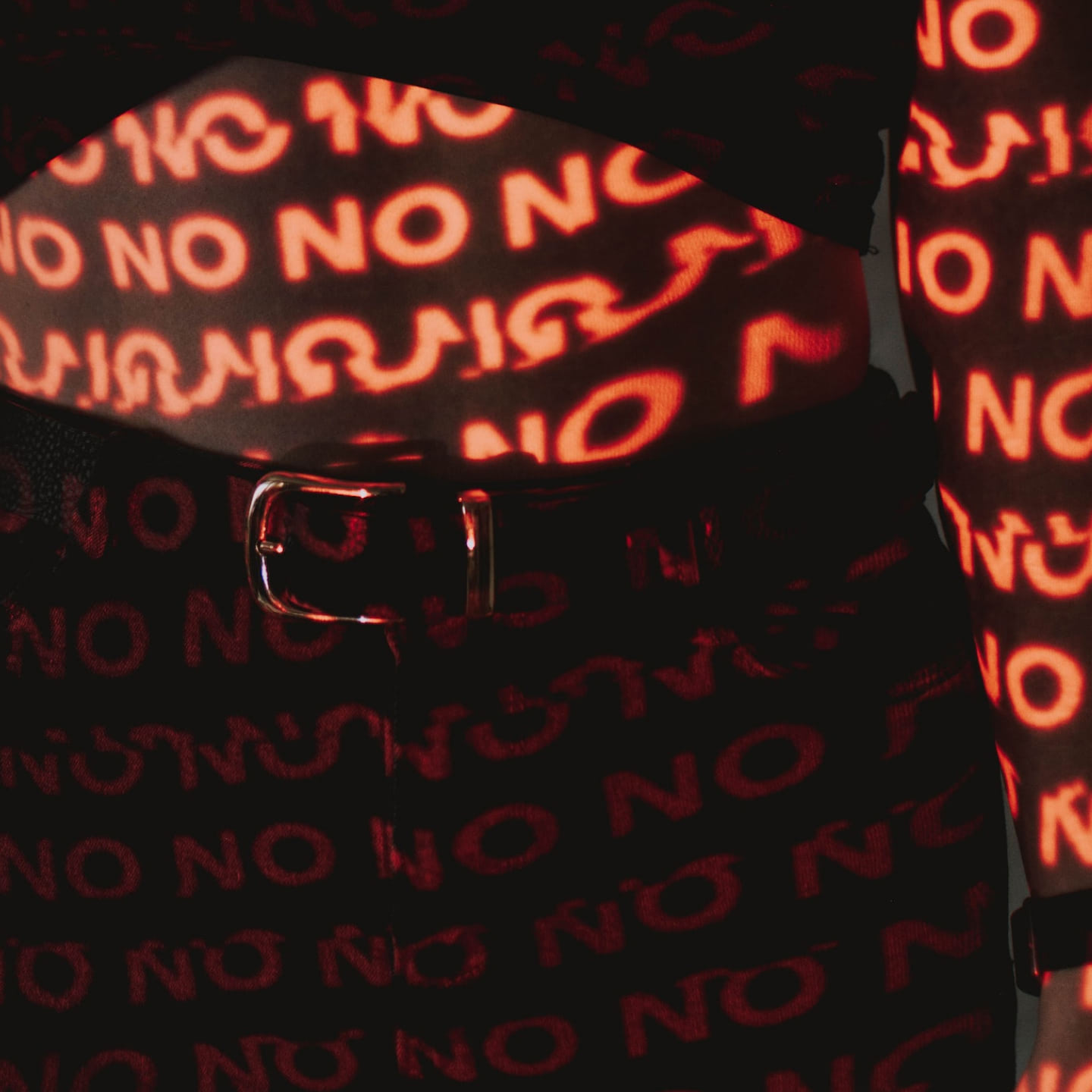

I Quit Nursing Because of the Pandemic: I Am Never Going Back|A new nurse struggles with lack of support and training during the pandemic.|A nurse protests for higher wages and better working conditions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I Quit Nursing Because of the Pandemic: I Am Never Going Back|A new nurse struggles with lack of support and training during the pandemic.|A nurse protests for higher wages and better working conditions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I Quit Nursing Because of the Pandemic: I Am Never Going Back

“Why did you want to be a nurse?”I’ve been asked this question a hundred times, but I’ve never given a concrete answer. There were many reasons. As a small child, I poked and prodded my parents with the tools from my toy doctor’s kit. The day my brother came home from the hospital, I introduced myself to my mom as “the baby’s new pediatrician.” In high school, I was curious about both the caring and academic sides of medicine, but it was far from my only interest. I’ve thought about pursuing careers in psychology and international relations. I’ve loved singing, acting and art. I ended up with bachelor’s degrees in English and religious studies. Many nurses say their profession is their “calling,” but I can’t shake the feeling that I became a nurse by accident.After graduating from college, I started a career in early childhood education. I love children but didn’t love the pay and the reputation that came with what many people consider “glorified babysitting.” I knew from family members’ experiences that nursing paid well and that it was possible, even common, to go to nursing school after several years of working in an unrelated field. So, one weird March day in 2018, while contemplating my life’s purpose in a Dunkin’ Donuts, I decided to apply to nursing school.

My Schooling Was Cut Short Because of the Pandemic

In May 2019, I was accepted into an accelerated, 11-month Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at an in-state university. I knew learning a new trade in less than a year would be challenging, but this program had a stellar NCLEX pass rate, and I’ve always been a good student.I loved nursing school. I had wonderful professors and excellent clinical rotations. I made friends with a few classmates, some with even odder backgrounds and paths to nursing school than mine. I made A’s in all my classes, and I could picture a clear career trajectory following graduation.Then, the pandemic hit. What we thought would be two weeks of online classes turned into two months and then the rest of our program. Challenging in-person labs and clinicals were replaced with lame virtual simulations. We earned optional four-week hospital internships in July. With no curriculum to guide me, I spent most of my internship confused. Our program should have been extended a semester. Instead, we were allowed to graduate and sit for the NCLEX on time, barely scraping the state’s requirement for in-person clinical hours. I received under seven months of hands-on training before earning a license that allowed me to practice nursing. If this fact doesn’t terrify you, it should, because I wasn’t the only one.

If this fact doesn’t terrify you, it should, because I wasn’t the only one.

Nurses Eat Their Young—It’s True

My university had a solid relationship with the area’s major hospital system, so I had no trouble finding a job. I really wanted to work on the pediatrics unit, the only unit that was (at the time) downsizing due to the pandemic. I ended up in an adult neurology intermediate care unit. Patients in intermediate care units are considered “critical but stable.” Most of the patients in my unit had suffered massive strokes. Many had both neurological damage and COVID-19.New graduate nurses work alongside preceptors for a few months before they’re allowed to work independently. My first preceptor fit the “eats her young” bully stereotype that all new nurses fear. She offered me little encouragement and hands-on instruction. She expected me to remember every line of my nursing textbooks. She humiliated me in front of a patient’s family. I knew I was doing poorly, and she didn’t let me forget it.After two weeks, this preceptor went part-time, and I was assigned someone else. My next preceptor was more understanding and a much better teacher. Under her five-week instruction, I gained a lot of confidence. On our last day together, she told me that I was doing “fucking amazing.” But after she transferred to another unit, there was no one available to be my permanent preceptor. Once again, I struggled. I was led to believe that my lack of consistent training was not the reason why I was failing. My manager blamed my shortcomings on my personality, never mind that she hired someone with no previous hospital employment and a pandemic education on a difficult unit that lacked reliable preceptors. When I expressed that her constant questioning of my potential was not helpful for my professional development nor my mental health, she declared that she would “not take responsibility!”She was, however, totally right that I was not ready to be a nurse on a large critical care unit. Ultimately, I was thankful to her for saving me from further failure and humiliation.I worked for another three months in an outpatient setting. It was a decent job, but I felt unfulfilled working below my education level. I was also paranoid about screwing up again. This time, I received a lot of support and reassurance, but was still let go “at will.” Basically, “We didn’t hate you enough to fire you before the end of your probationary period, but we don’t like you enough to keep you on. We didn’t owe you any warning or any explanation.”I told my boss at my second job that I was quitting nursing. She moaned about how I had so much potential, and I shouldn’t give up. “You’ll forget about this experience in a few years,” she said.I will never forget. And I have quit.

The Pandemic Made an Already Miserable Job Worse

Well-meaning doctors and medical journalists like to claim that if we want COVID-19 nurses to stick around, we should “try paying them more.” During my time at the hospital, all nurses and nursing assistants received five-dollar raises. The nurses who worked through the early months of the pandemic were also given higher-than-usual holiday bonuses. Better pay was not enough to increase morale because nurses are not just underpaid, they’re also undertrained and overworked.I was responsible for feeding, bathing, assessing and administering medications to three critically ill patients at a time. I had to do so safely, swiftly and happily while sporting layers of PPE. I was also expected to complete several hours’ worth of charting each shift. If I didn’t take my 30-minute lunch break, I’d get called out for coming off slow and shaky. If I did take a break, I’d fall behind. My co-workers were better than me at hiding their stress from patients and from our manager, but I watched them cry in hallways, bathrooms and break rooms every day. Over half of these nurses had one year or less of registered nursing experience. Most of the rest were travel nurses, who have the luxury to ignore office politics and take several weeks off between jobs, as long as traveling fit their lifestyle. When I tell people that I quit nursing because of COVID-19, I don’t mean that watching people die from the virus was too much for me to bear. I knew that getting up close and personal with death and suffering would be part of the job. I also knew that working 12-hour shifts, nights, weekends and holidays would be part of the job. I knew that I would feel exhausted and terrified the first few months. I never imagined that my supervisors wouldn’t give a shit about how I felt.Nurses “eat their young” because they know that it’s easier to scare straight or scare away the newbies than it is to fight against the status quo. Before the pandemic, around one-third of nurses left the profession after two years. Now throw in fear of contracting COVID-19, constant understaffing, increasingly unsafe nurse to patient ratios and frustration with anti-vax patients. In September 2021, The Washington Post reported that all healthcare workers were leaving their jobs in record numbers. We should be more worried than ever about the state of the nursing profession.

I never imagined that my supervisors wouldn’t give a shit about how I felt.

Quitting Nursing Helped Me Find My True Self

In a world without a pandemic, I may have had better career counseling and landed a hospital job that better fit my qualifications and interests. Even in the real world, I could have found another nursing position following my two failures. A desperate doctor’s office or nursing home would have taken me on—anxiety, incompetency and all. Eventually, I could have learned to be an excellent nurse. An excellent and very unhappy nurse.This horrible experience helped me realize what I value most: my friends and family, my creative expression, my independence, my mental health. I still strive to help others through my writing, through volunteering and through everyday acts of kindness. Nursing will always be an important part of my past, but it’s not part of my future.