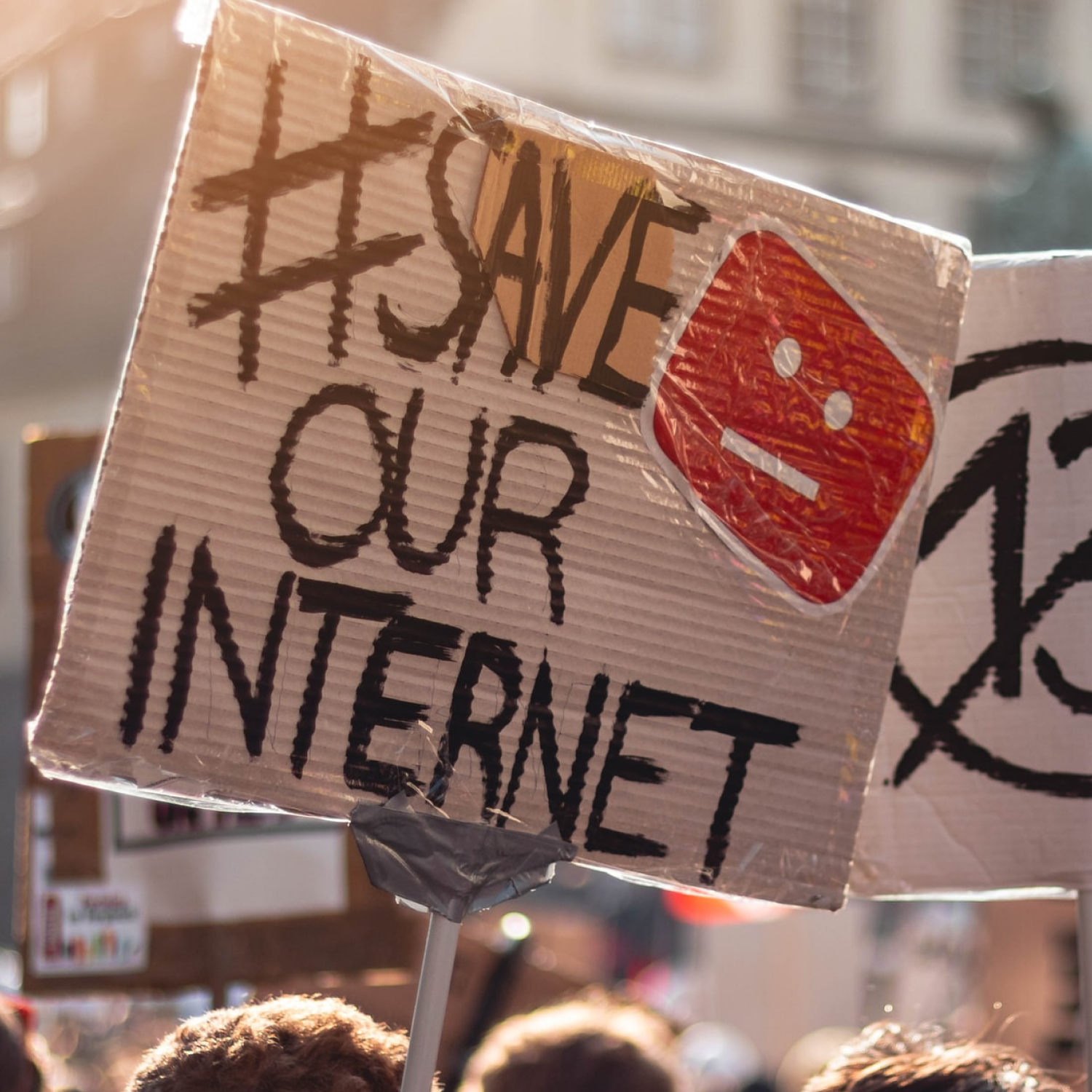

Why I Quit Social Media|A desert|Phone a friend card|A group gathered in New York City

Why I Quit Social Media|A desert|Phone a friend card|A group gathered in New York City

Why I Quit Social Media

The first time I remember vocalizing a concern about social media addiction was in 2014. I was in my therapist’s downtown Washington, D.C. office trying to explain the feeling that something had permanently shifted—not just inside me, but the world around me. I laid on a couch and tapped my sternum. “I feel something is wrong,” I said. “I stare at my phone for hours and it feels like I can’t stop.”In 2014, my cell phone was never far and my “real” social life was disintegrating. I was a librarian at an elementary school and my students required constant attention during the workday. I mostly kept my phone in my desk drawer, but the moment I had a break or was back home for the day, I was glued to it. My therapist responded to the concerns I was trying to express with a question: “What do you think this might be a coping mechanism for?”I didn’t have a clear answer. What was happening—this obsessive use that I struggled to break away from—felt larger than me. I was uncomfortable responding, as if I could identify a personal need I was seeking to fulfill and then develop a plan to eliminate or lessen it by myself, for myself, because of myself. Certainly, I knew what I wanted to escape—a stressful job, the loss of a long-term relationship, the subsequent cross-country move back East, the lack of a social life in a city that had changed since leaving three years earlier—but there was something outside of myself happening as well and I knew it.

A Documentary Gave Me a New Perspective

I have always been an online person. In the seventh grade, I taught myself HTML to make a Geocities fansite for the band Hanson. I regularly kept a Diaryland diary and then a LiveJournal. I was active on MySpace and Tumblr in their earliest days. But, before 2016, it still felt easy to disconnect. I could leave the computer and, later, put the cell phone down. Real life—life outside of a screen, with people and community in an accessible orbit where I could move, talk, learn and grow—was still more prevalent. I used social media with curiosity and imagination, with a desire to belong in a community while also expressing myself as an individual. My early Instagram grid contains no edited photos beyond the built-in filters. My posts are infrequent but contain snapshots from my life that I did not try to improve via caption or editing. I remember every detail of where I was when I took those first few years of photos. Over time, this eroded and turned into posting daily as some sort of proof that I had an interesting life, and one worth following. The personal significance of what I experienced and shared became much more focused on sharing what looked “interesting.” Beyond that, posting felt necessary and became compulsive—a dopamine fix.Any feelings or suspicions I had about why I struggled to put my phone away (and, perhaps more importantly, who or what was making it so hard) were confirmed by the 2020 Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma. I watched it over a series of four days, needing time to pause and reflect on its confirmations of things I had long suspected—that social media is reliant on “the gradual, slight, imperceptible change in our own behavior and perception” to turn us into a product. “Our attention is the product being sold to advertisers.” But what stuck with me the most was one line: “Social media isn’t a tool that’s just waiting to be used. It has its own goals, and it has its own means of pursuing them.” The apps I had once viewed as tools—ones that led to connection-building, unique expression and meaningful interaction—were completely compounded, manipulated and fractured by capitalism and commodification. When I finally finished the documentary, I put my phone into a drawer and took a long walk into the heat of the Mojave Desert, where I now live. I felt sick. Yes, I had many new people in my life because of social media. Yes, I felt seen in moments of happiness, peace and grief. But my life—my living—was taking place more on a device than out in the world with land and people around me.

Creating a Group Chat Became a Coping Mechanism

In a desire to get back to some sort of real and meaningful connection and community, I put out a call to my Instagram "Close Friends." Were there others who had watched the documentary and felt similarly ill? Were there those who wanted a total break and a group chat instead? I wanted out and away from an app that goaded me into excess and jealousy, feelings of self-doubt and unworthiness. Six people—all of whom I met through the very apps we were trying to escape—responded “yes.” The only “rules” were that everyone in the chat was bothered by the roles social media had begun playing in our lives. They hoped to have a space, and a group of supportive people, to turn to instead of using social media so frequently. Four of the six members, including myself, committed to only using Instagram once a week for one hour. I had an additional personal goal of only returning to social media when I felt I could “pop in,” catch up with friends and organizations, and then “pop back out” and into my real life. One member of our group is male; one is a female person of color; two of us are mothers; several of us are queer. Two members live in Portland, Oregon; one lives in Los Angeles; one in Chicago; one in New York City. We all do very different things for work. But we immediately and easily found commonalities and comradery. In the first few days of our detox, each of us reflected on the silly things we wanted to post (a good cup of coffee, a cute photo of a pet, a vanity license plate) and, eventually, the less-silly things we wanted to share. One member’s friend passed away from a battle with breast cancer and we had a lengthy conversation about grief, both offline and online. If K, one member of our group, popped onto Instagram to make a memorial post for her friend, could she continue to stay off? If she didn’t post a photo with a note about her death, would she look callous and uncaring to everyone in her life who was used to her honest and vulnerable posts? Each member expressed how much they understood this struggle with grief. We remained close as K attended her friend’s online memorial service. She shared her frustration with being unable to cry, and vented about the way the pastor was speaking about her non-religious friend.Another member of the chat shared that she had recently become pregnant again after a miscarriage. Few people knew about the miscarriage, and we, the members of the group chat, were the only people she was telling about the pregnancy other than her husband and toddler son. One member—also a mom—offered tips for morning sickness. We all shared our solidarity around what it means to be a woman carrying a life into this world. I imagined writing a vulnerable post about any of this to Instagram, and the people whose only response would be a double-tap of their finger on a screen. I realized that these likes had begun to feel more desirable and valuable than the continued, extensive support in the group chat. Within a week, I knew more about these five people than some of my oldest friends. I began to feel curious about this, too. Is this what we all craved when we poured hours into Instagram? To be seen— really seen—in all of our mess and struggles, our happiness and joys? Or was everyone in the group such deep empaths (and, we all are) that not having a place to share our most overwhelming emotions was unfathomable?

Limiting My Social Media Usage Is a Persistent Battle

In these questions, I felt a return to a before-time. Not before social media, but before social media became an obsession, a drug, an addiction. Here I was, asking questions, gathering information, finding breadcrumbs, reaching conclusions. With curiosity and care. It felt like coming home. The first two weeks I spent away from Instagram, in no unwavering terms, cleared my thinking. It made me more present, more curious and happier. When the familiar pull to grab my phone seized me, I still reached for it, but I reached for five people I knew and cared for instead of unknown thousands.When I logged back into Instagram after a two-week break, convinced I could just “pop in,” I did not pop. I stayed and I lingered and I fell back into the pit of scrolling. It was easy, seamless, comforting. I’m now waiting on a package to arrive from a company that makes time-lock safes. I ordered one with a white lid instead of a clear one that would allow me to see my screen through the plastic. I plan to put my phone in it for several hours a day, locked up with no way to escape other than to break the box open. I am curious if this is what it will take to stick.I told the group chat that I’m writing about them, about falling back into social media (four of us have returned to it), about this continual struggle that often feels maddening, embarrassing and out of our control. In return, they asked me how I’m feeling, what my plan for moving forward is, what support I might need. They mean all of it. They didn’t encounter any of my feelings through a brief, aimless scroll—they are invested in my life, and I am invested in theirs, in a way that feels solid and private and intimate.We have plans to meet in person, to rent a large house and cook and eat and dance together when/if the world allows us to feel safe again. In the end, I think that image—the six of us laying out on the floor in a shared physical space, unworried about our appearance or what we’re producing or not producing, unconcerned with capturing it all for the internet—is going to keep me off social media. We have a connection no app will ever help me understand or capture or feel.