Man covering face|People walking|Hanging sneakers

Man covering face|People walking|Hanging sneakers

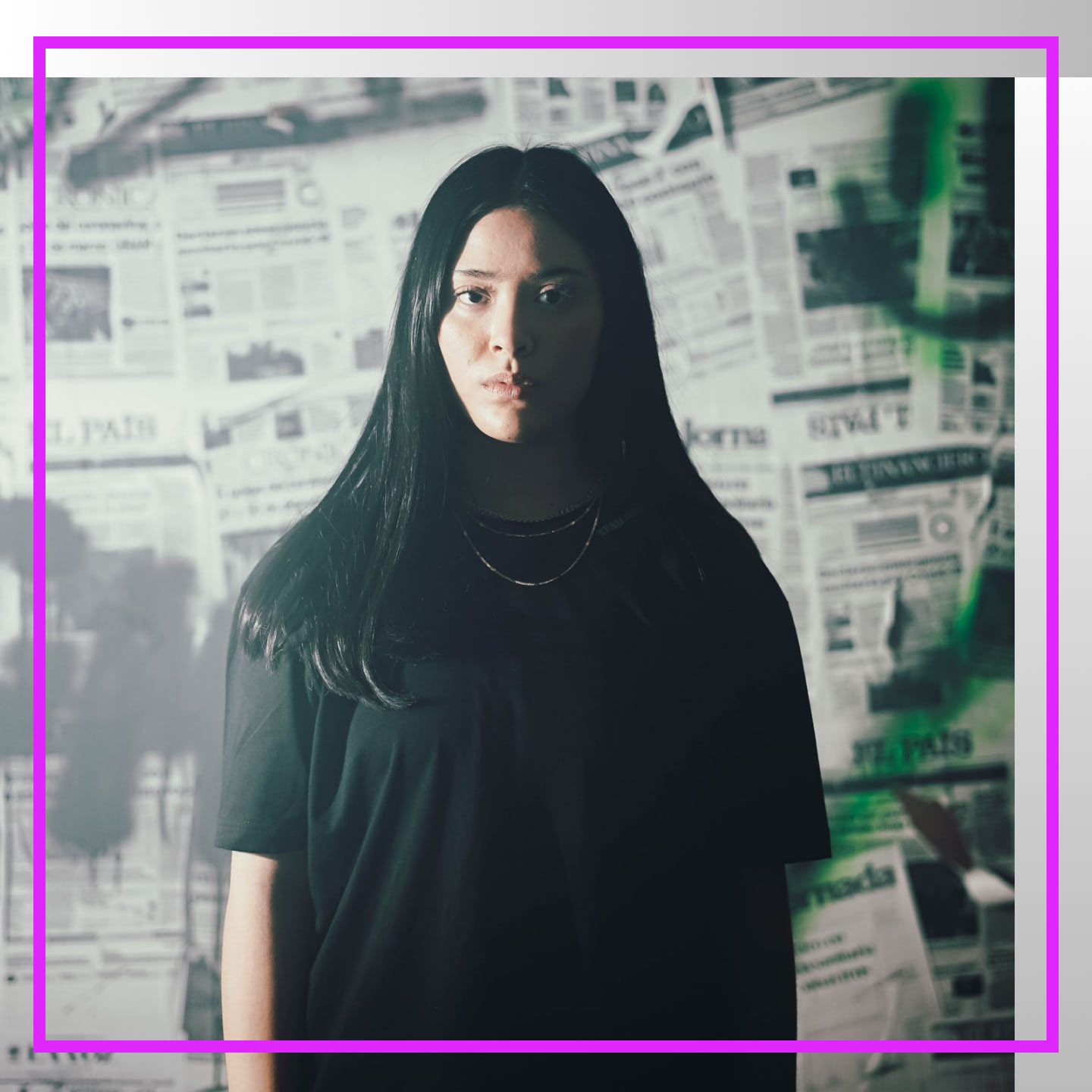

I Was a Gang Member and Now I’m Finally Free

When you meet a gang member, your initial thoughts are liable to be negative. This type of person needs to be locked away, one might tend to think, for the safety of the community, and the protection of society as a whole. As a person who joined a gang, did drugs, committed crimes and was ultimately locked away in the name of societal protection, I can tell you with 100 percent certainty that this is not the just way.I speak for myself when I say that I made an active compromise to join the gang, in the pursuit of identity, acceptance, family and safety. I can speak for others, both in my position and not, by saying that we are all taught that approval from peers is more important than the things we dream of, or the people we love and admire. We live in a model that values power over others over innate personal ability. We forget the more vulnerable person who once dreamed and was scared in the process, almost as a defense mechanism.I learned early on that the little boy who loved and laughed and cried was weak and could not possibly survive in the world. I walked this education out into membership, and eventually leadership, in a gang—a hardened mind, violent crimes and a worldview based on the idea that it was my gang and me against the world.This view cost me almost 21 years of my life and not just because I was incarcerated. I did spend over two decades inside the walls of juvenile facilities, group homes, foster care facilities, jails and prisons. The actual time in these places was not the most impactful price that I paid.The real sacrifice I made for the “power over others” mentality was that in those 21 years, I ceased to be me. I was only the person others wanted me to be. This loss of identity was pervasive and spread like a virus throughout my entire being as I got older. For much of my life, I sought approval, all the while telling myself—and fully believing—that I didn't give a fuck what other people thought of me.The combination of traumas and angst I had experienced in my younger life created a recipe for disaster.Patriarchy informed me that the only way I could claim a place in the world was through the false notions of superiority and power that I got from my gang identity—that these people were the only ones who had my back, and that without them I was completely unsafe in this world.The mask of a gang member became manhood for me, but this mask was also a security blanket for a scared and hurt child, encompassing every aspect of my life. I felt safe and sheltered from harm in the short term. In the long run, however, this blanket closed the real me away, it locked me from everything valuable in life. That mask became the real prison—everything else was circumstantial.

They were the only family I could depend on.

Why I Joined a Gang

I first got involved in a gang at 13. I was a runaway escaping a drug-addicted and abusive father, sleeping in parks, abandoned schools and behind grocery stores. I was a small and gangly kid, and while bunkered down in a dark park one night, a group of loud kids walked through and interrupted my drunken sleep. Immediately, I was struck by this group’s collective presence.These young men had all of the things I felt I didn't have: confidence, grit, style, intimidation factor. I was a small, longhaired runaway who spent most of his life being beaten by his father and said nothing. These kids had everything he'd taken from me. They could have jumped me and things might have been different, but instead, they talked to me. Embraced me. Invited me to go with them to a show. I could have declined the invitation but, in a society where young boys are taught to admire domination and force, my clarity of choice was blunted by the more present desire of wanting these boys to like me. The thought wasn't as clear as that, but it was almost instinctual that I gravitated towards their confidence and force. Within minutes, I knew that I wanted to be just like them.Over the next days, weeks and months, I learned their mannerisms. I picked up their style of dress, and through a series of actual fights, I was taught that to be a part of this group—and to get the respect they had—I had to be willing and able to hurt people. This seemed less terrifying than the thought of losing this newfound acceptance. I also learned that to excel, I needed to do crazy things, often violent, to gain a reputation. That way, people wouldn't want to fuck with me, and I won the added protection of having my new group in my corner when things got hectic.What did hectic look like? It looks like attacks from others that I had been trained were my enemy—and I use the word "others" quite deliberately because everyone outside of our small group became classified as the "other." Unimportant. Not as good. Not worth anything in some cases.Over the next few years, I found myself expelled from school, detained and continually arrested. Eventually, I was deemed undesirable by the courts and placed in a juvenile facility. After several times through this cycle, the juvenile courts determined that my house and family could not adequately manage me and, as a result, I was designated a ward of the court. Basically, that meant that the state was my new parent. I was thrown into foster care. One would think that my gang identity would end there, at the point where freedom ends and custody begins.But inside these juvenile halls and foster care group homes, I was introduced to hundreds, even thousands of other children who had made similar choices. As a response to trauma, kids had sought protection and security in the pursuit of manhood through violence and objectification—through power over others: kids who had different skin tones, attitudes, mannerisms and gang names, but ultimately the same security blanket.Despite the external differences, society had classified us all as "delinquent,” but what we really were was traumatized. We had responded exactly as we were socialized to, and society was afraid of the results.

I Became What Society Wanted, and It Wasn't Myself

I never went home.I don't mean that I was never released. At 18, I was kicked out of the foster care system, but by this point had ceased to ultimately be myself. I found my way to jail, then to prison, and almost always for the gang's benefit that I still considered my family. Upon arriving at prison for my first term, I remember thinking that it really wasn't that much different than foster care and juvenile hall. I even saw some of the same faces that I knew from my years in group homes. We all wore our masks of confidence and brazenness. We all pretended like nothing affected us and hid all our other “weaker”—I would now say more real—emotions, like sadness, fear and insecurity, behind anger.After all, anger is socially acceptable and vulnerability isn’t. In the process of learning manhood, how many of us were told that boys don’t cry? What I had become, and was seeing daily in prison, was the living result of that lesson.We were a group of hurt people without any ability or knowledge of how to respond to that hurt in a way that healed. Sure, we did terrible things, and society had either openly or suggestively determined that we were "bad." But nothing about locking us in cages and separating us from the world was intended to treat that hurt. There was nothing to live for in that environment, so on the inside, I lived for my gang the same way that I did on the outside—with the entirety of the version of me that they had created. The gang was always all that I had, and even more so locked up.They were the only family I could depend on.I pushed for that gang, even when it was harmful to me, and this perspective got me a second bid with double-digit numbers. It got me into numerous riots, staff assaults and violent altercations, and gave me new cases while I was already in for an extremely lengthy period.In every instance, I knew my reputation was growing. That fed me more than the fact that my parole date was moving further and further away. The thinking was simple: There was nothing out on the streets for me anyway. In there, and in the gang life, I was someone not to be fucked with, and therefore I was safe. Whenever I was challenged (and I was on many occasions), I responded with a degree of brutality that would get my message across: Do not fuck with me. Whether through prison political moves or actual violence, I maintained my safety.But I was never really safe, and I was never really myself.I could have been lost forever. I had started my second term at 21, and by 30, I had no intention or clear vision of going home. If it did happen by chance, nothing I did showed that I had any intention of staying home. The system had done what it was designed to do: create a permanent resident in its institutions. The system provided no means of treatment for my traumas, no rehabilitation method for the issues I had developed. It only gave me a number, meals and the lesson that I would always be marked as less than in society's eyes. And again, I assert: This is what the system is designed to do! The millions of other people incarcerated in America and I are not failures of the system. We are byproducts of patriarchal control and mass incarceration. I turned out exactly like the system meant me to.

Real Talk Gave Me a Way Out

It wasn’t some state program that saved me from myself or some benevolent staff member who made me realize my worth. No teacher or preacher singled me out and lifted me up.This isn't a Hallmark movie. But there is a happy ending.I eventually found healing and peace. I was able to reclaim myself. I was freed and now I live a life based on integrity and love for others. I found my salvation in the very men that I was housed with in prison, and in the real and raw connections made as we discussed why we did the things we had done.A whole community of people, of all shapes and sizes and colors, had come together to discuss what role that patriarchy played in their lives. If this seems like an unlikely conversational topic in prison, that’s because it was. But real conversations centered around healing and discussing toxic masculinity are crucial—they’re the key to curing what has sickened society. And in doing this, I found myself again.I also found out that what we have been taught is justice is not just at all. Justice has nothing to do with taking from me because I took from you. That revenge model stems from the same patriarchal tree as my original choice to seek acceptance and hurt others. What my peers and I did inside—and still do—is real justice. We were harmed, we openly and unabashedly discussed why we chose to harm, we found the systemic cause and we worked to uproot it. We began the process of healing, and of making society better as a whole. Justice is achieved when the behavior and the systems that led to harm are transformed for the better.I committed to that idea in a visiting room at a remote prison, and my life transformed. I came home, but I continue to go back into prisons and hold these conversations with my peers who are still inside. I’ve broken the cycle and removed my chains. Finally, I am free.