on science to “prove” the obvious.Neuroimaging and DMT research is being done at Imperial College London by Robin Carhart-Harris, a generational leader. Psilocybin research at Johns Hopkins and NYU prove that mushrooms are, beyond a doubt, better antidepressants than the ones doctors prescribe—so much so that we don’t even need to keep taking them in order to keep healing.And in the psychedelic world, mushrooms are just an entry door. For those who need more of an underworld experience, there’s peyote, iboga (which I don't recommend) and of course ayahuasca (which people who aren’t native to the Amazon really shouldn’t be doing, due to their lack of cogni-ethnological priming). For those who might need more of a celestial experience, LSD, San Pedro cactus or even the synthetics MDMA or DMT might get you to see through eyes you didn’t know you had.We are remembering.

What Growing up Unvaccinated With Depression Was Like

The room was spinning. I closed my eyes. The floor swayed beneath my bed. My hands moved through the darkness to turn the dial of my five-disc stereo up, The Wall on repeat, and grab another handful of Goldfish from the bag. Then I lied back down. I hadn’t left my room for days and hadn’t eaten a meal for nearly as many. I’m sick, I told myself. Feed a cold, starve a fever, right? I willed myself asleep, with the thought that I’d wake up when I felt better. I was 14.My mother had discovered a new diet, the Schwarzbein Principle, similar to Atkins or keto, where anything protein-based and low-carb was king. Our fridge was loaded with local, organic, grass-fed beef and butter. It was supposed to help with digestive inflammation, give you more energy, boost your immune system—never mind the weight loss benefits. Her nurse practitioner said it could even improve her memory. My mother combined this dietary shift with a series of supplements prescribed by her cadre of holistic healers. There was krill oil for her heart and joints from her naturopath; collagen and probiotics for digestion from her nutritionist; St. John’s wort for seasonal depression from her counselor; vitamin K2 and elderflower for allergies from her D.O.; anti-aging herbal tinctures from her energy worker; milk thistle for liver function from her chiropractor; lutein for eyesight from some article she’d read. She took them by the cupful over breakfast, lunch and dinner.While she stocked the freezer with sides of local pork, I discovered old copies of PETA magazine in my library’s "Teen Corner." Years before the internet, I poured over printed pictures of bloody chickens and pigs crammed into cages. “I’m a vegetarian,” I declared as my mom stuck a London broil in the oven. “That’s horrible for your body and your mind,” she responded. “You’ll get tired and your muscles and brain won’t develop like they should.”

My Mother Was All in on Holistic Health

A holistic approach to health preaches the body-mind connection above all. In my mother’s world, there wasn’t any issue that couldn’t be resolved with nutrition and supplements. When I told her I was feeling sad, she said, “Try St. John’s wort and vitamin D.” When I told her they hurt my stomach, she said, “You don’t get enough protein.” If my siblings or I refused supplements, or the ailment persisted, it was time to seek another type of healer. My sorrow came in waves, but my little sister’s anxiety was intensifying. She described spells of disassociation and suicidal ideations. When the chiropractor couldn’t help, shamans were hired to retrieve her soul. Two gray-haired women with heavy New England accents showed up in a minivan, carrying sage, crystals and a drum stretched with deer hide. For an entire afternoon, my sister laid on the floor covered in a blanket while they beat the drum and called for her soul to return to its body. “Your soul is ancient,” they reported. “You have plenty of guides. They say you will never know yourself as well as they do—you’ll be fine. This lifetime is but a fraction in the limitless tapestry that is the universe. Your spirit animal is a mountain lion.” My sister was 13.

In my mother’s world, there wasn’t any issue that couldn’t be resolved with nutrition and supplements.

How My Mom Became an Anti-Vax Mom

My mother’s abandoning of traditional science was a decision developed over her lifetime. Just as my vegetarianism acted as a semblance of control and rebellion in an otherwise cultivated environment, my mother sought alternative healing in a deeply medical household. My grandmother was one of the first women to graduate from Cornell medical school, and my grandfather was the director of a famed New York hospital. My mother’s voice was lost in a household of science, swallowed by doctors that always knew better and never had the time. She was raised to believe that if there was a problem, a pill could cure it. Towards the end of her life, my grandmother took pills by the cupful over breakfast, lunch and dinner, for her arthritis, her digestion, her mental acuity—and for the side effects of the pills. She died chasing a cure for the Parkinson’s she battled, never fully accepting a life outside the diagnosis, nor the grown children waiting to be loved by their mother.My mother rebelled by moving west, a prototypical flower child of the '70s. She found acceptance in a community that stood against war, shunned the Man, preached that love conquers all and believed Mother Earth contained all the herbs and nutrients we needed to heal. For the first time in her life, she felt love and light. Eventually she returned east, got married and had three children. She swore she wouldn’t be like her parents. Believing traditional science was the ultimate evil, she packed our cupboards with herbs and refused to vaccinate her babies. But the paranoia didn’t stop with medicine. It grew into her views of the government and religion. We were not only homeschooled but unschooled—an education without curriculum or rules. In her mind, all she wanted was for us to be held in the same light she had found. She didn’t understand that stepping too far into that light can lead to a life in the shadows.

Turns Out, I Needed Professional Medical Help

Last year, the swirling started again. I lost my speech and couldn’t sleep at night, sobbing at random intervals throughout the day. I started questioning if life was worth it, if there ever was—or could ever be—any hope. I was back to the days of Goldfish and wanting nothing more than bed and sleep and an end to it all. This time, I sought a psychologist. “You’re having a major depressive episode,” she said. “I expect you’ve had these before.” Now in my early thirties, I thought back to my teen years. “Have you tried antidepressants?” I could feel my palms sweat and my stomach clench. No, but I’d tried St. John’s wort. I was taking vitamin D. I even saw an energy worker. “I can help you with talk therapy,” the therapist explained, weeks later, when I still wasn’t recovering. “But your brain is in a pit right now. The pit is so deep, it’s hard to get out of it alone. I’ve rarely seen people get out without help.” She searched to meet my eyes. “It doesn’t have to be forever, just for right now.”Okay, I thought. I’ll give this a shot. I found a psychiatrist, and he prescribed a low dose of Lexapro. “See how it makes you feel, and we can go from there,” he said. Slowly, I started sleeping through the night. I upped my dose and stopped crying during the day. I was getting better. I was healing. I kept seeing my therapist, and eventually, when speech became easy and hope returned, I started working with my pharmacist to wean off the drugs again. But I know they are there if the pit returns.

How to Talk to Anti-Vaxxers About Depression (Hint: Just Don’t)

I couldn’t tell my mother I was on antidepressants. I tried to broach the subject once over dinner, and her entire body shifted. “I just don’t feel antidepressants do any more than diet and meditation,” she snapped. “Big Pharma just wants us to believe that pumping our body full of cancer-causing chemicals is the only way to heal. Did you try any recipes from that Heal Your Gut book I sent you? Feelings of lethargy and sadness can be traced back to gut flora. And what about those guided meditations I forwarded from my spirit group? Each session is around an hour, but worth it. Sandy says she cured her insomnia.” I closed my eyes and let the topic drop.“The way it works,” my sister says when she recalls our upbringing, “is you feel so ashamed of these practices that you keep them a secret from the rest of the world. Like, ‘This is the truth and you’re wrong, but I can’t tell because I don’t want to be ridiculed for it.’ It’s incredibly lonely and isolating. The mainstream becomes the enemy. The only constant is doubt.”

What started as a movement toward acceptance shifted toward exclusivity and control—a dogmatic psychology that can guide its participants toward alienation and isolation in their eternal quest for health.

Understanding Anti-vaxxer Beliefs Has a Silver Lining

The other day, I watched as my mother counted out capsules that she’d spread across her kitchen table. “I’m adding red yeast rice supplements to the mix,” she explained. “My nurse practitioner says it will help lower my cholesterol. I don’t want to have to go on Lipitor.” She spits out the last word, like an evangelical housewife talking about the devil. “I’m also going to be extra strict with my keto this week—I’ve been so bad recently. No more fruit! No more treats! So if you see me saying no more often, don’t be surprised.”Even though I’m grown up, it’s still hard for me to untangle my mother’s world from my own. But I also see how much of her waking hours—not to mention her paycheck—are consumed by these alternative regimens. What started as a movement toward acceptance shifted toward exclusivity and control—a dogmatic psychology that can guide its participants toward alienation and isolation in their eternal quest for health. For me, I’m beginning to understand that the concept of “holistic health” only works if it is treated as just that: a practice exploring alternative perspectives and modalities working together as a whole. In that way I can finally accept the gifts she gave me: I will not be scared to question the norm. I will advocate for myself and demand more from the mainstream medical community. But I will also know my limitations and allow medicine to step in and take over when I’m down in that pit.

Community Management Is a Shareholder Capitalism Cover-Up

When First Round Capital tweeted that “Community is the new moat,” I felt the first pang of anxiety that my work in community was finished. That coffin was sealed with the announcement of the Community Fund, a venture capital firm with the investment plan of making community-driven companies into unicorns. For the past decade, my peers and I have consulted and built businesses around community building, the business function that cares for and engages customers with each other. Even a few years ago, we still found ourselves having to explain the difference between a community manager and a social media manager, but since then our little industry has become more noticeable. We’ve built superuser programs, online engagement strategies for presidential candidates and revenue-generating programs that fundamentally changed companies’ relationships with their customers. Work was plentiful and budgets (with larger companies, brands and national nonprofits, at least) were sufficient, if not generous.

We’re finally seeing technology for the weapon that it can be.

Professional Community Management Is Dying

In 2020, community is hotter than ever. On Twitter, at least. Along with words like “belonging” and “engagement,” “community” is the new must-have checkbox that every growing company needs to fill. The hype only escalated further in wake of COVID-19, as online communities replaced in-real-life connections, and executives became reliant on their more tech-savvy, more junior community counterparts to transform conference experiences into Zoom rooms. In reality, community managing has tanked this year. Every community consultant I know is struggling. Our in-house counterparts are desperately trying to hold onto their jobs, if they haven’t already been laid off. I used to get client inquiries for complex, monthslong $150,000 projects. Now they’re for $15,000. Sometimes they’re $1,500. Another shift has occurred recently: We’ve lost faith in our technology. Facebook is under fire at the White House. Media darling companies are being called out left and right for racist behavior within their company policies and tokenization in their marketing. Tech employees are unionizing and staging walkouts. We’re finally seeing technology for the weapon that it can be.

My Experience as an Online Community Manager

Today, I see community as the showmanship of a technology culture that’s desperate to appear benevolent in a tide that is turning against it. Tech startups mask their fear of customer revolt—the power that consumers online have always had since the conception of social media but only fully realized in this boiling, polarized political environment—by using community. All it takes is one too-true tweet or Instagram story for the wrath of the internet to destroy carefully crafted brand reputations, customer trust and loyalty. Instead, in a game of attempted offense, companies build ambassador programs and host Slack groups in hopes of winning favor and using the positive momentum (for now) to further their growth. With the wrapper of “community,” companies can claim that they were trying to do right by their customers. Truthfully, many of the companies I speak with about working together do want to do right by their customers. They genuinely want to build a community. But startup folklore robs them of knowing what community takes: a deep understanding of their customer needs, a willingness to address those needs, the patience to develop deep relationships, elbow grease, muscle and a lot of time. Community won’t just appear on a platform that they buy or a Facebook group that they launch. Further, the desire to build a community is in conflict with the very system in which their company exists: shareholder capitalism. Venture capitalists and shareholders are prioritized over customers and community members. Growth and scale are prioritized at all costs to maximize financial returns. There is little left over to build a community.

Venture capitalists and shareholders are prioritized over community members.

Community Management and Capitalism Cannot Coexist

When VCs say that community is the new competitive advantage, or that it will lead to a $1 billion valuation (both of which benefit the company, shareholders and investors much more so than customers and community members), founders and executives are forced into community commodification. What investors like the Community Fund have overlooked is that building a community and building a unicorn are fundamentally at odds. A community-striving company that turns into a unicorn is a lucky outcome, though a unicorn-striving startup will likely never have a community. Growth at all costs is in direct conflict with what a community needs.

Educational Technology Is Important and COVID Proves It

When I was a classroom teacher, I was set up to fail. I didn’t know this when I arrived at my Los Angeles middle school ready to change the world. But once I realized how distinct each of my hundred students was, I saw the futility of my instructional efforts.Some kids only spoke Spanish, Thai or Wolof. Most read below grade-level expectations. Several had severe learning disabilities. How could I possibly reach each student’s needs during a 90-minute period with 35 learners?Alone, I couldn’t. With technology’s assistance, I could have. This is why the coronavirus might be the catalyst we need to improve learning outcomes. As this pandemic closes schools and pushes them to online learning, educators are poised to embrace the power of personalized instruction that only technology can provide.

As problematic as coronavirus-caused school closures are, they’re offering a valuable reset moment for education.

The Benefits of Technology in Education

Despite the fact that we continue to rely on it, group teaching's efficacy is limited. You may remember being a bored student who had to sit through your teachers’ explanations of concepts you had already mastered. Or perhaps your classes went too fast, and as a result, there are still gaps in your knowledge today. Technology solves these problems. Adaptive products can adjust practice and teaching based on a student’s level. Machine learning can score and correct kids’ work to give them immediate feedback. Browser extensions can read texts aloud and translate them, while analytics can track performance and progress. These resources only help, however, if educators are willing and able to use them. As problematic as coronavirus-caused school closures are, they’re offering a valuable reset moment for education. We’re being forced to reconsider how technology can support learning—and to give it a chance to do so.After I stopped teaching, I became an educational software trainer, instructing teachers on using the new products that their districts purchased. I rarely got a warm welcome. When I first saw the adaptive test tool, which I would train teachers to use, I was shocked by its power. It would have saved me hundreds of hours and made my teaching time more meaningful. I couldn’t understand why so many of the educators I was teaching were disinterested in it.

Teachers do great work, but their positive impacts are limited by the resources in place to bolster their efforts.

Why Teachers Are Apprehensive About the Use of Technology in Education

I now know there are many good reasons that teachers resist new education technology. In some cases, they’re told they have to use something that they haven’t vetted or bought into. They’re also often overwhelmed with all the material they’re supposed to be cramming into each class. It might feel like there’s no time to master a new tool, even if it promises to save time in the long run. In addition, veteran teachers who have been in the classroom for decades may be uncomfortable with unfamiliar technology, and teachers of all ages have the very human instinct to resist change. They’re used to teaching a certain way and think, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The problem is, for many students, “it”—the way we expect kids to learn—isn’t working. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), only about one-third of eighth-graders reach reading proficiency. The numbers aren’t much better in high school, and math performance is equally abysmal—NAEP reports that just 34 percent of eighth-graders reach proficiency in this subject. Literacy and mathematics, the foundations of education, are in need of a fresh approach. It’s not that teachers aren’t doing a good job. My middle school colleagues worked harder than those I’ve encountered at investment banks and tech startups. But the bankers and executives have the tools they need to be successful. There are time and money to implement the best technology to support them. Teachers do great work, but their positive impacts are limited by the resources in place to bolster their efforts.

Teachers Are Just as Important to Education as Technology

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, educators have relied on educational technology tools to run their classrooms. When I was teaching, I used an online system to take attendance. This saved time and cut paperwork. But it probably didn’t impact learning. Research from the Brookings Institute confirms that adding technology doesn’t ensure learning or student growth. Digital programs have to meet the challenge before them. Just putting old-school worksheets into a shiny new online format cuts grading time but changes little else.Educators are aware of the distinction between online worksheets and high-quality digital instructional tools. But they may not have felt an urgency to regularly implement the latter until schools began shutting down. At the ed-tech company where I currently work, teachers from closed schools around the globe are reaching out for help. They don’t want a digital stand-in for worksheets. They’re asking for a digital stand-in for themselves. I recently heard a venture capitalist discussing the future of education. He presented a few possible scenarios, noting that he favored the one in which tech fully replaces teachers. This setup would leave students undersocialized and lonely, to say the least. After years in the classroom and building ed-tech, I see the power and limitations of on- and offline learning. Education’s ideal future embodies both. The current distance-learning trend may mean that this future will be here soon. It’s about time. As President Lyndon B. Johnson proclaimed more than half a century ago, “If we can use our technology of electronics to defend freedom and keep peace, we can apply this great technology to open new horizons for young people.”

What Not to Talk About on a First Date? Definitely Gravity

When I was younger, I was terrible at dating. Or at least, I felt like I was terrible at dating. Maybe it was just subjective social anxiety, and the women in question were not in fact as bored and irritated as they seemed from where I stood. But I do have at least some objective evidence that it wasn't all in my head. I ruined one date by talking about gravity.It didn’t seem like a topic to avoid on a date. I had just finished a master's thesis focused on the history and philosophy of science, and I was fairly excited about it in a nerdy and arguably overbearing way. So when I was set up with Georgia by a mutual friend, and she politely asked me about what I was doing with my life, I started babbling about science and religion and how the two were more similar than you might expect. I may have name-dropped philosopher Paul Feyerabend, whose 1975 classic of contrarian cosmological provocation, Against Method, argues that Galileo didn't really prove the earth went round the sun.

I ruined one date by talking about gravity.

How I Discovered Gravity Is Something You Shouldn't Talk About on a First Date

Galileo was the only one who could make sense of what he saw through his telescope. Others who weren’t trained by him didn't see clear evidence that his theories were correct. If you were the only one to see gremlins pushing up the sun via your patented gremlin detector, we wouldn't consider that scientific evidence for the existence of gremlins. And Galileo's calculations for planetary motion in a heliocentric universe weren't clearly less complicated than the calculations for a geocentric one. Galileo's vision of the universe wasn't demonstrably better than what people were using at the time. Feyerabend argued that the church's skepticism in support of the contemporary scientific consensus was warranted.People used to have faith that God made the sun come up. Today people have faith that the earth goes around the sun. It seems like those beliefs are different in kind, but for most people who aren't experts in theology or physics, they work much the same. You're just trusting people in authority to tell you how the universe turns around you, so you can get on with your own, less-cosmic concerns. And those authorities, like Galileo, can be dicier than you might think. Take gravity for example…Georgia stopped me there. "But people know how gravity works," she said. "That's different than just saying God makes the sun come up.""Actually they don't know how gravity works," I replied. "Nobody's really sure. There are theories but…""Sure they do," she said. "Gravity is caused by the spinning of the earth, right?"I did a double take. The world moved under my feet, but not in a good, sexy kind of way."No it's not!" I shouted. "The earth spinning doesn't have anything to do with gravity!"There was a brief pause, in which I had time to notice again that she was very pretty as the spinning earth slowed, stopped and then gracefully opened on an abyss."I don't want to talk about this any more," she said.And so, like many a blowhard academic before me, I won the argument, and lost the date.

The relationship between fact and theory is more tenuous than we tend to think.

In Some Ways, Science and Religion Are the Same

You could certainly argue that, in this case, the date splattering on the sidewalk like a Newtonian apple dropped from above wasn't necessarily my fault. You could blame it instead on an inadequate educational system that had left Georgia somehow believing that apples would fall upward if the earth started spinning in the opposite direction, just like in the Christopher Reeves Superman movie, where he reverses time by flying around the earth really fast and getting it to rotate backward on its axis. (Kids: Don't try this at home. Reversing the rotation of the earth will not bring Lois Lane back to life. Nor will it allow you to rewind your conversational faux pas and talk about something other than gravity. Like the weather. Or bunnies. Or anything, really.)In defense of secondary school physics teachers, though, the point I was trying to make overzealously to Georgia was precisely that ignorance and the indifferent assimilation of scientific knowledge by the polity has, like the apple, theoretical weight. We think of science as this set of facts that exist out there, in the universe, regardless of our personal feelings. You don't have to believe in gravity, but you assent to it every time you don't step off a building. Gravity is waiting, inescapable. It could be the spinning of the earth. (It's not!) It could be caused by the actions of quantum particles, though scientists haven't been able to confirm that at all. It might be a result of the curvature of space, though again, no one's really proved it. But it's there, even if you don't know what it is—even if no one knows what it is.Or is it? After all, refusing to step off a building doesn't tell us anything about the truth or universality of gravity. The reason we don't step off buildings is that we've seen what happens when you drop that apple. We have an ad hoc, experiential understanding that falling is painful and to be avoided. But that's consistent with any number of theories. We talk about gravity, but you could also say, God just made it that way. Or you could say the earth spinning pushes us down on the surface. Refusing to throw oneself to one's death doesn't prove gravity exists any more than the sun coming up proves God cares about us.

Science Can Also Be Subjective

The relationship between fact and theory is more tenuous than we tend to think. For most of us, most of the time, when we rely on science, we're relying on scientists the way people used to rely on priests. Gravity, like other scientific knowledge, is a doctrine handed down to us by authority, not a truth we verify for ourselves. And in this case, when you ask for final causes, the authorities are blundering around in a dark universe with the rest of us. "Invisible gremlins are keeping our feet on the ground," is just about as good an explanation as anything scientists have got.Of course, science can be an incredibly powerful engine for turning out claims, predictions and blueprints. Thanks to a very fine-grained understanding of how gravity works in practice, we can put a spaceship on the moon, barring the occasional tragic explosion. You can often shoot straight in practice, even if your theories wobble.And if the wobbling theories don't cause us to fall into space, why make a fuss about them? Feyerabend famously argued that in science, "anything goes." He didn't see science as a rigorous process in which you create a theory as a foundation and then build facts from there. For Feyerabend, science was an exercise in floating from theory to theory, using whichever one worked best for the moment. If "the rotation of the earth causes gravity" is good enough to get you through the day without blowing up in a rocket ship or falling from a height, it's good enough for Feyerabend. Maybe at some point that weird, errant, heterodox idea will even come in useful, as Galileo's did, despite the fact that it didn't quite work as science in its own day, in theory.

Perhaps Science, in General, Is a Topic to Avoid on a First Date

I didn't explain all of this to Georgia because she asked me not to, and I'm not a complete bore in every respect. Nor will I ever. I haven't spoken to her or heard about her or even thought of her in decades, save as a character in this anecdote, which I trot out every so often as a joke on myself, or the universe, or some combination thereof. I don't even recall her name, though I'm pretty sure it wasn't Georgia. Nonetheless, I presume she's still out there somewhere on the earth we'd both agree is still spinning. She's a somewhat painful memory, even now, though also a precious one. Connection is valuable, and it's what you're looking for on a date, in general. But there's some magic too in being reminded that we're not all tethered to the same ground by the same force, or any force. Every so often it's good to let gravity go, and drift up like Newton floating into the tree, even (or especially?) if from way up there in the clouds you look like kind of a jerk.

The Metamorphosis: How the Internet Helped Transform My Brother Into a White Supremacist

“When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin." Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis is about a young salesman who finds he’s been transformed overnight into a giant insect, or “monstrous vermin,” to translate the German word “Ungeziefer.” Throughout the novel, Gregor hides in his room, afraid of terrifying those closest to him. Though he grows to enjoy his new body, scurrying up walls and along ceilings, he soon overhears his family discussing its financial troubles. Grete, his sister, is supposed to go to a music conservatory, but Gregor’s burdensome form prevents her from attending, and she resents caring for him. At one point, Gregor’s father wishes his son would leave so the family could avoid ruin. Eventually, in the darkness of his room, Gregor eventually dies. It’s a heartbreaking story. Kafka never explains why poor Gregor turns into a cockroach-like pest, but it’s been on my mind over the years as I’ve watched my own brother, my former best friend, become someone unrecognizable. In the span of three years, he’d transformed into his own kind of scary creature: a misogynistic, white supremacist.

My Brother Always Used to Include Me

Two years ago, at my master’s commencement ceremony, our speaker asked us to applaud everyone who helped us on our journey. He gave a shout out to his brother, who “always provided needed comic relief.” I turned and smiled at my spouse and parents, and they beamed at me from their seats. My own brother, however, wasn’t there.Twelve years ago, he attended my high school graduation. There’s a picture of us from that day making identical goofy faces. Eight years ago, he attended my college graduation. There’s a similar picture of us from that day—he’s in a suit and I’m in my graduation regalia, and we’re both grinning from ear to ear.But in 2018, I didn’t invite him to see me graduate a third time. I didn’t want him there. I didn’t want anybody there who believes that women are “weak, cowardly and stupid,” or that sexual assault is the victim’s fault. I didn’t want anybody there who once said, “Radicalism is only bad if it isn’t true.”Are you sitting there wondering how my brother went from being my funny and compassionate best friend to being that guy? Yeah, me too.He was the best big brother when we were younger. He never picked on me or hurt me on purpose. He included me when his friends came over to play. Together, we played “explorers” in a nearby creek, searching for mythical creatures. He walked me home from school and we battled on the N64 in MarioKart and Super Smash Bros. His great reputation paved the way for me throughout school, as teachers knew me as the younger sibling of a star student. In high school, I was a lucky freshman because my big brother drove me to school every day in our ancient Toyota Tacoma. He was always a little socially awkward, but he used to have friends who shared his quirky interests. It was hard when he went to college halfway across the country, but we kept up with regular hours-long phone calls. I don’t know if something happened during those years—if some event in college, which he never revealed, influenced his later adult years. Maybe I’m just trying to rationalize irrationality. But I’ve looked back to see what went wrong.

I Realized I Lost Him

At first, it was his growing social discomfort that worried me. When we went on family vacations as adults, my brother brought his desktop computer and spent all his time in his room, door shut. On holidays, he started to avoid talking to relatives—a huge change from when we were younger. His metamorphosis was in progress at least three years ago. At a party one summer, my friend asked about his life, and he said he was examining different views. I acknowledged this was good, as many people live in echo chambers. But he failed to mention that he was learning opinions from Red Pill Reddit, men’s rights activist sites and YouTube, adopting the opinion that feminists, immigrants and single moms were causing the downfall of Western society, which, in his view, is the apex of humanity. According to him, our culture is doomed to be changed by others. He sees immigration patterns across the globe as threatening and thinks Canada’s humanitarian approach to immigration is a “canary in a coal mine,” exposing America going down the wrong road. He focuses on Muslim individuals who commit violent crime in the U.K. But he says he’s not racist. No, racism, he believes, is when the left oppresses those with different opinions. He conflates the consequences of repulsive behavior with oppression. Anytime someone is outed as a white supremacist and an employer cuts ties with that person, my brother cries, “Oppression!” Then, the Aziz Ansari story broke. In response to an op-ed sympathizing with the victim, my brother emailed dozens of YouTube videos railing against Islam and immigrants, with a diatribe about how weak and cowardly women are. He said if we want to “exist in the world of men, we’re going to have to earn things like men.” Respect must be earned, he said.I won’t detail how wrong he is. I’ve argued with him extensively and described what it’s like living as a victim of sexual assault, and the exhausting survival skills I’ve honed. I’ve explained how what I want is to be seen as a person first, to thrive in my own body, capacity and truth of who I am, and that it shouldn’t be contingent on anyone else. I asked if he’s ever met a Muslim person. When he didn’t have prepared talking points, he just sat and shook with rage. When I once expressed that I’d have an abortion under certain circumstances, he screamed that I was selfish for putting my life first. When I started a sentence with “Speaking as an actual pregnant person," he screamed: “I don’t give a fuck what the pregnant person says!” He continued shouting until my spouse suggested that if he had to choose between a life-threatening pregnancy and me, he’d choose me every time. This apparently never occurred to my brother, who said, “Oh,” and fell silent. At that moment, I realized how little I meant as a human to him. My life, dreams, health, family, decision-making—these were all less important than a hypothetical fetus, and my husband’s wishes. That day, I realized I’d lost him for good. I cried for a long time, and then spent years being angry and hurt. I’ve cycled through trying to help him, then being angry with myself for wasting my time.

I’m Not Sure if I Should Keep Trying

He and I were raised to respect each other’s opinions. Both my liberal parents come from politically mixed families that believed a political disagreement meant agreeing on a problem, not a solution.But this is different. There are those, like me, who think every human is worthy of dignity and respect, and then others, like my brother, who think white men are inherently better than everyone else, and that rights must be violently taken because that’s how men, and therefore the world, work (disclaimer: not true). How do you talk to someone who thinks only he understands the “truth?” How can I keep company with someone who thinks I’m inherently deserving of predation and disrespect, and that I am less intelligent, important and capable? There aren’t resources on what to do when your sibling’s been brainwashed by the alt-right. I want to have a normal conversation with him, but he only talks about his vile ideas. How do I balance the belief that I would never want my sibling to give up on me, with the desire to cut him off completely? How did Grete Samsa feel? Frustration, then shame at being frustrated? Hopeful and angry? I recently realized I’ve experienced a traumatic response in his presence. I’m tired of hurting, and seeing my parents hurt. They’re close to retirement and will probably spend the rest of their lives worrying about their son. Maybe you know someone like this. I’m sorry. You probably wonder what the hell happened. Maybe you’re angry, disgusted and heartbroken. I’m sorry you’ve lost that person, and that you try and catch glimpses of them in their rage-filled shell.We can’t change others, only ourselves. What’s not clear is how I should change in response to his metamorphosis. There aren’t guidelines or studies for this, just hurt and confused people who miss the person they once knew. If you figure it out, please share with the class. Honestly, I’d prefer a giant but amiable cockroach.

Tech Needs to Be More Inclusive. Now.

The world of tech has always felt truly and completely inaccessible to me. As a part of Generation Z, I am seen as all-knowing for simply being able to fix the Wi-Fi. I enjoy the artistic pursuits of things like Adobe Premiere and Photoshop for my personal fascinations and fancies regarding film and photography, but that is about as far as it goes. Not to toot my own horn, but I am a rather intelligent person and could do quite well if I tried, but it is the trying that gets me stuck. This is not to say that I am lazy, but that the idea of a constant barrage of capitalist and patriarchal values inherent to the nature of tech’s entrepreneurial spirit is quite tiring.Personally, I am a queer person and I identify rather heavily with my experiences as a woman. Both of these aspects of identity showed me how engrained inequality is in our "society" from a very young age. There are plenty of narratives as to why programs like Girls Who Code are important, giving oppressed groups a safe space for innovation, but that world simply did not interest me; possibly, as a result of the aforementioned notion that it would be an uphill battle for my entire career, working however many times as hard and being however many times as good to be valued at a fraction of a male counterpart.With that said, I have a deep respect for the BIPOC, the women, the LBGTQ+ and generally prosecuted persons who are intent to break down barriers—that they are willing to go through what I am not. As I learn more about the systems in place to destroy our will and enforce the current hierarchy, the more evident it becomes that every single aspect of industry in the West is insidious and that it's much more important to fight intersectionality for equality. Pushing my interests aside, I pursued a few courses at my university to have conversations and broaden the width of my knowledge. I am not naive enough to pretend that I will do anything groundbreaking, but if nothing else, my solidarity and advocacy will hopefully be of some use, as we are nothing if we do not use the platforms we have to help others. Considering I do not have much personal experience in the field other than my own readings and research, those are the factual accounts to which I will be referring to.If the average American compares the most well-known faces of technology, like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, the late Steve Jobs and the target market for the products they invented, they wouldn’t see much difference–all of them are white men. Gatekeeping at the entry level of the tech industry is keeping it from growing to its fullest potential. The erasure of BIPOC as consumers is making the race for innovation unsustainable.This gatekeeping is an inherent aspect at every level of tech. The lack of diversity at the very top of the hierarchy among tech monoliths is reflected in their consumer base as well. This isn’t to say that there are no minority groups represented somewhere out there, but they have to hop a multitude of barriers to even become a base-level consumer. New and hyped releases (or “drops”) for new, smart technologies are often quite limited and overpriced. If you follow the major production supply chains, it’s quite clear that they’re charging more than it costs just to pay creators fairly. It’s safe to presume that this is clearly a matter of creating an idea of luxury. With this act alone, the threshold for purchase grows even higher.

The lack of diversity at the very top of the hierarchy among tech monoliths is reflected in their consumer base as well.

The Internet of Things Will Create More Inequality

Now, it is important to acknowledge why the growth of the Internet of Things (IoT) can be beneficial to the average buyer. In basic terms, it allows for greater efficiency in everyday life, freeing up time for the user that they would have otherwise spent vacuuming or picking up groceries. They could pursue money-making ventures, or just use the surplus to take better care of themself, which is nothing to sneeze at. A main issue is that the average buyer is a white male, the person who statistically already has the most amount of time afforded to them. Buying into new tech grants them even more access to this asset. The old adage “time is money” readily applies. BIPOC communities have been faced with hundreds of years of oppression. Now that a new industry is taking off, they’re once again being left in the dust. In a society where minority groups still have to prioritize necessities like food and clothes, the most privileged group in the country gains yet another foothold in a blossoming field of work.

Getting a Job in Tech Means Getting Past the Gatekeepers

It’s not that BIPOC aren’t interested in technology, or that they don’t prioritize it. You just cannot be passionate about something you aren’t exposed to. If a person isn’t afforded access to high-end fashion, then of course they are not going to be interested in something as niche as say a vintage Maison Margiela tabi boot or the influence of Calvin Klein as a powerhouse in the 90s. To understand this dynamic even further, we could look towards the creation of groups surrounding Women in STEM, where there is clear prejudice to this day. What has for a considerable period of time been considered a man’s field is being forced open by ladies that have had to fight against systemic gatekeeping their entire lives. “Coding for girls” groups are still openly mocked. To this day I have never heard a single one of my engineering friends say that they feel heard among their male peers. There’s even a TikTok trend where women record themselves trying to speak in lectures, only to be repeatedly cut off by men. Smart technology is becoming another driver of the current resource gap in the United States. Think about the millions of people being cut off from having those extra hours in a day. That could be spent breaking boundaries, using their experiences to manufacture new ideas and widening the vision of an otherwise very narrow-minded industry. By having more access to technology, BIPOC would have more tools to bring them closer to equity.

It’s not that BIPOC aren’t interested in technology, or that they don’t prioritize it.

Automation Is The Next Barrier to Equality

Tech will continue to grow, and it will continue to disenfranchise minorities if certain infrastructure changes are not put into place—not only for advertising products, but to give people work. During his presidential run, Andrew Yang spoke a great deal about the effects automation will have on unemployment. The IoT will give people more time to pursue their interests, but the automation of those daily tasks is the negative side to that same coin. Once again, it all boils down to demographics. Automation won’t take over all jobs, but those that are eliminated will likely be the same people who are locked out of getting personal smart tech of their own. Once again, it will further the divide not just between what people have, but also what work people can do (or even have available to them). Going forward, as the job market continues to shift, it will be important to increase regulations to control the negative effects of automation, as well as treat the root of the issue in the industry, which is gatekeeping.

Science and Tech Helped Diagnose Me With Autism, After Years of Speculation

As a Gen-Zer, or “digital native,” my entire life has been influenced by technology. My parents pounded out essays on typewriters in high school while I was touch-typing on computers before sixth grade. All this technology provided support in some areas, but it also helped me conceal my struggles. Even with the world at my fingertips, I couldn’t find the words to express my greatest need. It’s surprising to think that my crutch would become my sword and shield and reveal my true self.

Autism Misdiagnosed as ADHD Happens Frequently

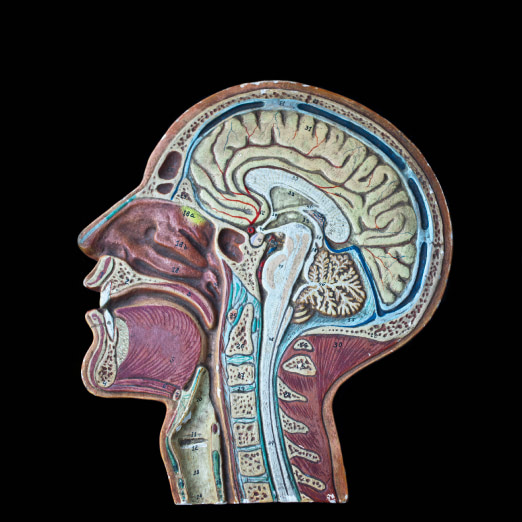

Before I get ahead of myself, let me tell you my secret struggle. I have high-functioning autism, but I was previously misdiagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). My situation is all-too-common. Women with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), known as Aspienwomen, mask their symptoms at higher rates than males to meet their gender’s societal demands. We are trained to look for what’s “normal” and to do what’s expected at an early age. It’s especially common to misdiagnose women as having ADHD, anxiety or depression, since many of the symptoms overlap with ASD.It took 22 years, a move to Alabama, and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) brain imaging to communicate what I could not. What exactly is SPECT brain imaging? I was injected with a nuclear tracer that my brain absorbed in proportion to blood flow. A gamma camera circled my skull while mapping cerebral blood flow. Computers stitched these scans together to form a 3-D image of what parts of my brain were functioning and where there were literally holes in my mind. Two days of lying on a table while gamma rays pierced my skull finally allowed my mind to communicate directly to the world. Why did it take radioactive tracers and computer imaging to speak for me?Growing up, it wasn't okay to have mental disorders, but I discovered some were worse than others. It was one thing to be ADHD, but heaven forbid I was atypical, much less full-on autistic. I honestly thought it was better to pretend everything was normal than to try to get a proper diagnosis. I was so terrified of being labeled ASD, I didn’t know where to turn. I couldn’t understand that it was okay for there to be something wrong with me and to seek help. My fear of the isolation ASD often brings even triggered my severe depression and anxiety.

Being on the Spectrum in High School Was Not an Option