Cassava Life: Guzzling the Saliva-Fermented Drink of the Amazon|Masato is a fermented drink from the Amazon region in South America.

Cassava Life: Guzzling the Saliva-Fermented Drink of the Amazon|Masato is a fermented drink from the Amazon region in South America.

Cassava Life: Guzzling the Saliva-Fermented Drink of the Amazon

I finally arrive in the humid tropics of Iquitos, the Peruvian port city where Maria, my family friend of 10-plus years, is awaiting my return after a year away. Immediately, I smell something, and after all these years of visiting, I know it well. Masato is fermenting in 50-gallon plastic drums as a work party is being organized for the next morning.“Oye hermano, has vista lo que hemos hecho?”Maria excitedly guides me over to the drums, showing me the off-white, creamy blend of cassava, water and a young girl's saliva. What? Yes. I’ll explain. In fact, I remember distinctly expressing the whole process of this unique drink to a beer-brewing professional on a patio in South Florida after the wedding of a mutual friend. In utter fascination, I listened on as he explained his theory as to why the recipe called for saliva. He expressed that in beer brewing, amylase—a particular enzyme—was used to facilitate the fermentation process. He then explained that it was naturally occurring in human mouths, with higher concentrations in women’s mouths.Well, hot damn.

In utter fascination, I listened on as he explained his theory as to why the recipe called for saliva.

I Had Been Making Masato Without the Key Ingredient

Maria’s son, Jefferson, wakes up early to dig up some cassava root. I follow him through the field, not minding the morning dew soaking my clothes as we walk briskly through the low-lying jungle fog. A freshly dug plant has several roots cut away, peeled, chopped and set to boil. I remember the cooking process taking about an hour. Then, after the roots are soft, the pot is pulled off the fire to cool. Jefferson lays out the now-cooled roots into a dug-out log, sort of like a canoe, and begins to pound them with a blunt staff made from a beautiful red hardwood called palo sangre. DUUM DUUM. The thuds are rhythmic and blend with the bird songs above. I ask for a turn and start to pound the soft roots into a creamy slurry. As I'm working, the sticky goop begins to take shape, and Jefferson's sister and cousins begin to take their positions nearby."Why do you all ferment the cassava roots?" I ask Jefferson between thuds.He looks at me with a strange countenance, the kind you receive after asking about something so strange and foreign to me and so commonplace to him. "We ferment the roots so they can last," he says. "The masa can be kept for weeks and then have water added to it whenever we want so we can drink. It also changes the flavor and texture a lot. It's just always what we have done with this plant. You don't ferment cassava in your country?" I love the question."Jefferson, I am the only person I know, as of now, who ferments cassava where I live," I reply. "I'd like to document the process of what you all do so I can share with my friends and people who also grow this fantastic plant. It's a real treasure what you all know here.""And who spits in your yuca for you!?" he asks curiously while holding back laughter."I do! I don't have daughters, and I'm definitely not asking anyone else to do this!" Jefferson erupts in laughter. "Only the women are supposed to chew and spit the roots back in!" I laugh with him and at the fact that this is what it looks like to attempt to emulate a practice without its place. It takes a village, indeed.

Now the chewing and spitting ensue.

Making Masato Means Taking Part in a Family Ritual

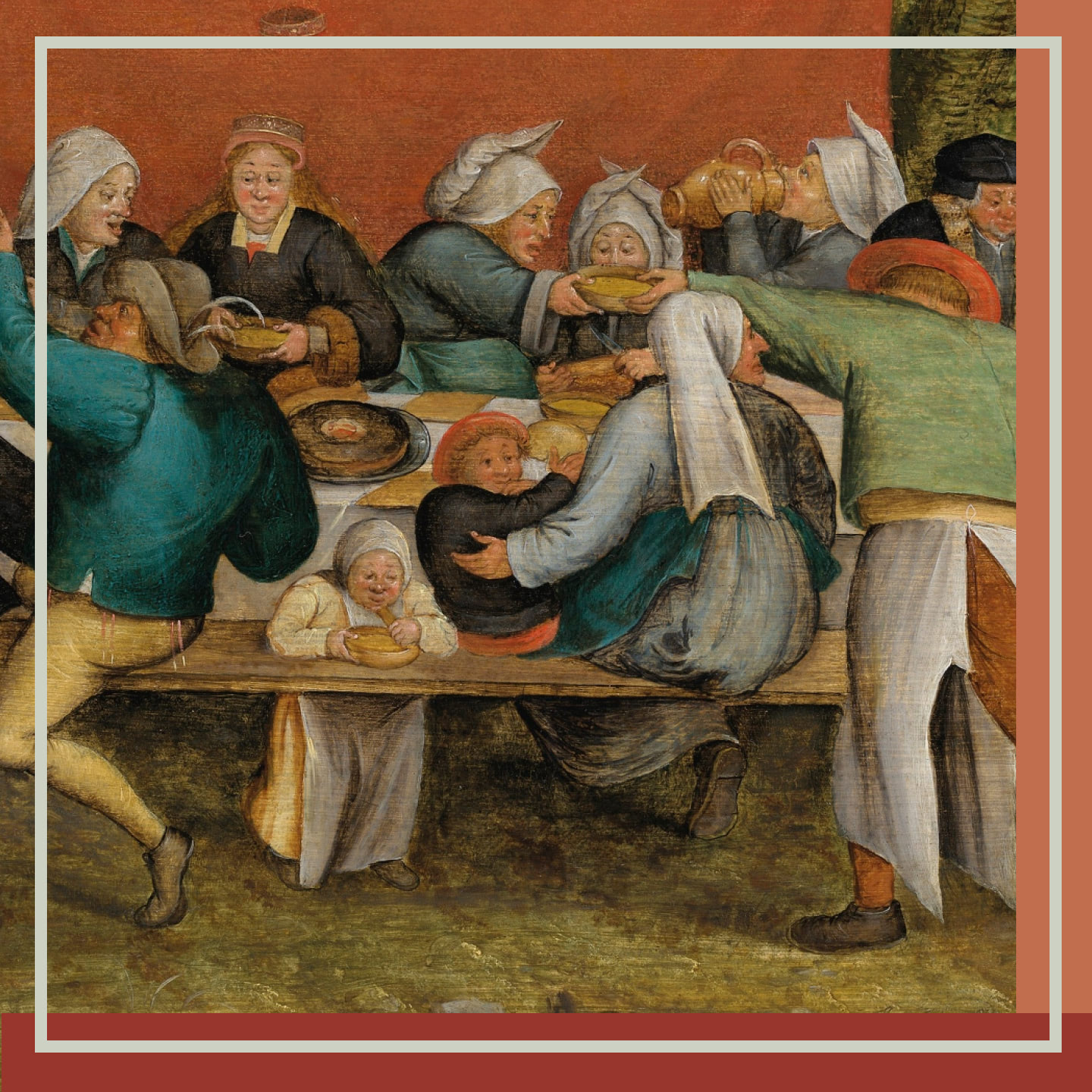

The cassava roots are an unrecognizable mess at this point, and the hard work is over. Now the chewing and spitting ensue. The girls are happy to partake in the family ritual and begin taking spoonfuls of the mash and chewing it thoroughly and, after 30 seconds or so, spitting it back into the dug-out canoe. I'm taking photos and thinking back to stories I was told about the importance of partaking in the consumption of this masato beverage. To decline is to put yourself outside of the circle, to embody the opposite of communal care, at least in their eyes. To engage and accept is to say yes to life itself, as the microbes present in this fermented beverage are very much alive in every way. The mass of yuca only had about 20 chewed up and spit out spoonfuls, maybe two percent of the total, but it's just enough to jumpstart the fermentation process.Thinking back to the brewer's words about amylase, I start to imagine the enzyme helping to break down the starch. Jefferson brings over some towels, and at this point, the vat is covered—limiting flies and critters from entering—and is allowed to ferment. In this souring process, I remember Maria telling me that the nutrition of the cassava is improved upon and helps their people stay healthy."Sort of how we take probiotics," I tell Jefferson. "Sort of how our European family eats sauerkraut. The culinary traditions of fermentation span the world."

I Hope to Bring Home the Memories of This Drink’s Power

Two days later, a massive bowl twice the size of a normal breakfast cereal serving gets handed to me in the morning. Maria has a huge smile on her face as I lift the bowl to my mouth and begin eating my liquid meal. It's sour, thick and a touch sweet from some additional sugar which the elders normally frown upon. A few minutes later, I am through the bowl and pass it full to Maria's husband, Gabriel. The slight buzz is undeniable. He thanks me for the pass and has that look on his face saying, "Yeah, you're back, aren't you?""Traditionally," Gabriel shares, "the people gather for shared work, like clearing land for a small farm or help to build a neighbor’s house. They call this the minga, and it's without a doubt that masato will be present in several five-gallon buckets to support the process. It keeps us full and lets us be joyful while we work."I recall following his cousin Isaias as he, seemingly without effort, carried a drum with several hundred pounds worth of masato in it across uneven earth and slippery clay spots exposed by a recent rain. We were en route to clear land with a machete and chainsaw in order to plant more bananas, cassava and corn. There was a certain flow to the day, working in phases of strong energy and then taking collective breaks and being served masato as we rested in the shade of the cetico trees overhead. A machete in my hand, I consider the communal tool that is this fermented root drink. It gathers the people together under a shared cause and allows for tradition to live on in a daily way. The daydream is broken by Gabriel's quick steps toward the farm to cut some racks of plantains for the day's lunch."The ancestral food ways that still exist in the world are critical to our understanding of how to be in best relationship to nature," Gabriel says. "We are here to steward these technologies and make sure they are preserved for generations to come—and to share them with those who come from so far away to learn them, like you, brother."Gabriel's words rested deeply in me, and I carry them to this day. I'm reminded of them when I walk through my cassava plantings here in Florida, giving gratitude for such amazing beings that grow so readily. The wind blows through the palmate-like leaves of cassava plants overhead, almost beckoning me to visit my friends again—and share some masato.Soon enough.