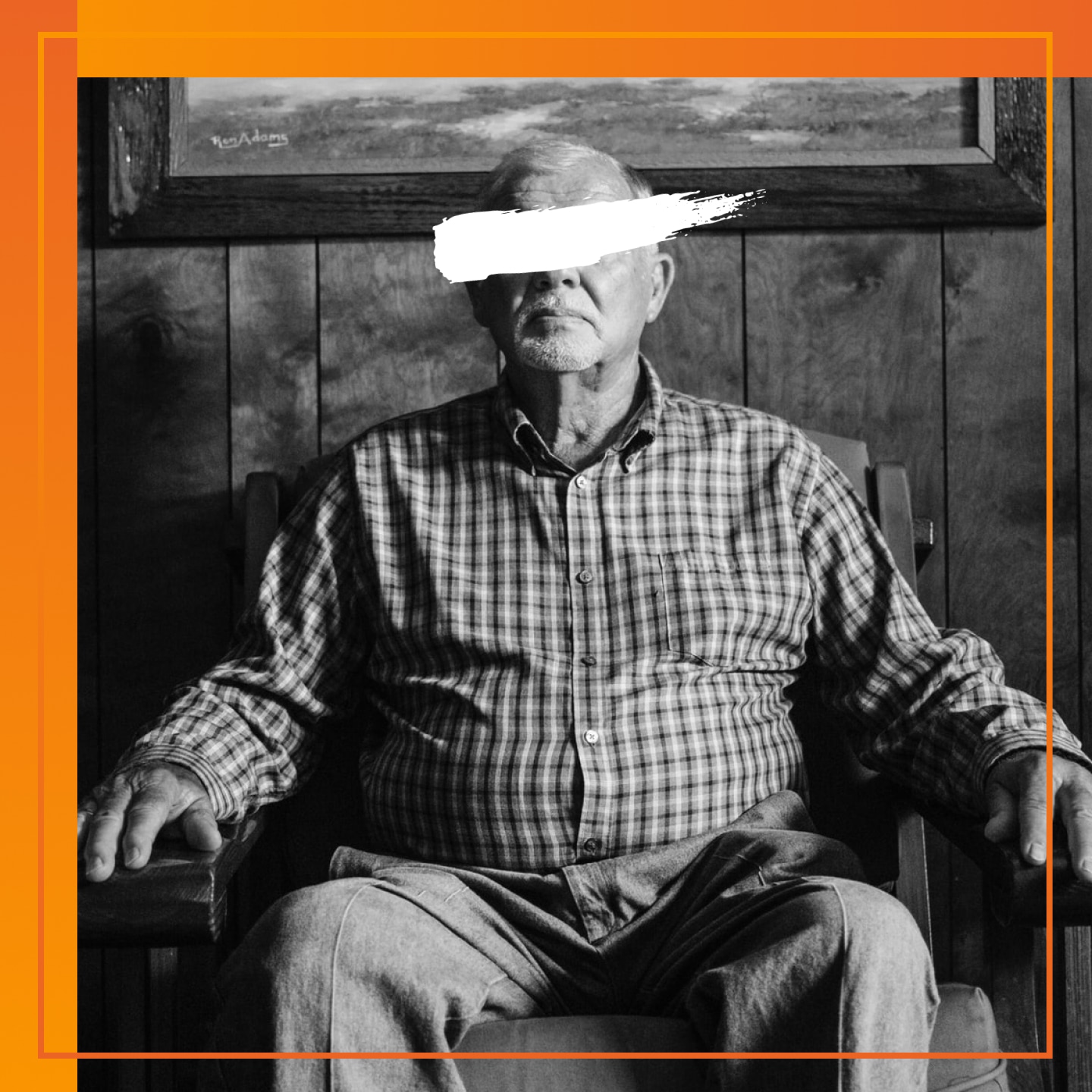

My Father, the Tyrant|A man turns to drugs to fill the void of his emotionally abusive father.|A young boy longs for the love of his distant father.

My Father, the Tyrant|A man turns to drugs to fill the void of his emotionally abusive father.|A young boy longs for the love of his distant father.

My Father, the Tyrant

I’d never heard of Father’s Day. Not until I was asked in junior school what I did for my dad on his special day. For fuck’s sake, I didn’t even know when his birthday was. My father loathed such “petty” celebrations. Christmas and birthdays were miserable affairs. My mom would secretly give me a card and a little money and books—always books. For that, I am truly grateful. I couldn’t get enough of encyclopedias, along with the delightful, if dated, works of Enid Blyton, who created worlds I could lose myself in. Around 1970, just before we left London for the miserable but spectacular vistas of North Wales (think Seattle with hills surrounded by beaches), my form teacher asked what I wanted to make or paint for a Father’s Day present. Teachers should think this shit through. Life is not all fluffy bunnies and rainbow-covered fields. Some kids live in frightening conditions and, in my estimation, the most frightening experience for a child still trying to find their way in the world is living with an aggressive, cold and indifferent father. My mom fought my dad for 22 years before garnering the courage and opportunity to finally divorce him. In all those years of marriage, my father had not once taken her out for a meal or a dance or a movie. He turned birthdays into anxious and depressing occasions; the same went for Christmas. In the midst of all this Father’s Day business was something I learned in school—how “normal” families celebrated their love and affection for the archetypal father.

The thing I missed was the pat on my back from my father, one that I realized later in life would never come.

My Father’s Lack of Support Drove Me into Dark Thoughts

Two years later, I attended an incredible school set in a beautiful valley called Croesor, full of myths, legends and fairy tales. At break times, we could fish for trout sitting on the school wall, casting our hopeful lines into the crystal clear water of the river that gave the valley its name. The school had 22 pupils, and for all my inner turmoil and aggressive outbursts, we all thrived because there were three teachers, a dinner lady who played piano and taught us music, and an eminent biologist who came in once a week and taught us everything she could about the life that ebbed and flowed—the microscopic cyclops, the formidable-looking larvae of dragonflies, leeches and eels. Yet, for all this input from fabulous teachers, the thing I missed was the pat on my back from my father, one that I realized later in life would never come.As a result, my behavior had deteriorated, though I still earned straight As. I received pats on the head and compliments about how amazingly clever I was; the future was mine for the taking. I’d smile, but inside I was already experiencing suicidal thoughts. They kicked in at around age 10 or 11. There were two main triggers. Firstly, I was terrified of moving into a bigger Welsh school that had a reputation for a lot of fighting. It reached the point where I was seen by a child psychologist who looked at my handwriting and asked me fairly tame questions about school and home. Of course, I lied and said my dad was superman and my mom an angel (she was that for sure). I was also afraid of my temper and what I might do if I lost it—so a couple of years later, I started smoking hash and weed. I drank a fair amount, too, and had my first experiences with psychedelics. Not ideal for a still-developing child’s mind which had already been subjected to serious trauma via an accident that cost me half a lung. I was enjoying the punk rock scene and various substances. It was much later in life I came to understand I was masking my true self through reckless, dangerous and suicidal intensity in almost everything I did.

My Father Regularly Crushed My Spirit, Triggering My Contempt for the World

On Father’s Day of 1972, Mrs. Jones, the headmistress, got me to make a piece of pottery for my dad. It was a colorful ashtray (he smoked quite heavily)—painted blue, green and red with the words “Happy Father’s Day” in English and Welsh—and I was pleased with my efforts. I took it home, nervous of his response. He did actually have his jovial moments but they were few and far between. I remember walking into the kitchen where he would sit with his books and a pile of paperwork surrounded by a haze of Old Holborn tobacco smoke. To this day, if I catch a whiff of that tobacco, I’m back in that cold, frightening kitchen. “Go on, say, ‘Happy Father’s Day’ and tell him you love him,” my mom and grandma said. I rehearsed the lines in my head—I was shitting myself. His disappointment in me was always on show; I held out the ashtray. He examined it, ran his fingers over the glaze and said, “Yes, they’ve been telling me you’re clever, so forget about that love stuff and think about what damaged goods like you might be able to do in life.” I said I wanted to join the army. He said they’d never take me because of my eyesight and the accident that cost me half a lung. By the age of 29, I was fighting the biggest and toughest guys, not in the army but in a prison. In that moment, and many others I could recount, he crushed my spirit, and from then on I was at war with the world, a war that led to amazing experiences as a musician—touring, making records, living my “Fuck you, Dad” dream. Then heroin hit London like a tidal wave in 1983, and I was someone who couldn’t stop using. Was my dad right? Was I destined to become a failure, a nobody low-life criminal?

Was my dad right? Was I destined to become a failure, a nobody low-life criminal?

I’m Hoping to Reset the Way I Think About My Father

It’s a painful exercise to revisit my memories of Father’s Day celebrations and an article like this can do no more than recount the bare fragments of memory. Years later, as I sit to rework the bones of this article I am struck by the potential for me to manipulate memory to feel a little better about myself and my tendency not to celebrate special days. But I also feel a deep and genuine sadness for myself as a child. At the beginning of my personal journey of recovery, I had a brilliant counselor who did a little exercise with me, asking if I could revisit the day I gave my father the ashtray I’d crafted to rework my father’s response in a visualization. In this version, he smiled and simply said, “Wow, that’s fantastic. Thank you, son. And what’s more, I love you very much.” It’s pretty much the way I relate to my own adult daughter.In playing out a healthy interaction, I reset my relationship with myself and let go of my now long-dead dad. A cautionary tale or simple therapeutic anecdote? I guess that’s for the reader to decide. I would like to close with a request: Remember that special days like Father’s Day can matter far more than we know, so celebrate. Let your pa know that you love him and be ready to accept whatever clumsy response he may have. Happy Father’s Day to dads everywhere.