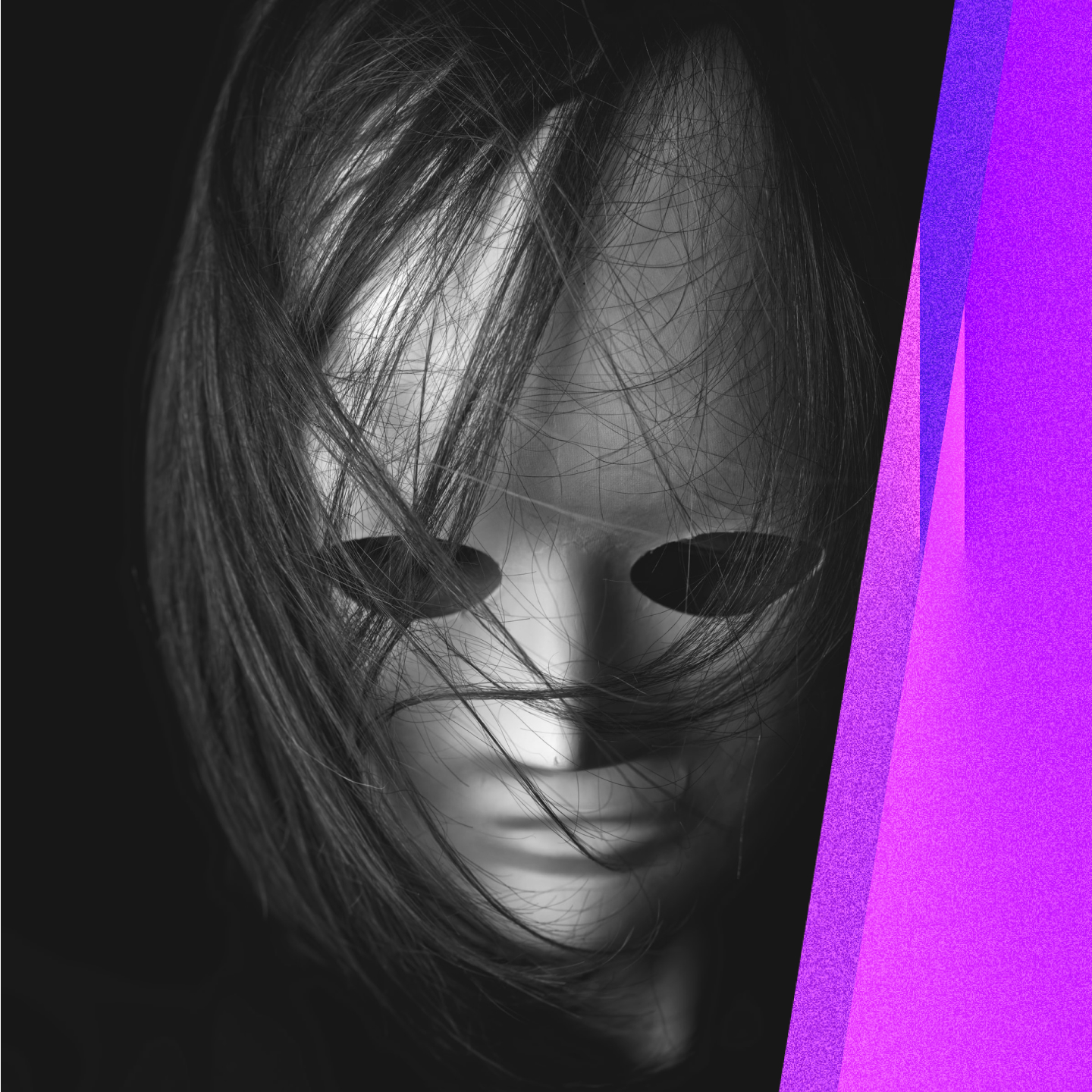

The Fashion Industry Burns Out Its Best Young Talent|Working in the fashion industry is non-stop abuse.|The fashion industry is trial by fire and often leads young talent burned.

The Fashion Industry Burns Out Its Best Young Talent|Working in the fashion industry is non-stop abuse.|The fashion industry is trial by fire and often leads young talent burned.

The Fashion Industry Burns Out Its Best Young Talent

I moved to London to study fashion when I was 18 years old. I ate nothing and spent whatever little money I had on cigarettes, coke, clothes and shoes. I slept little and passed out in clubs. While all these would have made me a hot mess in nearly any other situation, by the standards of the fashion industry and art university, I was simply living the life. I was it–getting photographed by street-style photographers, cutting queues and being embraced by the fashion party scene. I had so many pairs of shoes that the floor of my dorm room was barely visible. I looked good.

We Lived—and Suffered—for the Glamour

And looking good was the one thing that mattered. That I was battling an eating disorder or so poor I had to steal a single chocolate from a box left on the floor of my building just to function didn’t seem like that big of an issue. It didn’t stop one of my friends from loudly declaring that if he had to be a girl, he’d want to be me. It didn’t stop me from really thinking that I had the best life, even as I was cutting classes due to being physically unable to get out of bed or repeatedly smashing a club’s toilet to pieces with my heels because my friends and I stupidly dropped a bag of “something” (we weren’t sure what, but we still took it) behind it.Our lives were a whirlwind of clothes, drugs and glitter, and as the bright young future of the fashion industry, we burnt brighter and faster than anyone else. Getting the flu after a game of spin the bottle with a bunch of models in the middle of a club was a badge of honor. Looking back, our complete disregard for our own health and safety was worrying. We stumbled around London on sky-high heels and obsessively compared our BMIs. Years later, one of my best friends casually mentioned she “suspected” I had an eating disorder. She didn’t say anything at the time—“You looked so good!” After a couple of years of this, I had “made it”—that is, I was attending fashion weeks. I still had no money, and I was still a student, but I knew anyone who was anyone and had upgraded my fashion closet to designer.Then, at the grand old age of 24, I gave up. Surviving on fantastic fashion and smoky air wasn’t sustainable, but it took going into business with someone who was more messed up than I was to finally break me. I started a fashion magazine with a girl who spent days on end in bed, got into a random van because it was going to a “party” and brought a drug dealer to spend the night in our flat. It took all of this for me to look at my “partner” and snap—this wasn’t what I wanted.

Getting the flu after a game of spin the bottle with a bunch of models in the middle of a club was a badge of honor.

My Professional Life Was Nonstop Abuse

The fashion “industry” isn’t so much an industry as a flame that attracted us with its tales of fabulous parties, fabulous people and incredibly fast lives and then burned us up. We didn’t get paid and we were bullied constantly, made to prove ourselves over and over and always found wanting. Wearing the same shorts twice was cause for sneering comments. During Paris Fashion Week, I had to run around to find deodorant because someone told me I smelled. Having to ask models in a showroom if they could spare some perfume was a low point. “Oh, you look good…today.” Over and over, I brushed it off. Over and over, I pretended it was funny. After all, by that time, I was getting paid—if not well, at least enough to buy cigarettes and a couple of gin and tonics. Doing bits and bobs here and there, PR work and assisting in a showroom wasn’t glamorous, but it was still fashion. My bosses would invite me to parties, pass me poppers and then ignore me for the rest of the night. Then they’d call me months later to ask if I knew where some clothes that had gone missing had gotten to. “It’s OK if you took them, but we need them back.” I didn’t steal those clothes. I also never heard from them again. An editor who continuously compared me to his girlfriend would happily tell me that I did everything wrong, even when I used my contacts to get him into a show. “You should eat something,” he told me, quickly followed by, “Oh dear, the cheese, really?” and a little laugh that still keeps me up at night. The days I wore flats, I was told to wear heels, and the days I wore heels, I was told to walk faster. “You shouldn’t wear heels if you can't walk in them.”

Within the creative industries, fashion wins—at being the worst paid, the most shallow, the most divisive and destructive.

I Miss Fashion, but I’m Never Going Back

And yet, I loved it. I loved my heels, I loved the parties, the shows and yes, I even loved the bitchiness and the bickering. The fashion world celebrates its bright young things, destroys them and builds a shrine to them for the next crop to worship. It teaches us all that this is what we should aspire to: dying young and fashionably. The frenetic pace we lived at made the industry go round. But as much as we thought we were in and as much as we wanted to belong, we somehow never really got our big break. We didn’t keep in touch. Everyone went their separate ways, and whilst we all somehow still have ties to the industry, none of us ever connect. The fashion industry isn’t the only industry that mistreats its young talent this way. As a journalist, I transferred my skills to the music industry and it was much of the same: no pay (or getting paid in “perks”), smoky, boozy, insanely unhealthy. This is the cost of creativity, apparently. But at least you could eat and my mental health didn’t suffer as much. No one was criticizing me at every turn, nobody gave me “compliments” that made me want to dive headlong into the Thames or puke my guts all over the floor. If anything, other industries could teach fashion a thing or two: You don’t have to lose your craziness and creativity, your fast pace and party-throwing to be decent. You can ask somebody, “Are you OK?”—and mean it—and still be at the top of your game. You can rise without pulling everyone else down. Within the creative industries, fashion wins—at being the worst paid, the most shallow, the most divisive and destructive. It also wins at being the most interesting, the most fast-paced and the most fabulous. It might be a turd wrapped in glitter, but it’s still sparkly. It’s an unhealthy, schizophrenic environment that hooks you like crack and spits you out the minute you start questioning it. I still love it. I sometimes even think I might miss it. I don’t miss the eating disorder. I don’t miss the constant put-downs. I miss the sense of belonging, the incredible parties, the great clothes and the knowledge that there is always something to dress up for, even if it’s just popping down to the off-license (you never know who might be watching). As I write this in the most boring and unfashionable clothes you can imagine (working from home in the middle of a pandemic doesn’t really call for couture), I feel a pang of longing for the fashion industry but not because I ever want to go back to it. I miss it because I realize this was such a big part of my life. Fashion made me who I am today and I will forever be grateful. I fell into journalism by accident, and it’s fashion that I have to thank for my current career. But make no mistake: I’m glad it’s behind me.