I Was a Stand-Up Comedian as a Child: Here's Why I Stopped|The London Tube|A man pondering looking out of a window|A stand-up comedian

I Was a Stand-Up Comedian as a Child: Here's Why I Stopped|The London Tube|A man pondering looking out of a window|A stand-up comedian

I Was a Stand-Up Comedian as a Child: Here's Why I Stopped

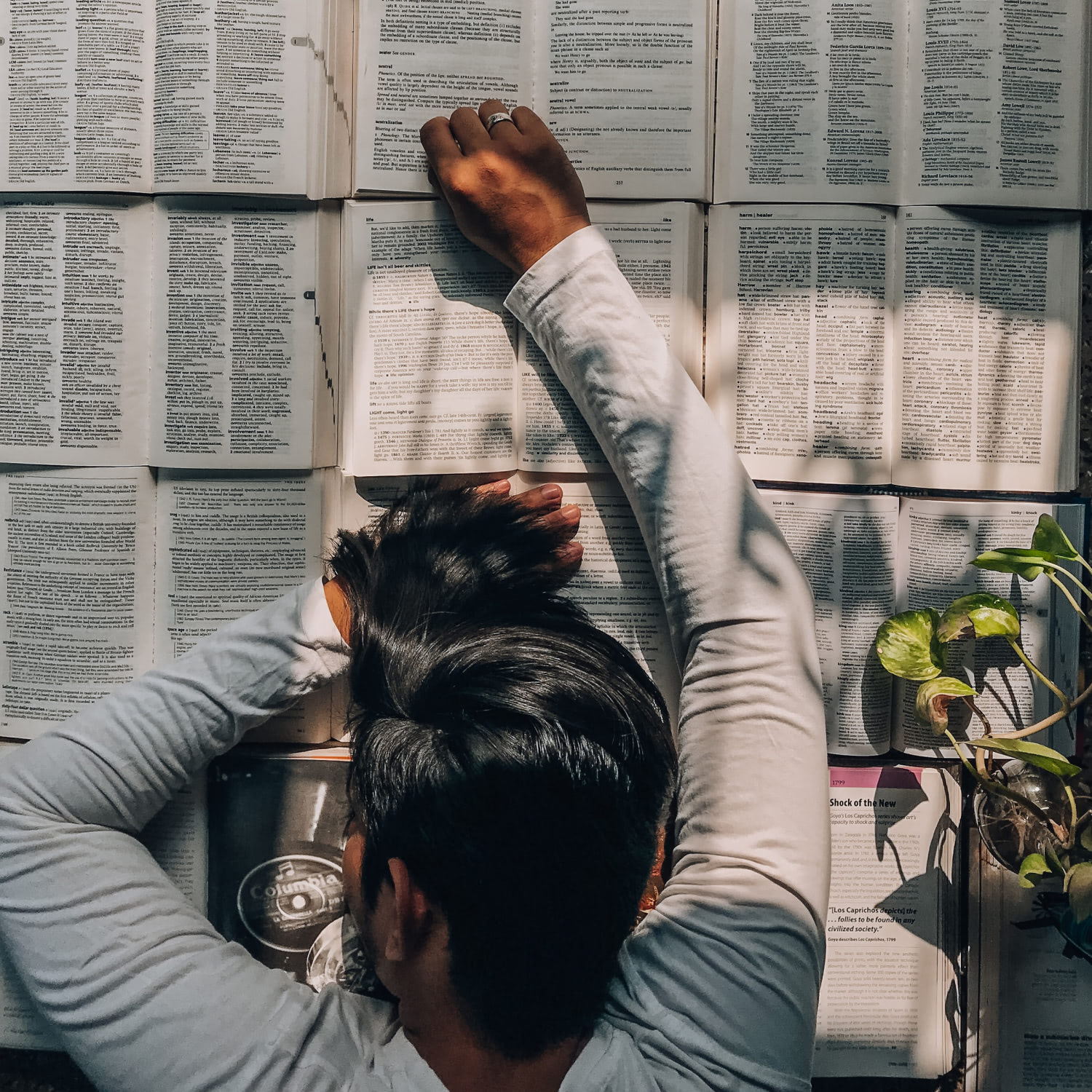

When I was 13, I was obsessed with making people laugh. It was like liquid approval. That counted for a lot as the nerdy kid who felt (and still feels) like he had to justify his existence. I decided I had to become good at stand-up. Living in London, I was able to find workshops that taught comedy to children. And being middle class, I was able to afford them. In comedy, like in most things, privilege starts early. The times I spent in those workshops are amongst the happiest of my life. They made stand-up seem attainable, despite my youth and inexperience. I would leave class feeling like I could fly. To this day, when I’m with someone and we walk past the building where the workshops were held I feel like I’m keeping a secret. Eventually, I became too old for those workshops and the gigs that came with them. It was time for me to grow up and do open mics.

When I was 13, I was obsessed with making people laugh.

Open Mics Require Time, Energy and Sometimes Money

Here, you also run into privilege. In London, an open mic can be on the other side of the city and run for hours. That means that getting to one involves travel costs, and coming back could involve walking home at night in a busy and often unsafe city. The day after, you might be facing a long day’s work on your feet. You might need to sleep, and so you aren’t able to come home late. Leaving an open mic early is frowned upon, though, and might mean you fall out of favor with the promoter. Promoters talk, so this is bad. And this all assumes you even have the energy left over from working all day to even make it out in the first place. There’s also no money to be made: Open mics are all free, and some gigs are even “pay to play,” where the club or promoter charges for stage time. This is less common, and almost universally shunned, but far from unheard of. And even “free” nights might request a bucket donation from acts as well as audience members.Overall, we see that people like me are at an automatic advantage. I was (and am) wealthy enough to afford repeated trips on the Tube to provide a service for which I was not being compensated. I didn’t work long hours doing manual labor. As a man, I was at considerably lower risk walking home at night. Consider also that a lot of open mics in London are “bringers,” meaning you only get to perform if you bring a friend. This is a problem when you consider that privilege tends to attract privilege. When privileged acts bring privileged friends, open mic comedians soon find themselves having to cater to a disproportionately well-educated, wealthy, white male audience. It’s the audience in front of which so many comics get their start. A lack of diversity in the rooms above pubs breeds a lack of diversity on TV ten years down the line. The people who watch that TV get the message that comedy is for a certain “type,” and the cycle continues.

Even When I Performed Well, I Wasn't Happy

This weighed on me, but only in terms of principle. Practically speaking, it was benefitting me enormously. But even then it wasn’t worth it. The enthusiasm and collaboration I’d enjoyed in workshops had been replaced by cliques which were rarely willing to give me the time of day. After two hours on the train and up to three hours of jokes about online pornography, I would come home from gigs utterly deflated. The night of a performance, or the morning after, I would evaluate my performance out of ten on a spreadsheet. (I mentioned being the nerdy kid growing up, right?) A crushing night might be a three or a four. After those performances I would sit in my kitchen for an hour, trying to process what had happened. The next day, I’d listen to the recording of the performance I’d made on my phone, reliving the disaster to see what went wrong. I would write down each joke and give it one to three ticks or, if it had gone down particularly poorly, a cross. Looking down at a page full of crosses is far from motivating. The closest thing I allowed myself to encouragement was a mantra, which I repeated in my head without being fully aware of it: “If I can’t be happy, I will be content.”One gig in 2018 was triple ticks all round. In my spreadsheet, I awarded myself a nine. It was the sort of gig you’d dream of, the gig that made the mental lows of all those threes and fours worth it. As I left the gig, trying to find some sort of a buzz, it dawned on me that I felt nothing. This was the first red flag that was big enough for me to notice. It still took me over a year to quit.That September, I came to university, and I decided I had to settle once and for all whether or not I was funny. Naturally, I started coming onstage in a fur coat and pretending to be a rapper. It felt good to retain the alternative streak that I’d found in the workshops from all those years ago, and bizarrely, it went over well with the audience. For the first time since I started open mics, I felt like I could tell people I did stand-up without being embarrassed. A year later, before I went into my second year of university, I had a couple of bad gigs. This may contradict my self-indulgent musing about not being embarrassed of my work anymore, but the truth is no one ever stops bombing. What was different with these bad gigs is they made me seriously consider whether or not I wanted to continue.

After those performances I would sit in my kitchen for an hour, trying to process what had happened.

Since Quitting, I've Become More Whole

The decision to quit came to me suddenly but gently, and a few years overdue. In an early draft of this article, I wrote that I quit stand-up the second I realized it wasn’t healthy for me, but that isn’t true. I’d love to say that it was, that I realized you’re allowed to trust your instincts and you don’t have to do something when you don’t enjoy it. What actually happened is I got good at stand-up. I’d finally “won.” If that hadn’t happened, I’d still be out there, doing something I didn’t enjoy, for free, with people who kept me at arm’s length.At school, I was a chronic overachiever. When you get consistently high grades, you start to see anything less than perfection as failure. When I used to tell myself, “If I can’t be happy, I will be content,” contentment was always in the future tense. It was reserved for when I was getting ten out of tens on the spreadsheet. Compounded by a culture that encourages competitiveness and tells you to “never give up,” perhaps it wasn’t surprising that I kept going. We are starting to wake up to this: The term “toxic positivity” has slowly been creeping into popular use. Of course, culture wasn’t the only thing at work—the worst part of me also wanted attention and fame, and to be better than the people doing porn jokes.Since quitting, things are better. The thing about thinking you’re funny is you can’t really help yourself. I help run a satire website for students at my university, and I’m not beholden to the approval of others to be happy. I’m not obsessed with the site being viral, or even successful. I don’t want the “top grade” in satire. I fear my spreadsheet days may be behind me. In a world saturated with an obsession about being popular, a term we don’t often hear is self-actualization. It’s a decidedly more solitary concept, and introspective. At least to me, it is the process of becoming whole. After quitting stand-up, a craft devoted to putting the needs of a room full of strangers above your own, I finally feel like I can put myself first. “Happy” was never a word I used to describe myself until the year I quit. It still isn’t the first word that comes to mind. (If you've made it this far, you’ll know that “concise” isn’t either.) But it’s progress.