How I Accidentally Became a Follower of a Hindu Guru |Hindu devotees conduct burial rituals at the banks for the Ganges river in Varanasi.|Mala beads for meditation made from rudraksha seeds.

How I Accidentally Became a Follower of a Hindu Guru |Hindu devotees conduct burial rituals at the banks for the Ganges river in Varanasi.|Mala beads for meditation made from rudraksha seeds.

How I Accidentally Became a Follower of a Hindu Guru

How long does a body take to burn? The body was set on fire. The wet cloth still clung to the skin and carved the silhouette of a woman. Soon, the cloth was engulfed, flames charcoaling the outer layers of her skin. Her right arm folded up to the sky as her muscles contracted from the heat. Her fingers began to liquefy at the knuckles. Her breasts were thin and melted. Fat burns first, then tissue, muscle and bone, I thought, uncomfortable with my lack of sympathy toward the event. Would I have felt differently had the body been in a church? The ghats in Varanasi are like outside auditoriums, with stairs leading down to the river where boats can dock. A few men lingered around a covered chai stall at the bottom of the stairs. Cows decorated with necklaces of flowers grazed the ashes while wild dogs drank from the flowing river. It was hard for me to tell who was a spectator, who was here for a burial and who was organizing the burns. There was no practice here I recognized from the Christian funerals I’d attended.“And there,” a man said. “See that man holding a club?”The man spoke to a few white foreigners as if a guide. I moved a little closer to the group. “See, he will be the one to release the soul. It’s often the eldest son.”He explained releasing the soul meant to crack open the skull once the body had burned. I didn’t linger to watch the eldest son smash open the human skull.

What the hell was happening?

I Met a Hindu Spiritual Leader Along the Ganges River

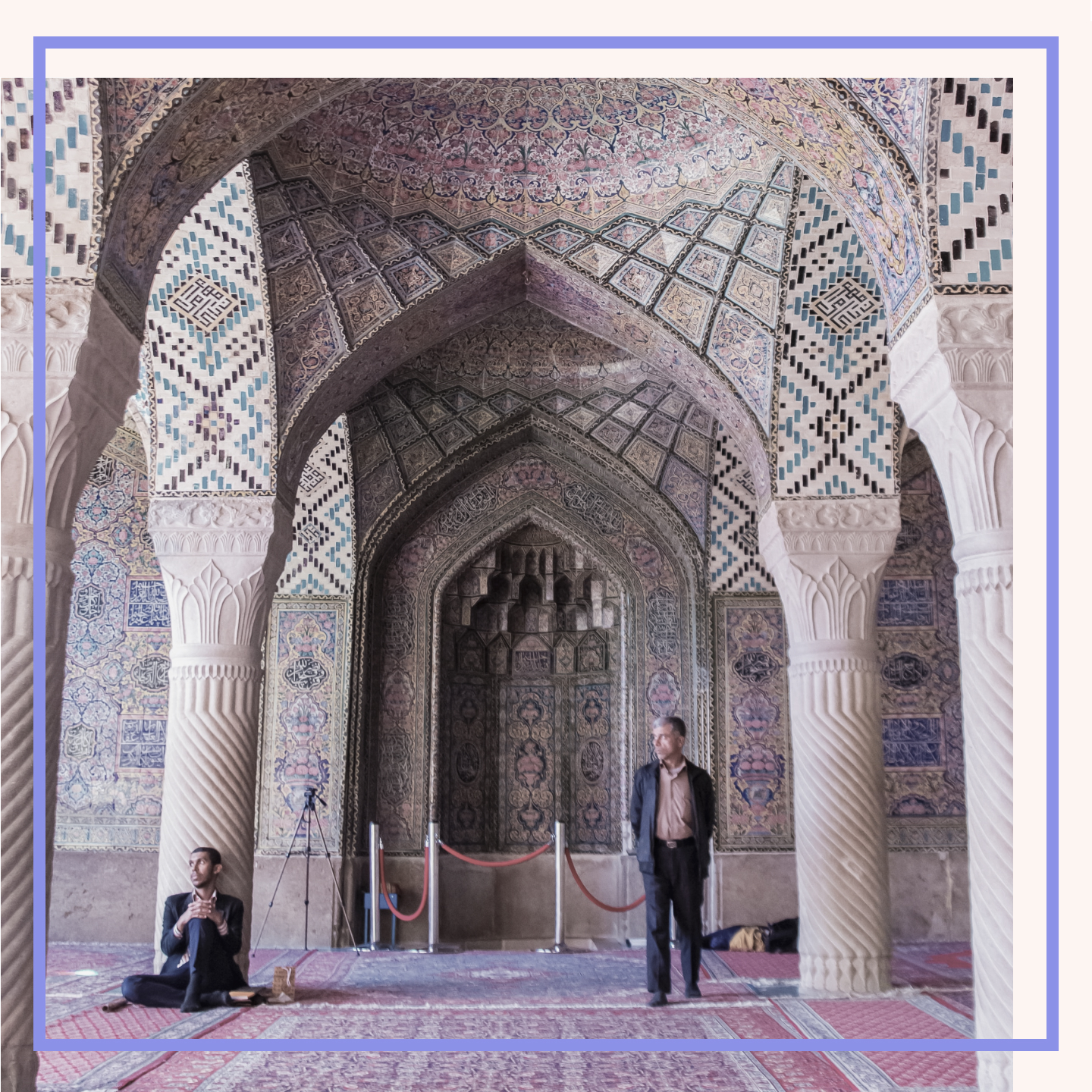

Visiting India was a bucket list destination: the vibrant colors, the spices, the food, the wildlife, the 1.3 billion individuals who had created a culture unlike anywhere else in the world. Then, there was the spirituality to the point of mysticism or magic that I’d read about in books. I wanted to feel the energy for myself, and, maybe naively, I thought it might settle a growing discomfort I’d acquired in the years of living in Southeast Asia, a discomfort in being a baptized Christain without practice or belief. Was there just one right way?I put the question of faith out of mind and focused on enjoying Holi, Hinduism’s spring festival. Varanasi was the place to be in India for Holi. I’d been walking along the Ganges in anticipation of being swept up in an exciting crowd of festivalgoers. Having slept in, the streets were quiet. I saw the circumstantial splattering but missed seeing the casting hands of the colored mess in the narrow alleyways. There was more life along the Ganges with a line of canopies set up. I was drawn to one tent where puppies were playing among the five men sitting on the carpeted ground. A man sat cross-legged on a large swing bed decorated with pillows and held by chains from the structure like a country porch swing. He called me to join his circle. He introduced himself as Nagababa, the swing baba. I knew of standing babas devoting their lives to never sitting or the baba who had held his arm above his head for 40 years until it was skeletal. Nagababa must have been confined to his swing. He was welcoming, asking me to sit and share from his pipe. He waved a large feather fan across his face and proceeded to ask me questions in English: Where was I from, how was my time so far, where was I going? His tone was curious, but his questions were rote. “I have disciples from all over the world,” he said. “People follow me. I am 20 years a baba. I am a swing baba my whole life, staying in my swing. This is a big time for the babas. From all over.”Nagababa asked the man nearest him to retrieve a phone from his bag and instructed the man to hand it over to me. “See the people who follow me.”I scrolled through the gallery in his iPhone sheepishly. I assumed a baba was similar to a guru or a monk or a priest tapped into a higher power, and it felt odd that he should have a phone-like technology dampening his spiritual credibility. “You can follow me too,” he said.His offer was straightforward, like a newsletter subscription, though I got the feeling following in the context of religion was meatier than the click of a button. “What does that mean to follow you?” I asked. “Do people give you money?”“It doesn’t matter. See the people, all the temples. I pray for you. It’s easy. You just message me on Facebook.”“So we just become Facebook friends?” I asked, a little disappointed having expected some grandiose ritual.“No problem. I’ll give you my mantra, and you take with you mala beads.”A mantra sounded familiar, but I had no clue what a mala bead was. Nagababa had one of the men prepare a pipe of hash. Nagababa hit the pipe first, coughing out smoke with the thickness of wool. He had his eyes closed and was speaking in a low volume from his swing. The group was silent while he spoke. I closed my eyes. I heard the chains of the swing clink and opened my eyes to see Nagababa standing from his seat rifling through his bag. I closed my eyes again, thinking I wasn’t supposed to catch him standing. Wasn’t the point that he never left his swing? “Here,” he said. I opened my eyes. He was back in the swing handing me a necklace. It was a cheap string that had a single maroon pendant that looked like a petrified cherry with holes drilled through the center. “This one is for you,” he said to me. “A special one. These are rudraksha seeds, from the tree.”“Thank you.”He continued to speak in a thick honey rhythm. “Now you have my mantra; every day, you can be with me. You are feeling good, yes? You are one of us. You are my follower now. This brings you luck.”I held the mala necklace, looking dumbly up at Nagababa, wondering if I had consented to something or had I accidentally undergone some ceremony to become a Hindu follower. I asked Nagababa to repeat his mantra into my phone so I could record in case I ever seriously considered Hinduism. I put on my necklace as Nagababa rose from his swing again to stand at the edge of his tent and wave goodbye.I tried to offer him money because the need to pay for getting high with a spiritual leader in India during Holi felt unavoidable. He didn’t accept the rupees nor did he seem offended by the offer, so I placed them on his swing, and he shrugged. I left, wondering about the boundaries of his devotion.

Nagababa Had a Unique Way of Showing Spiritual Devotion

In the evening, there was a ceremony to celebrate the divine love between the gods Radha and Krishna. I found a seat on the wall that looked out over the river and the stage that was lit by electric umbrellas. The ceremony was in Bhojpuri, the native language of Varanasi, or maybe Sanskrit. There were at least 50 babas, some dressed in orange cloth and some naked. Midway through the music on stage and the roar of chanting, I saw Nagababa. He didn’t have his swing and was instead standing. His skin was white and streaked like forgotten strokes of sunscreen. His hair was swirled and nested on his head and his beard hung down past his belly and ended at his jungle of pubic hair. He had a miniature drum in one hand that he shook so the beads swung back and forth to make noise. In the other hand, he held a walking stick that for a moment I thought was wrapped with a snake. I refocused and realized Nagababa had pulled the shaft of his flaccid penis to stretch it several times around his walking stick so the skin was as flat as the mouth of an empty balloon. He was not alone, as each of the other babas twisted their genitals around some form of a stick. Where I expected to see Nagababa’s face holding agony, he was calm as if separated from his body.Was there some deity above holding an ethereal yardstick to measure their pain as their devotion? What the hell was happening?I had doubted Nagababa in his tent earlier that day, giving weight to judgment because he had a Facebook page. Assured of Nagababa’s commitment now, I felt disheartened about my role and assumptions as a tourist. Was I worthy of prayers from a man who sacrificed his body for belief? I felt puny in comparison to his physical devotion.

I refocused and realized Nagababa had pulled the shaft of his flaccid penis to stretch it several times around his walking stick so the skin was as flat as the mouth of an empty balloon.

I Learned About the Values of Intersectionality

My friend Navin once summarized being Indian as being a believer. “There are hundreds of Hindu gods who each serve a purpose, like bringing luck or fertility,” he said. “We don't have them memorized, but we know they’re there. I don’t practice as much anymore living abroad, but my nonna would sooner welcome me being Christian or Buddhist than an atheist. At least Christianity is believing.”Was having faith in India based on the act of belief rather than the subject of that belief? It took me being in Varanasi to value this concept of religious intersectionality and question my assumptions of worldly versus otherworldly. Homes in the city held both Christain crosses and Shiva sculptures. Wandering holy men sacrificed their bodies in the name of enlightenment but still posted on Instagram. I tried to bind faith exclusively to religion, a singular religion, because it's what I knew, but it didn’t fit India. I wanted to believe in the mala necklace Nagababa had given me. Maybe a rudraksha was just a seed. Maybe it would bring me divine luck. Either way, I liked how Navin saw it. “It’s better to not know but believe in something than it is to believe in nothing.”