Man and women working together|Woman and man at work|Men laughing together in office|Men playing ping pong at work

Man and women working together|Woman and man at work|Men laughing together in office|Men playing ping pong at work

My Uphill Battle Against Bro Culture as a Queer Woman in Tech

Being a gay woman in software sales is challenging, to say the least. I’ve been doing it for almost ten years—first in Silicon Valley and now in New York City’s Silicon Alley—at top-performing “software as a service” (SaaS) companies, and I still require constant pep talks that things will get better. After a decade of interactions in male-dominated tech culture, I’m starting to doubt they ever will.

I’ve Heard “Girls Can’t” My Whole Life

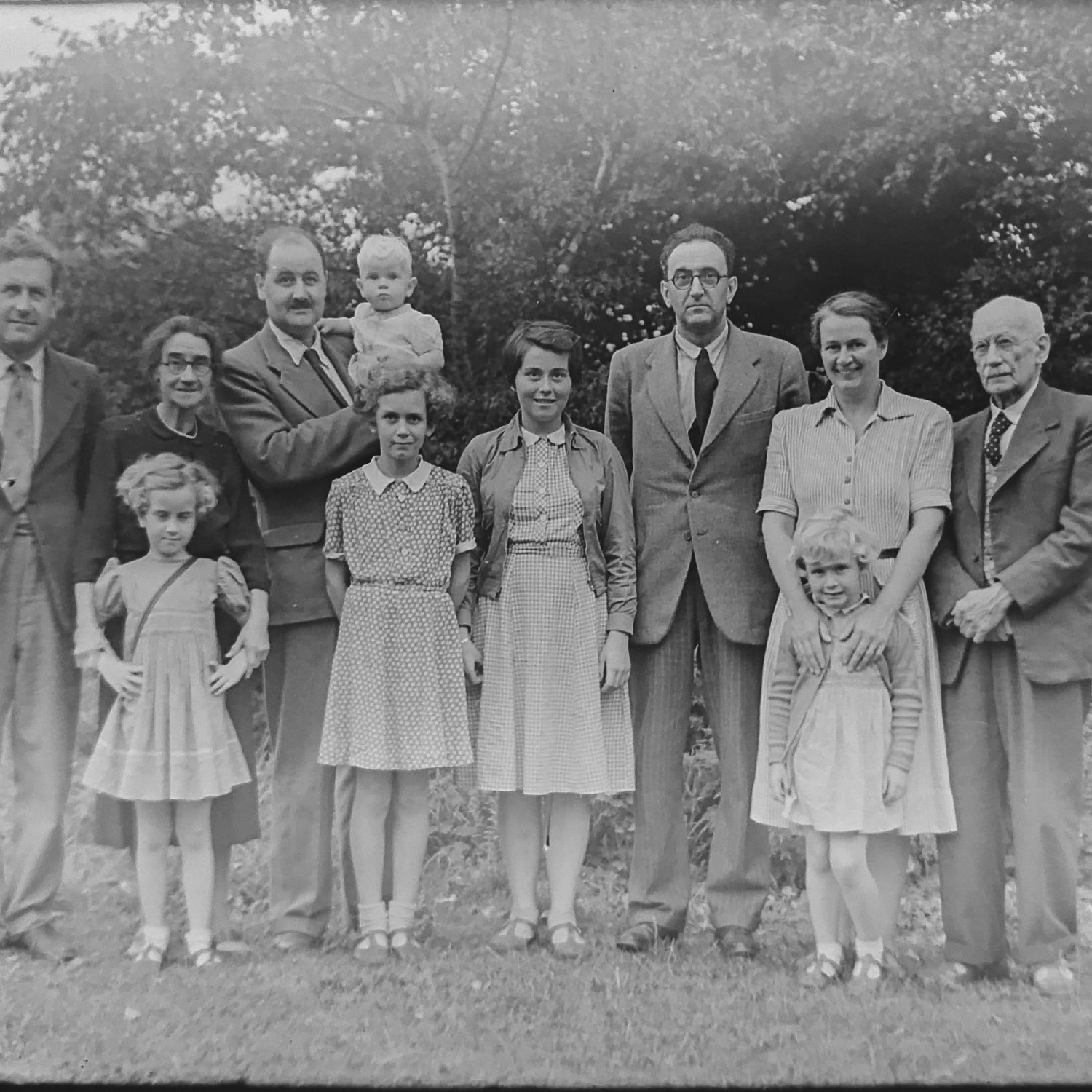

As a gay woman from the Midwest—with two older brothers, a breadwinning (now Trump-supporting) father, and stay-at-home mother—the image I grew up with of who or what a woman could be was very limited. My brothers were given opportunities that I had to work twice as hard for, ones as simple as the space to have an opinion at family dinner, or as trivial as being allowed to go with them to a DMX concert in Cleveland or play the same sports. I wanted so badly to join my brothers’ football team, and the answer I was given—that “girls can’t play football”—was the first of many times I would be told that girls “can’t do” something I knew innately that I could. Anytime this happened I walked away feeling frustrated and lost, a feeling that would stay with me for all of my childhood and adolescence (and most of my adult life). Any time I experience or witness a microaggression or small injustice in the workplace, I’m immediately struck with that same childhood feeling of frustration and vulnerability. I wish that this was about all of the tools and tactics I now use to combat sexism, how empowered I feel as a gay woman in tech, how it’s gotten so much better as I’ve grown older—but it's not. The white men leading my companies aren’t telling me I can’t go to the DMX concert or play football, but their words and actions are just as harmful, and a constant reminder of all of the “can’ts” in my childhood that persist decades later even as a talented, successful, high-performing sales executive who just happens to be a woman.

Any time I experience or witness a microaggression or small injustice in the workplace, I’m immediately struck with that same childhood feeling of frustration and vulnerability.

Bro Culture in Tech is Real, and It’s Bad

From my experience, the tech world is aggressive as it gets when it comes to gender inequalities. The software company I started working for in San Francisco prided itself on the bro-ishness of its corporate culture. I often watched my male coworkers on client calls, in their wireless headsets, swing baseball bats while they built a rapport around sports. I remember the moment I decided I’d had enough bro culture. I confided in my boss, a white male in his early 60s, that it was time for me to move on to my next chapter and leave the company to start something new. “No,” he replied. “I need you to wait to tell me this in two weeks. Until then, this conversation never happened.” I was shocked.For the next two weeks, I drove myself crazy trying to understand. Why wouldn’t he let me quit? Two weeks later I found out when he pulled me into a room and told me he was being laid off for poor performance. He wanted me to put in my two weeks that day and tell his leadership it was because they were getting rid of him. At the moment I couldn’t even comprehend all the feelings I was experiencing. I had worked at this company for over four years and grew the team from 100 employees to over 400. I’d opened the company’s new office in New York City, and I was one of its top performers. Now, he wanted me to define my moment of departure as being all about him and protecting his image and ego. I resigned that day and told his leadership that it wasn’t because of his departure, but I couldn’t escape the optics. At this moment I was met with the same childhood feeling of vulnerability and frustration. A career-defining juncture had been taken away from me, and my accomplishments at this company had been given to someone else.

I Thought Things Would Be Better Outside Silicon Valley. They Weren’t.

I’ve since moved on to a startup to take a chance in shaping the inclusive culture I’ve always desired as a queer woman in SaaS. I was the first employee hired to join the white male co-founders and was promised the opportunity to influence hiring decisions and company culture. For the first time in four years, I was hopeful that real change might be possible, and that bro culture and tech culture weren’t permanently intertwined. My hopes were short-lived. As the company grew, so did the layers of straight white male leaders that were established between me and the founders, and I watched the culture slip back into a familiar pattern. The company claimed to focus on diversity and inclusion, but it quickly became clear that there was a lot of hiring bias. When my team opened up a vice president of sales position, we interviewed female candidates at the top of their field who were met with internal feedback like, “She’s great, but will she be able to command a room?” All I heard is, “She’s great, but will people respect her as a woman? Because I don’t.”

My hopes were short-lived.

Equality for Women Leaders in Tech Exists Only in My Dreams

Most recently, the company made the comfortable decision of bringing on a middle-aged white man to lead the sales force, despite the team already being 75 percent white men. Within two months of my new boss joining, he wasn’t afraid to tell us that, “This is my team and you’re going to do what I want.” The tipping point came in June 2019. I hid who I am for the majority of my life before I finally came out in my mid-20s. For this reason, Pride month has come to mean a lot to me, and my sense of place in the community. With my company's claim to focus on diversity and inclusion, I sat down with my CEO in to eagerly discuss my ideas for how we can support the LGBTQIA community and honor Pride month as a brand—after all, their top-performing employee (me) was a part of this community. To my surprise, I was met with immediate resistance, as my CEO didn’t want to take a “political stance” because he was concerned that it could prevent prospective clients from working with our company. I knew he loved Chick-Fil-A, but I wasn’t expecting this. It hurt me down to my core. Here I was on the frontline of his brand, building relationships, hosting dinners and meeting with prospects every day, yet he was concerned about people knowing that the company supports the LGBTQIA community? I felt frustrated and vulnerable again, like bro culture and talking about sports are acceptable in tech, but to be your authentic self as a gay woman is not. My identity is somehow political.After years of red-eye flights, nights away from my wife and working on weekends, here I am again, realizing that there’s no amount of persistence or contribution I can make that will cancel out the sexist culture that is so deeply ingrained in SaaS, Silicon Valley and tech. The culture I had so badly wanted to distance myself from was seamlessly coming together right in front of my eyes with each new (white, male) employee we hired. Here I am again, watching a male counterpart in a meeting repeat a point I just made, and the (predominantly white, male) room reacting as if they’re hearing it for the first time. Or having my boss interrupt me while I’m making a succinct argument or explaining something important. Despite my years of experience and expertise, here I am again experiencing first hand the things that women “can’t” do—like command a room. Unfortunately here I am again, feeling stuck under these white men who need power, and somehow I’m the person who’s made to feel like I should leave. I used to dream of one day joining a company early enough to have a hand in building it up into somewhere a queer woman—or really anyone who wasn’t a straight white man—could feel like a valued part of the team. All these years later, I’m still dreaming.