The Doe’s Latest Stories

The Generational Divide Increases With COVID-19 and Climate Change

When Social Security was enacted in 1935, poverty was far more prevalent among the elderly than any other age group. That year, nearly 80 percent of Americans aged 65 or older lived in poverty. At present, fewer than 10 percent of Americans over 65 are under the poverty line. This resounding success is one of the most laudable transformations of American society since emancipation and women’s suffrage.But our successes in alleviating the wretchedness and precarity of poverty for our elders wasn’t achieved in a vacuum. Today, people under 18 are more than three times as likely as the elderly to live in poverty, with all of its attendant illnesses, wasted potential and deaths of despair.

Why There’s an Age-Related Conflict in the U.S.

In a very real sense over the past century, a generational wealth transfer has been delivered to the elderly and away from the young.I hasten to add: none of this is a call to immiserate the elderly. I have a lifelong, warm, loving relationship with my elders and consider my grandfather the lodestar for masculinity and parenthood. My grandmother was a Second Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps and an all-around badass. Much of the benefit that accrued to these elders (through Social Security and otherwise) are outweighed by the service they gave to our country and planet, and by the love and care, they’ve demonstrated to us and our families.But, surely, we as a society didn’t mean for elderly poverty alleviation to come at the cost of life prospects for today’s youth.Surely, we aren’t so enamored of a comfortable old age for our elders that we’d abandon our children to a future in a disease-ridden, environmentally despoiled hellscape.Surely, we’re not intending to create a zero-sum game between protecting the elderly and preserving a future for the young.But maybe we do? Maybe we are?

The Coronavirus Perfectly Illustrates the Sacrifices Young People Make

I have spent over two decades working in global public health aimed at decreasing child mortality, and I despair of the world that we are leaving to our children.By some estimates, the median age of COVID-19 mortalities in the US is higher than the current life expectancy at birth for someone born in 2020. More than just signaling that we are willing to hamstring our young by not investing in their futures, it means that we are, in Modest Proposal fashion, cannibalizing one impoverished group (the young) to feed the wealthiest (the elderly) by taking years of life away from the worst off and transferring these years upwards to well-off elders who already have had more years of life (and at a higher standard) than those born today can possibly expect.A disproportionate share of the costs for our COVID response—from short-term privation and isolation to long-term decreases in job prospects, credit ratings and earning potential—are borne by people with extremely low risk of mortality or complications from SARS-CoV-2. In essence, young people are asked to sacrifice for the good of people who’ve already gotten more out of the world than we’re ever likely to get.

In a very real sense over the past century, a generational wealth transfer has been delivered to the elderly and away from the young.

How Baby Boomers Screwed Us

We live in the first generation in human history expected to live shorter, less healthful lives than our parents, and this deprivation is accelerating. Today’s 35-year-olds now have been subjected to two “once-in-a-lifetime” recessions, while today’s 80-year-olds suffered exactly zero GDP declines greater than 5 percent in their entire working life. And these same 80-year-olds, in the wealthiest tranche of society, will likely live out their retirement with the full complement of Social Security and Medicare benefits (based on their life expectancy).In contrast, today’s 35-year-olds will get to watch the Social Security trust fund reserves become fully exhausted in 2037, and the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund become insolvent in 2026. (N.B. in both cases, these social safety net programs will be able to limp along at lower levels of benefits for years afterward. However, that we’re willing to give wealthy, aged people more safety net protections and resources than impoverished young people is both unjust and terrifying.)

It’s Fair to Say We’re Battling Gerontocracy

And this debt to children born today—this intergenerational inequity—is, if anything, worse on the climate change front. In both the climate change and the coronavirus cases, a gerontocratic ruling class allocates itself the benefits from the status quo, and puts the costs on the youth’s tab. Today’s 80-year-olds have the highest carbon footprint of any generation, and have injected volumes of CO2 into the atmosphere, all of which will be around for decades for the rest of us to face. Gallingly, this age group is also the most likely to “disbelieve” the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change.Gerontocratic systems, from the Soviet Union to modern theocratic nightmares like Iran and Saudi Arabia, to the Roman Republic, do not end well. If we are consigned to a zero-sum struggle between the old and the young, perhaps it is time for the young to stop cooperating with evil. To paraphrase and repurpose Marx: children of the world, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.

Why the Paris Climate Agreement Is Bullshit

I am intimately familiar with the international response to climate change: I’ve spent two decades negotiating treaties like the Paris Agreement.And so I can say this, with some degree of certitude: It’s total bullshit.How many major industrialized countries are on track to meet their targets under the Paris Agreement? Zero. Rich countries know that we're not going to get ahead of climate change; they've already begun the process of transforming themselves into gated communities.Perhaps the most distressing aspect of the Paris Agreement isn’t the fact that every major developed country on earth hasn’t yet enacted policies that would meet their pledges. Neither does it lie in the disparity between nationally determined emissions targets and pledged policies, as infuriating as this hypocrisy is. In fact, even if every major developed country met all of its pledges, we’d still be on track for roughly three degrees Celsius of warming by 2100—or double the Paris Agreement’s nominal goal, which is in turn based on IPCC’s recommendations.Our current policy trajectory puts us directly on track for widespread devastation and misery, all of which is likely familiar to anyone who has read a newspaper or watched the news at any point in the past few decades.

And so I can say this, with some degree of certitude: It’s total bullshit.

It Takes Selflessness to Save the Planet

What’s most distressing about this dynamic is that even though every major developed country pays lip service to “climate hope” or similar greenwashing mantras, in the background these same countries are quietly jockeying for primacy on soon-to-be-viable polar shipping routes, forestalling immigration by climate refugees, or taking steps to secure freshwater and other resources in anticipation of a hotter, drier future.For every paean to climate optimism by leaders, there are multiple subtle signals that countries actually expect to fail at preventing climate chaos. Canada, which terms itself “a world leader in the fight against climate change” has begun deploying military rangers to lay the groundwork for shipping lanes in the Arctic. Norway, with something of an environmental halo for its “green” policies and well-regarded role in international environmental diplomacy, is currently accelerating its pace of oil well exploration and is on track to drill more oil wells than ever before. Germany, a leader among major industrialized nations for its share of renewable energy is tightening immigration policy to decrease the numbers of asylum seekers allowed in the country (both climate-driven and otherwise). New Zealand, a darling of the international set for its “clean, green” image and 84 percent renewable electricity has been fighting to prevent an expected upwelling of Pacific Island climate refugees from seeking asylum, arguing there are “no legally binding regional conventions or treaties that prescribe obligations for developed countries towards Pacific Island neighbours in the climate change context.”

Our current policy trajectory puts us directly on track for widespread devastation and misery.

Why the Paris Agreement Failed: A United Front Against Responsibility

The discrepancy between countries’ words and actions takes on special significance when these actions serve to force others to pay the cost of climate inaction. This discrepancy between word and deed is a bad faith version of the free-rider problem. Virtually every country wants to avoid the consequences of climate change, but developed countries are apparently trying to virtue signal their way into everyone else carrying the water (often literally—China is hard at work re-engineering transboundary water flows in its favor).No amount of recycling or carpooling is going to surmount our multiple decades of inaction on climate change. No amount of lofty rhetoric or calls for comity is meaningful when we still don’t have binding international agreements, let alone carbon fee and dividend plans with border tax adjustments. Since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted in 1992, per capita CO2 emissions have increased by 17 percent.We’re not just failing to heal the world, we’re not even flattening the curve on climate change.Against this backdrop, references to sustainable futures by wealthy countries begin to seem like misdirection, intended to lull us into a false sense of security while the greatest tragedy of the commons in human history is allowed to reach its logical endpoint. Major industrialized nations sign (non-binding) declarations sanctifying territorial integrity, sovereignty, agreed upon international norms, development goals, decarbonization, sustainability—and then muster a dismal zero percent compliance rate with the Paris Agreement.

No amount of recycling or carpooling is going to surmount our multiple decades of inaction on climate change.

The Effectiveness of the Paris Agreement Comes Down to a Lack of Accountability

Our generation has been tasked with finding solutions to environmental catastrophes set in motion long ago. Everything in my experience suggests to me that the UN will likely not be up to the task of addressing climate change. No one is riding to our rescue. There are no adults in the room. We have no recourse. We will need to take direct action if we want to save the planet. Failing that, the cynic in me thinks the safest individual course is to take the lead of wealthy industrialized countries, and hope that conspicuously miming climate action will trick other people into making the sacrifices we’re not willing to make ourselves, while secretly planning for a hopeless future.Ivan Goncharov, in his novel, Oblomov, noted that “it's the trick of dishonest people to offer sacrifices that are not needed or cannot be made so as to avoid making those that are required.” International diplomacy around climate change mitigation and adaptation is suffused with precisely this variety of trickery. I have never in my life flown more than when I worked for a UN specialized agency on climate change programming, and multiple branches of the UN (including the one requiring me to fly around the world for meetings that could have easily been transacted online) don’t even bother offsetting their carbon emissions.This disregard is mirrored in the behavior of the diplomats and trade representatives who attend international climate change negotiations. I have personally seen delegates asleep in their seats at climate change meetings, and resource-constrained country delegates agitate for more widespread travel because it renders one eligible for a (relatively) generous daily service allowance. I don’t at all intend this as a lamentation about the edifice of international environmental diplomacy. Rather, I’m arguing in favor of actual diplomacy with teeth, that will result in common but differentiated responsibilities, tangible provisions to offset the loss and damage that vulnerable countries have suffered, and binding, enforceable climate mitigation agreements. Anything less amounts to avoiding the sacrifices that we actually require.

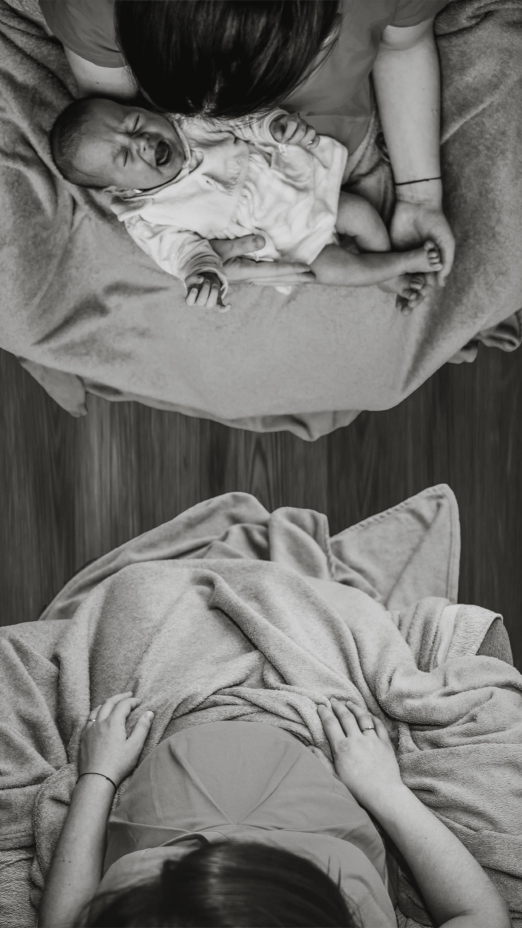

Birth Strike: Coming to Terms With Climate Grief

A family video of me taken when I was six years old shows me dutifully feeding my youngest brother via the bottle. My dad asks me how many kids I want to have when I’m older and, without skipping a beat, I say “Five.” He asks me how old I think I’ll be when I start having these five kids; I pause for a minute to consider before answering, “23.”Five kids—it is ludicrous to even think of at present. By my own timeline (and with reference to my mother’s reproductive schedule), I should have at least three kids in tow by now. But I don’t.I don’t know how to reconcile the climate change work that I do with what I consider my most innate and defining call: to be a mother.

I don’t know how to reconcile the climate change work that I do with what I consider my most innate and defining call: to be a mother.

How My Maternal Instinct Has Exacerbated My Climate Grief

Wanting to be a mother constitutes some of my earliest memories, such as holding my favorite dolls, putting balloons up my shirt and pretending I was pregnant, feeding my siblings and fighting with my sister for the right to push our baby brother in the stroller, taking my brother to my kindergarten class to proudly present him for show-and-tell.As I grew up and tried to tease apart how much of my desire to be a mother was just indoctrination and how much was actually instinctive, I had to admit to myself that I was secretly relieved when studies about apes and chimps showed that males and females showed the same evolutionary proclivities: many girls are drawn to dolls, many boys prefer wheeled toys.The bulk of my adult life has been working with a large intergovernmental environmental organization dedicated to finding solutions to seemingly intractable environmental problems. I work within the climate change team; as my knowledge of the climate and ecological crisis evolves, it doesn’t square easily with bringing more life into the world.Right now, I’m shocked over how the COVID-19 world lays bare every crack, every fissure, every social injustice and climate inequity. The world’s response to this pandemic illustrates, in some respects, that those who possess the fewest resources to deal with the virus will bear the worst consequences of the virus. For example, the poor, the uninsured, the migrant, the minimum wage worker—these are the people who are forced disproportionately to bear the negative consequences of the spread of COVID-19.And our climate future looms as even more dismal.Is a birth strike a sign of moral protest? Or a tacit acknowledgment of defeat? Is having a baby a defiant act of optimism? Or a hopelessly selfish and shortsighted choice?What is the balance between hope and realism? I draw inspiration from Angela Davis’ dictum: “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” Yet what act more radically transforms the world: a birth strike, or raising the next generation of climate warriors?

Yet what act more radically transforms the world: a birth strike, or raising the next generation of climate warriors?

Choosing Not to Have Kids Seems More Reasonable Than Ever, Now

As I grapple with this question, I consider how this question of whether or not to have kids was addressed in Meehan Crist’s recent article. She writes, “[Y]ou will feel—with rage, or sorrow, or relief—that it has been made for you. But the fantasy of choice quickly begins to dissipate when we acknowledge that the conditions for human flourishing are distributed so unevenly, and that, in an age of ecological catastrophe, we face a range of possible futures in which these conditions no longer reliably exist.”And this cognitive dissonance or disconnect takes on a new degree of dread as this pandemic seems to portend what the future might hold.In Crist’s article, she also narrates the moment when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez voiced the question that still seems very impolite and not politically correct “while speaking to her millions of Instagram followers via live stream: ‘Our planet is going to hit disaster if we don’t turn this ship around,’ she said, looking up from a chopping-board littered with squash peel. ‘There’s a scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult.’ Her hands fluttered to the hem of her sweater, then to the waistband of her trousers, which she absentmindedly adjusted. ‘And it does lead, I think, young people to have a legitimate question, you know, should…,’ she took a moment to get the wording right: ‘Is it OK to still have children?’”I think a lot about climate grief and how to deal with what this planet might look like in 30 years or 50 years, but I still can’t wrap my head around what that means for my reproductive future. And now I’m adding the overlay of pandemic grief as I grapple with this question. I recognize that a post-COVID-19 world—where we should make dramatic choices to right this ship and choose to redefine the new normal with nature at the core of our decision-making—may not be a livable one. As the current bailout is doubling down on oil and the future looks even more uncertain than before, maybe I need to put this question to bed: It feels like the future is already here.

How My Cat Taught Me to Respect Boundaries

When I was around seven or eight, my family brought home a female kitten named Tiger.My first memory of Tiger was watching her, hop from room to room, a playful ball of ginger and white fur.My second memory was watching Tiger dig her claws so deep into my brother's head that I could see the blood trickle down his temples.Tiger didn't like to be picked up.I knew this, my brother knew this, everyone knew this and yet he decided to do it anyway. And so, he was punished.Tiger spent her life explaining, in her way, how she did like it when you picked her up, sat too close or petted her too hard or too long. And she was good at it.Those who broke her rules were hit with a claw. Most got the message right away, but for those who needed reminding, Tiger was happy to oblige. Now, while I have known many strong females in my life, none could quite articulate the need to respect boundaries as well as Tiger.

Tiger didn't like to be picked up.

Co-Existing With Animals Made My Family Stronger

Even today, with all three of us fully grown men, whenever we bring up the topic of dangerous animals, we find ourselves reminded of Tiger—as we speak in soft worried tones, and rub at our old scars.She scared everyone.She scared people, she scared cats, she even scared the neighbor's dog: It was a Staffordshire Bull Terrier, squat and energetic, and I can still see the look of glee on its face as it chased her into my house and up the stairs. I also remember what happened when Tiger was halfway up the stairs, how she stopped suddenly, as if remembering, and how she turned and attacked.I can still hear it, the sudden yelp of surprise as Tiger sent a flurry of slashes across the eyes of the dog. Then he ran, with Tiger close behind, chasing him down the stairs, out into the street and, finally, into his home.And there he remained, bloody and terrified, with Tiger returning to the house, more or less fine, only now all of her hair stood on end. She must have spent a whole month sitting there, frowning like a ball of angry fluff.Everyone was scared, except for me, who as someone who liked to be left alone, found her attitude to be amazing. Nobody gained respect like Tiger.

She scared everyone.

Our Cat Made Me Feel Special

Another memory begins with me sitting on the couch, minding my own business. She was there, hopping up on the seat next to me. I was so scared that I can still feel it, the tightness in my chest as I sat there, holding my breath. And I remember the way she looked at me, neither angry or afraid, but what I saw in those big green eyes was curiosity, and that scared me more than anything. This woman had stared down parents and fought off dogs, so how could I not feel absolutely terrified as she sat there, trying to figure me out?Then, after a moment, as if some unsaid agreement had been made, she stepped over, onto my lap and curled up into a ball. This was, and still is, one of my greatest moments. To have someone who can make people listen, and I mean really listen, to have someone with that kind of power choose to sit with me? How could it not mean something?I've always known that beings like Tiger change the world, not through bullying, but by fighting back, by saying no when the bullies come and try and pick you up. But it wasn't until she sat on my lap that I realized that animals like Tiger are there to teach us. They just have to be there, to give you enough time to pay attention and to learn how to grow.Maybe you'll help people, too, but, in this world, that might not be as important as fighting for your own corner, for the right to choose where to sit, and when to stand. You have to fight no matter how big the dog is that chases you.Over the years Tiger and I developed a deep connection, with neither one trying to control the other. And while I can admit that a cat is a funny example, I have to say that no other creature has changed my world, so deeply, so personally, so much as she has—a little playful ball of ginger and white fur that left her mark on the world, one scratch at a time.

I'm a Music Professional Out of Work Due to COVID-19

By the time September rolled around, I knew the live music industry was suffering. Of course, it was. Venues had been closed since the pandemic hit six months prior, and it would be a long spell still before they could safely reopen. Luckily, the arts sector had qualified for the furlough scheme which meant my job as a digital content coordinator for one of the biggest chains of music venues across the U.K. had been safe. I, like many of my colleagues and industry professionals around the country, had taken a salary cut, but we were assured early on that it wouldn’t become much more serious than a 20 percent reduction. If I had a penny for every time someone said it would be alright, I probably wouldn’t be so panicked about my dwindling funds right now as I sit reading job rejection after job rejection.As the months stretched and the projected opening dates kept getting pushed back, whispers of redundancies began circling like sharks. But even near the end, there were assurances that balance sheets looked good. We were “fine,” although I can’t say the pitched voice in which they told us that was entirely believable, but naivete stepped in to push any doubt away. It turned out that I was the chum. Just days after my birthday in September, we got the call that I, along with most of my office, was being made redundant. Suddenly things weren’t so fine.

Most of all, I was angry at the government's lukewarm approach to putting lockdown measures in place.

The Music Industry Was Blindsided by COVID

I felt betrayed by the false sense of security my employer had lulled me into. Why didn't they just tell us we had to prepare for the worst? Maybe that was my way of denying the situation. Maybe it wasn’t. It didn’t matter because that first stage of grief didn’t last long before giving away to anger. I was angry at the government for not stepping in to offer venues the funding they were literally petitioning for, angry at people for not taking COVID seriously, for not wearing their masks, for not caring that people’s livelihoods were in the balance as they partied in Soho during a pandemic. Hell, I was angry at myself for not foreseeing this outcome, and for not being more proactive. Most of all, I was angry at the government's lukewarm approach to putting lockdown measures in place. I kept telling myself that if Boris Johnson had made the call even a week earlier, it could’ve changed the timeline of this year massively. For all my rage, I still couldn’t alter reality, and as hard as I tried to accept the situation, I failed to swerve the panic that inevitably followed. I wasn’t born in the U.K. and didn’t go to university with a group of mates, which meant there was no little book of contacts who could hook me up with another job in music. I was on my own, and the fear that I would lose everything I’d worked for and never get it back was rising.

The insinuation that our jobs are unviable, as if they are somehow less than worthy of saving, is insulting.

I’m Not Only Losing a Job, but All of the Work It Took to Break Into Music

The music industry is a tough one to crack. It had taken me five years of voluntarily writing concert and album reviews for any online publication that’d take me before I finally bagged my dream job. Even with years of writing experience, it was my collection of internet skills that secured me the position, and to keep it I had to keep leveling up. I wrote blog posts, interviewed bands, dabbled in image creation, created social content, took minutes at meetings, built weekly emails, reported on the results, set up live music events and dealt with venue requests. I was as much a PA as a writer, an account manager as a CRM executive, and yet, my skills weren’t able to save me from redundancy because the company I worked for couldn’t open their doors despite still paying daily operating costs. Without any aid in sight, and with the end of the furlough scheme looming, they had two options: keep their staff and sink, or lay everyone off for a chance at survival. What would you have done?Our bosses were backed into a corner by a government which has consequently seemed unfazed by the sinking arts sector. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak showed a blasé attitude by recommending people retrain and adapt to this new reality of not working in the creative industry because it’s a “fresh opportunity.” Well here’s the thing, Mr. Sunak: I don’t want to adapt and I certainly don’t need to retrain, because I already possess a multitude of skills I have spent most of my adult life acquiring, and the insinuation that our jobs are unviable, as if they are somehow less than worthy of saving, is insulting. I’m not disputing that these are difficult times for everyone, but there’s common sense in giving a boost to a sector that’s hurting because it’s unable to trade with socially distancing measures in place—especially when it’s contributing around ten billion pounds to the U.K. economy per year. Call it an investment.Days after my final payout popped into my bank account, heavily taxed (as though they haven’t taken enough), the government announced a furlough extension that could’ve potentially saved us. It reeked of calculation. Why had they waited for tens of thousands of people to lose their jobs before making the call? I’ll tell you why: fewer employees means less for them to pay out. Cynical, possibly, but it’s hard to not feel let down.

Music Is More Than a Job to Me—It’s My Life

So here I sit and as I’m writing this, I yearn for a new opportunity in an industry I love with every fiber of my being, but I’m realistic enough to recognize how slim my chances are of finding one. With very few positions available in what is now a field saturated by unemployment, every application is a fight and each rejection pushes me a little further away from where I want to be. It seems, at this point at least, that starting again will become necessary, even if it hurts to imagine myself doing anything else. The funny thing is, I could learn to accept it if at least live music survives. And yet as days turn into months, even that seems unlikely. That’s the true devastation. Music is synonymous with therapy. It feeds the soul, guides us through tough times, allows us to grieve, brings us joy, creates space for us and it’s often where we find our people. Something so vital to the human condition should be preserved, shouldn’t it? With the way it’s going at the moment, I’m not sure the live music industry will survive. I do know that this country would be less without it, and so I’m left heartbroken, angry, anxious and deflated knowing that the people with the power to turn it around are the same ones who view the ashes of this cultural Pompeii as a “new opportunity.”

Emotional Abuse at Work Wasn't Worth Working With Celebrities

As a starry-eyed Midwesterner growing up, I was a cliché. I dreamt of working in Hollywood as a writer or director. It was going to happen for me. It had to.But towards the end of high school and into college, my focus shifted. I liked the idea of journalism more, and eventually majored in public relations (something that nobody dreams about). I graduated a decade ago, penniless and desperate for work upon moving to New York. But instead of applying for marketing and PR gigs, something else fell into my lap: I was offered a position at an A-list Hollywood talent management company. It came from a tip by a friend working in casting. The industry found me after all—and what better way to combine PR, TV and movies than to help manage actors’ careers?

The Signs of a Toxic Work Environment Were Right in Front of Me

While my peers took boring entry-level marketing gigs for $40,000 or more, I accepted this assistant position to the tune of $22,000 per year. I’m not even sure if that wage was legal. I was fortunate to find a rent-stabilized apartment, and I was also lucky that there was a Subway across the street from work—as in, a Subway sandwich shop, not the MTA. I survived on their $5 footlongs for lunch and dinner every damn day.The low pay wasn’t the hardest part of the job. It was the fact that they made me change my name. I’m not kidding. I had only one interview (which took place two hours after I was referred, and I started the next day…red flag?). The head agent told me I would need to change my name. She’d recently had an assistant with my name—and that person was still working in the office. “It will be too confusing if you answer the phone and say ‘Gold Management, hello this is Mallory,’” she told me. “They’ll think you’re the other Mallory, and I need them to know you’re you, that you’re new and that they need to start over with you, instead of whatever stuff the other Mallory already knows as an institution. So, what’s your new name?”I was floored. And I had to pick a name on the spot. “Well, uh, how about my middle name, Tamara?”So Tamara I became. At least to all the casting directors and Oscar winners and head managers. The other assistants opted for a less flattering take: Tammy. (No offense if your name is Tammy. It’s just that they said it with such diminution.)

The low pay wasn’t the hardest part of the job. It was that they made me change my name.

Textbook Examples of Emotional Abuse in the Workplace

For that grand $22,000, Tamara/Tammy had to arrive at work at 9 a.m. every day and set up the entire office, making sure pens had ink, printers had paper, actors had call sheets and pilot scripts, and that the coffee maker had K-Cups. I was usually a few minutes late, since the managers wouldn’t roll in until late morning (in time for their L.A. clients and counterparts to get online). But every morning, the other Mallory would beat me to work, and she would remind me how shitty of an assistant I was for being three minutes tardy. This same Mallory would yell into my ear whenever I answered the phones (my primary task since the phones were off the hook and you can’t leave casting directors and A-listers unanswered or on hold). “You’re being too polite, Tammy,” Mallory would bark. “Don’t tell Lauren Orsenwells how your day is going, she’s the busiest casting director in the industry, she doesn’t fucking care.”“Lauren Orsenwells asked how my day is going. She always asks. I wouldn’t tell her if she didn’t ask,” I would snap back. Mallory would only quiet down if I snapped back. If I acted too small or too polite, she would only prey more. She fed off perceived weakness. That was difficult for me—I am overly polite and Midwestern. It’s not a weakness. It’s proper manners. Lauren Orsenwells seemed to enjoy that I was answering the calls. As did everyone, probably because I was polite to them.

I Experienced All Types of Emotional Abuse

The Starbucks downstairs knew my order whenever I walked in. Or rather, they knew my boss’ order whenever I walked in. It was something ridiculous, like a “decaf iced this or that, one pump of this, extra foam, and a hand-stirred stevia”—but only hand stirred by me, not by the Starbucks staff. At least she trusted me for that. But in between the moments of trust, there was a piling-on of ridicule. “How do you not know what all of our clients sound like? If they call, you are expected to know who it is. Memorize their phone numbers.” Or, “You transfer calls way too slow. I need you to transfer them in half a second, nothing more.” Or, “You need to rebook [up-and-comer’s] casting session today. You shouldn’t book her in the morning like you did, because she has a bad morning voice. She needs a few hours to find her proper voice every day.” Or, “Why isn’t [A-lister’s] private driver outside her house? You can’t leave her waiting in her lobby. That’s so embarrassing for her.” (In that last instance, the driver was stuck in traffic. I’m sorry, but Tamara can’t turn red lights green. Miss Oscar Nominee is just going to have to endure the utter humiliation of standing in her own building’s lobby for five more minutes.)My tenure overlapped TV pilot season, wherein all the actors run around L.A. and New York trying to book shows, some of them auditioning for dozens of roles. I remember the office discussing a young actor on their roster who was struggling to book any gigs. “Maybe he just doesn’t have what it takes. Or maybe he isn’t kissing enough casting director ass.” They lamented that he might have to find “a normal job” soon, since they planned to drop him from their client list. Someone chuckled that he was actually “the lucky one.” That stuck in my mind.

I’m not even sure if that was legal.

I Realized the Entertainment Industry Wasn’t for Me

Because we had to work NYC and L.A. hours, I would leave each night at 9 p.m. This was three hours after the managers left, leaving the three assistants to round out the L.A. hours and prepare scripts or casting clips, as well as order office supplies for the next day. The day usually ended with Mallory saying, “Tammy, you’re a great assistant,” and the head boss telling me I was the best assistant she had ever had. I learned quickly that this was how they ensnare you. It’s a day of berating, then high compliments at the end. One evening, I and another assistant (not Mallory) were the last two in the office. I asked him how long people had to be assistants before they got promoted. “Like six or eight years maybe,” he said. “And it’s worth it once you get there, the money is good. Six figures.” But at 25, with a $22,000 salary and some $40,000 in college and credit card debt, I knew I couldn’t endure six-to-eight more years. (This realization came a whopping two months into the job.)I also knew I couldn’t survive much longer because I started to dissociate. For those 12 hours in the office (or 11 hours and 57 minutes if you sourced Mallory), I was Tamara/Tammy. I let her take the berating, so that Mallory, my real self, could unplug as soon as I exited. Mallory was at peace for the 12 hours I wasn’t at work. I had a sense of humor. I had hobbies, though I barely had time to enjoy them. I had friends I could only see on the weekend. I just never had money to pay for anything. As for the weekdays, however, eight of those daily “Mallory hours” were spent sleeping. Two of them were spent commuting. I would eat most lunches and dinners at my desk, bless those $5 footlongs because otherwise dinners were cold lentils or plain oatmeal. Another hour was spent in the bathroom, getting ready in the morning or winding down before bed. With 11 hours wasted, I had just one hour a day to myself, to be myself. To empty out all of the verbal abuse and the low self-worth.

Recovering From Emotional Abuse at Work Was Easy

I couldn’t keep up with the rich kids who lived at home with their parents (or whose parents paid their rent) and had no bills. I couldn’t do it now, much less for six-to-eight more years. Suddenly, my friends’ boring advertising jobs seemed far less compromising. So I begged them for work, got an offer fairly quickly and took the first train out of Hollywood. It stings a little that some of my favorite actors knew me only as Tamara and not as Mallory. And it hurts to imagine the sliding door scenario wherein I worked in my dream industry. But that’s as much a fantasy as the original dream itself. I was fortunate to realize the sacrifice it requires—and the shit one must endure when there is far too much at stake. No prestige or title or pipedream is worth being treated as worthless as I felt in that position.I happily put Tamara to bed, and woke up from that silver-screen dream. Mallory (me!) has never been happier. I don’t care enough to check in on the other Mallory. But now that I think about her, I wonder whether or not she became a big-time manager. Enough time has passed, so she’s probably making six figures, if so. At the very least, she’s probably moved out of her parents’ house.While I didn’t quite have the chops to succeed in that environment, the other Mallory certainly did. And polite as I may be, that’s no high compliment from me.

Stand-Up Comedy Is Dead, Except for Rooftop Comedy in NYC

On March 14 of this year, as the coronavirus started to spread all over the East Coast, and a slow, methodic panic began to settle into the greater Brooklyn area where I lived, I was on stage at the Crystal Springs Resort in Hamburg, New Jersey, telling jokes about anal sex to middle-aged soccer moms drinking tea out of tiny, porcelain saucers. That was my last “normal” stand-up comedy show of 2020. One of the many reasons why stand-up comedy is so intoxicating is that much like 2020, you never actually know what’s going to happen, and you have to prepare and be on guard for the fact that literally anything can happen: chaotic talking, clanging dishes, unexpected music piping in from the ceiling, microphones breaking, ornery hecklers, happy hecklers, supportive hecklers, horny hecklers, patrons screaming drink orders across the room, sound systems short-circuiting, cappuccino makers that sound like NASCAR engines and, oh yeah, more hecklers. And what makes dealing with this alchemy of insanity even more challenging is that you can never predict what kind of response you will get from the audience. No matter how much you think you know, an audience will prove you wrong just as much as it will prove you right.

The Last Comedy Show I Did IRL

Right before I went on stage at the resort in Nowhere Fuck, New Jersey, I took one look out into the crowd and said to myself, “Well, this isn’t going to go well.” The show took place in a dimly lit, giant unused ballroom, (venues of this stature are categorically terrible for comedy), and making matters worse, it was impossible to find and completely tucked away in the corner of an even bigger and more sprawling resort. Think The Shining with a sick hot tub.We were also competing with a professional magician, who just so happened to be performing at the same time in a nearby, extremely well-lit and easy-to-find ballroom in the hotel. Spoiler alert: In the comedian vs. magician same-night show standoff, magicians win 90 percent of the time, especially with the clientele at a hotel in Nowhere Fuck, New Jersey. And oh, by the way, there were also some minor rumblings of a global pandemic coming our way.To add even further drama to the mix, I brought Emily, a woman I had just met on Hinge a few weeks prior, as my date. We had been out a few times to some slick Brooklyn bars and restaurants and I thought it was time to up the ante for our third date. “Hey, you wanna come out and watch me beg for stranger’s attention in a deserted golf resort filled with magician-hungry tourists?” And as a massive credit to Hinge and dating app matching accuracy, she said, “Sure!”

Spoiler alert: In the comedian vs. magician same-night show standoff, magicians win 90 percent of the time.

The World Still Needs Stand-Up Comedy

The host went up and did 15 minutes on smoking weed and video games to a very tepid but expected response. Then it was my turn. As I approached the stage, I glared out at the 13 or so 60-year old women, scattered throughout the cavernous ballroom, all of whom just so happened to look like my mom, and winced to myself, “Fuckin’ magicians.” I go onstage and open with my standard jokes about having a dad bod and getting older and the crowd is giving me a light smattering of laughter. The best outcome for a comedian is a riot fest of boisterous laughter, the worst outcome is silence, especially dead silence. The kind of silence where you can hear yourself think so much that your mind actually travels back to a time when your parents told you to go to grad school. As a comedian, nothing is worse than silence. So I’ll gladly take a few charity chuckles.I then launch into my joke on modern dating and relationship bases and even before I start the joke, I’m convinced it’s a huge mistake. “These women are all married and probably think ‘sex bases’ is the name of a new boyband,” I thought. I initially got a lukewarm response on my joke but it wasn’t until I uttered the word “anal” that the crowd completely erupted. And I mean a Def Comedy Jam meets The Golden Girls-style eruption of laughs. I was floored and shocked and thought, “Even with everything going on in the world and in this room, people are still laughing.”

The Future of Comedy and Humanity Share the Same Philosophy

In Dave Chappelle’s November 19 appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast, they ended with a philosophical discussion about the implications of COVID-19 on society. And the two comedy icons basically came to the same conclusion about life in a pandemic: “You find a way.” And “finding a way,” is exactly what the New York City comedy scene has managed to do since the onslaught of the coronavirus pandemic. In mid-to-late March, all comedy clubs, bar shows, rock venues and arenas announced the cancellation of all comedy shows. I personally had several dates on my performance calendar completely wiped out. The Upright Citizens Brigade Theater, the comedy Mecca and central pipeline for famous comedic talent, announced its closure on April 21. Indie stand-up venue the Creek and the Cave soon followed suit, announcing its closure in mid-November. But despite the pandemic’s massive blow to the live stand-up and improv comedy world, comedians quickly adjusted, starting a series of virtual shows via Zoom and Instagram. In late March, I performed on an Instagram Live show for the Stand Comedy Club with anywhere from 20 to 30 fans logging on to see me perform from my uncle’s toy room in Scotch Plains, New Jersey. Brooklyn comedian Aaron Kominos-Smith continued the tradition of his weekly stand-up show at the Postmark Cafe in Park Slope, Brooklyn, by hosting it live on Zoom at 8 p.m. every Friday. Kominos estimates the weekly show gets up to 100 views per week, an impressive number considering the live show would net anywhere between 20 and 40 attendees.“It’s amazing that we can have comedians from across the world all performing for an audience that couldn’t otherwise make it to a little coffee shop in Brooklyn. We try to keep that same vibe and have a lot of repeat audiences who chat before the show, almost as if we really were in a coffee shop right before a show,” Kominos said. Manhattan-based comedian Lance Weiss decided to put his live stand-up comedy dates on pause to focus on performing “Zoom bombs,” where Weiss would crash corporate Zoom meetings to bring in some much-needed humor to spice up the endless cycle of dull and dreary online work meetings.

But despite myriad fresh obstacles, live comedy in New York has persisted quite successfully.

Rooftop Comedy Shows Epitomize the Spirit of NYC Comedy

Once the weather began to turn warmer in mid-spring, comedians started producing their shows in outdoor environments and venues. Newark comedian Justin Williams hosted a few shows at outdoor venues in his city and was thrilled with the response. “The vibe was great,” he said. “Both of the shows were sold out and people in Newark were happy to see things return for a brief moment.”As many comedy clubs continued to struggle, moving shows to the front of their establishment or, like the Stand-Up New York Comedy Club, producing events in Central Park, comedian Sam Morrison found that outdoor post-COVID comedy was ripe with a whole new slew of challenges. “Comedy was too easy for me. Paying audience members in buildings? No, no, no. Give me six strangers spread out over 40 yards and a Sheepadoodle barking over us all. That’s real comedy.” Comedian Tyler Fischer described the impossible challenge of making several spread-out strangers in masks chuckle. “Doing shows during COVID was like going back to being a brand new comedian when you really didn’t know what was funny. That’s because most people have masks on so you aren’t able to read their faces or see if they are smiling. You have no clue if they’re enjoying you. That’s how most Tinder dates are for me so I was kind of used to it,” Fischer said.

Maybe Stand-Up Comedy Isn’t Dead, After All

But despite myriad fresh obstacles, live comedy in New York has persisted quite successfully. New York Comedy Club has seamlessly moved its performances to the Midtown Penthouse in Gramercy, and the Hudson Penthouse at the Hudson Yards. The Tiny Cupboard, an artsy rooftop comedy club located in Bushwick, Brooklyn, is producing as many as 15 shows each week. The alternative space is an indie comedy fan’s dream with admission costs ranging from free to ten bucks a show. While many comedians are appreciating the fresh opportunities for unconventional stage time, they still long for the days of jam-packed, audiences roaring in laughter. “Comedy is the opposite of COVID,” Fischer said. “You want to infect everyone with laughter and have it spread to as many humans as possible. It has been rough for sure. But, hey, it got me out of the house,” And maybe the need to get out of the house is all it took for comedians to find a way to continue to bring laughter to the world however damaged it might be. I just hope my first “normal” show back isn’t in front of a bunch of people looking for a magician.

The Record Industry Thrives on the Exploitation of Young Rappers

I wanted to work in the music industry since I was 12, when I first saw Snoop’s video for “What’s My Name,” where he turns into a dog and bites the old man and jumps out the window. My dad hated that song, so it was really formative for me. I was living in a third- or fourth-tier city, so I was discovering music from the outside. Skate videos educated me on music until 1999, maybe 2000, when somebody showed me Napster and explained what an MP3 was. Then I picked up a copy of The Source and there was this industry section in the back, and I saw a picture of the guy in a convertible talking about his job in A&R. At that point I didn’t even know what “A&R” meant, but I was like, “That sounds like a sick job. I want to do that.”Eventually, I moved to L.A. with the goal of finding a rapper to develop into the next Kendrick or Chance. This one guy popped up on my timeline for some reason, and it was like half a song on YouTube but I thought it was really awesome. He was just really, really smart, and was talking about things differently than I had heard in the past. We spun up two mixtapes, spent $150 on a video, and then that video ended up doing millions of streams in a couple of weeks. We had every major label trying to sign us at this point. We chose one of them, and that’s when the shit hit the fan, in such a serious way.

How a Rapper Gets Signed in 2020

There’s a path that most young rappers follow to get to a big record deal. Typically it starts with somebody who’s either good at freestyling or good at singing. That person’s work or notoriety, or their name, gets in the ears of somebody with studios. In a lot of the communities these rappers are coming from, people buy studios to diversify and legitimize revenue that they make through other means. Regardless of how they acquire the studio, normally they will invite somebody in and say, “Hey, you’re really talented. You can use the studio free for however long.” Or they’ll say, “There’s no studio fee, but you gotta sign to us as a production company. You can use our producers and you can use our engineers.” Those deals are where it gets really spicy. They can be egregious, and hard to get out of. They’re nuanced, but essentially at the end of the day they look like, “50 percent of every dollar you make goes to me, and whatever’s left goes to the label.” So when they arrange a label deal for the artist, they already own half the pie. A lot of the biggest rappers in the game are still stuck in deals like this that they signed at the beginning of their careers. If you get an artist to sign one early, they’re pretty much bulletproof. Being on the profitable side of them is how you get extremely rich in rap music. And they do provide a lot of value—a lot of people’s first mixtapes wouldn't be made without these people. Hence they wouldn't get the ear of the streets, they wouldn’t get the radio DJs and the mix show DJs playing them. But from then on they’re locked in. A lot of people don't really blow up on Soundcloud first. A lot of artists are incubated from a very early stage, to the point where they kinda can't fail. You're almost guaranteed to get to a certain level if you're signed to the right producer. That doesn’t mean you’re making any money. The label negotiates explicitly with the person that has the furnishing agreement, the production deal. So while they’re incentivized to get the best deal, you don’t have any say in it. If you hated your A&R, you wouldn't have a choice, you're just doing this. Or if you have any moral qualms with other music on the label, or if you just don’t think it’s the right fit, you don’t have a choice.

Spotify is a whole other beast.

Labels Have Money to Spend—as Long as You Stay on Their Good Side

Typically, at this point, the label teams step in and, either you’ve already got a single that’s doing really well and they want to amplify it, or they say, “Here’s a very small budget. Come back to us when you have a hit.” And then it’s up to you and the people around you, often your producers. A lot of people stagnate and stay in that zone. And if you get stuck there, they can’t really get out. They have really no agency, and they’re kinda living the same life they were living before, but they can't put music out. Because, again, everything has to be mutually approved by the producers and label.So say you do manage to get a great single going. The next step is radio, where normally you start out at what’s called “mix shows,” which are certain time slots on urban radio where they test out new records, and the label gives you a small “promotion budget.” It’s very transparent that you’re paying to get the song played. (And it’s not just rap. You have to pay for play in rock and dance music and all kinds of other things.) Payola is absolutely legitimately still a thing. It’s just become one of those open secrets in the music industry.If you can't get the single off the ground in mix shows, it’s very seldom it’s going to move beyond that. But if it’s undeniable, like if it’s a fucking smash, you’ll start getting adds on urban radio. At that point, they do what’s called “research,” where a company randomly calls people in the area, asks them if they’ve heard the song and to rate it on a scale of one to ten. You literally use a phone to say like, “Yes, Post Malone is a six.” And based on the data that comes back from these insanely outdated polling methods that determine the future of your single. It literally makes zero fucking sense. It’s so fucking weird and completely archaic.But say your song does well, the research comes back semi-positive and it’s picking up in New York, Mid-Atlantic, down South, Texas, California—then you have to go to do radio promo. In New York, for example, we did one of the big shows, and the DJ is like, “Come by the club tonight, we’re gonna play your song.” This means we go to the strip club, and the DJ plays our song. But I’m not spending money at a strip club and neither is my artist, so our label guy goes to the ATM and brings us back $2K in cash. We just throw it at the strippers and walk away, because the club needs us to pay the DJ at the club, instead of the radio station where he also works. It’s just so transparent and fucking weird. And then you’ll do that six nights a week for weeks at a time, all up and down the coast. It’s a nightmare, but that’s what it takes to get a record played. If you can land your song in the territory of the Hot 100, you're pretty much set for the next couple of singles at least. You’d have to fall off pretty hard because the label at least sees there’s some traction and you’re worth investing in. But if you don't get that first one out, and they spent $150K on radio promo, and the record doesn’t break the Top Ten, and they spent $150K on radio promo, you’re very hard-pressed to get that opportunity again.And then Spotify is a whole other beast. It drives a lot of interest from the labels because they make more money from Spotify than they do from radio, for sure. But it’s such a black box, as opposed to radio, where you very clearly say, “Here, I am paying you to play the record.” Spotify basically decides what becomes a hit and what doesn’t. There’s definitely payola going on there too. Certain people at Spotify get really good Lakers seats (like, I've actually been in the suites with Spotify people). It’s really well-guarded, and I’ve never really experienced the payola side of it, but it very much exists. Absolutely. The label can circumvent that framework a little bit, if they really want to, especially because Universal owns a chunk of Spotify. So sometimes there is a magic bullet that can be fired, but it’s super rare.

What Happens to Rappers Who Don’t Make the Cut

If you don’t get Spotify playlisting and you don’t have a single, then your album is fundamentally worthless, and you’re starting from the beginning, with no budget to get you back on track. People who wind up there get jobs, or they sell drugs. They put money in their pocket somehow. I manage an artist right now and she was looking at one of the production deals we talked about and she was like, “I’m never signing that. I’d rather go be a stripper again. My kid’s not gonna starve.” So that’s kind of what happens. They are just people who had this weird fling with a major label and then they go back to their lives.Some may even wind up owing the label money on their deal. When you sign with a record label, typically there’s an advance attached. The advance means they put some money in your pocket to be able to sustain yourself while you work on the album. What’s not clear to a lot of people is that you have to pay that back, based on the split of the record deal. The label takes their side of the split, and you have to pay back the advance with your side. So say you’re in a deal with the label making 75 percent and you making 25. Whatever money comes in off your music, they’ll get paid back first, and then you start using your 25 percent to pay back the $100K or whatever that you got as an advance. And even if you do recoup, and they made all of that money, you still never own your master recordings. Essentially it’s like taking an insanely high-interest rate on a loan to buy a house, paying it off, and then you still don’t own it. But that rarely ever happens. Only about five percent of artists recoup, and I’m sure you can name those artists on two hands.

It’s a problematic system and I think Western capitalism will always dictate that it behaves this way.

Exploitation in the Music Industry Is a Systemic Issue

I’ve since experienced things at major labels with my other clients that are actually beneficial and positive. It’s about individuals. But at the same time, if you drill down into it, all of these companies are exactly the same. It’s not even these people, as much as it is their parent companies: the Carlisle Group, BlackRock or whatever it is. All of those companies are the ones that are ultimately benefiting from the talent of young people. These companies go to artists who are coming from lack of means, and they dangle checks in front of them and they invest in assets that they get at bargain-basement prices, and then leverage and eventually sell off. It’s just like private equity.It’s a problematic system and I think Western capitalism will always dictate that it behaves this way. It’s win-lose by design. There’s a universally acknowledged idea that publicly traded companies have no obligation other than to return as much value to its shareholders as possible. And that will always be to the detriment of ancillary aspects of the business, whether that be environmental fallout from fracking, or starting a coup in Bolivia so you can get your hands on more lithium to make batteries for your electric cars, or chewing up and spitting out promising young artists. It’s not even the fault of the individual participants. They don’t realize that these systems can change. They think, "I’m a good guy, and I’ll perform in this fucked up system in the best way I can." There’s a certain purity in the music industry—if any of us just wanted to get rich, finance isn’t that complicated. We could be at hedge funds if we wanted. But we do it for the passion. We love people, love storytelling, love to provide opportunities for people who wouldn't otherwise have them. But until we can build something completely different, the best anybody within the system can be is less evil.

I'm an EDM DJ: EDM Culture Needs to Change

I grew up in Chicago, listening to Chicago house music. My initial introduction to electronic music was through cookouts at my grandmother's grandma’s house where my uncles and my older cousins would play cassette mixtapes of the stuff that they were hearing in the clubs. I’d never heard anything like it. That’s what got me started DJing when I was in high school.Eventually, after years of spinning underground parties, I ended up part of the second wave of EDM in America, playing some of the biggest festivals in the country. I thought that shit was corny, but I was just really trying to fuck up the system. I was always like this outsider who just came in to go on stage and be like, “Fuck you, fuck this festival, fuck your mom, here’s a bunch of fucking bangers for 30 minutes.” I’d make $100K in an hour and then I’d get on the plane and go home.

Black people get the short end of the stick in everything.

EDM Needs to Recognize Its Black Roots

House music is Black music, or at least it has Black origins. EDM is its own genre that was cultivated in Europe. Starting with the first dubstep wave in America (e.g., Skrillex) and all the music that was happening around that, like progressive house and big room, it was all white music, made by white artists for a white audience, although it was definitely inspired by the music that Black artists were making. If you talk to those producers, they know all the shit their stuff is coming from. But if you just isolate the genre EDM, especially in America, it’s as white as country music. These kids that found it thought the genre had just appeared from out of nowhere, and they were the first wave of fans. They don’t even know about its history, let alone about its Black history.It’s not like EDM is maliciously being like, “Yo, fuck Black people, we’re not trying to support Black artists.” It’s sort of just in general following the guidelines of everything in the world. Black people get the short end of the stick in everything. And white kids have access to so much shit. There’s definitely a paywall when it comes to EDM. It’s a privileged art. You have to have a laptop, software, audio gear. It’s the same as how there’s not a lot of great Black skiers, because to go to a ski resort you have to have $1,000 worth of equipment and $500 to spend on a couple of days on the hill.

It’s Not Just Race—It’s About Class Too

Even more so than race, EDM is a class thing. A lot of the people that are in this come from means. There are so many artists in EDM that I met whose parents are doctors or lawyers. It’s the kind of thing where if you as an investigative journalist were to turn over all the stones you’d probably be like, “Holy shit, Tiësto’s dad invented Velcro!” They have a lot of money, they have a lot of time, and they have no pressure to succeed in it. And that’s something I’ve felt more so than anything, more than someone coming at me and being blatantly racist, it was more just being in rooms with people who were heirs to millions of dollars, who totally didn't need to succeed at music. They had no pressure on them whatsoever to do anything, and they were like, “Okay, I guess I’ll do this.” Meanwhile, I’m fucking hungry, and I’m like, “I gotta pay rent, so let’s play this shitty festival.” But, at the same time as I’m saying, there’s just so many fans and so much content and so much shit out there, I can say this: I can scream it from the rooftops, and it just goes over 99 percent of the people’s heads. Will they ever acknowledge it? Yeah, some will. But they need all the bigger artists to say it. It doesn’t need to be just Black artists. White supremacy is a white issue, for white people to figure out. So it shouldn’t be a burden for Black artists and Black people to even have to come forward and say this. It should be Diplo, it should be Dillon Francis, it should be Tiësto, and Deadmau5, Marshmello, all these white dudes to come out and say, “This is the definition of this music, respect needs to be given to X, Y, and Z DJs who laid the groundwork for the genre that I make.” But that’s not gonna happen. That’s just not.

Electronic music had started a nosedive around 2016, and I felt like this year we were gonna get some really cool shit. COVID tamped all that down.

How Can EDM Culture Fix Itself?

I don’t want to put this on the fans, like, “You can't enjoy this unless…” But, as an active participant in this genre of music, I have made it a part of my job to help educate kids on the origins of dance music. And at this moment in time, with the massive reckoning America is having with race, and the fact that it’s part of the conversation, I felt like it was a really good moment to speak out and say, okay, a lot of these artists that started the genres that you listen to, and that a lot of these white artists are benefiting from and profiting on, they’re Black artists. I post links on my socials to donate to different GoFundMes or whatever, and I’ll actually be able to track through back-end data to see that a bunch of people clicked through. That’s awesome, but also at the same time, it’s a short-lived thing and has already sort of fizzled out. Now EDM is just back to being white music for rich white kids. You see that too with all the other brands. During the protests in June, it was like Black History Month all over again with all the Black people on their social feeds. And then it went back to all-white models, all-white actors and actresses, all that shit.I felt as if 2020 was gonna turn a corner for music. All music goes in waves: rock, electronic, whatever. Like right now rap is killing it. I felt like electronic music had started a nosedive around 2016, and I felt like this year we were gonna get some really cool shit. COVID tamped all that down. It shut down all the venues. Any of the festivals the festival promoters that weren’t huge conglomerates already were then absorbed by the ones that were. And we’re gonna get another four to ten years of regurgitated shit. But the upside to it, the optimistic side to it, is the more commercial and shitty and boring that music gets, the better the rebound. The pendulum swings. It’s gonna be over here in commercial land a little longer or further than we thought, but it’s gonna go back in the craziest way. Hopefully a few years from now, we will have a big “fuck you” to this moment.

Watching Trashy Reality TV Got Me Through a Friend's Death

Imagine you’re at a party, half an hour deep into a meaningful conversation with your male friend. Across the room, someone calls your name and your attention is momentarily snatched away. Upon turning to resume the conversation, you discover he’s vanished. Perhaps he’s outside having a smoke, or seized the opportunity to empty his bladder. Nonetheless, the sensation is unnerving, disconcerting. Someone you were so sure was just there—laughing, sipping a beer, listening attentively—slipped away without your knowledge. You can still feel the warmth of his body, like a phantom limb. This is what it’s like to lose a friend in your 20s. My friend, we’ll call him Ed, was a fucking hoot. Not only that, he was extremely nice, too. Always had time for everyone. And not half-bad looking. I know it’s incredibly cliché to drown the dead in praise, but I struggle to think of something negative to say about Ed. He just had one pretty damning fault: a substance abuse problem. The combination of this and a losing battle with his mental health is what eventually led to his death. He was 22.Wrapping your head around someone’s passing is an obstacle made even harder to surmount when you lived together. Ed— along with me and a group of 60 or so other young people—was living in an Australian farm town called Ayr, home to ample aubergine harvests, sugar cane fields and the odd venomous brown snake. Surrounded in every direction by vast stretches of flat, empty road or fields of farmland, there was very little to do, which drew our little community of backpackers even closer. Shortly after Ed died, a number of our friends left the hostel. Through a strange coincidence, the end of these friends’ jobs coincided with Ed’s passing, meaning much of our friendship group loaded up their enormous bags and drove down the sprawling Bruce Highway towards Sydney. Those who remained were left to ruminate on our friend’s death while being simultaneously reminded of his life, his old bunk just a stone’s throw from ours. Two days after his death, I started a new job packing mangoes into boxes, which were stacked high and loaded into enormous vans destined to markets and restaurants hundreds of miles away. I felt envious of those mangoes.

This is what it’s like to lose a friend.

Vanderpump Rules Became a Necessary Distraction

Reality TV has always been a coping mechanism for me during times of heightened emotional distress. When I’m caught in a riptide of anxiety and my body floods with cortisol, making sense of the world around me feels impossible. In these moments I crave something easy to digest and episodes of sugary reality TV slide down the gullet with ease. The good guys and bad guys are clearly defined. Each story arc has a neat beginning, middle and end.I knew I needed a distraction. Between the ache of grief, endless monotony of my working days, recent reduction in friends and long stretches of time spent with my own thoughts driving to and from the farm each morning, my brain yearned for comfort. And so I began self-soothing with reality TV, my old pacifier. I tried the Kardashians, but the family’s displays of wealth were too gauche. Watching anyone from my home country, the U.K., brought on a torrent of homesickness. Instead, I settled on Vanderpump Rules, an eight-season reality drama following the lives of restaurant employees in Los Angeles. Grief is a funny thing and I expect most of the bereft do not seek solace in TV like VPR. But to me, the show was magic. The premise is such: Lisa Vanderpump, the British brunette of Real Housewives of Beverly Hills fame, runs SUR Restaurant in West Hollywood. SUR stands for "Sexy Unique Restaurant," making the real title, “Sexy Unique Restaurant Restaurant,” which I suppose sets the tone. Our protagonists are wannabe actors, models and musicians whose shot at gratifying fame has probably passed. Instead, they’ve settled for tequila, attention and reality TV notoriety, fighting in the dingy alleyway behind SUR and throwing drinks over one another for our viewing pleasure.The tumultuous relationships between the cast are just familiar enough to be relatable but maintain a level of distance. Characters are at once loathed, loved, flawed, deluded, inspired and pitied. I downloaded the series to my phone and efficiently worked my way through each season on my commute—at breakfast, before bed and in the bathroom when talking to other people became too difficult.

Observing young people misuse alcohol soon after losing a friend to substance abuse might sound like torture, but it was cathartic.

Vanderpump Characters Prove Nothing Is Unforgivable

The first season sees Stassi, a smiling assassin with glossy blonde locks and the sinewy limbs of a top model, battle with Jax, her on-off, bad-boy boyfriend. It’s obvious from the get-go that their romance is toxic. Stassi seethes whenever Jax’s wandering eye falls on another woman, while he in turn stokes the problem by flirting with every living soul in sight. They fight. They cry. They make up, only to split in an even more spectacular fashion. In their orbit, a merry band of fellow model-bartenders dance around the fire, fanning the flames and throwing on their own self-sabotage, delusions and unhealthy relationships for kindling.The beauty of VPR is that you can never really root for a character because everyone’s behavior is equally rotten. But by the next breath, the worst individual is somehow redeemed. As I steamed through the series, watching my heroes’ and heroines’ faces become taught with Juvéderm filler, I realized there are no winners in the VPR universe. Everyone gets a drink thrown on them. It’s oddly cathartic.When the most shocking allegations—impregnating a prostitute and cheating on your girlfriend in Vegas; sleeping with your boyfriend’s best friend on an IKEA sofa as your partner sleeps in the next room—turn out to be true, the audience is titillated with horror. But the show taught me nothing is truly unforgivable. Each cast member gets their vindication story arc, their atrocities absorbed as part of the ebb and flow of life. Watching these people forgive one another and, more importantly, themselves made me wonder what it would take to lift some of the guilt I carried with me following Ed’s death.

Reality Shows Helped Me Escape My Grief

Observing young people misuse alcohol soon after losing a friend to substance abuse might sound like torture, but it was cathartic. There are few case studies better than SUR’s staff in examining the blurred lines around misuse of intoxicants—there’s a gray area between using and abusing. The VPR cast dips its toes into this undefined space more than once: We see it when Jax pounds eight shots at the bar for no reason, or when the cast sneaks wine under the table at breakfast, or whenever characters frequently debate what happened during a night of blackout drinking. The show is a lesson in why abuse is hard to recognize, and why it’s even harder to intervene, especially when you’re surrounded by other people who are preoccupied with their own inner demons.Of course, there’s an element of schadenfreude involved as we observe these aesthetically beautiful young things fight, fuck and fail at their respective singing and acting careers. Watching a man nearing 40 steal a pair of sunglasses just for kicks or two grown adults screaming over a bowl of pasta is in some way vindication. But it’s impossible not to watch the show and feel some level of empathy with the characters whose most vulnerable moments are immortalized on television. For me, getting lost in the drama—sharing their euphoric highs and devastating lows—was a welcome break from grief, absence and the unrelenting Australian heat.During quarantine, as COVID-19 anxieties swept over the world, I turned off the news and tuned back into VPR. Its original shock factor was gone, but I still slid into the fully immersive, chaotic VPR world like a warm old jacket. Naysayers often dismiss reality TV as harmful or frivolous, a piece of mottled chewing gum on society’s shoe. There’s some truth in this assessment but these shows hold up a dirty mirror to human behavior, forcing us to reflect and stare, while providing escapism when life becomes too hard. The real world can wait.

I Discovered My White Privilege as a Child Actor in Mexico

If acting can be considered a job, I got my first when I was just five years old. That’s not just a story I tell my children. At such a young age, I learned a lot: from the value of hard work and delayed gratification to the existence of a very real type of “white privilege.” Wait, a conservative talking about white privilege? It’s not what you think. Over the years, the more I pondered being an American-born kid living in Mexico, the more obvious it became. My child-acting career was successful thanks in part to white privilege. But it wasn’t the Marxist-inspired fraud known as “white privilege” that supposedly plagues the United States. Rather, it was a very real phenomenon in the Spanish-speaking country.

Wait, a conservative talking about white privilege? It’s not what you think.

Being a Child Actor Had Its Challenges

The hard work—and it was hard work, especially for a young child—provided valuable lessons. The hours were often grueling. Sometimes we would stay on set almost all night. The seemingly endless repetition was enough to drive a person mad. Why couldn’t I go play with my friends like normal kids? Even school would have been better than standing in the same place, repeating the same dumb lines, making the same dumb motions over and over and over again. And I hated school. There would supposedly be a reward someday. But my parents just took all my money and invested it in a fund, whatever that meant, promising me access when I turned 18. To a young child, waiting until 18 sounds like waiting for eternity. Another lesson learned: delayed gratification. By the time I got to be 18 and received my money, I wasn’t much more mature than when I was earning it. And so, naturally, I spent it on drugs, parties and road trips. Occasionally there would some be instant gratification. One time, for example, my brother and I did a commercial for chips featuring “tazos”—a Mexican version of Pogs that came inside bags of chips. The team let us keep a whole suitcase full. Now that was cool! All the kids at school were so jealous. Suddenly, my brother and I were the tazo masters, carrying at least one of almost every version made.

I Experienced the Good and Bad of the Entertainment Industry

At eight years old, I was hired to act in a commercial for a new movie about fires set by Saddam Hussein. Basically, the ad showed a cake with “trick” candles that were impossible to blow out, right in front of me. The commercial ended up becoming ubiquitous. Anybody who watched TV saw it and saw it again. I learned how cruel some people could be—especially kids. At school, some of them would tease me. “You are so pathetic, you can’t even blow out some little candles,” they would laugh. My cheeks would turn bright red and I wished I could just hide.There was a flip side to that lesson, too. One of the projects I worked on was 1996’s Romeo + Juliet, much of which was filmed in Mexico City. I’ll never forget sitting next to a young Leonardo DiCaprio at a beautiful cathedral where he entertained me and my brother for hours on end with fart jokes. Yes, seriously. “Pffrrt.” He’d squinch his lips together and then look at us. “Hey, what was that? Who did that?!” We keeled over laughing and had a great time before finally going back to our personal trailer to relax for a while. Not really knowing who he was, my mom decided to snap a few photos of us standing next to Leo. I almost completely forgot they existed, but years later, attending middle school in Brazil, I learned that basically every young girl on the planet was madly in love with this funny, fart-noise-making actor. My brother and I got some of those pictures printed, and soon every girl at school was begging us for a signed copy of it. My brother and I started selling the pictures for about two bucks, learning about entrepreneurship in the process. Now that was fun. Today, as I see DiCaprio flying around the world on private jets lecturing me about my “carbon footprint,” it makes me want to barf. Still, as a kid, it was cool to claim I knew him. Those two memories were important learning experiences. People can be cruel if you can’t blow out candles, but they can be cool if you knew a handsome celebrity, making you Mr. Popular. Are people that pathetic and superficial? Certainly, many of them are. It’s sad but true.

Though I didn’t really think about it until years later, the relatively small white minority in Mexico really did hold almost all the power, both economically and politically.

My Time in Mexico Taught Me About White Privilege