My Mother and I Wait on New York’s Wealthiest and Most Famous Art Patrons|A movie theater worker enjoys the perks of seeing free movies.

My Mother and I Wait on New York’s Wealthiest and Most Famous Art Patrons|A movie theater worker enjoys the perks of seeing free movies.

My Mother and I Wait on New York’s Wealthiest and Most Famous Art Patrons

My mother and I create a diagonal line across Manhattan. She works on the Upper West Side; I’m on the Lower East. We are the custodians of two different theaters, looking after the city’s creative class in their pursuit of culture. Uptown, my mom is a matron for a hallowed institution of music, song and dance. You may be able to guess it. Downtown, I work in the box office of an art-house cinema. Most days, we cater to empty seats. Airborne viruses, streaming services and the hypnotic doomscroll have made our jobs nearly obsolete. We wait on standby for the stray customer. At night, we swap stories. These days, theaters stay alive by doubling as event spaces. Premieres are their bread and butter. This is when the funniest things happen, like the time my mom recognized Liv Tyler but couldn’t quite place her, so she asked her what she did. Actress or model? Being a 65-year-old woman, standing 4 feet 11 inches with a loose grip on the English language, makes it easy for her to get away with rudeness. Or the time I had diarrhea in the single-stall bathroom at a private screening moments before I directed Anna Wintour to use it. This is what's funny about living in New York: You live close by to everything you see in magazines and on TV. But also so far away.

Many of cinema’s greatest achievements depict the poor and disenfranchised, largely catering to an educated, affluent audience.

Waiting on Celebrities Isn’t Always Glamorous

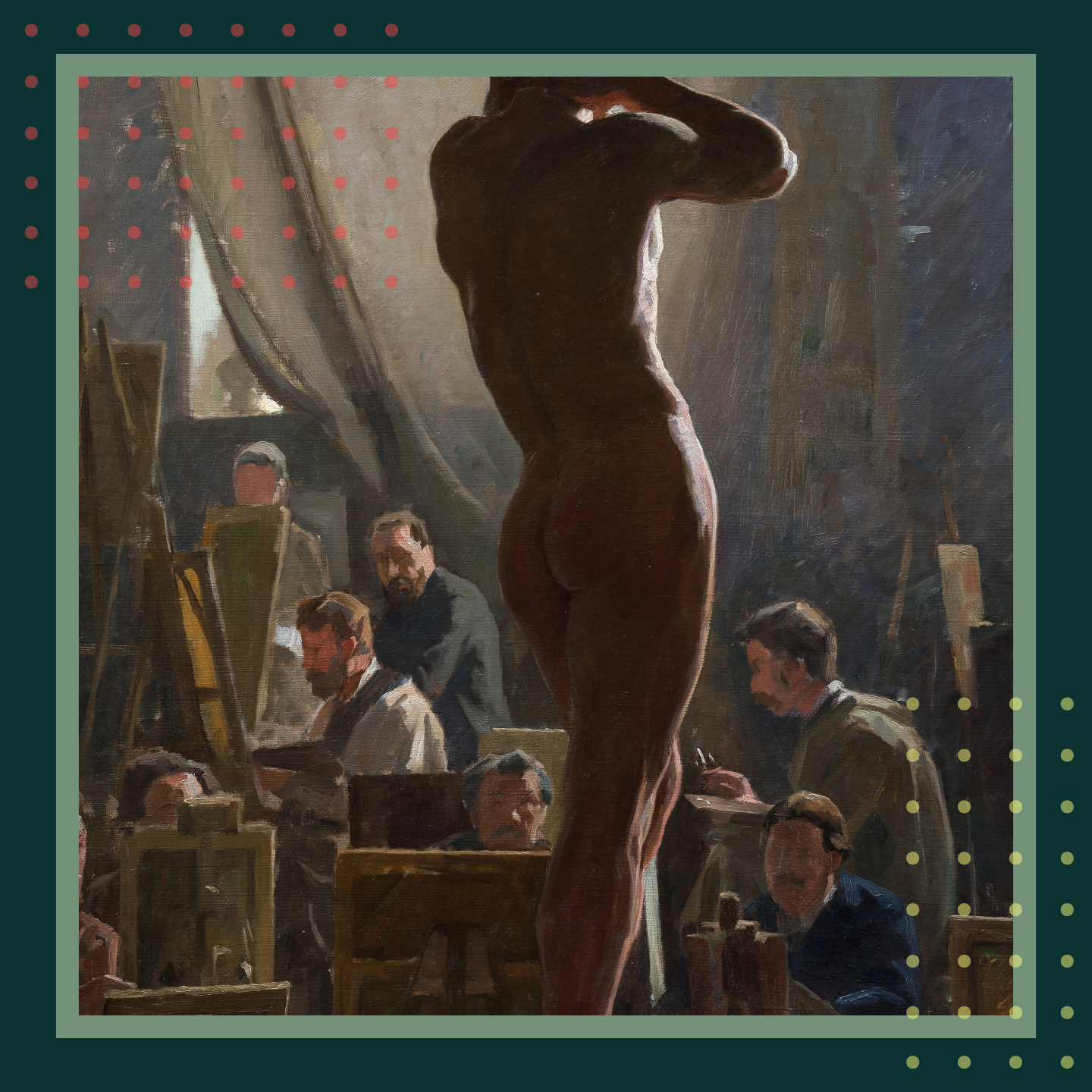

Of all the customers we tend to, celebrities are among the nicest. Their place in the hierarchy depends on the poor; they need our adoration. Like the time Zoe Saldaña gave my mom a kiss on the cheek for helping her with a dress malfunction in the bathroom. Or the time Maggie Gyllenhaal winked at me as I passed her a microphone at a Q&A. When rich civilians step out to see a movie, it’s also to display their wealth. The trust fund kids of today have dropped the “poor hipster” act of the past. Being rich is cool again. Oh, but who am I to make these statements about money? I’ve never had enough of it to know anything about it. One time, my mother found a gold ring in her bathroom and brought it home for me. I pawned it for groceries.Sometimes, I’m jealous. I wish I could own this person’s Rick Owens boots or that girl’s Prada wallet. I am not immune. What’s humiliating is that I would probably flaunt my wealth, too, if I had any. So if I can’t own beautiful things then I’ll look at beautiful things. A movie ticket is cheaper than a plane ticket. This is what drew me to movies first and, later, the box office. When you work there, movies are free. You can go anywhere you like, privately or with a companion. Even if you’re alone, there are other hearts beating along with you. I like facilitating this for others. The printing of tickets, the smell of popcorn, the sweep between the aisles as the credits roll. This makes it worthwhile. Until it doesn’t. Until you have to spend an hour’s pay on lunch. Until my mother’s tendinitis makes her feet swell from standing all day. Many of cinema’s greatest achievements depict the poor and disenfranchised, largely catering to an educated, affluent audience. The suffering of many becomes entertainment for the very few. It is called Art.Is empathy in movies a way to wash away class guilt? Maybe. Cinema is a medium that depends on compassion. It also depends on your looking away from the exploitation that seems to be inherent in filmmaking: The overworked and underpaid production assistant. The actor reenacting their trauma. The audience member who pays to watch. The box office employees with empty stomachs. The matrons who aren’t allowed to sit down.

One should only be sad when good things end.

Our Jobs May Not Be Fair, but Movies Still Are

Since starting this story, I’ve been fired for reasons that don’t fit into this essay. But if you Google "labor across theaters in New York," I think you’ll be able to guess why. I’m angry. I wasn’t the only one who was fired and definitely not the poorest. Although my bank account regularly floats below a hundred dollars, I have my mother. She tells me not to be sad. One should only be sad when good things end. She asks me to watch a movie with her to cheer me up. I find a torrent of Parallel Mothers, starring Penélope Cruz and directed by Pedro Almodóvar. While we’re watching, my mom tells me she was working the night it premiered and that she met Penélope in the bathroom. She told Penélope about the love we share for her films. Our favorite is Volver. Penélope squeezed my mother’s arm and said, “Hold on to each other.”