Racism in Theater is Real: My Journey as a Black Actor|A Young, Black Ballerina and Performance Artist|A Young, Black Actor Sits in a Theater and Reads a Page From a Script|Billboards Advertising Plays in Broadway Theaters|A Young, Black Actor Sitting in a Theater Crying

Racism in Theater is Real: My Journey as a Black Actor|A Young, Black Ballerina and Performance Artist|A Young, Black Actor Sits in a Theater and Reads a Page From a Script|Billboards Advertising Plays in Broadway Theaters|A Young, Black Actor Sitting in a Theater Crying

Racism in Theater Is Real: My Journey as a Black Actor

Did you ever know you were meant to do something? Could be anything. As small as getting out of bed in the morning or as monumental as changing the world. It wasn’t hard for me to know. I’m 100 percent meant to be a performer. I have known it to be my destiny since childhood. My parents knew it, my teachers and friends, even strangers. It was never a crazy idea or a far-fetched dream. It is where my natural “God-given” talents lied. Consequently, I have been training for this career my whole life. My two parents, working full-time corporate jobs in Manhattan, made for a heavily scheduled childhood. I was never forced to do things that didn’t explicitly interest me, however. I trained in dance, piano, musical theater and sang in the choir at our church.Noticing I had an aptitude for entertainment, and that I quite enjoyed all of my extracurriculars, my mom and dad were always supportive, lending a late-night hand to practice dissonant, complex Bartok pieces with me or sit on the couch to watch whatever choreography I had learned in class that day. They, art lovers themselves, took me to the theater, to museums and the ballet. As Caribbean immigrants, they also had an expectation of ambition and dedication to excellence—something I inherited. They encouraged my every whim without indulging or coddling me through how hard it could be to hone these crafts.I am incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunities my parents worked so tirelessly to provide me. When I was about seven, I looked at my mother and said, “Mom, I’m going to be the first forensic scientist on Broadway! I’ll solve crimes in the day and make it back in time for ‘places’ in the evening!” I even went as far as landing representation and missing a lot of sixth- and seventh-grade classes to rush into the city for big auditions. Eventually, I decided I would finish school and wait to go full throttle into performing. Mom and dad agreed with my choice heartily, telling me I could be whatever I wanted to be if I put my mind to it. What they left out, knowing I’d ultimately discover it on my own, was that being Black would create unspeakable obstacles to said dreams—that no matter how good I got or how much talent I held, there would be invisible and tangible barriers that I couldn’t will or discipline away.

I Was Surrounded by White People All the Way Through College

Growing up, I spent plenty of time in predominantly white spaces. I was one of roughly five non-white students at my elementary school and, for a majority of the time, the only Black girl in my myriad of extracurriculars. Though I went to a much more integrated, inclusive high school, the “others” (students of color, international students, Black and African-American students) stuck together, for the most part.I continued my performance studies in high school, taking as many stage-related electives as possible, while juggling the regular course load. When it came time for college, I was elated. After briefly flirting with the idea of going straight into acting professionally, skipping out on getting a degree, I bargained with my folks and settled on applying to 12—yes, 12—prestigious drama schools. Soon, I received a scholarship to one of the best drama programs in the world. Ecstatic, I spent the summer fantasizing about all of the newness ahead. I was going to get to really make a go of it and would leave not only talented but qualified to do the job, having earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from a renowned university.My first week I called my parents to thank them for everything that had led up to this moment. Life was peachy. And so what that most of my teachers were white? Or that I was once again one of fewer than five Black students? Or that during the first year, both in theory and in practice, we focused almost entirely on white, male European or American playwrights? I had arrived!

What Being a Black Actor Is Really Like

During my first two years of training, I worked retail part-time, which was grueling and barely sustainable. I remember failing a freshman class called “alignment” not because I didn’t do the work but because I had been late more than three times. It was at 8 a.m. every Friday morning and I was at the store until after midnight every Thursday. My advisor, who was also a script analysis teacher, patronizingly asked me if it was “absolutely necessary” that I work. She proceeded to ask me about how I was paying for tuition; she was curious as to the literal amount of my scholarship. I, not thinking, told her freely and proudly. “Wow, they must’ve wanted you bad!” she responded. “Makes sense.” Off the bat, I took it as a compliment. As I mulled it over in the coming days, weeks, months and years I realized how deeply inappropriate that entire exchange was. As training progressed, things got weirder and more charged. I remember a second-year professor comparing me to Viola Davis every chance he got, advising me one day after class that “when you stop being so angry, you’ll start to work.” I cringe at these memories now, especially thinking about the amount of times the other Black girl in my year got called my name and vice versa, despite looking nothing alike (she was a whole head taller than me). Or how I felt bringing in Black playwrights. Or having to coach white kids how to say the N-word. Or what it was like to teach the instructor about certain pieces, because they’d only read heavy-hitters in African-American theatre, like the great August Wilson. It was ridiculous how tokenized the few Black actors in my year were.

One Story Is Particularly Memorable

A particular moment that stings a whole decade later takes the cake for me, though. I was doing a scene from Lynn Nottage’s Intimate Apparel in a performance technique class. My scene partner was a white girl in my group, who was also a dear friend; we’d prepared the very vulnerable scene carefully and rehearsal was filled with honest conversations about race in the U.S. at the start of the 20th century, the setting of the play. We did our version for the class and then it came time for notes. It went well! Then the teacher took a second and turned to me. “My only note for you would be to bring specificity to the physicality of this woman. She’s African-American in 1905. You know, maybe explore holding your purse in front of you?” My stomach dropped. “Stick your butt out a bit?” she suggested. She sat back expectantly, waiting on me to do it. I obliged, loathe to challenge her, proceeding with the second round of the scene. It was utterly humiliating.

Art schools are actively failing non-white students. We need teachers that look like us and we need to learn about the artists that look like us.

Black Actors Are Being Set Up to Fail

My experience in drama training was mild compared to many of the Black actors in programs similar to mine. I finished school, passing with flying colors and winning a drama department award that gave me the chance to study abroad at another reputable school in the U.K. I went on to book an off-Broadway show a week before I graduated, joined the union and got a head start. But even then, the fragility of my connections with the white faculty began to rear its head once again. Those who couldn’t handle my Blackness in class were now my bridge between the training incubator and the industry. Many of my trainers were working actors, directors, playwrights, producers, etc. They were ill-equipped to help me ride the momentum of my first big job and could only feign interest in anything less than overnight success and the clout that would bring to my alma mater. This was demoralizing and I am still working to reignite some of the passion these instances extinguished. I could talk about this for hours and write more pages. But I’ve distilled the whole experience down to a couple of key points. First, I don’t regret going to school. I’m a trained actor and that means the world to me. Second, art schools are actively failing non-white students. We need teachers that look like us and we need to learn about the artists that look like us (not only the legendary few we learn about during Black History Month). We need post-grad resources that connect us with our communities within the industry. And we need help with the colossal expense of secondary education. Some of this is finally being addressed with the gravity it deserves, but we have a long way to go. It affects who makes it and who doesn’t. Many non-white and LGBTQIA+ students quit these programs without completing training because they feel marginalized, tokenized and misunderstood. This ultimately leads to mis- and underrepresentation in the industry, leading to the same reproduced art. It all feeds into itself. While not everyone goes to school to become an artist, it’s becoming increasingly important to have the credentials and the connections these institutions afford. And yet, 20-plus years down this career path and seven years out of college, when I ask myself if it was all worth it, I hesitate.

Structural Racism in the Arts Can Affect Anyone

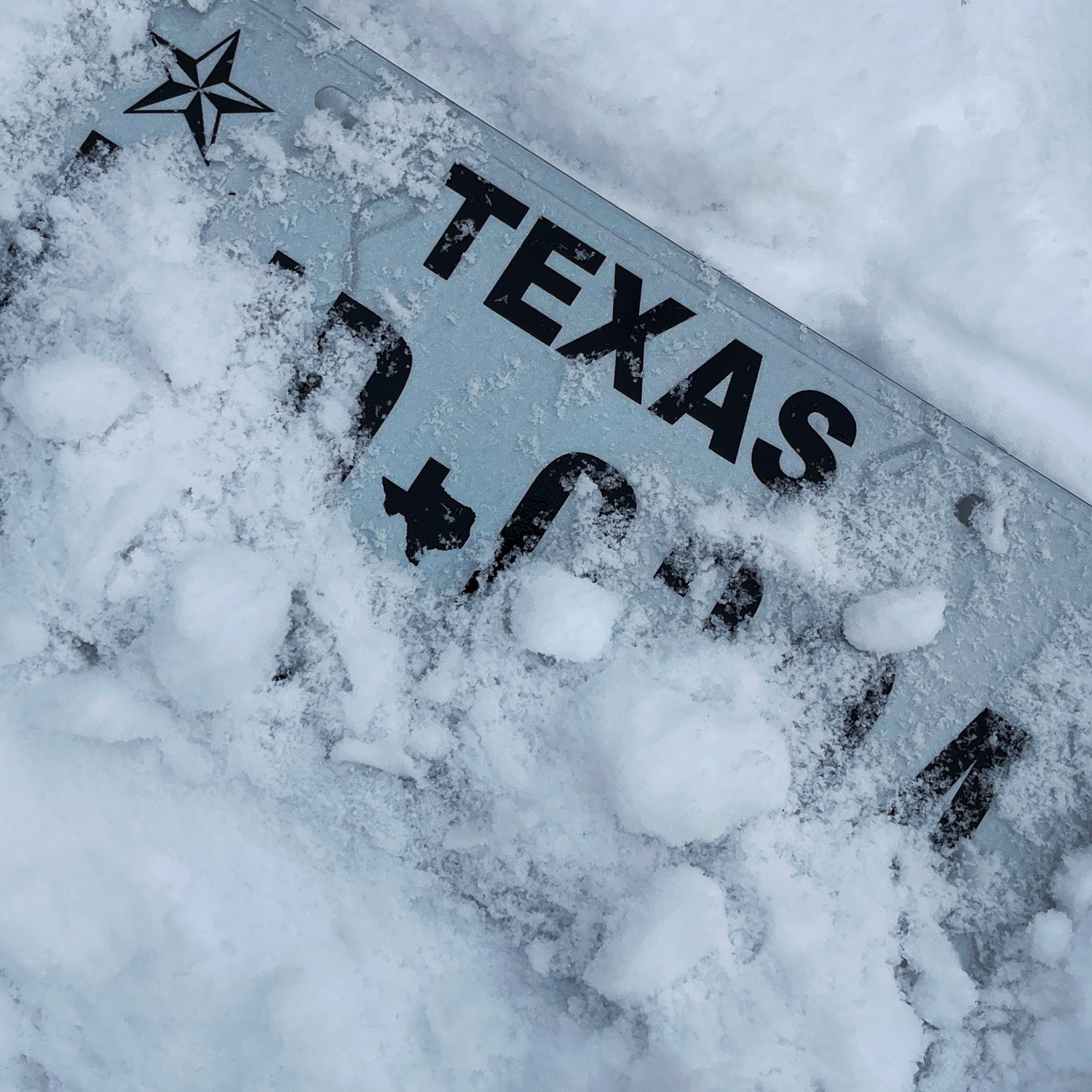

Writing this piece has unexpectedly torn me open—I’ve stalled a bit on the professional performance front, spending time in various day jobs, making a partial pivot to writing for the screen and stage, feeling discouraged and, for the first time in my life, doubtful of my choice. I have chalked up all of this vacillation to the fact that maybe I’m not pretty enough or not captivating enough, or that I’ve been lazy and stuck in my own way. Reading these reflections back, I am realizing that narrative is the direct result of a buildup of little traumas that have bred reluctance and demotivation. Most of all, it makes me see how insidious systemic racism (yes, that’s what it is) truly is.I am the best-case scenario of this. I am privileged enough to come from an educated, supportive middle-class family and am beyond prepared for this work. I’m set up to succeed. And even so, the powers that be, the -isms that “other” me, make success seem not only distant but impossible. I cannot imagine how the rest of us “others” have suffered in this regard. There is hope though. Because sharing this has freed me. Because like I said, I know in my bones that this is what I’m meant for. So here I am again—trying, flailing and failing. In the gutter, not just looking, but reaching for the stars.