Man with hand up|Football player|Man looking

Man with hand up|Football player|Man looking

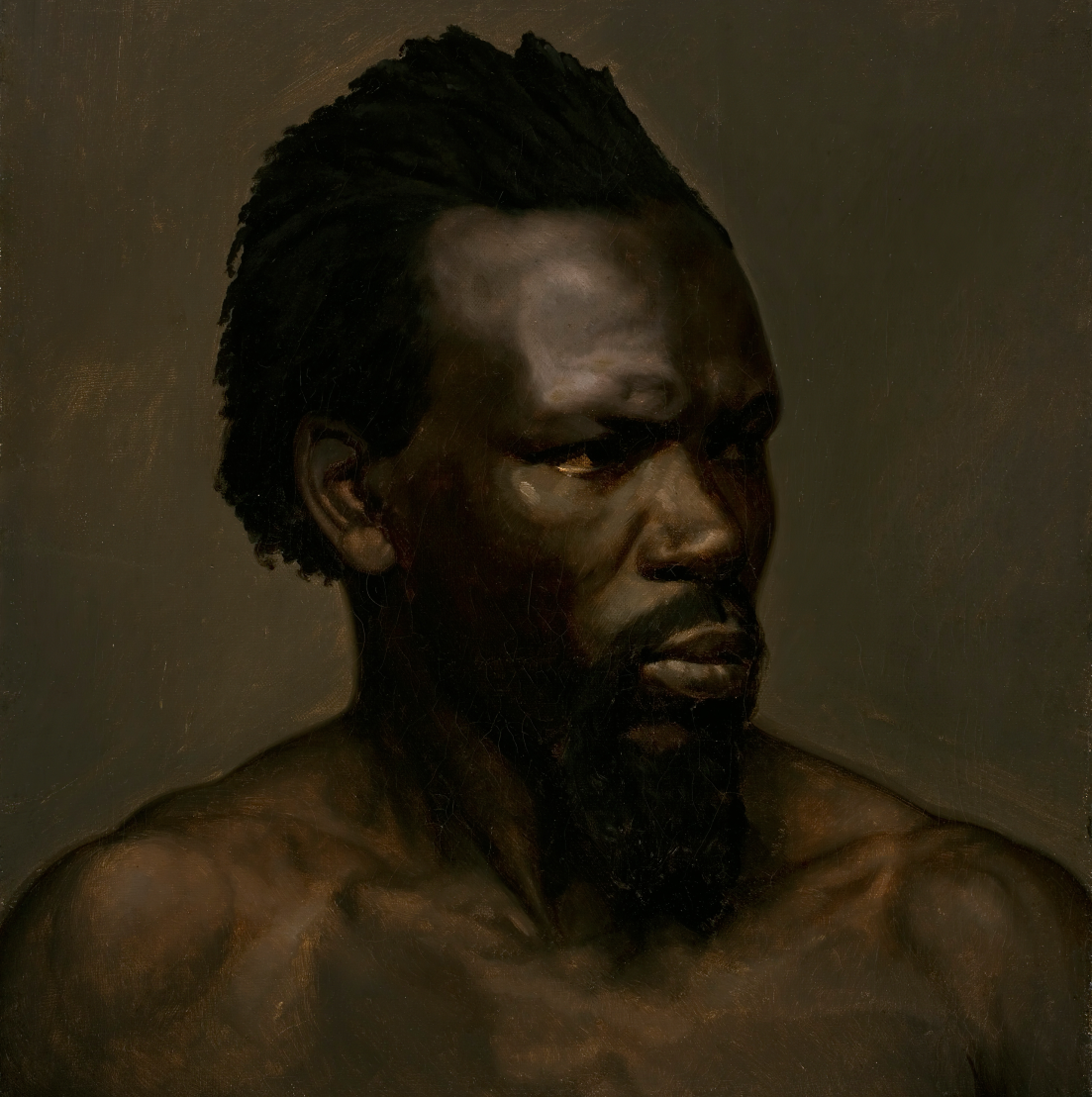

Rural America Sees Black Men As Athletes, and Not Much More

I identify as a Black, queer, intellectually disabled man who is living in modern-day America during a pivotal moment in history. I write this during a time when the world is experiencing racial injustices and the horrific pandemic of COVID-19. Many of my Black brothers and sisters have experienced gun violence by white Americans, only to end up in a tragic death.From my birth, I navigated the world with a different lens than the other Black men around me. I grew up in South Georgia, a place where men were usually socialized through sports. Although academics are often praised—and enforced—in the households of my hometown, Tifton, Black men here are often perceived only as athletes. Sports have been a constant stressor in my life. My brother became a professional athlete when I was in middle school. My maternal uncle was the first athlete to ever receive a scholarship at his university for two sports: football and baseball. I never engaged enough in any games or developed any athletic skills.

Athletics Can Liberate Some Black Men—but Not All

I had a close-up view of the countless hours my brother dedicated to baseball and many of the issues with racism that he experienced from the start. At that time, all of the coaches for male sports in the public school system (except basketball) were white men. I noticed that these white men only cared for the Black athletes until their senior year, if they made it that far.Access and equity for Black students within public school systems in rural areas like Tifton face significant challenges. The Black athletes who were advanced enough might receive some support, but many wouldn’t even get the help they needed to graduate high school. Of the Black men in my graduating class of more than 500 students, fewer than ten of them have gone on to earn a bachelor’s degree. Black male athletes’ bodies in Tifton are used to generate sports funding, yet a disproportioned number of us do not have academic success in the classroom. Considering the four million dollars my hometown spent on renovations for their football stadium in 2008, the low number of Black men who matriculate into higher education to earn a bachelor’s degree is alarming.

Why It Took 16 Years to Discover My Learning Disability

My educational journey required me to manage my own academic challenges along the way. My academic performance was inconsistent from elementary school until my senior year of college at Georgia Southern University. I would flourish in English and history but struggled with math. I had to retake college algebra the same semester I scored 102 in one of my history courses.After a meeting with my college algebra teacher, where I could verbally walk him through how to answer several problems on a test but couldn’t correctly write them out, he recommended that I visit the school’s disability resource center. They did an evaluation and referred me to a local psychologist for a psycho-educational assessment. After a month-and-a-half process, 14 hours of testing, and a two-week wait for the results, I received notification that I had been diagnosed with a cognitive processing disorder—after 16 years of school where I didn’t even know I had a learning disability.I believe that part of the reason I discovered my learning disability so late is Tifton’s rural location. Rural areas in America are often under-resourced, so school systems don’t always get the funding they need. Even now, Georgia governor Brian Kemp has decided to make cuts to education during the COVID-19 pandemic—a pandemic that happens to be occurring in conjunction with the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and the long, sad list of other unarmed Black Americans who’ve been killed by white men.These tragic deaths occur on concrete sidewalks, in the isolation of our own homes and even when we’re peacefully walking home from purchasing Skittles from a 7-Eleven. I agree with Bishop T.D. Jakes that, “Blacks deserve justice in the courtroom, not on the concrete.” My soul is fatigued from advocating so long for my Black people. I marched for Trayvon Martin and for Troy Davis. These injustices happen all over our nation and world, but have increasingly occurred throughout the State of Georgia. Ahmaud Arbery’s murder hit home for me since it happened only 100 miles from Tifton. Kendrick Johnson was killed less than 40 miles away.

Education and Community Can’t Be Separated

There are a lot rural communities in Georgia and across our country. Beauty exists in these places, but so does overt racism, due to lack of access to knowledge. Some of them are home to reputable public schools, colleges and universities. I think it is important to examine the bridge between those institutions and the places they’re located, and what these institutions are doing to dismantle racial injustices, starting with having conversations about racism in the community.Through it all, I remain hopeful that Black folk will persist through these racial injustices by clinging to our spirituality and being in community with each other as we have during difficult times throughout history. Food is how many of us connect. My grandmother Doretha cooked each Sunday for 23 years. I still vividly remember walking into her house after church to smell fried chicken, cornbread and delicious Southern food.Being in community with each other is a healthy outlet for Blacks during these harsh times.Yes, I navigate this world as a Black, queer, intellectually disabled man. Although my Black brothers and sisters vary in their social identities, I see me when I look at them. I think about the biblical story of Moses, who delivered his people out of Egypt and into the Promised Land. Moses was an Israelite who delivered freedom to his own people. Today's liberation of Blacks will come from us liberating our own people, ourselves—no one else.