How a Changing World Is Affecting Our Children's Development|Where there are chickens, there are also hawks.|Kids are struggling to break away from their screens during the pandemic.

How a Changing World Is Affecting Our Children's Development|Where there are chickens, there are also hawks.|Kids are struggling to break away from their screens during the pandemic.

How a Changing World Is Affecting Our Children's Development

The moment of drop-off, when that wave of heat and sound washes over the kid stepping through the school door. Focus, boredom, distraction. Obnoxious boys imitating their dads’ casual misogyny, girls fighting back. Lingering in the school bathroom getting into small trouble. The relief of the walk to a friend’s house after school, stopping to buy candy with the dollars crumpled in their pockets. The secret lives in young minds: a multitude. Turn childhood social life inside out and you see it’s a magic box, much bigger on the inside than the outside, a vast interior. Incipient romance, searing pain, wild-eyed anxiety.My daughter’s life has shrunk, like it has for most of us. Early in the pandemic, we made a pod with a couple of other families, but then one of them moved to a far more functional country on the other side of the planet. Our daughter (let’s call her Z) wasn’t close with the other family’s son. The arrangement petered out. Winter set in.Now she spends her days with her screens—from iPad to Switch to school-issued Chromebook. We try to help her through the drudgery of a fifth-grade year happening online. We bring breakfast and lunch to her room as she listlessly completes math problems. We rub her back and try to engage her. She gets excited about Minecraft and not much else.Except chickens.

I have no clue what sort of consciousness, individual and collective, will emerge among this pandemic generation.

Where There Are Chickens, There Are Also Hawks

I was in a Zoom meeting when the hawk landed on some trellising, outsized like it had been photoshopped unskillfully into the scene out my office window. For a moment, I was frozen by the cognitive dissonance. I live in a small town in New York's Hudson Valley, where the nonhuman world is richer and closer than some places, but still greatly diminished. The hawk was too big and full of violent potential to make sense in my backyard.A second later, I was scrambling from my screen, calling out to Z to get her chickens into their run. She got outside first. The hawk must have left at the sound of the door opening, and so the chickens clucked their way safely back to the part of our yard we now call Chicken Alley.The hawk keeps coming back, though. Z spotted it in a tree maybe a hundred feet away. It has a favorite branch, where it is clearly waiting and watching.This life-or-death matter is compounded by the everyday drama we’ve lived with since we picked up our half-dozen chicks back in the spring. The pecking order isn’t just a cliché: Marshmallow is at the bottom, Chickpea is at the top. Cub is somewhere in the middle, and she tries to assert herself by attacking Marshy. She dominates the nesting box, bloodying anyone who needs to lay an egg.The consequence of these battles is largely sonic, and so we live our days against a backdrop of plaintive chortles and angry screeches, rhythmic bawks that loop and fade like a William Basinski album. At its most severe, the cacophony sends my daughter running outside to perform chicken conflict-resolution, sometimes five or ten times in the course of a single school day. So far, her teacher, on the other end of Zoom, hasn’t complained. Maybe she doesn’t know Z’s gone (camera off, mic muted). Or maybe she does, given that Z sometimes stays out for a half-hour, soothing her birds, separating combatants, cleaning wounds. Z’s a good student (Minecraft addiction notwithstanding), and I’m sure her teacher has enough on her plate trying to hold a virtual classroom together.Besides, there’s not much you can do once a kid’s left the screen behind.

One Is Too Few, but Two Are Too Many

I have no clue what sort of consciousness, individual and collective, will emerge among this pandemic generation, the kids like Z perched at the edge of adolescence, living online. She falls asleep at night to YouTube videos—ASMR soap cutting, slime smushing and bubble popping. If dreaming of electric sheep is a thing robots might do, what does that make all of us now?This posthuman social experiment might be a late stage in our transfiguration from flesh to data, or it might be something for which we don’t yet have an adequate language. The feminist theorist Donna Haraway famously and cryptically suggested that “one is too few, but two are too many.” Kids these days are living somewhere beyond the radical individualism of our failed American economic experiment, but that doesn’t mean that the alternative is simply more relationality, more of you and me. Pronouns are under serious pressure, and for good reason, but as troublesome as “he” or “she” might be, “I” may be an even bigger problem.I wonder whether Z’s screen time and chicken time might be more aligned than someone like me—born on the cusp of Gen X and Millennial—can easily see. She tells stories she heard on YouTube as though they’d happened to a friend.Z knows what happens to most chickens in this country; the PETA website isn’t hard to find, and while I wrestle with this decision, I’ve placed no parental controls on her devices. For most of us, chicken is, like any number of other “food products,” more metaphor than living thing—an amalgamation of imagery and ideas that have little to do with the lived reality of either factory-farmed chickens or those who are lovingly cared for like Z’s little flock. We hear “chicken” and think of the cartoonishly crisp-skinned, roasted chicken paraded online as comfort food, even as activists fight to win actual, living chickens a single square foot of space in the factories, where birds collapse under the weight they’ve been bred to put on too fast, and die and rot among the living. Z would tell you about these horrors, if you’d listen. During a class unit on human rights, she clearly rattled her teacher by asking, “What about chicken rights?”Z sees chickens as chickens, revels in their dust baths, expects nothing other than that landbirds will be landbirds. She doesn’t need them to be anything but what they are, yet still she identifies with them.

Z knows what happens to most chickens in this country; the PETA website isn’t hard to find.

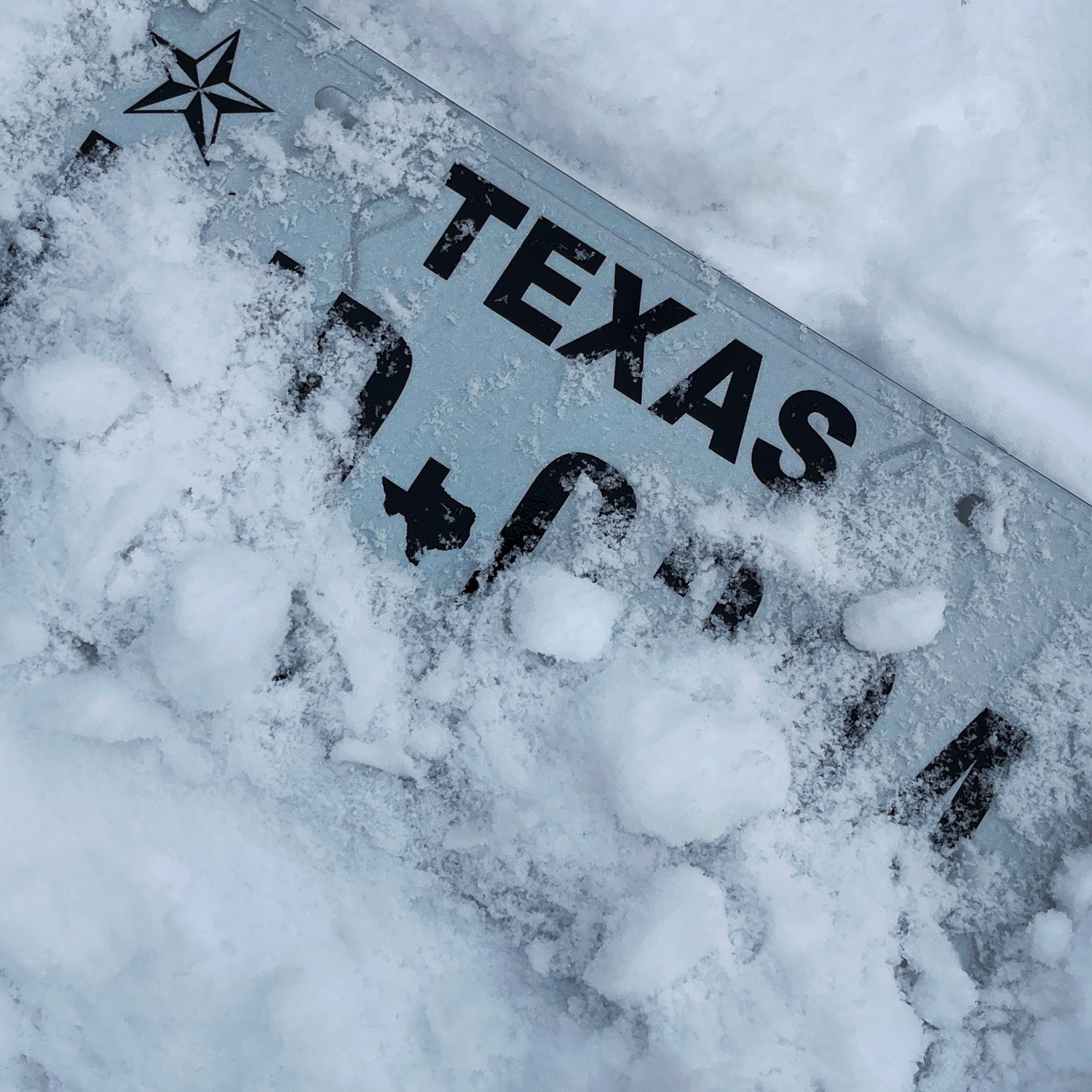

Our Educational System Wasn't Designed for the World We've Made

Our public education system, from kindergarten to universities, was founded on the idea that we were educating citizens for democracy, even if we’ve always fallen far, far short of that ideal. But now it treats students simply as human capital being shaped for use in the market—not entirely unlike factory chickens.Remote learning has only amplified this. Kids and parents alike now long for the everyday life of school that we’ve lost. Mental health professionals and scholars of education warn us of a crisis in the making. We subtracted the social part of school, leaving behind only content delivery, and found we had it backward: School, primarily, was the social part. What’s left is a chicken factory.When we talk about emergent distributed consciousness, we don’t usually talk about chickens. And we certainly don’t talk about chickens and humans together. If working through complex social realities is the heart of education, then this past year has in some ways expanded the social field for Z, tying her to a more-than-human social web both less and more real than what we pretended was normal before. From my office window, I often see the chickens roaming the yard, scratching at the grass and pecking, Z right with them—another biped bowing down to the earth. This seems, somehow, not as different from her constant stream of YouTube videos as one might think.Living another way means we have to watch out for hawks. In our rapidly warming world, hawks—broadly conceived—are everywhere. They’re a far more nuanced problem than the equations Z solves over and over on the math games she’s required to play on her Chromebook. Nothing’s natural now, anyway, or everything is, and so we’ll have to wake up from the illusory safety projected by the old way of thinking about the world. Self and other, human and animal, sky and land, predator and prey. We’ve been killing binaries for a while, but some aren’t mere projections. We aren’t individuals—humans are animals. Invisible particles way up there are slowly cooking us down here, but a hawk will kill a chicken, fast. Kids these days see our bullshit. And they’re increasingly comfortable muting it and running away, fast, toward what they can save.