I’m a Jew Who Avoided Politics With My New Friends. Then I Got Invited to a Seder.

“Anyone interested in a Seder next week?”

The question was posed casually on a group chat of neighborhood parents. A couple of years before, I’d moved from Brooklyn to a less political, less Jewish town outside of New York City. I’d instantly bonded with these people, mostly because we lived within blocks of each other and had similarly-aged babies. In those crucial early days of parenthood, having a tight-knit community can mean the difference between sanity and soul-crushing despair.

In some ways, there was a lot of intimacy between us. We’d swapped babysitting nights, recs of fun spots around town, and tips on how to soothe hand, foot, and mouth disease (if you know, you know). But in other ways, these people were still mysteries to me. For example: As a Jew who has long called for a free Palestine, I wasn’t quite sure where many of these parent-friends stood on the war in Gaza.

Suddenly, I felt hesitant about attending this Seder. Because, to paraphrase the haggadah, this Passover was different from all other Passovers.

I’m proud of my Jewish identity, but it never had much to do with Israel. My ancestors came here decades before its founding. My family was not religious, but rather “culturally” Jewish. To me, my Jewishness always had more to do with bagels and sour pickles; the Catskills and the Lower East Side; and most importantly a strong sense of social justice and allyship. The elders around me were Bernie Sanders types; they had deep roots in leftist movements and activism.

When it came to Israel, most Jews I knew were ambivalent at best, intensely critical at worst. When I traveled to the country on a Birthright trip in college, the organizers’ insistence that we were the “chosen people” and that Israel was our true home felt strange and icky. I had always been taught that everyone was equally deserving of freedom and happiness. Daily life in Gaza and the West Bank—which I learned more about on that trip—seemed to fly in the face of those values.

A Seder, in its classic form, is basically Zionism the holiday. My easy, breezy friendships were about to get real.

After Birthright, Passover got a little weird. My family had always had a pretty standard Seder; we dutifully read an old-fashioned haggadah with no real discussion of what Israel meant to us or to the world. I felt increasingly uneasy about retelling the story of Jews’ oppression and arrival in the “promised land,” when Israel was currently oppressing another group of people to declare ownership of that same land. At the tail end of my twenties, I started going to Seders that acknowledged this painful irony and called for liberation and peace for all.

Still, I was never deeply involved in Middle East politics. Despite my view that Israel’s policies toward Palestinians were unjust, the broader issue felt complex and inscrutable to me. Mostly I didn’t think about it. That changed after October 7. I was aghast at the deaths and kidnappings wrought by Hamas, but then my thoughts were overtaken by the unthinkable bloodshed, hunger, and destruction in Gaza. The power imbalance and sheer difference in scale erased any previous reluctance to speak my mind. I had a clear-as-day, gut reaction that has only grown stronger as the war destroys more lives: No, no, no. Not in my name. What Israel was doing to Palestinians went against everything I stood for as a Jew and a human.

I talked about Gaza constantly with my more explicitly political friends from the city, and I posted about the situation freely on social media. But it seldom infiltrated in-person reactions with my new pals. Now I was getting invited to a Seder—which, in its classic form, is basically Zionism the holiday. My easy, breezy friendships were about to get incredibly real. (Let’s face it: Jews are intense!)

I was torn about the best course of action. Should I find out the host’s Israel-Palestine politics beforehand, or just go and hope for the best? While supporters of Israel’s military actions made me incredibly angry, I was almost more offended by the idea that a Passover could be conducted apolitically in 2024.

Eventually, I figured that if I was going to have authentic, meaningful relationships with any of these people, I had to speak from the heart and hope they’d accept me. I had to believe that my friends were generous, curious, and kind. I called up the host—an incredibly sweet woman (I’ll call her Olivia) with whom I aligned on countless issues, from abortion rights to childcare collectives—and explained that I was wondering how the war in Gaza would be handled at the Seder.

It was a conversation Olivia was not prepared to have. She hadn’t planned to mention the conflict at Passover—though she was mulling a second empty chair representing the hostages and a second serving of bitter herbs on the Seder plate. She told me that for the last six months, she’d been mostly preoccupied with the rise of anti-semitism and the experience of being a Jew in the U.S.

It was a Twilight Zone moment, the kind when you realize that someone who’s similar to you in so many ways had been seeing the world through completely different eyes. I began questioning my life choices: How could you have moved here and made a bunch of friends who don’t hold your same values, who don’t care about politics the way you do, who prioritize their own emotional comfort over those who are gravely, urgently, and unfairly in danger—just because you were a lonely mom and they had babies, too?

I went ahead and explained my perspective. Olivia listened. She didn’t get defensive. When I asked whether there’d be room to discuss our feelings about the war, she was open to the idea. “I’ll have to reflect on all of this,” she said. There were awkward, halting moments, but it was by far the deepest conversation we’d ever had. Her humble tone convinced me that my family should go. Maybe it would be useful and even constructive to venture outside my own bubble.

A few days later, Seder night arrived. At first, the kid cacophony drowned out any discernible vibes between the parents, which felt like a telling metaphor. Would we even have a quiet moment to discuss any of this, or will we spend the whole night reining in our toddlers? I wondered. But then the kids settled down, and we sat around the table. There was an extra empty chair. There was an extra pile of magenta horseradish on the Seder plate. And then I saw it, right next to the chicken bone: a wedge of watermelon.

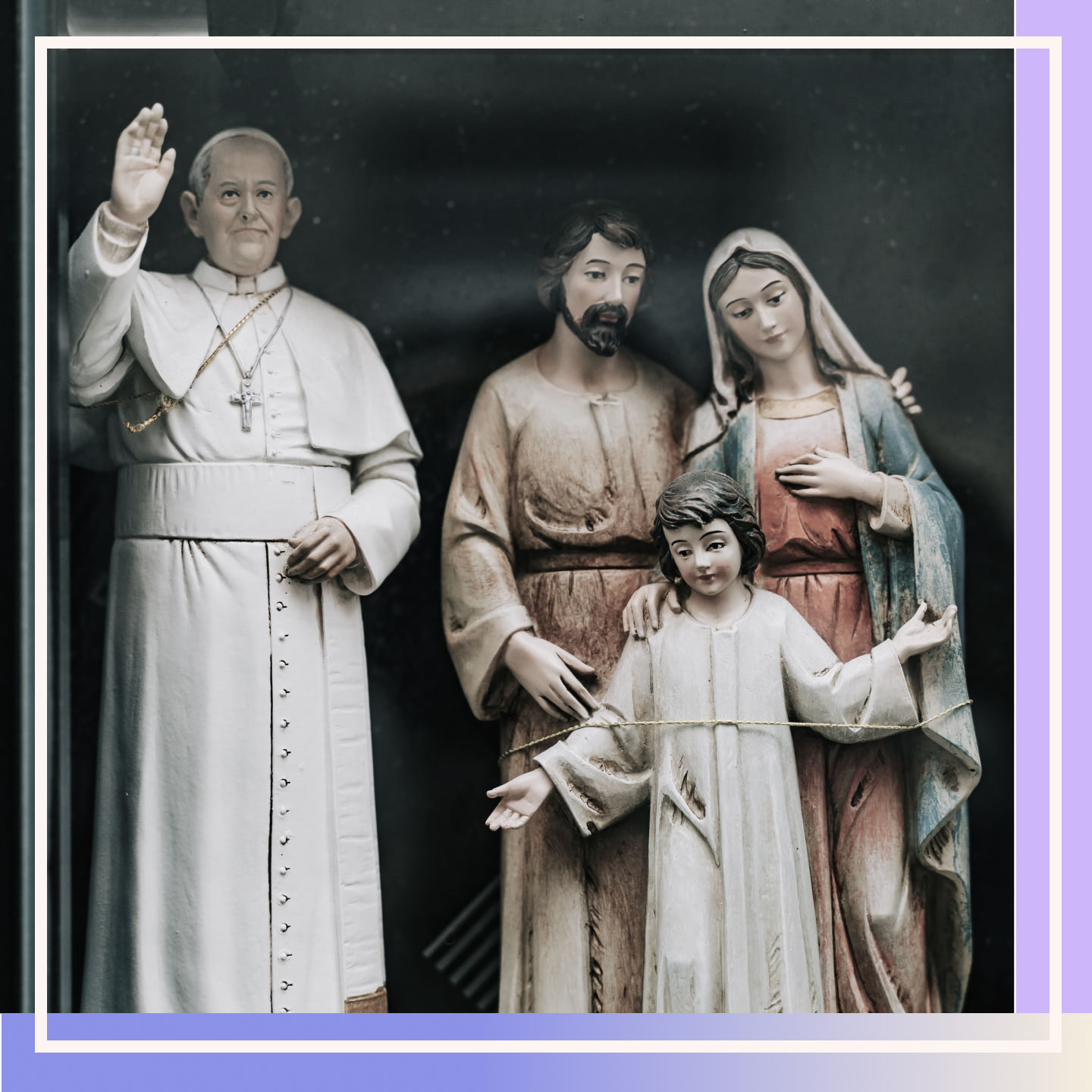

Since 1967’s Six-Day War, the watermelon has been a symbol of Palestinian solidarity, and images of them have proliferated on social media in the last few months. When cut open, the fruit exposes the colors of the Palestinian flag—red, black, white, and green. It was enough to help me relax at the table, but Olivia’s Seder went beyond symbols. After the Four Questions, our kid-friendly haggadah included a new, fifth question: “How does Passover feel different this year?”

We all went around and said a few words, some people sticking to personal details like “I’ve never done a Seder with my child before” and others nodding to the political situation in various ways. I said that it felt wrong to center our ancestors’ pain while some of their descendants were inflicting so much, that it’s because of my Jewish identity that I protest violence and war tonight.

It was all very gentle, careful, and often coded. Certainly not the same as, say, the Seder I attended in 2018 that featured the Jewish Voice for Peace haggadah. The sense that these weren’t 100% “my people” still lingered and probably always will. But I felt listened to by my community, and there was a new level of connection between us—one that extended beyond our shared experience as parents.