Man by Fire|Files

Man by Fire|Files

Grenfell Tower: A Monument to the Exploitation of Kindness

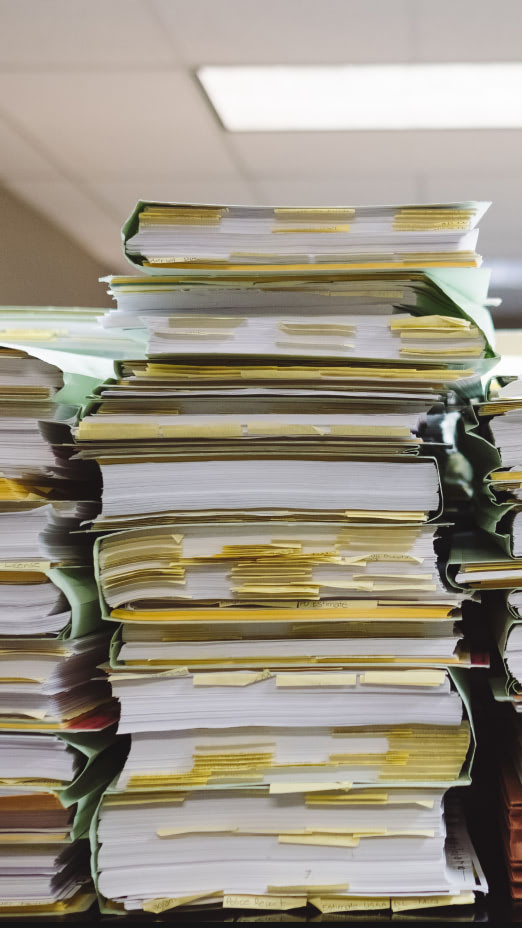

In the aftermath of the Grenfell fire, different people became involved in the effort to help out the people impacted by it, for very different reasons. Those of us who became professionally involved had a whole range of motivations. I personally was drawn in by both anger and the impulse to help. I know a person who lived in Grenfell Tower, who survived, thankfully. I react strongly when I perceive injustice, and the obvious negligence that caused such a disaster triggered my rage against the machine. I’ve also been a counselor, practitioner in substance misuse, housing and mental health services, and I knew my skill sets would be of use. After the fire, a new organization, the Grenfell Support Service, sprang up to offer roles that promised “a new way of working,” with less bureaucracy and more hands-on client work to “develop therapeutic relationships with the survivors.” The job description spoke to my concerns about the health and welfare sectors in the U.K.—larger case-loads, fewer resources, sensitive work being foisted upon unprepared volunteers, unnecessary paperwork. The kindness and largesse of far too many are being exploited by services that, by rights, ought to be funded properly, as the U.K. has since WWII. Often, in a bid to keep files up to date, practitioners across a range of services now fabricate (or guess) when completing, for example, a treatment outcome profile survey form, which is designed to map outcomes in drug treatment programs. It’s bollocks at best, and produces data that is as valid and accurate as a piss in the wind.I want to share some of what I saw, some of what I did, but mostly what I learned. My involvement in the Grenfell Support Service revealed consummate professionals battling systemic and structural issues that relegate human wellbeing to a distant second to the economic imperative. This is essentially a critique of neoliberalism and its tendency to exploit acts of kindness to save money and protect profit. After all, why pay people a decent salary when you can simply exploit the urge of decent human beings to help others?

This is essentially a critique of neoliberalism and its tendency to exploit acts of kindness to save money and protect profit.

Grenfell Happened Because of Greed

On June 14, 2017, the night sky over London W10 lit up with a strangely beautiful orange glow. It was a raging fire mercilessly destroying lives and property, a scene out of Dante's Inferno, or a Bosch painting or even the Blitz. A dark, ethereal beauty announced the fact that the gates of hell had been pried open by wanton neglect.Wealthy locals had complained that the aesthetics of Grenfell Tower were affecting their property value. In order to save money, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) cut corners on re-cladding it. The catastrophic consequences for the powerless—72 dead and countless lives ruined—brought out both the best and worst in people. At the height of the fire, on floors 19 and above, the fire roared at 1600 degrees Celsius. The morning after, as Grenfell Tower stood like a smoldering monument to inequality, I made my mind up that I would find a way to work for and with the survivors. Four months later, I was attending a training day for new recruits to the Grenfell Support Service (GSS), which had been set up by three collaborating charities and commissioned by the local authority to provide a response of the highest caliber and some measure of oversight. Well-trained, well-resourced staff were to oversee individual cases and act as a bridge between the local authorities’ housing departments, benefits agencies and other charities involved.On the induction day, it was clear the caliber of staff was highly qualified. Most had years of experience. We were given long talks about the “gritty” nature of the work. Our stomachs were tested with graphic accounts of the last moments of so many human lives. Calls had been made and recorded as people succumbed. We got to hear some of them. One elderly man had lain back on his bed, his faithful dog clutched to his chest, as the smoke and fire reached them. One young man saved everyone on the fifth floor by battering on doors and begging his neighbors to get out. I was told by a survivor that she had seen war in Africa, with airstrikes and artillery, but she had never seen anything like the horror that unfolded in Grenfell Tower, where at one point over 50 body bags were lying around, waiting to be removed from the scene.Warnings of the tower’s vulnerability to fire had been sent to RBKC since 2009, when residents grew concerned about the state of the electrical system and lack of sprinklers. At the time, RBKC held cash assets north of $300 million. They could easily have afforded to ensure the safety of their residents.One of the problems all health, social and welfare services in the U.K. now face is bureaucracy. As sociologist and philosopher Max Weber warned us a century ago, if anything was going to stifle and hinder the progress of humankind, his money was on the iron cage of bureaucracy.

One young man saved everyone on the fifth floor by battering on doors and begging his neighbors to get out.

We Came to Help but Ended up Swamped With Paperwork

During our training at GSS, we were regaled with a new vision for responding to disasters, one that prioritized the therapeutic work that traumatized children and adults need. Paperwork was to be kept to a minimum and all data was to be kept under lock and key.With my background in the substance misuse field, I was given cases where alcohol or drug use had become problems since the fire. It was rewarding, hands-on, challenging work and the outcomes were gratifyingly good, even if “good” was as simple as helping someone get to a hospital or, in one particular case, get an individual financial support after months of living in abject poverty. It felt like important work, and was, despite the challenges, deeply rewarding.On my first day on the job, I was forced to kick a door in, along with police and an ambulance crew, to get to a seriously unwell substance user who’d been affected by Grenfell the hospital treatment they desperately needed. Then I filed a standard incident and outcome report and moved on to the next task.As the weeks rolled by, though, I noticed that one after another, practitioners were being asked to leave. At the same time, slowly but surely, RBKC senior staff began showing up at meetings. A new range of paperwork was developed to “evidence” our outcomes. We were being slowly absorbed by the RBKC machine.The fact that many of us had taken pay cuts to take our GSS jobs, and the fact that a huge amount of the work done on the front line was increasingly done by volunteers, were the red light to me. The ideal we’d been sold during induction had, it seemed, gradually eroded. Even the three managers I reported to shifted their daily emphasis within the team meetings towards completing “star charts”—a tool, like a TOPS form for measuring the most subjective of outcomes.

Greed Is Keeping Grenfell Survivors From Getting Justice

The “independent” Grenfell Support Service was absorbed, almost by osmosis, into the wider structures of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Despite the unique horror of the Grenfell Tower fire, the deaths and the professed determination to do things differently, the local authority—itself under investigation because of the fire—was able to impose bureaucratic frameworks that ensured it. This disaster has exposed both the finest of human impulses to help and the greed and cynicism that sadly lie close to the surface of human experience. As Grenfell Tower burned, one man drove several hours from South Wales to pretend to be rescued. A finance manager at the local authority stole over £60,000 from the Grenfell Support Service funds. One family claimed to have lived at an address in the tower that never existed. Grenfell Tower offered us a collective opportunity to do things differently, to put health and wellbeing center stage. Unfortunately, under our current neoliberal paradigm, measurement is king, outcomes of the most subjective kind must be rated. I’m with Max Weber. If we don’t start binning the bureaucracy, we’ll reach a point where movement—both metaphorical and literal—will be bloody impossible.