How Twins With Different Skin Colors Perceive Racial Identity|How different family members perceive racial identity|the importance of racial and ethnic identity|Raising children to be the change in the world

How Twins With Different Skin Colors Perceive Racial Identity|How different family members perceive racial identity|the importance of racial and ethnic identity|Raising children to be the change in the world

How Twins With Different Skin Colors Perceive Racial Identity

“Dad, which box do I tick?” my brother asked when he reached the ethnic monitoring section of his first job application.“Which category best describes your ethnicity?” It’s an easy question for many people, but one that’s never sat comfortably with me, because I tick a different box from my twin brother. My brother and I were born in 1984 in Northern England and grew up knowing little of the Caribbean and Indian ancestry on our father’s side. I have blonde hair, green eyes and white skin. My brother has black hair, brown eyes and brown skin. It’s not something I ever remember noticing when we were young. My parents don’t recall any instances where we were treated differently. My mum said that if anyone commented on our appearance, it would only be to notice how much I looked like her and how much my brother looked like my dad.As we got older, we began to notice the evident surprise when people found out we were twins. It became a conversation starter, an interesting introduction when we met someone new. It was fun seeing peoples’ reactions. “Twins?! But you look nothing alike!”

I have blonde hair, green eyes and white skin. My brother has black hair, brown eyes and brown skin.

Growing Up, Being Mixed Twins Didn’t Seem Like a Big Deal

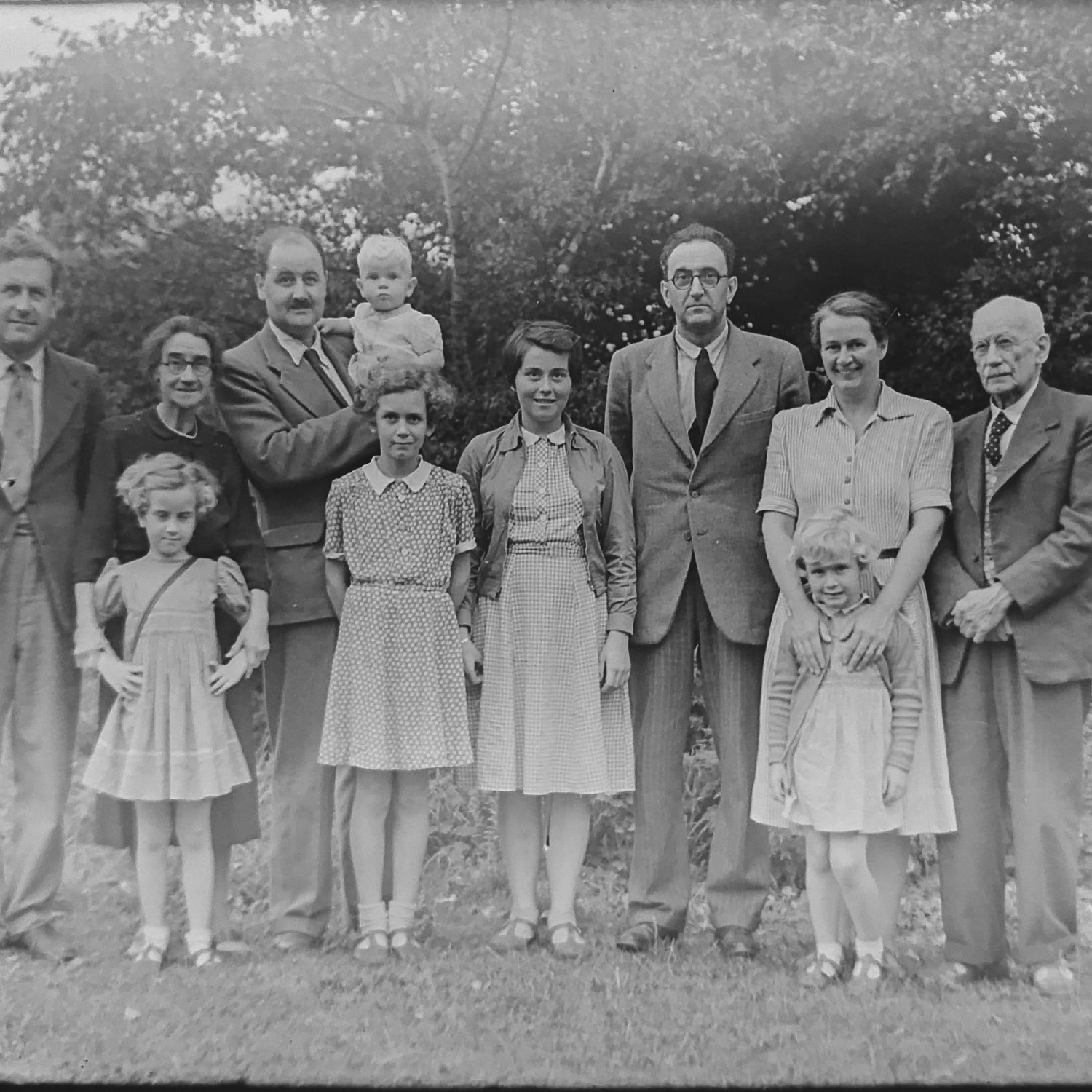

There were a few occasions over the years when, to our horror, we were mistaken for boyfriend and girlfriend. The only time things ever got truly uncomfortable was on a family holiday to Egypt in our late teens. My brother was so immediately perceived to be Egyptian that children spoke Arabic to him. Some teenage boys joked that we couldn’t be twins, and that my mother must have had an affair with a dark-skinned man. (My brother has darker skin than our dad, and when Dad’s hair turned grey, the boys were oblivious to their similarities.)We laughed off the comments, but it was an uncomfortable experience, particularly for my brother. It’s the only time he’s ever been singled out as different from his family. To me, that he should so readily have been identified as Egyptian demonstrates the problems of dividing people into categories based on perceived racial traits. While we never experienced racism growing up, we did at times encounter curiosity about our heritage. We were curious too. It wasn’t something our dad openly talked about when we were children. His parents divorced when he was three, and he never saw his father again. We knew our grandfather emigrated from Trinidad to serve in the Second World War. Our mum showed us photos of him in his Royal Air Force uniform, and of him and our grandma on their wedding day. Dad once met his grandmother, whose own mother was Indian and had traveled as a baby by boat from India to Trinidad with her parents, who tragically did not survive the journey, to work in indentured servitude. Our great-grandmother married a Trinidadian man, whose own father emigrated from Barbuda to Trinidad following the abolition of slavery, and they had several children, including our grandfather.

Our Dad’s Racial Identity Made More Sense Once We Met Our Grandfather

Our dad made contact with his father ten years ago after a friend researched our family tree and found him. He’d remarried and had more children. The reunion was no big drama, no tears or recriminations. His response to not seeing Dad for over 50 years was a shrug of the shoulders and a comment, “Well, I left you my telephone number.” The past didn’t really seem to matter. We were just one family meeting another family, curious to get to know each other.We got together with my grandfather a few more times over the years until he died. It was interesting to see the traits he shared with my dad. Both are charismatic, motivated and sometimes stubborn men. (Though, unfortunately, Dad hadn’t retained all his own teeth, which at age 90 my grandfather was very proud of.) My grandfather also identified very much as British and was adamant he’d never experienced any racism, a narrative that seems to echo my dad’s experience. Growing up in 1950s and ‘60s working-class Northern England, my dad has no recollection of ever feeling “other.” Much loved by the family around him, his mixed-race heritage was never a marker of identity for him. In his day there were no ethnic monitoring boxes to tick—he was just British.Both my dad and grandfather’s experiences may seem unbelievable from the outside looking in. There could be cases made for how their perception ignores the microaggressions perpetrated against them or the racism inherent in the systems in which they were raised. It could be argued my dad benefitted from the white privilege of his white family (though I don’t think anyone raised in 1950s working-class Northern England would describe themselves as privileged). Or you could say that my brother, our dad and his father before him succeeded in life despite their skin color. But they don’t feel that skin color has played a prominent role in their lives, and I don’t think their personal truths can be disregarded, or replaced by macro-level narratives that leave no room for their lived experiences.

I Hadn’t Really Thought About the Importance of Racial Identity Until Recently

So there are the “categories” of our ancestry: English and Scottish on our mum’s side and Caribbean, Indian and English on our dad’s side, yet a decidedly British identity for me and my brother. Our multihued family continues down the generations. My brother’s wife has fair skin and blonde hair and their son resembles her, whilst their daughter takes after my brother, with brown skin and black hair, though both children share the same beautiful brown eyes.Our identity has always felt tied to our family culture, rather than our ancestry. We didn’t pay much attention to our differences in skin color until the recent Black Lives Matter protests prompted discussions between us. Most importantly for me, I wanted to know if my twin felt he’d been treated differently to me on the basis of his skin color. He doesn’t. This is not to deny the existence of racism. I feel lucky that our family exists in a time and place where skin color hasn’t been at the forefront of our lives. I know this isn’t the case for everyone, and I welcome the recent resurgence of a commitment to eradicating racism in Western society.

Our ancestry has taught me never to judge a book by its cover.

Twins Born With Different Skin Colors Contradict Skin Color as a Determinant of Race

Where the current antiracist rhetoric fails me is in its divisiveness in its insistence that we set ourselves apart from each other on the basis of the color of our skin. For a family like mine, such reductionist narratives don’t fit. My twin and I are of the same “race”—all that differs is the appearance of our skin color. Yet current rhetoric would have us set ourselves apart from each other on this basis. I find it hard to understand why, in a progressive society where so many people clearly have a strong desire to eliminate racism, we continue to focus on the differences between us. People are complex, the world is complex and I can’t see how dividing ourselves into ever more definitive tribes on the basis of restrictive narratives will help our society reach a place where discrimination doesn’t exist. If you were here with me now, I would ask you to please look at me, then look at my twin. You may notice the differences in our skin color, but spend enough time with us and you’ll also notice our similarities: how we yawn the same way, stretch the same way, sneeze with the same annoyingly loud abandon (we get that from our dad). Whatever ethnic category box we do or don’t tick, it doesn’t really matter to us. They’re just labels. What matters is that we are a close-knit, loving family, aware of our rich and varied heritage, but not defined by it. Our ancestors’ indentured labor and slavery was barbaric, but it is also an immutable part of our history. Our family would not exist had the past not played out as it did.

Race Matters, but Skin Color Doesn’t Have to Be Part of the Conversation

Our ancestry has taught me never to judge a book by its cover. You can never really know someone unless you talk to them, but finding out about people is becoming increasingly precarious in a world where it’s so easy to offend.I will raise my children to be the change in the world that I want to see. I will teach them to recognize the privilege of their position in life, to equip them with a sense of justice and the courage to stand up to discrimination when they see it, but not to feel guilt for the whiteness of their skin—after all, their ancestors were slaves, too. To raise them to believe they are different from their uncle, their grandad or their cousin on the basis of skin color seems as ludicrous as ticking a different ethnic category box from my twin. It’s my goal to equip my children with an openness and curiosity about the world and everyone in it, to introduce them to a wide variety of cultures, people and experiences so that they don’t feel threatened by differences. I will encourage them to have compassion and empathy in their hearts, to have respect for their fellow humans and to listen to the stories of those they meet throughout their lives with curiosity and openness. It’s my hope that this will be a small step towards healing our increasingly fractured society.