Photo by Furkan İnce on Pexels.com

Photo by Furkan İnce on Pexels.com

Ketamine Therapy Healed My Depression. Until It Didn’t.

I came to ketamine therapy out of desperation. I was 35 and had already sampled a buffet of treatments for depression – antidepressants, Freudian therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, yoga, meditation, diet, group therapy, and even LSD. Some of these treatments promised immediate relief, and often delivered. But over time, with the stressors of modern life pressing on the walls of any serenity I’d strained to earn, the effects wore off and the depression returned. There was never a silver bullet, but I was determined to find one.

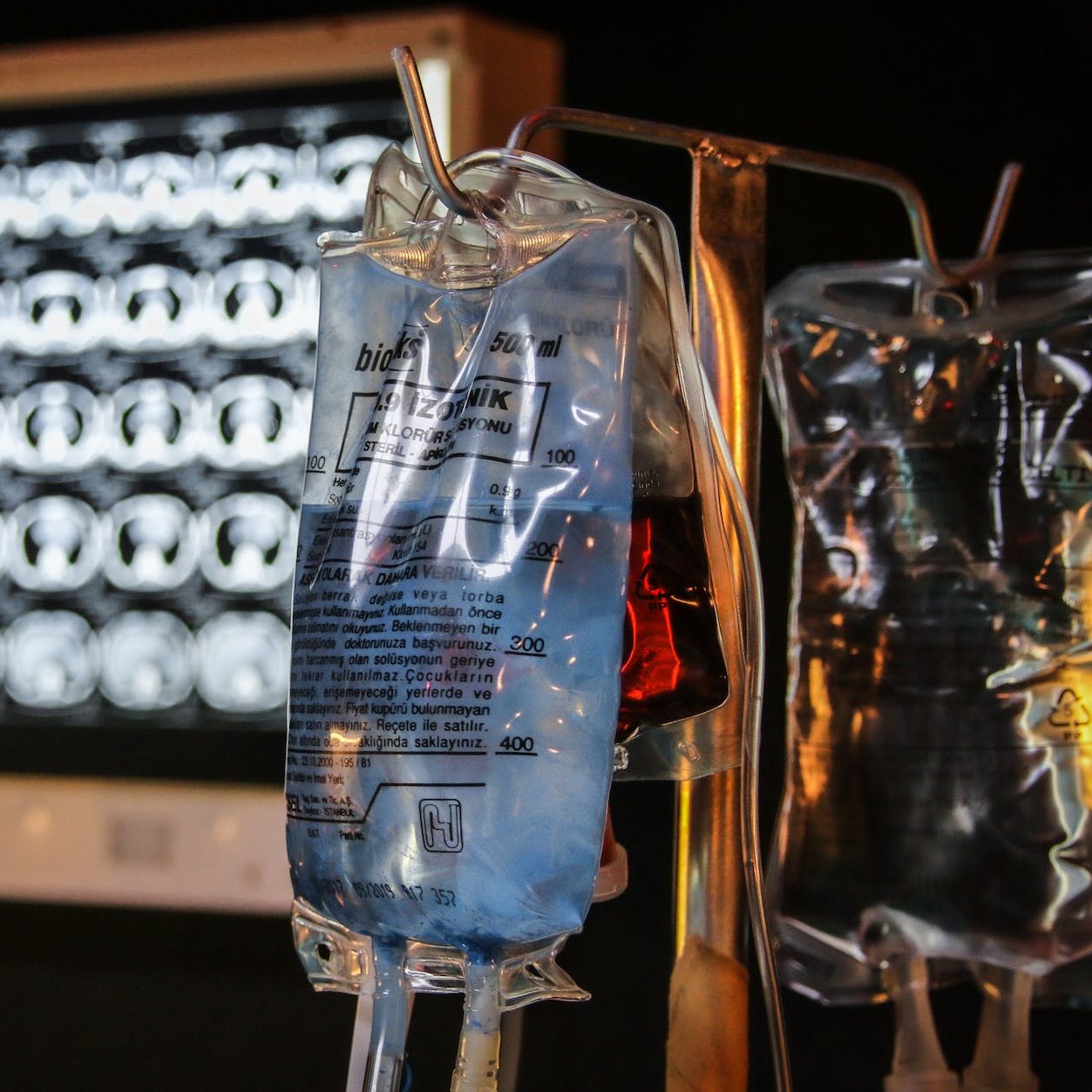

This was how I found myself in a Chelsea office room with the lights dimmed, while a soft-spoken, middle-aged female doctor inserted an IV into my left arm and asked me if I’d like to listen to “classical or soundscapes.” I’d never taken ketamine before. I’d only ever associated it with raves and after-hours parties. Oh, and medical treatment of farm animals.

“Isn’t it, like, a horse tranquilizer?” I asked a friend who took it recreationally.

“Not really,” he said. “But k-holes are fucked up.”

Ketamine is a dissociative drug and, in fact, is sometimes used to tranquilize animals. A “k-hole” is street slang for when the trip becomes so intense that you lose a sense of your own body within space and time. Depending who you ask, k-holes can be a technicolor dream ride or an all-encompassing hellscape.

But the recent medical research on ketamine as a treatment for depression was promising, even if the doctors behind it admitted they weren’t completely sure why it was working. There were more than a few companies offering treatments across New York City when I began my search in 2022, but many put little to zero emphasis on post-session talk support. I chose my facility because they required all patients to have regular access to their own therapist (with whom they communicated results). Plus, they had a sliding scale.

“Think of ketamine like a Zamboni,” one of their doctors told me over a phone consultation. “The drug smooths out your brain and makes it more receptive to developing new pathways.”

When I tried to steer, the sessions often turned sinister. When I released control, I drank the entire universe.

I’ll admit, the hockey analogy got me. The thought of smoothing over the depressive neural pathways that made my daily life feel like I was wearing ankle weights was actually erotic. This could really be it.

The protocol called for four treatments in two weeks. The on-site doctor would accompany me in a private room equipped with noise-canceling headphones for calming music or soundscapes, eye covers, aromatherapy, and a reclining chair. The drug would be injected intravenously, with dosages measured based on my body weight to ensure safety. I’d be monitored the entire trip. The week before starting, I’d begun having suicidal ideations–a frequent element of my depression–so I went into treatment with blind enthusiasm. I needed results because I needed to want to live. Bring on the Zamboni.

During my first session, I listened to tropical forest sounds, my mind bouncing from thought to thought, trying not to force any outcome as the drug entered my bloodstream. After what felt like 30 minutes (it was probably about 10), the blackness gradually transformed into a prism of stars, then a river carrying my weightless, floating form into a tunnel of light. I watched my body turn into seedlings, sprouting roots and emerge as a tree under a cloudless blue sky. Each time I tried to grasp what I was experiencing, the images would whoosh and transform. My inner voice felt like it was strapped to a gurney. I was, in effect, paralyzed and mute to the cosmic whirlpool inside my own head. And I loved it.

When it was over, I noticed my right hand was pressed against my heart.

“You had it there the entire time,” my doctor said.

I left the first session still groggy, the landscape of New York pulsing like thousands of heart ventricles. My vision seemed color-corrected. The heaviness I’d carried that morning had evaporated as if placed under strong sunlight. On the subway ride home, I cried.

The remaining sessions were a roulette of interstellar awe and grueling darkness. One moment I was riding the galaxy on a rainbow gondola, the next I was facing my uncle James who had killed himself when I was a teenager. No image, no experience lasted more than the span of a completed thought. Nothing could be grasped. Very little made sense. When I tried to steer, the sessions often turned sinister. When I released control, I drank the entire universe.

After the fourth session, I felt the arrival of a distinctly foreign energy: hope. My doctor reminded me that for many, follow-up sessions were necessary maintenance, but focusing on healthy habits to establish new neural pathways was elemental. The treatments were only a catalyst. The rest was up to me.

I only half-listened. After all, I had the ultimate buffer against relapse: Zamboni brain.

I was back for a follow up just three weeks later. A family conflict triggered my old responses of doom spiraling and I’d fallen hard. I took the injection, floated into the astral plane, and emerged bleary-eyed and renewed, convinced that this time the sensation would last forever.

Then more stressors came. A job loss. A conflict with my partner. The onslaught of violent daily news. The depression crept in like smoke under a hallway door, slowly overtaking my life until it was suffocating me. I tried a few follow-up treatments, but grew frustrated at the diminishing returns. This depression would never be over, I realized. Clearly, ketamine failed me. I never went back for more treatments. Fuck the Zamboni.

Then, a few months after my final session, I found myself shifting elements of my life to focus on mental health. I made efforts to spend time with friends, moved my body daily, danced, listened to cheesy ‘80s pop hits, journaled, and continued in therapy. I sought out connection and inspiration rather than unending joy. When I was down, I admitted it openly to myself and those I trusted.

I realized one morning that I hadn’t thought about killing myself for six months—since the day of my first treatment. A personal record for me. I actually wanted to wake up every day and see what happens next. Even on the dark ones.

The doctor’s told me from the beginning that ketamine was only a tool, but I’d ignored them. They never promised a “cure”–just the possibility of reshaping the mind. And hell, learning to want to live again seems like a promising place to start.