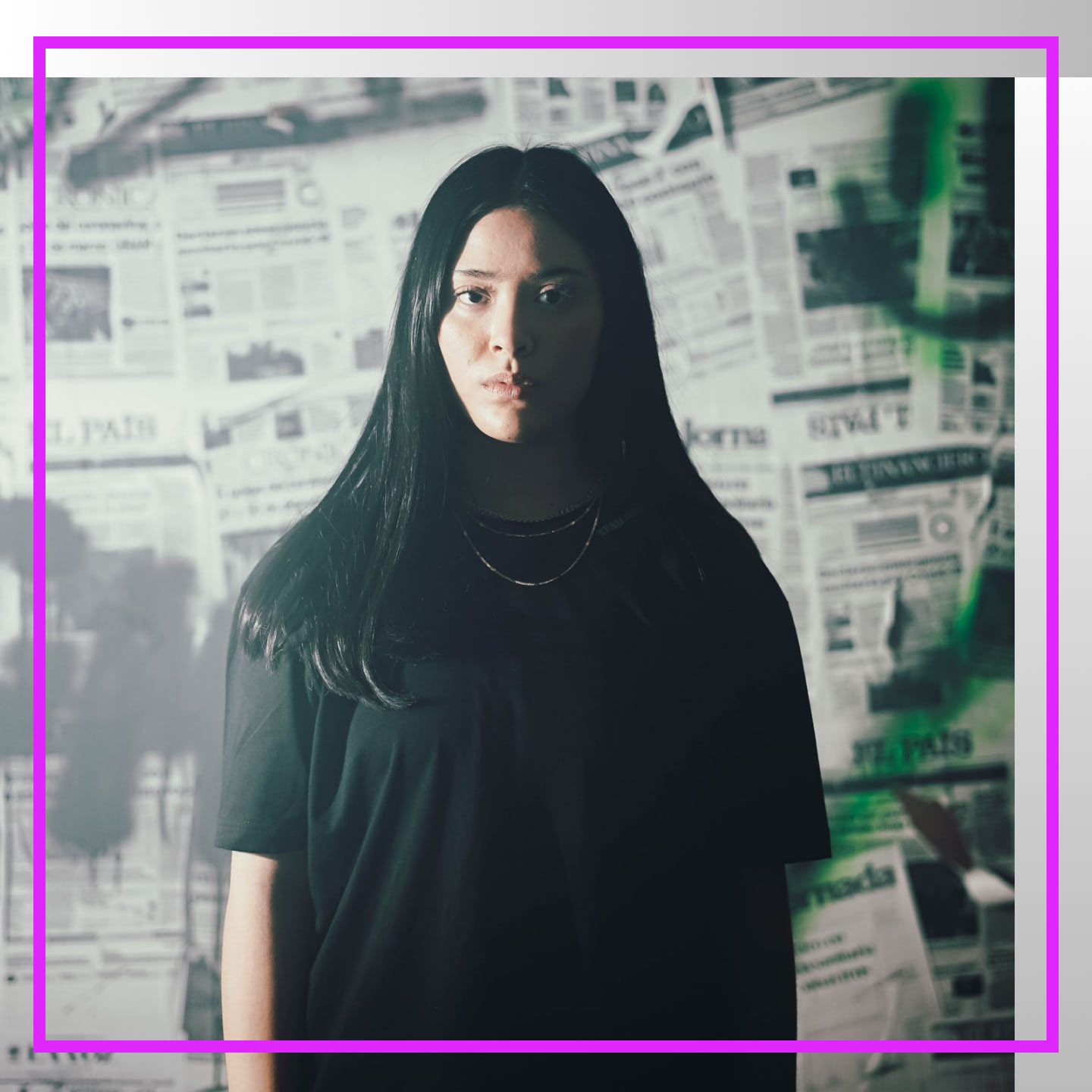

I Was the Only Writer of Color for My Website; Then They Fired Everyone But Me|The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 changed the conversation about race in America.|A Black female writer enjoys being a part of a progressive, inclusive staff.

I Was the Only Writer of Color for My Website; Then They Fired Everyone But Me|The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 changed the conversation about race in America.|A Black female writer enjoys being a part of a progressive, inclusive staff.

I Was the Only Writer of Color for My Website; Then They Fired Everyone But Me

The summer of 2020 has become couched in euphemism. While it was the first “COVID summer,” it was also the summer that catalyzed a wave of racial conversation after the murder of George Floyd. Soon, the news became saturated with reports of police violence and protest footage, and social media was flooded with pictures and promises to push for collective action and change. Though these images weren’t new, there was something different in the momentum garnered by this wave of protests. The conversations didn't stop after a week passed, and, for once, even mainstream rhetoric went past the usual platitudes. Instead of shallow takes on racism, the conversation pivoted into bigger topics like institutionalized racism, unconscious bias and the complicity of white Americans. Finally! This new energy was exciting, and it defined the summer. Everybody’s sentences began the same way: “With everything happening around George Floyd” or “The whole thing with Black Lives Matter,” but this time, the euphemisms signified bigger change. Even Angela Davis called it "a very exciting moment," saying, "I don't know if we have ever experienced this kind of global challenge to racism and to the consequences of slavery." For many Black people, these conversations were long overdue and the calls to center Black voices and “pass the mic” led to Black squares on Instagram pages and pledges for all corporations to do better in terms of diversity and inclusion.As a young professional trying to navigate the Covid-employment landscape, these conversations were encouraging. I’d gotten used to dealing with racial microaggressions before, with years of education in predominantly white institutions leaving me jaded, nihilistic and, at my worst, cripplingly depressed. But suddenly there was hope, and I could see it. Jobs I’d applied for months prior finally called me back—my ethnic name was no longer a detriment, but suddenly an asset—and opportunities to tell my story, and be heard, were almost too bountiful to be believed.So I jumped at them. In conversations I’ve had since, many of my Black friends and peers describe that time as a strange mix of validation and anxiety, at once feeling relief that we were finally being listened to, even as we looked over our shoulder, expecting the other shoe to drop. But while it was good, it was good—and I was going to grab the opportunities as they came.

I was going to grab the opportunities as they came.

The Company Went All-In on Anti-Racism Education

Soon, I accepted a job as a “BIPOC Staff Writer” at a digital media company. It seemed like the perfect role: I’d actually be encouraged to write about Blackness and Black representation in media and pop culture.The company expressed its commitment to “anti-racism,” because that was the buzzword at the time. It effusively promised me the freedom to express myself as a writer, and support to grow in my career. The organization shared a commitment to growth on their end, too. It implemented regular anti-racism meetings, a focus on diversifying sources, encouraging further anti-racism education for the staff, executive team training and more. And yes, it knew these were lofty goals, but it was committed to reaching them. As a media company, it said, it had even more responsibility than anyone to commit to intention and education. And it was determined to make that commitment.For a while, it was as good as it seemed. My team was full of other young, like-minded writers, all invigorated by the air of change—both in a wider societal context and within the company. People first, they said, not profit first. Though I was only one of two Black writers, I felt welcomed by the team and excited by the energy.As I got acclimated to the work environment, I learned more about the company itself. My side of the company was just a smaller part of a larger agency. We had relative freedom, sure, but there was the implicit understanding that we were there to direct traffic to the website. My coworkers and even my managers would unashamedly roll their eyes and say snide comments about our parent company.This clear divide was on display during our infrequent meetings with the other side of the team. While my managers did their best to emphasize the work we were doing and the direction we were moving, the other side just wanted numbers: more clicks, more money. Still, the surprising momentum for anti-racism and social change buoyed our content. Our mission was aligned with the trends, so everyone was happy. But by the time I’d stopped looking over my shoulder, the shoe finally started to drop.

After Social Justice Movements Waned, My Role Pivoted Into Ad Writing

It started with “budget cuts.” After President Biden’s inauguration, the energy for radical change began to die down. With no incendiary comments coming from the White House, and following the void of drama after the insurrection, political news didn’t compare to the Trump era. The public’s social fervor waned.Suddenly, my managers were meeting with the business side of the parent company more and more frequently, and our jobs were starting to change. Our freedom to pitch and write our own stories waned while more and more assigned advertising content appeared on our rosters. I could deal with this. There were more eyerolls, more sighs and snide comments, but we still had our team.Until we didn’t.It happened at 1:03 p.m. on a Friday. I was in a routine meeting with my manager when the company broke the news that half the team had been fired. We didn’t know the state of our own jobs, and instead of answers, all we heard was the repeated refrain: “budget cuts.”Almost overnight, everything changed. Over the next few weeks, we transitioned almost entirely into ad writing. Though we didn’t have the same momentum we had during the pandemic, our sites were still doing well. Yet, we were still given no explanation for the changing state of things. One second I had a dream job, the next I was stuck in an unrecognizable shadow of that former role—writing ads for brands I didn’t use.For a while, I thought it might be temporary. Maybe, I reasoned, once things calmed down, we would get answers and I would go back to the job I signed up for. In reality, things didn’t settle down. They escalated. Instead of going back to normal, my job officially shifted to branded content rather than the organic, politically-driven stories I was enticed by the promise of writing. And just when I thought this was the end of it, the remaining few members of my team were let go and the ones that weren’t quit.Suddenly, there was no creative, passionate team of writers. It was just me, alone, working alongside the team we used to roll our eyes at—with none of the promises of my job title in sight. How did I get here? Doing a job I didn’t sign up for, stuck in the same kind of toxic, profit-first environment I thought I was escaping?

Companies use the rhetoric of diversity and inclusion to entice Black talent, then parade them like trophies without actually valuing them.

BIPOC Inclusion Is a Fleeting Idea

In truth, I shouldn’t be surprised. My career trajectory followed the thing that sparked it. When Black stories were prioritized, I felt like I was at my peak, but as the fervor from the summer faded, social commentary was less in demand and so I was, in effect, obsolete.I’m sure I’m not the only one. This kind of cycle is in keeping with the more widespread media trend of Black employees becoming the voice of a company only when it’s profitable. For social media clout, for diversity specs or to keep up with whatever is in vogue, companies use the rhetoric of diversity and inclusion to entice Black talent, then parade them like trophies without actually valuing them.As the only remaining writer on the whole team, my company got to keep their “BIPOC Staff Writer” in title, but turned me into a workhorse, churning out content I never signed up for. And now that the desperate calls of media companies seeking Black stories to “pass the mic” have quieted, where else would I go? So I stay. Any other company would almost undoubtedly treat me the same.