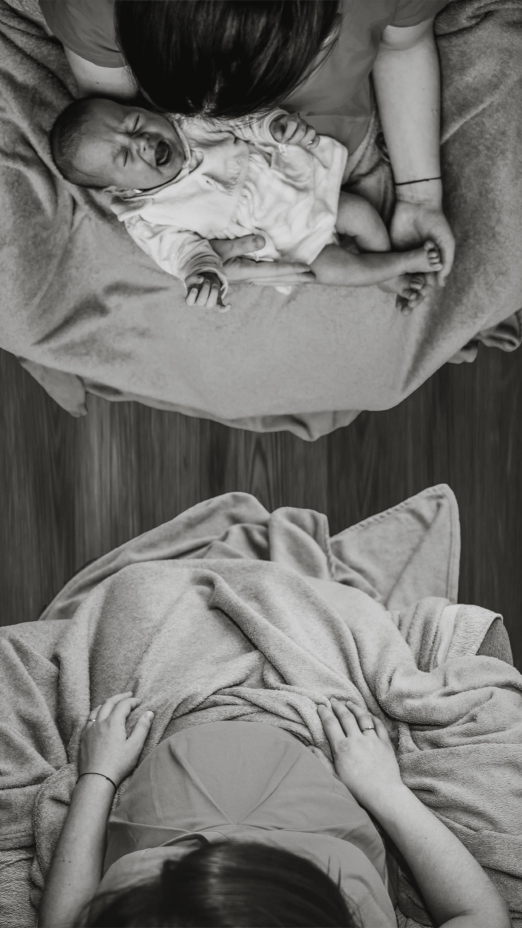

Birth Strike: Coming to Terms With Climate Grief|A baby cries between two women

Birth Strike: Coming to Terms With Climate Grief|A baby cries between two women

Birth Strike: Coming to Terms With Climate Grief

A family video of me taken when I was six years old shows me dutifully feeding my youngest brother via the bottle. My dad asks me how many kids I want to have when I’m older and, without skipping a beat, I say “Five.” He asks me how old I think I’ll be when I start having these five kids; I pause for a minute to consider before answering, “23.”Five kids—it is ludicrous to even think of at present. By my own timeline (and with reference to my mother’s reproductive schedule), I should have at least three kids in tow by now. But I don’t.I don’t know how to reconcile the climate change work that I do with what I consider my most innate and defining call: to be a mother.

I don’t know how to reconcile the climate change work that I do with what I consider my most innate and defining call: to be a mother.

How My Maternal Instinct Has Exacerbated My Climate Grief

Wanting to be a mother constitutes some of my earliest memories, such as holding my favorite dolls, putting balloons up my shirt and pretending I was pregnant, feeding my siblings and fighting with my sister for the right to push our baby brother in the stroller, taking my brother to my kindergarten class to proudly present him for show-and-tell.As I grew up and tried to tease apart how much of my desire to be a mother was just indoctrination and how much was actually instinctive, I had to admit to myself that I was secretly relieved when studies about apes and chimps showed that males and females showed the same evolutionary proclivities: many girls are drawn to dolls, many boys prefer wheeled toys.The bulk of my adult life has been working with a large intergovernmental environmental organization dedicated to finding solutions to seemingly intractable environmental problems. I work within the climate change team; as my knowledge of the climate and ecological crisis evolves, it doesn’t square easily with bringing more life into the world.Right now, I’m shocked over how the COVID-19 world lays bare every crack, every fissure, every social injustice and climate inequity. The world’s response to this pandemic illustrates, in some respects, that those who possess the fewest resources to deal with the virus will bear the worst consequences of the virus. For example, the poor, the uninsured, the migrant, the minimum wage worker—these are the people who are forced disproportionately to bear the negative consequences of the spread of COVID-19.And our climate future looms as even more dismal.Is a birth strike a sign of moral protest? Or a tacit acknowledgment of defeat? Is having a baby a defiant act of optimism? Or a hopelessly selfish and shortsighted choice?What is the balance between hope and realism? I draw inspiration from Angela Davis’ dictum: “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” Yet what act more radically transforms the world: a birth strike, or raising the next generation of climate warriors?

Yet what act more radically transforms the world: a birth strike, or raising the next generation of climate warriors?

Choosing Not to Have Kids Seems More Reasonable Than Ever, Now

As I grapple with this question, I consider how this question of whether or not to have kids was addressed in Meehan Crist’s recent article. She writes, “[Y]ou will feel—with rage, or sorrow, or relief—that it has been made for you. But the fantasy of choice quickly begins to dissipate when we acknowledge that the conditions for human flourishing are distributed so unevenly, and that, in an age of ecological catastrophe, we face a range of possible futures in which these conditions no longer reliably exist.”And this cognitive dissonance or disconnect takes on a new degree of dread as this pandemic seems to portend what the future might hold.In Crist’s article, she also narrates the moment when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez voiced the question that still seems very impolite and not politically correct “while speaking to her millions of Instagram followers via live stream: ‘Our planet is going to hit disaster if we don’t turn this ship around,’ she said, looking up from a chopping-board littered with squash peel. ‘There’s a scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult.’ Her hands fluttered to the hem of her sweater, then to the waistband of her trousers, which she absentmindedly adjusted. ‘And it does lead, I think, young people to have a legitimate question, you know, should…,’ she took a moment to get the wording right: ‘Is it OK to still have children?’”I think a lot about climate grief and how to deal with what this planet might look like in 30 years or 50 years, but I still can’t wrap my head around what that means for my reproductive future. And now I’m adding the overlay of pandemic grief as I grapple with this question. I recognize that a post-COVID-19 world—where we should make dramatic choices to right this ship and choose to redefine the new normal with nature at the core of our decision-making—may not be a livable one. As the current bailout is doubling down on oil and the future looks even more uncertain than before, maybe I need to put this question to bed: It feels like the future is already here.