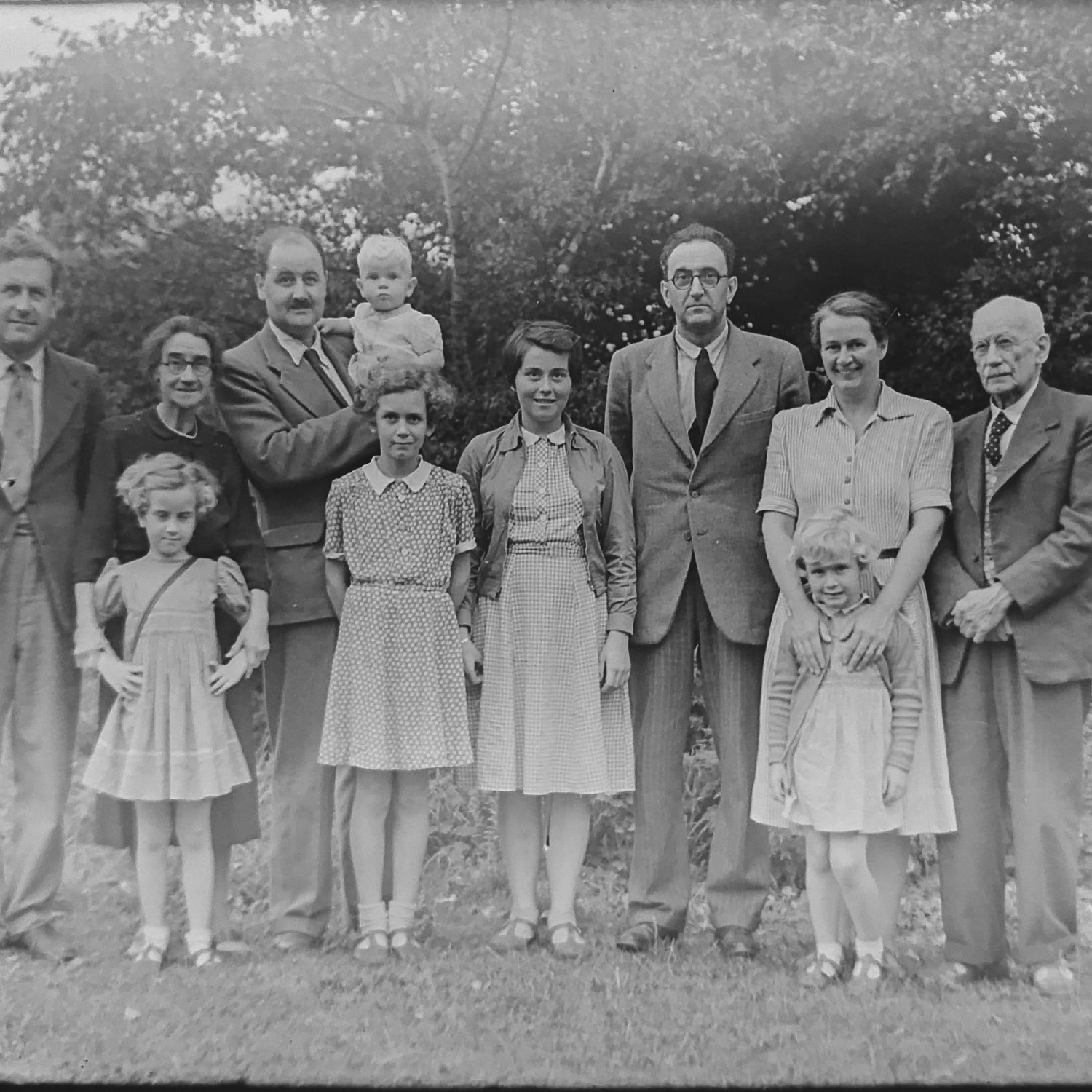

I’m A Descendant of Slaves and Slave Owners|Historic handwritten papers and yellowing black and white photographs.|Large, exposed tree roots.

I’m A Descendant of Slaves and Slave Owners|Historic handwritten papers and yellowing black and white photographs.|Large, exposed tree roots.

I’m a Descendant of Slaves and Slave Owners

“Statistically insignificant.” That was my sister’s response when I told her that my DNA test revealed that I was three percent West African. I thought she’d be surprised or shocked. I didn’t expect sangfroid. Being a person who’s always been interested in genealogy, I was anxious to research my roots and find out if there was any evidence of this “insignificant” drop of African blood in my family’s history. Before climbing every branch of my family tree, I thought I’d ask family members if they knew anything about any rumors or stories of Black ancestors. That was a mistake.My father died several years ago and his sister is his only surviving family member. Let’s just say she didn’t rejoice at the news of our expanded ethnicity. “There’s no way we had slaves in our family!” my aunt barked.“I didn’t say they were slaves,” I replied too meekly.“Well, they were Black, so what do you expect they were?” she said, obviously finished with the conversation.

That was a mistake.

My Ancestors Saw People as Property

Hanging up, I thought about what she said. I knew that on both sides of my family there were slave owners. I don’t like writing those words, but I don’t like running from it, either. I have a copy of my tenth great-grandfather’s last will and testament wherein he bequeathed a “negress named Diana” to his daughter and her husband. When I found that will and read that clause, I winced. I didn’t want to think that someone known for having fled England for the purpose of freely practicing his concept of Christianity would not only presume to own another child of God, but to hand them down like property to his posterity. But there it was in black and white. I dealt with it by focusing my genealogical endeavors on my numerous indigent ancestors, most of whom were treated by landowners as little more than chattel themselves. That didn’t make them slaves, though, and I was determined to find out if the West African component in my DNA came from enslaved people.It does.

I Discovered the Roots of My Family’s Names

The last name of tenth great-grandfather and -grandmother was Yoconohawckon. To me, that surname sounded Native American, and I found out it was, but it was used by a married couple held as slaves in Virginia. What follows is a summary of my research written by a distant relative who has spent decades studying this remarkable couple.In the United States, the name seems to have been derived from a couple who were freed from slavery in Lancaster County, Virginia, in 1690. The slaves were identified only as Black Dick and Chriss in the will of John Carter, Jr., a wealthy and influential figure in early Virginia history, and they were to be set free along with three children.After being freed, Dick was found on the Lancaster County tithables lists for the next several years as Black Dick, Free Dick and Free Richard. In 1704, 14 years after he was freed, he was identified as Richard Yoconohawcon. The name Yoconohawcon, with various spellings, was found in Lancaster County records until 1727, even as some family members began to use the name Nickon or Nicken.Information collected by my distant cousin reveals that my tenth-great-grandmother was very light-skinned (perhaps owing to being Native American) and her children (including my ninth-great-grandfather and his descendants) were so light-skinned that they were described as “mulatto” or “white.”That last racial designation explains how no one in the family knew that we had enslaved ancestors. Exacerbating the ignorance was the fact that by the time of the Civil War and slavery’s ascendance as an issue of national notoriety, the Nickens had lived as free men for over 170 years.

I am a man who descends from people who owned other people—and from people who were owned by other people.

I Can’t Change My Past, but It Informs My Life

Remarkably, the notorious document which allowed a human being as an inheritance was probated in the same year that two members of my family, through another line, were being granted their liberty in another man’s last will and testament. The moral polarity is enough to give me psychological whiplash.Scientifically speaking, I guess my sister is right: a three percent portion of someone’s genetic code is statistically insignificant. What isn’t insignificant is that I am a man who descends from people who owned other people—and from people who were owned by other people. Some of my ancestors had the key to their chains passed down to a child in a will, while some had those chains permanently removed in a similar manner.So, what difference does this discovery make? Does it change how I identify racially? No. But it does make me realize that I am the product of people who were treated as God’s own chosen rulers and other people who weren’t even treated as humans. I can’t change any of that, but I can change how I treat people whose principles and perceptions I don’t understand, realizing that all of us have strange, shameful and significant stories written in the books of our family histories.