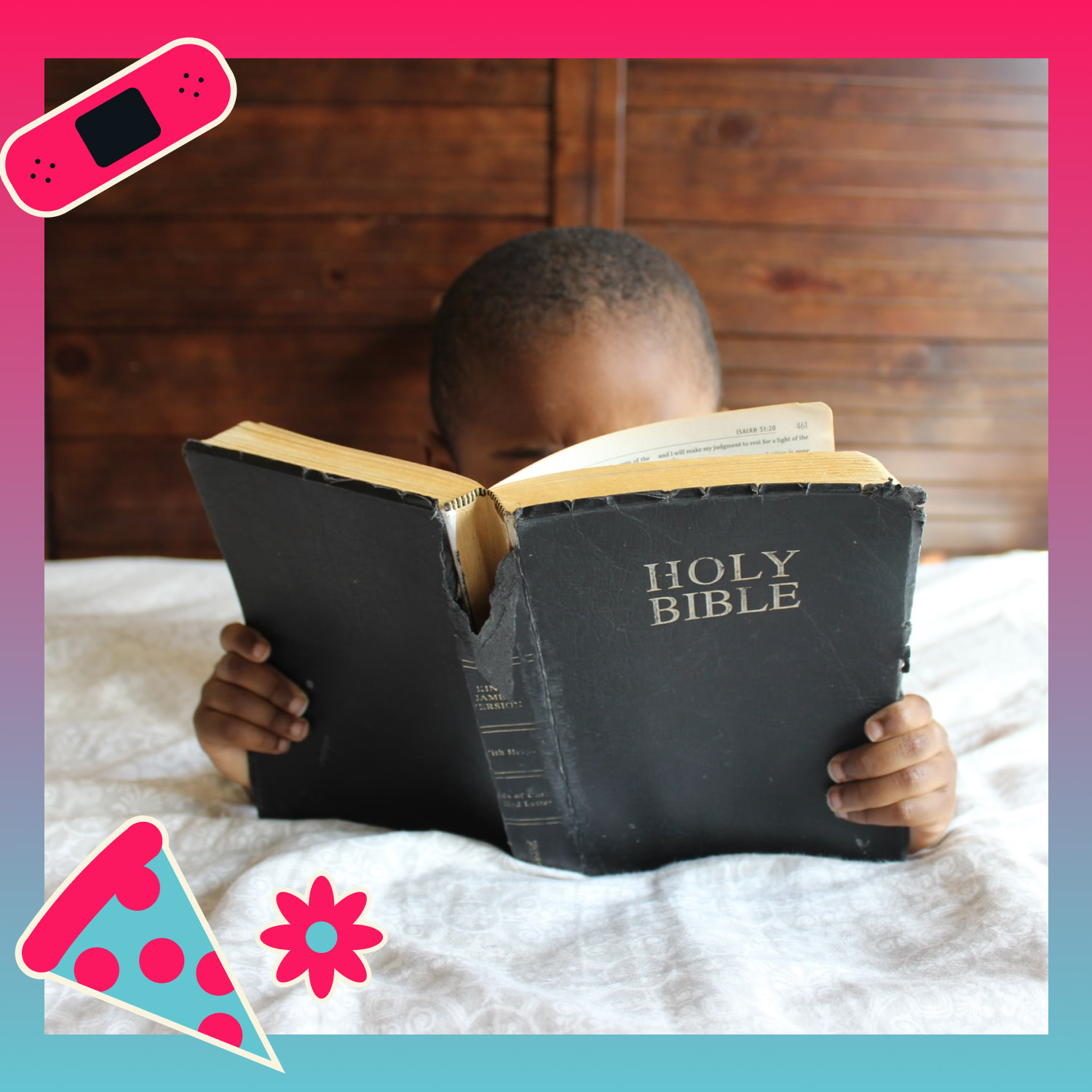

My Conservative Christian Homeschooling Ruined Nostalgia|A Christian mother homeschooling her child.|In Christian homeschooling, the word of God is the most important thing to learn.|While some homeschooled Christian kids rebel, others double-down on religion.

My Conservative Christian Homeschooling Ruined Nostalgia|A Christian mother homeschooling her child.|In Christian homeschooling, the word of God is the most important thing to learn.|While some homeschooled Christian kids rebel, others double-down on religion.

My Conservative Christian Homeschooling Ruined Nostalgia

I don’t remember exactly when I started burying memories of my childhood, but it was around the same time I moved halfway across the country from the sparsely populated and deeply conservative Western state where I was raised.I do remember when I began realizing that looking back on my childhood was painful. It was around 2015, when the internet became obsessed with nostalgia, and every social media platform was inundated with “only ’90s kids remember this” memes. Nostalgia is a tricky thing. It promises comfort—a brief return to the beauty and simplicity of youth before you were corrupted by the realities of adulthood. But in order to be tempted by nostalgia, you have to have something beautiful to look back on, and revisiting my childhood means opening a thousand doors I purposefully closed a long time ago. Memories from my childhood, even the good ones, are like threads sticking out of a sweater. I know pulling on one will be disastrous, unraveling a past that I have no interest in revisiting. I have purposefully built a new life for myself in a different city, surrounded by a community of people who helped me create a life as an adult that looks nothing like my adolescence.

To be tempted by nostalgia, you have to have something beautiful to look back on.

My Family Was the Perfect Target for the Christian Homeschool Movement

I grew up in a deeply religious, working-class family in a small city in a mostly rural state—the kind of place people stop at on their way to a national park. My family bobbed at the surface of the poverty line my whole childhood. Some years we treaded water, and other years we drowned.My dad worked long days at tough jobs, coming home with rough hands and tired eyes, but we still had endless family conversations about budgets and making food stretch until the next payday. The constant stress of living in financial limbo as a child, worrying about losing your home or not having enough to eat, is a fear that lingers well into adulthood. Poverty is its own trauma. I was aware of the cruel and callous nature of the American economic system before I had the language to describe it. My siblings and I weren’t protected from the reality of our financial situation. We began contributing to the family financially as soon as we were old enough. Because we were homeschooled, this involved spending time every afternoon helping with a home-run business, starting in our tweens.

For My Parents, Evangelical Homeschooling Was a Way of Instilling Christian Beliefs

My parents decided against public schooling smack in the middle of a homeschooling boom among evangelicals in America. Whether or not my parents were even aware that they were participating in this trend at the time, I don’t know, but their goals were the same. They wanted to educate us in a vacuum, sheltered from the evil influences they saw around every corner in the secular world, with the goal of creating godly men and women who would bring honor and glory to God. Everything from sex to drugs to liberal ideology was a threat to our souls in the most literal sense, and my mother especially became paranoid about their potential effect on us. She saw demons around every corner. The devil was hiding in the details: the music we listened to, the movies we watched, our conversations with friends. She would spend hours scrolling through our family computer’s search history, writing down websites we visited or the names of songs we listened to, trying to root out the evil that she felt was seeping into our adolescent lives. We didn’t have the ability to set boundaries with her, and she regularly reminded us by going through our phones or ransacking our rooms without our knowledge. When she did find evidence of wrongdoing—a text about a boy, a forbidden CD—she would seem almost triumphant, as if the find proved that her constant vigilance was not in vain.

Homeschooling Was Simply Not a Productive Learning Environment

Our conservative Christian homeschool curriculum varied year by year. We had “science” books that said the earth was 6,000 years old and watched docudramas for history class. We all fell grades behind in math. After I had fallen so far behind it couldn’t be ignored, our dad would come home from his long workdays to spend hours trying to explain complex algebraic formulas to me until I was frustrated to the point of tears. We tried “unstructured learning” for a while, which in function meant we learned little and studied almost nothing. My older siblings begged our parents to let them go to public school, but they were told public schools didn’t offer a quality education.As we aged into our teen years, it became clear that we were on our own. The majority of our education was self-taught. Knowledge was a resource we were starving for, and because we were so far behind, we were desperate to learn any way we could. My siblings’ reaction to our parents’ overbearing strictness was absolute rebellion. After all, if they were going to be punished for the most minor of infractions, why not really push the boundaries? They snuck out late at night to meet up with friends, drank when my parents were away for the weekend and smoked weed in the park after dark. They were often caught, of course, which resulted in a total upheaval. Whenever a wrongdoing was discovered, the house would be filled with yelling and slamming doors. There was crying, there was screaming, there was literal wailing and gnashing of teeth.

It Really Took a Toll on My Mental Health and Well-Being

For my part, I became a straight-laced do-gooder with an anxiety disorder. I went to youth group weekly, two separate Bible studies and church. I never touched alcohol, I never lied to my parents about where I was or what I was doing—and I was a complete mental wreck. I struggled with depression and was constantly afraid of stepping out of line. I carefully followed my parents’ rules, but in my heart, I began questioning the church’s oppressive theology, and I couldn’t shake it. In my late teens, I discovered something about myself that made my relationship with religion even more fragile: I was queer. Looking back now, it was obvious and had been for years, but at the time, it was a terrifying discovery. What was I supposed to do with the knowledge that one more thing about me didn’t fit into the world I was brought up in? It would take me years to tell anyone and the better part of a decade for me to be open about it with most of my friends. It took until my early 20s for me to leave the church, but the day I made the choice, a weight was lifted off me. I no longer had to contort myself into the mold of the Christian woman I was told I had to be. I didn’t have to wage an internal battle between what the church believed and what I knew was right. I was free.

These cultural points, which were so meaningful to others, held no sentimentality to me.

Nostalgia Is Painful for Me, but I’ve Come to Terms With It

Now that I’m older, I’m able to see that my parents were motivated by an all-encompassing fear of the world. I truly believe that although their actions did damage, they knew no other way, and their intentions were good, however misguided. I wonder how much of my trauma was caused by trauma they were never absolved from. Still, a part of me mourns for the lost childhood I could have had. I wish I had been allowed to be carefree in the way so many of my peers were. I don’t relate to many of my friends’ formative adolescent experiences: first romances, school dances, field trips.For a long time, I struggled to understand the pop culture references that came up in everyday conversation at work or parties, and it became my mission to consume as much as I could to make up for it. If someone made a reference I couldn’t parse out, I would immediately find out as much as I could about the subject online. I watched every season of Friends, I binged RuPaul’s Drag Race, my Spotify filled with ’90s grunge and early-’00s R&B. I fell in love with horror movies, which had been strictly off-limits in my youth. In my early 20s, “You don’t seem like you were homeschooled,” became a common refrain from people who would find out about my background. It felt like a small reward for my anthropological efforts. “I try not to,” I would reply. But these cultural points, which were so meaningful to others, held no sentimentality to me. The usual markers of American youth are foreign concepts to me, experienced only vicariously and in hindsight. I’m jealous of my friends’ rose-colored retellings of their own pasts and their capacity to long for that period of their lives instead of trying to ward off memories. The things that do remind me of my childhood—the car radio that was permanently set to a Christian station, yellow-tinted Sunday school rooms with walls covered in Noah’s Ark characters, the empty lot where my family’s first trailer sat—are like the first layer on a bandage over a still-healing wound. I could try to peel it back, but I know what’s underneath.I wish that looking back on my life was appealing instead of painful. Many people in my generation find nostalgia bewitching, but it holds no such allure for me. But there is a bright spot: I love the life I’ve created for myself, and I know my best years are ahead of me.