The Doe’s Latest Stories

I’ll Never Forget My Time at a Manhattan Women’s College

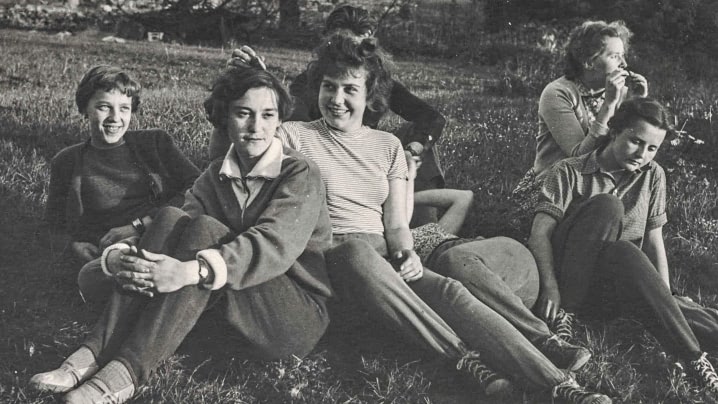

In 1964, I graduated from high school. Like many teenagers, I was faced with the puzzling question of what to do with the rest of my life. Although I was popular in school and had been president of my senior class, I was actually a remarkably poor student and hated anything related to the classroom. An academic career was most definitely not in the cards for me. I had four older brothers, but none of them had ever left home for their higher education. For my parents, sending them away to study was unthinkable. The boys remained in the Midwest where they were born and raised. But when I came along, the first girl in a large Catholic clan, my parents were faced with a dilemma. Besides being a poor student, I was also an immature flower, lacking in any self-discipline and filled with an untamable sexual curiosity. It was decided that I should be enrolled in an exclusive women-only college in Manhattan (back in the day known as a finishing school) run by the same nuns that had tried to educate me from the beginning. I had never been away from home, not even to summer camp, so the prospect of this move to the East Coast presented a monumental leap forward. I was both thrilled and terrified. Looking back, I realize that there were numerous considerations for getting me into some sort of educational environment with adequate supervision. I can’t help but sympathize with my parents. What else could they do? I had grown up in the privileged suburban community of Grosse Pointe, Michigan. My father was a hard-working M.D. in private practice. He was financially well off but by no means affluent. My classmates and friends, by contrast, were mostly from superrich families with fortunes that had passed down through generations. Growing up, our playgrounds were the sailing, golf and tennis clubs where our parents were members. Eventually, most of my childhood friends became debutantes and were introduced into polite society at balls or tea dances. As expected, they married well, created lovely designer homes and produced the two children that society expected of them. Leaving town at 17 saved me from this predictable fate. I will be forever grateful.

Leaving town at 17 saved me from this predictable fate. I will be forever grateful.

My Mother and I Visited New York and Fell in Love

All my life I had been sheltered in a private school run by a traditional order of French nuns. The Society of the Sacred Heart was established in Paris to educate daughters of wealthy and privileged families. There was no thought of a career in my future. In the late ’60s in the Midwest, feminism was just a distant siren’s song calling from a faraway time in the future. Since I was not cut out for university studies, it made sense that the next step on my agenda was to do some serious husband-hunting and for that, my cultural boundaries needed to be expanded. What better place than New York City? One of my childhood friends was an heiress to the Scripps publishing fortune. Anne and I had played together as schoolgirls, and she was now attending a distinguished finishing school in Manhattan. She had an elegant and sophisticated grandmother that I had always adored. Over the years, she had encouraged my friendship with Anne, entertaining us with wonderful events that were far beyond the scope of my more modest home life. To keep our girlhood friendship afloat, Grandma Ruth suggested that I join Anne in New York. She wrote a glowing letter of recommendation to Reverend Mother on my behalf and sure enough, I was invited to New York for an introductory interview. My mother booked a flight to New York and reserved a room at the Plaza Hotel. I had never been out of Michigan, so this first visit to the exotic city on the Hudson River was thrilling in the extreme. One of my fondest memories is from our first evening away from home, just the two of us, in the palatial grandeur of the fine old Plaza. Toward evening, my mother reserved a table for two in the hotel bar. We sat ringside listening to a handsome Broadway heartthrob as he sang love songs from the stage. My mother ordered her usual dry martini and I, dressed up in my best dress and feeling quite mature, sipped an alcohol-free Shirley Temple through a straw. It was sheer heaven!

The School’s Reverend Mother Was a Fun-Loving Woman

The following morning we took a taxi up Fifth Avenue to East 91st Street for my first view of the elegant residence that was to become my home for the next couple of years. This magnificent neoclassical villa had been built in 1908 and, upon the death of the owner, had been gifted to the Sacred Heart Society. Reverend Mother greeted us as we walked through the large double doors that led into the grand entrance hall. She was a round little woman dressed head to toe in the official black habit of a nun. Her head was encased in a fitted white bonnet with a sheer black veil. A small, gleaming, silver crucifix hung on a cord from her neck. Of course, I never saw her dressed any other way. Nuns always looked the same. Only their radiance was allowed to be individual. To my surprise and delight, she turned out to be a jolly, fun-loving woman. Full of energy and enthusiasm, she welcomed us warmly and took us on a tour of the magnificent house. I will never forget my first view of the elegant marble staircase that rose up through the center of the house. I had never seen this kind of grand architecture. The walls were clothed throughout in beautiful complementary shades of green and pink Italian marble. Built in a grand Rococo style, the building expressed the kind of lush excess that seemed perhaps fitting for a budding princess on her way up in the world. The red-carpeted steps of the staircase led from the ground floor all the way to the huge ballroom at the top of the house. I gazed up at the massive skylight at the top surrounded by moldings of flower wreaths and golden cherubs. I was lost in a world of wonder.Regardless of my poor high school grades, I was accepted into the school. Like so many things in life, it’s all about who you know. In early September, I packed a large trunk full of dresses, shoes and matching handbags and flew into a new life in New York City. I would never return to the country club life of suburbia.

I was lost in a world of wonder.

My Time in New York Still Feels Like a Dream

So what did one do in a finishing school in the ’60s? Well, for one thing, we were expected to learn how to play bridge. I skipped the first lesson and to this day I have never really understood how the game is played. I watched all year long, as most of the girls played obsessively at all hours of the day and night. Eventually, a house rule was established forbidding bridge before 7 a.m. Perhaps this is where I first established a lifelong distaste for table games. Another more distinctive memory is of the many sweet boys who showed up for the weekend dances in the grand ballroom at the top of the stairs. Reverend Mother extended her invitation only to boys from Ivy League schools, like Princeton and Yale. The carefully screened young men would travel by chartered bus for a few hours of non-alcoholic small talk, music and innocent flirting. These mixers happened several times a month and had a high priority on our social calendar. We were expected to show up and chat politely with an ever-evolving selection of distinguished young gentlemen. Socializing and ballroom dancing were essential skills that young women were expected to master.Other important activities on the menu were cultural events: classical theater, Broadway plays, concerts and ballet. We were fortunate to take part in all the great things that New York had to offer in those days, but I think most of us took it for granted and didn’t realize what a gift this was. We also had weekly French lessons and a visit now and then from Miss Freemantle, a professor from NYU, who tried to instill an interest in us in Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust. Not much luck with that part of the program.After graduation I stayed on in the city, working for several years at one poorly paid job after another. Through sheer youthful persistence, I survived the slings and arrows of daily life in the city and with time, evolved into a stylish, sophisticated New Yorker. Eventually, I landed a cool job with a Madison Avenue ad agency. My boss was a handsome Swiss man and together we moved to Europe, made a life and I never returned. I lost touch with my friend Anne. She died in 1994, and I read the details of her murder in The New York Times. In a jealous rage, her husband smashed in her skull with a claw hammer before committing suicide by leaping from the Tappan Zee Bridge near their home in Brownsville. She was 47 years old. I was glad that Grandma Ruth, the much-loved dowager queen of my youth, had died peacefully several years before and was spared the sordid details plastered all over the newspapers.And yet, my journey from Grosse Pointe to finishing school in Manhattan lives on in my memory as a nostalgic dream that has never lost its luster.

I Flew to South Africa and Quickly Became a Teenage Meth Addict

On the day of my eighteenth birthday, I took the money I had earned as a child actor in Mexico—almost $25,000 that my parents could no longer legally keep from me anymore—and bought a plane ticket from Switzerland to South Africa. There was no plan, other than to just get down there and figure it out. With 25 grand in the bank and no responsibilities to speak of, you really don't need a plan. Leaving my friend's house—that I had been bumming around in since my girlfriend and I broke up months earlier—I got on the plane in Zurich with my laptop and the phone numbers of a few high school friends from South Africa. Off I went on one of the most ridiculous adventures of my life. Aside from getting addicted to crystal meth, I would take massive amounts of hallucinogens, smoke crack for the first time, become good friends with a professional car thief and his family, go on road trips across Southern Africa and befriend street kids in some of the roughest slums on the world's roughest continent.

South Africa and Its Slums Were a Culture Shock

Growing up in Latin America, I was accustomed to seeing real poverty—not the kind that Americans think of, where so many obese “poor” people have iPhones, fancy rims, fat government checks and a perpetual chip on their shoulder. In Africa, even in the richest nation on the continent, they have real poverty. It was astounding. What I saw in the slums of Cape Town, Johannesburg and other major cities in the region would be inconceivable to most Americans.My journey into crystal meth addiction began not long after I arrived in Cape Town, where my first task after finding an apartment was to buy a car. My original plan was to buy a four-by-four truck and try to drive across the continent to Cairo, but I quickly realized my $25,000 wasn't going to cover it. In fact, cars were not much cheaper in South Africa than they are in the West. Instead, I bought an old Audi sedan made the same year I was born that had a smashed headlight from a previous wreck. It was a great car but needed some spare parts to be in decent shape. While searching for them, I ended up getting in touch with a guy from Mitchells Plain—a rough, largely Islamic area outside Cape Town—who supposedly could get any parts I needed for cheap. Meeting him would be a defining moment of my time in Southern Africa. Let's call him Abdul. Abdul was a native-born South African of Pakistani heritage who, while technically a Muslim, did not really follow his religion in a serious way. In fact, Abdul, who ended up becoming a good friend, was a crackhead and a professional car thief, who specialized in repainting stolen vehicles, throwing new serial numbers on them, getting new papers and shipping them to Botswana to sell. His wife was a crackhead too and super sweet.

With 25 grand in the bank and no responsibilities to speak of, you really don't need a plan.

It Wasn't Difficult to Get Me to Walk on the Wild Side

Abdul got me the Audi parts I needed, but he always found a way to make sure that I had to come back for something else. I soon realized this was because he wanted me to bring him money so he could buy crack for him and his wife. No doubt Abdul thought he was using this silly American kid with too much money. But we gradually grew closer and closer, to the point that he would sit on the toilet with his pants down, pooping, and tell me to come in to hit a joint with him.One of the many times he asked me to borrow money, he offered to let me hold onto his 9mm pistol as collateral. I had no idea whether it was legal or not, and it made me uncomfortable just being next to it, so I lent him the cash without keeping the weapon. I can't remember if I ever got it back. Abdul and I would often go down to the crack house together. He would get crack, and I would get whatever else they had: pot, barbiturates, ketamine, amphetamines, coke or even crystal meth. One time we pulled up and there was a cop standing outside. “We can't go in there,” I told Abdul, glaring at him. “What's wrong with you!?”Abdul looked amused. “Oh, don't worry man,” he told me in his adorable South African accent. “That's my brother. They just pay him a bit to protect the place.” His brother was actually really cool and a lot more responsible than Abdul. The first time I freebased methamphetamine was with a beautiful blonde South African girl of British heritage—let's call her Claire—who was a friend of a friend I knew from Switzerland. For 24 hours we stayed up in my beachfront apartment: talking, drawing, writing, philosophizing, touching each other, smoking pot. It was amazing—or so I thought. Then came the comedown, which is one of the most miserable experiences a person can have. It's torture, and it makes you willing to do just about anything to get more. I knew meth was bad news, but man was it fun to chat with Claire all night. It's like your brain goes a thousand miles per hour and everything is just perfect. Once I realized I could get the stuff from Abdul's crack house, they became my regular supplier. At the time, I was paying about 10 South African rand ($1 U.S.) for a gram. When I left for Europe and then the United States, I realized how absurdly cheap that was. In Miami, the going rate was around $60 per gram. In France, I couldn’t even find it. Thankfully, the outrageous prices and my lack of money eventually forced me to quit.

Would I do it again? I don't know, actually.

I Bottomed Out and Figured Out Who I Am

For pretty much the rest of my time in South Africa—about six months from the time I started freebasing meth out of broken light bulbs to the point where my bank account got so low I couldn’t afford to renew my visa—was spent on meth and/or various other drugs. It was party after party, nonstop. Abdul had an “employee” named Peter. While Peter was technically free to leave any time, the relationship almost struck me as one between a master and a slave. Peter, a Xhosa speaker (like Mandela), slept out in the garage in a tiny little room no bigger than a broom closet, with literally nothing but a small piece of foam and some trash on the floor. Abdul would bark orders at him to go buy a cigarette (yes, one cigarette), get him a car part, grab tools or whatever. Peter was a sweet kid, and I felt bad for him, but living in Abdul's closet with a piece of foam to lay on was better than the deplorable conditions that millions of South Africans lived in—some just on the other side of the bridge, less than half a mile from Abdul's little house. The cops in South Africa—where an average of 58 people are killed per day, putting in the top ten for murder rate in the world—were beyond corrupt. But I was used to the rampant police corruption from my days in Mexico, Brazil and other poor nations. I had quite a few experiences with the South African cops, and most were pretty pleasant, actually, because they realized I was American. One interaction, in particular, has stuck with me throughout the years, even though I was plastered when it happened. It's hard to remember how many tequila shots I had at the bar that night with some friends, but it was a shitload. After making it about halfway home, I crashed my car into a roundabout. “Oh crap,” was my first thought. “I'm screwed.” The front bumper was a total mess, and the rim for one of the wheels was destroyed. But it seemed like the car was still running. Yes! Fortunately, the super-helpful police showed up and asked me what was going on. I offered them the equivalent of about $100 if they would help me get home and get my busted car back on the road. They literally helped me change the tire and waved me goodbye. We never discussed the fact that I was hammered. By the grace of God, I made it home without killing myself or somebody else that night. So what's the moral of the story? I don't know that there really is one. As a Christian today, I look back at those days in horror. And yet I recognize that it was that time that led to me being transformed, and eventually helped make me who I am today. Would I do it again? I don't know, actually. There is one conclusion I can make for sure: God was looking out for me or I wouldn't be here today.

My Passion for Scuba Diving Has an Environmental Cost

I discovered scuba diving in my early teens, at an age when I was desperately looking for something to connect to. I like to say I grew up with seawater in my veins, with a dad who was a scuba diver in the coastal city of Karachi. I loved being out on the sea, so when I was finally old enough to get my diving certification I jumped at the chance. To be part of a world I had loved for so long—and have something that was so uniquely mine, because no one else my age even knew about it—made me feel special, and in a weird way not quite so lonely anymore. As excited as I was, I could never have predicted the way my first dive felt. It was surreal to suddenly become a part of a completely different world. The way I was so aware of each breath rushing through my equipment, the flow of bubbles each time I exhaled. How closely I saw a tiny stingray emerge from being hidden in the sand just as I was floating above, or how weightless I felt the entire time. Scuba diving offered me an escape like no other. It was a freedom from responsibilities and stresses because when I was diving I was no longer part of my everyday life. Life above the waves was forgotten for that hour. The world only came rushing back when I reemerged. A big part of my connection with scuba diving and the ocean has always been the way it’s healed me. At a time when I barely understood my own mental health and what I was dealing with, scuba diving became a respite for my anxiety. It allowed me to escape from my own thoughts and feel my mind calm down where otherwise it would be racing with thoughts I felt I could never control. The weightlessness would take over and I would lose myself in the colors of the stunning corals and the fish swimming past me as if I simply wasn’t there at all. I think I’ve always felt so pressured to act perfectly because it seems like someone is always watching me. To feel unseen, to be completely silent, was something I had never felt before—and I welcomed it greatly.

Suddenly, dives no longer felt the same.

Diving the Great Barrier Reef Was a Dream Come True—and a Wake-up Call

For my first few dives, I was so lost in the wonders around me that I didn’t think of anything but myself. Then I got a chance to dive at the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. It's a spot on any diver’s bucket list, and I couldn’t have been more excited to dive there. When we entered the water that day, life under the sea took on a whole new meaning. The beauty back home that I was obsessed with paled in comparison to these otherworldly colors. I remember being so excited because I got to see clownfish; marine life I had never even known of before surrounded me. Corals rose up in entire forests above and below. But right from the start, I struggled to adjust to the water. Where my previous dives felt almost effortless, this one didn’t fit right. My sinus issues acted up, meaning that I couldn’t equalize properly. Going deeper into the water made me more uncomfortable, so I kept having to increase and decrease my depth trying to find a comfortable space. During that time I noticed my fin nudge against a coral reef formation, causing a small piece to fall off. Looking back, I now realize that moment changed the way I thought about diving. As we came back up to the surface, my mother told me she’d been in Australia 20 years before, and had the opportunity to dive at the Great Barrier Reef back then as well. What she had come back to was nowhere near the same. The reef had lost most of its color, and the biodiversity and marine life my mother remembered in awe were nonexistent. Suddenly, dives no longer felt the same. I was now a lot more aware of what I was doing to this world I was intruding on. I saw divers who accompanied me spearfishing, the whoosh of the spear in the calm waters, the blood and then the lifeless fish stringing along on a line as divers continued their journey in the water. I—the intruder—was calmly swimming around while the fish whose homes we were exploring floated lifeless just a few feet away. I started thinking about my presence in the water, and what the continued impact of human interaction had meant for the oceans we explored. The Great Barrier Reef is a well-known tourist attraction so its decline has been noted, but what about the waters I had grown up on along with the countless other coral reef ecosystems and marine habitats whose destruction no one seemed to care very much about?

I’m not sure what this means for my diving future.

Good Intentions Don't Keep Us From Causing Harm

Over the past few years, I’ve become far more focused on being environmentally conscious and making an effort to learn about living sustainably. But when it comes to my diving experience, I seem to be drawing a blank. There’s barely anyone around me who’s really looked into what diving sustainably could mean. Even the community that wants to do more is held back by mounds of red tape and legislative confusion about who is allowed to take action. I’m not sure what this means for my diving future. I know that my impact on the marine life around me during the dive goes beyond accidentally breaking off a piece of coral reef. My very presence can cause harm in ways that are still far beyond my limited understanding of the environment. But I want to learn, and I want to make sure that my love for the ocean that has supported me through some of my worst times can extend into a love that takes care of it in return. The realization that our love can be damaging has been a wake-up call to the crisis we are putting our environment in, because even when we do something with good intentions our ignorance can mean we do more harm than good. Realizing my love was hurting what I loved became the reason for my journey into being more sustainable and environmentally conscious. I’m hoping that journey can help me find the answers I’m still looking for.

I Don't Know You, Let's Live Together: Traveling With a Stranger During the Pandemic

Here’s a general breakdown of how a normal dating progression tends to go: First date, drinks. Second date, dinner. Third date, drinks and dinner. Fourth date: dinner, drinks and an activity. And here is the dating breakdown of my most recent relationship: first date, drinks and more drinks. Second date, dinner. Third date, drinks and dinner. Fourth date—drinks, then casually spending 94 days in a row together, driving across the entire Eastern seaboard of America with two dogs and all of our stuff, as we attempted to navigate and survive a once-in-lifetime global pandemic.When COVID-19 started making its way across the United States in March of 2020, there were several articles about couples who just met quarantining together and some even deciding to live together. My favorite headline came from Glamour: “Are Couples Who Moved in Together for Quarantine Okay?”Many of those couples did it because of ease, some out of necessity, and some out of complete and utter boredom. It was both the most romantic and unromantic approach to dating, much in the vein of, “I want to spend every single minute with you—mostly because you are a body that just so happens to be here.”But if you were to ask me why I spent 94 straight days with basically a total stranger, my answer would be pretty simple: It just made sense. We never planned anything more than a week or two out, and like the rest of America and the world, we were forced to make every major life decision, slowly, day-by-day with equal parts confusion, uncertainty, fear and cautious excitement.

She was just fresh off a divorce and I was fresh off a haircut.

How It All Started

I met Emily at the end of February 2020 on the dating app Hinge. It’s like Raya but for poor people. Our first date was an epic bar crawl through the Gowanus-Park Slope area of Brooklyn. We had good chemistry and a fun, bombastic rapport. She was just fresh off a divorce and I was fresh off a haircut. I would describe my previous dating history as a colorful contradiction of being a lifelong serial monogamist with commitment issues—kind of like a guy who joins the Army but hates war. I later found out that I was Emily’s first online date after her divorce so, in a lot of ways, we were an ideal match because we both longed for connection. Our night ended the same way all first dates in Brooklyn end: having whisper sex in a cramped, tiny apartment so you don’t wake the neighbors who can hear everything through the adjacent paper-thin walls. While your dog watches. We then had a second date a few days later where I went to her apartment to watch Jojo Rabbit, which has one of my favorite endings of any movie ever. Once the credits started rolling, the film shows this passage:

- Let everything happen to you

- Beauty and terror

- Just keep going

- No feeling is final.

- - Rainer Maria Rilke

My Little European Jaunt During the COVID-19 Pandemic

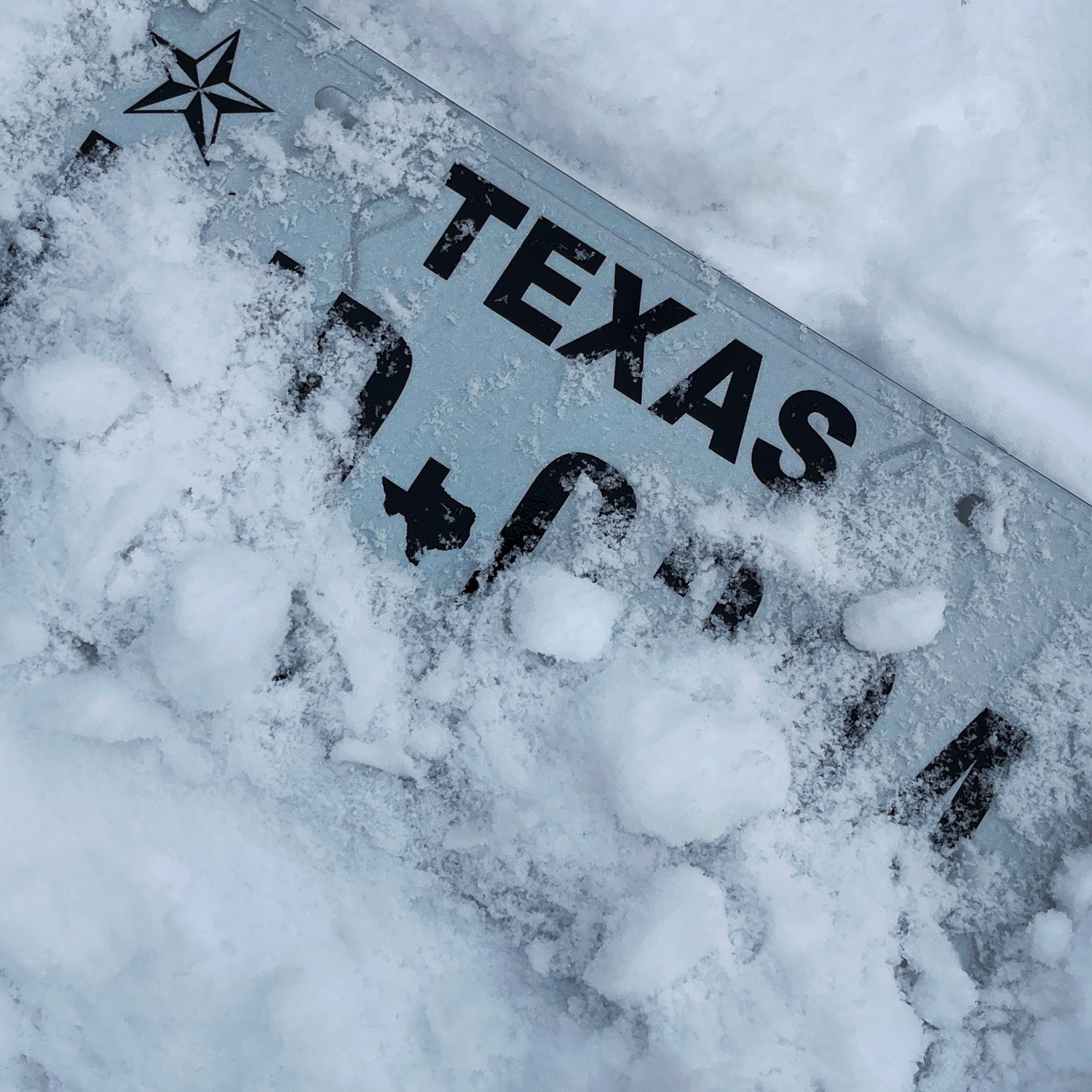

I apprehensively decided to go through with my long-planned vacation to Vienna, Austria, where I was basically crashing my best friend’s honeymoon. Like they say, “If you can’t beat them, be a third wheel and pretend you just got married.” Our trip was fantastic and eerie, with the ubiquitous news of a looming pandemic buzzing in every bar, museum and cafe. While I was in Vienna, I maintained contact with Emily, and on my very last night in the majestic city, President Trump announced that all travel to and from Europe was suspended. Because Trump made the declaration in the middle of the night, I woke up to a series of hilarious and not so hilarious texts from my friends and family saying things like: “Hey you’re stuck in Europe forever, Emperor Trump has decreed it so.” “Can I have your dog?” “Enjoy Vienna for the rest of your life.” Luckily, my flight was the next morning so I was able to barely slip past the Trump travel ban by a day and make it back to Brooklyn safely. As soon as I landed at JFK, Emily picked me up. On the way home, I casually mentioned to Emily, “Hey I think I’m going to go to my uncle’s house in New Jersey for a week until this blows over. I’m guessing it’ll be for a week or so.” OK, so I was a little off by about 63 weeks.I asked her if she wanted to join me and used the very effective pitch that my uncle’s house happened to be a fantastic, epic and sprawling mansion in the remote woods of suburban New Jersey that was also completely unoccupied at the time. Emily reluctantly agreed to join me with her brutish, yet somehow baby-like pitbull, Taco, under the guise that she had to go back to teach at her Brooklyn high school on a moment’s notice. I am a comedian/actor/podcast host so I could be anywhere other than in my parent’s favor.

Getting to Know Your Quarantine Lover

It was here that the reality of our situation and the pandemic started actually settling in, as we silently gazed at each other in a remote, cavernous mansion in the middle of nowhere. I subconsciously whispered a key thought to myself that I know Emily was also considering, “Oh fuck, I don’t actually know you.” This was hilariously manifested in several ways including going to a pandemic-barren Whole Foods together for the first time and literally uttering these words as we nervously perused the aisles, “So, what kind of food do you eat?” It wasn’t until about a month or so of quarantine together that we even knew each other’s middle names. Our cohabitation was helped massively by the fact that Emily actually brought a get-to-know-you icebreaker card game where we were allowed to ask each other questions about our personal lives. So as the world seemingly crumbled around us, Emily and I pulled out a bottle of my uncle’s finest red and took turns pulling cards that would hopefully give us more clues about the stranger sitting in front of them. It turns out Emily was from Pottstown, a gritty but friendly suburb of Philly. She grew up as a determined, tough and chronic overachiever, and split time between her divorced parents. I was from an idyllic and boring suburb of Chicago, with a childhood riddled with joy, repression and overheated perfectionism, sometimes all at once.

Who the fuck wants to be sober in a pandemic other than Trump?

Booze Helped Ease the Tension

I think It’s important to take a timeout here and give a quick shoutout to alcohol. I was a moderate weekend drinker before the pandemic but during the pandemic, I discovered it was possible to consistently have wine teeth that resembled a boxer who had been punched in the face several times by an angry Russian with mob ties. There’s a reason that liquor stores were deemed “essential.” Alcohol calmed our nerves and allowed us to open up more quickly than if we were sober. And who the fuck wants to be sober in a pandemic other than Trump? We saw how that turned out. It makes you say dumb shit like, “Hey maybe you should drink bleach.”We spent our days in New Jersey working. She taught children and brightened young minds over Zoom, and I dreamt of new and effective ways to tell dick jokes to strangers for approval. At night, she’d cook dinner (I’m not sexist) and we had great wine and watched classic movies like Groundhog Day, Before Sunrise and Before Sunset. Toward the end of our first week together, my cousin and best friend Andrea started texting me, floating the idea of us driving down to Sarasota, Florida where she had a fantastic and most importantly, free house. I knew Emily was apprehensive about coming to New Jersey, so the idea of driving 1,200 miles with two dogs and a loose plan would be a stretch. So I “slow-played” the Florida trip, by casually mentioning it a couple of times. Since our first full week in quarantine went significantly well and without a hitch (other than her pitbull devouring one of my dog’s toys), eventually, and much to my surprise, she agreed.

Heading South

So, we packed up our several bags, two dogs, their beds and squeaky toys, and crammed into a rental car dead set on making it to Florida in less than 24 hours. We cruised through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, D.C., Virginia. The further south we drove, the more the landscape opened up, revealing hundreds of barren miles of highway, sparsely populated rest stops and gas stations, shuttered storefronts and sparkly, flashing neon signs that read, “Stay at home.” One particular rest stop was so deserted that several cars formed a makeshift drag race, sporadically peeling out as their tires burned rubber, scorched our eardrums and gave us the staunch impression that we were no longer under the pretense of “normal times.”Despite the palatable uneasiness of traversing a drastically haunted America, I was exceedingly grateful for leaving New York City, especially as news of the COVID-19 cases and death count continued to mount. Waking up in a Virginia hotel room the next morning, hundreds of miles away from the epicenter of the coronavirus, I couldn’t help but be thankful to be safe in a warm, clean room, with Emily and the two dogs. And it was right around this time that I began to internalize one of the greatest lessons from the pandemic: When time stops, you have no choice but to look at what’s in front of you and be grateful.

She had to go back to teach at her Brooklyn high school on a moment’s notice. I am a comedian so I could be anywhere other than in my parent’s favor.

The Pandemic Gave Me Reason to Reflect

When time and the world stop, as they did during COVID-19, you are gifted with the opportunity of seeing the wheel for what it really is, a man-made construct that can be easily flipped over, torn down and reimagined into something more humane. If pre-pandemic me woke up in that very same hotel room, my first thoughts would be along the lines of: “Email someone to try and get a job,” “Get more followers on Instagram,” “Is that how you look with a shirt off? You look like actual milk.” Instead, I quietly gazed around that Marriott Residence Inn and thought, “Wow, a room.” “Cool, a bed.” “This girl next to me is very sweet.” The beautiful simplicity of these thoughts is nothing to scoff at. We’ve all heard about beer goggles. COVID-19 gave us all the opportunity to have presence goggles, the intense ability to sit with our reality and find something, anything to truly feel and be grateful about.

Florida Was Weird Yet Great

The next morning, we did what we would later term a “full company move,” which meant once again packing up all of our stuff, our dogs and hopping into the car to continue our journey to Florida. Somewhere around Gainesville, we stopped at a gas station and saw a pickup truck full of pit bulls in cages and thought, “Oh this is the batshit Florida everyone talks about.” After hearing two different people with no masks on and very few teeth say, “I don’t care what the government says, they ain’t shutting my vape store down,” we made the sound decision to not stop again. And the even better decision to never vape. We eventually made it to Sarasota, dropped the dogs off and met my cousin on a boat that her boyfriend owned. To go from the COVID-19 hub of New York to the cool ocean waters of Sarasota is like going from a jackhammer to a back massage. The ocean air was a welcomed assault on our senses, as the teal, translucent intercoastal water lightly splashed at our feet, politely informing us that there is actually an easier way to live. And we did live that way. Here is our breakdown of how we lived for the next three months of our quarantine: seven different Airbnbs, five rental cars (changing them so many times that it began to feel like we were in the witness protection program), 120 coffees, one George Floyd rally, 14 trips to Publix, five boat rides, 25 trips to the beach, 30 straight nights of drinking, five dolphin spottings, a month of watching the documentary, The Last Dance, endless nights of card games, connection, laughs, incredible sex (some in a hot tub—sorry Emily’s body), one very negative Airbnb review and an odyssey unlike anything I’ve ever experienced or probably will experience again.

We Couldn’t Escape the Pandemic Completely

But our stay wasn’t without tragedy. Andrea’s dad, my uncle, was admitted to the ICU due to COVID complications. Fortunately, he made it through, but the same couldn’t be said for her mom, Ronda, who passed away in July of 2020. One of the last nights of our time in Florida, I got an urgent text from my sister while I was on a boat in the middle of the coast, saying that my grandma was dying and I had to say goodbye over the phone. This was extremely unsettling for so many reasons, including the fact that I was completely hammered. So Andrea and I stood at the edge of the boat as it was anchored by a nearby island, and we told our grandma we loved her and thanked her for the eight amazing children she brought into the world. During the boat ride back to shore, the sky ripped open in a reddish, purple haze, a color I never knew was possible. All you could see for miles was the horizon and the possibility of endlessly more. And at this sacred moment, maybe the most important lesson of the pandemic hit me: Somehow life continues. And the poignant words from Jojo Rabbit were replaying in my head on a loop, “Just keep going.” Now that the pandemic is seemingly coming to end, I can’t help but marvel at the fact that humans always manage to do that, they “just keep going.” Or in the words of Dr. Ian Malcolm in Jurassic Park, “Life finds a way.” And it’s my biggest hope for the world that when the pandemic is finally over, we all realize we have no choice other than to dance.

Wave Therapy: How I Stopped Living in Fear and Learned to Surf

I was born in the winter of 1996. I barely weighed six pounds, but I was eager to live. My mom had just turned 20 and dropped out of college to find a job because my biological dad "didn’t want us as his family.” Parenthood is tough, especially when performing both roles. During her pregnancy, her mind never stopped overthinking my future. She feared I would repeat her story: fear, anxiety and worry were the main characters. I don’t think my mom wanted me to become a woman who was afraid of living; however, unconsciously, she instilled fear in my upbringing. I got my daily dose of "Don't do this because it's dangerous" or, "If you do it, you could die" commands. She made sure I understood from a young age there were always negative consequences to every decision. I don’t judge the way she raised me, rather I aim to understand the root of her fear. I believe it was ultimately born of love—and not wanting to lose me—after already losing my dad. Death is a powerful word. It's something I have tried to avoid if possible. Every decision I made was a conscious effort to not risk my life, which my mom tried relentlessly to protect. While in high school, I said no to driving in my friends’ cars, smoking weed, drinking alcohol and swimming in the ocean without an adult. The list was endless. My mom had warned me of all the possible things that could go wrong if I did any of them. My mind was trained to see the negative. My instinct was always in survival mode.

I Found a Job During COVID in a Surfing Village

I admired other people's ability to do all the things I refused to do. I wanted to challenge my fear but I let it dictate my decisions. Until, one day, COVID-19 knocked on my door. For me, 2020 was a year full of challenges and personal growth. My grandmother and two of my uncles tested positive for the virus. When I looked into my uncle's eyes, I noticed death lurking. Only my grandmother recovered, while my two uncles passed away at very young ages. Losing my relatives, and the series of events that unfolded throughout last year, felt like a slap in the face. All those years avoiding danger to postpone death were bullshit. I realized death was the only thing in life that is granted, and the effects of the pandemic triggered me to start living life because a life chained to fear is not one worth living. In the midst of chaos, I got a job offer in a secluded surf village three hours away from the place I got so used to calling home. Even though adventure and exploring were not usually in my vocabulary and lifestyle, I decided to step out of my bubble. The ocean had always amazed me, but I was never allowed to swim unsupervised because it was home to "deadly sharks and currents," as my mom used to say. I was committed to learning how to surf despite my mom's opinion. My decision was reinforced after the first session in the water. Not because I became a pro in a 60-minutes lesson, but because my soul was reset in the process.

All those years avoiding danger to postpone death were bullshit.

I Overcame My Fears and Entered the Ocean

I’m not going to hide it: I was terrified of going into the water for the first time, especially at 23 years old without a relative or close friend. My mind thought about all the things that could go wrong before the lesson began. To make it worse, before going in, someone told me to be aware of stingrays because it was their season. Despite all that, I carried my board and paddled in. The feeling of riding my first whitewash wave was worth everything. After the first one, I kept going back for more. The adrenaline took over. My mind focused on being present rather than thinking about the 100 possibilities of dying. Surfing is the best meditation I have done. There is something liberating about surrendering to the power of a wave. After a lot of effort, practice and discipline, I swapped the whitewash for real unbroken waves. To catch those types of waves, I had to paddle far into the ocean and stay in the line-up to wait for my wave. The first couple of weeks, it was extremely hard to understand the waves. Surfing is not just about popping up on the board—if it were that simple, more people would surf. This sport is a combination of reading the ocean, understanding the wind conditions and having the self-awareness to maneuver the body on the surfboard.

When I’m not in the ocean, I crave the person I become when I am.

Surfing Has Made Me Happier Than Ever

A part of my personality consists of planning ahead and being in control. My first instinct was to try to control the ocean but, after many sessions, I learned that giving control to the ocean helped quell my fear and anxiety. I now respect the ocean. I understand it is a bigger force; thus, when a big wave comes my way and I don’t paddle out fast enough, I just dive under and surrender. This sport has taught me patience. My lack of experience in understanding a wave's language made it easier for me to wipe out. Waves would even break on my back. Wiping out in the ocean is not fun. I have a couple of scars and bruises that can attest to that. Nevertheless, the minor negative effects don’t outweigh the benefits. The ocean has been the therapist I was never able to afford. Nothing beats the feeling of wholeness I get when I start ducking the big whitewash to paddle my way into the line-up. I think this is the happiest I have been in a very long time and it's due to surfing. I feel the endorphins released as soon as I catch my own unbroken waves. This sport has the effect of a drug on me because it keeps me going back for more. When I’m not in the ocean, I crave the person I become when I am. I understand life itself is an adventure. I want to keep living my adventure and make up for all the years I was a prisoner to my own thoughts fueled by fear.

I Grew Up in a Palestinian Refugee Camp

During the Nakba in 1948, when there was a mass exodus of Palestinians expelled from their own houses and lands in the place that right now is called Israel, around 3,000 people built tents in my neighborhood on the borders of Al-Bireh. My family are natives of the city and have been living in the same place for decades. Over time, as the camp grew and became more rooted, we found ourselves surrounded by crowded concrete buildings populated by more than 10,000 people, with my house in the middle. We found ourselves as a family living in the extreme conditions of our neighbors, plagued by overcrowding and inadequate sewerage and water networks. Despite the change, my family has always been welcoming to our refugee neighbors. The crowded conditions haven’t dampened the inhabitants’ genuine caring and natural bonding, which have made them resilient and steadfast. I have been told many stories about my grandmother. She was the godmother for the camp, who opened her house to those who needed help and defended her young neighbors from Israeli military attacks with her special weapon: her slippers.

I remember the sounds of bombings, shooting, arrests, and Israeli tanks and troops in the middle of the night.

My Homeland Is an Open Sky Prison

I lived through the Second Intifada in the early 2000s. I was five years old when it started. I remember the sounds of bombings, shooting, arrests, and Israeli tanks and troops in the middle of the night. I remember the shouting and wailing of mothers for the lost lives of loved ones. I witnessed my dad being arrested by Israeli soldiers. I wondered at the time where they were taking him, and if they would take me as well. Later, my mom calmed me down and told me he’d come back. After a week he did, with tears in his eyes. I didn't know what happened and no one told me. Now I am 26 years old, and I still don't feel safe. The regular midnight raids on the camp scare me. Since childhood, my worst nightmare is a tank demolishing my family house over our heads, the way I see happening to our neighbors. Living an everyday life is a dream to me. I ran to Ramallah to find a decent job where I can fulfill my dreams, but the brutal reality keeps chasing me because big cities are not far from political events. Settling down seems impossible when one day you have a job and the next you don't.

It is an apartheid wall, segregating people from each other based on identity and race.

The Wall Divides

When I want to travel from one city to another through military checkpoints, young soldiers no older than 19 point their guns at us, ready for any ambiguous move to give them a reason to open fire. I have to carry all my identification documents with me every time I leave the house, even for a short trip. Usually, the drive from Al-Bireh to Nablus takes an hour. Sometimes, we have to roam for six hours to reach my relatives' house in Nablus, crossing one checkpoint after another. Having my belongings searched by soldiers, or even being given a full-body security scan, has stripped my feeling of safety and personal privacy. In my short lifetime, I have seen the wall built around Palestinian cities and villages, disconnecting them from relatives and friends, and zoning them into fragmented IDs. To me it is an apartheid wall, segregating people from each other based on identity and race. I live one hour away from the sea but can't reach it because I need a permit from Israel. I have never been to the beach. How do I see the world? Through the eyes of my foreign friends who tell me stories about their countries, cultures and lives without borders. It confuses me. I don't know if it makes me happy or sad to hear how easy life is supposed to be. I am overwhelmed by the fact that the world is moving and I am standing still, gathering my shattered, sabotaged dreams. It is depressing to live in a reality where human needs are only measured by what you do today, not what you aspire to achieve tomorrow. In the end, my only consolation is hope.

Shotgun Stories: What It’s Like Without a Driver’s License at 30

It is my incredibly biased, objectively incorrect, but firmly-held belief that if you make it to the age of 30 without acquiring a driver’s license, you should not have to take a test to be issued one. You have already proven that you are not jumping rashly into this. Nevertheless, until the DMV gets on board with my policy change, I’d like to introduce myself, the 30-year-old without a driver’s license.The year is 2008. I am 18, recently graduated from high school and my braces have recently been taken off. It’s summer in Portland, Oregon, and I’m working most days at a running store, fitting people in shoes and watching track races from the '80s on YouTube with the passel of fit, smart twenty-and-thirty-somethings who treat me as half-little sister, half-peer—and teach me most of what I will ever learn about running. I am near-drunk on free time, warm air and the big sky open plains of my life spread before me. I’m sunburned and muscly. And then there’s Matt, one of my coworkers at the store, seven years older than me. He’s the goofiest, most interesting person I’ve ever met. Almost overnight, we go from emailing each other funny articles to running together a few times a week. He picks me up from my house or the store and we go up to Forest Park. I don’t, you’ll recall, have a driver’s license. Sometimes we stop for a bagel on the way home. Sometimes I offer him a smoothie when he drops me off. Once, after an evening run, while driving home through the pink-orange sunset and clouds of sluggish mosquitoes, he puts on “Elephant Love Song” and we sing along at the top of our untrained lungs. How wonderful life is, I finish, in a falsetto that cracks, now you’re in the world. I know what you’re thinking and the answer is yes, we turned out to be in love with each other. A couple of years later, he will drive up to Philadelphia to visit me on my spring break and, after dinner, as he’s driving me home, caught up in conversation in the dark, neither of us will realize he’s taken a wrong turn until we cross a state line. I will jokingly accuse him of absconding with me and we will both laugh as he gets off the freeway to go back, and we will both secretly wish he could take me all the way back to Virginia with him.

I’d like to introduce myself, the 30-year-old without a license.

Driving With Someone Is One of the Most Intimate Ways to Travel

How often do you ride in a car? I don’t mean an Uber. I mean a car driven by someone you know, with you sitting in the passenger seat, fiddling with the radio, giving directions, providing the right amount of conversation, letting yourself be ferried from place to place. It’s a surprisingly unusual position for most adults, except for a certain subset of heterosexual women who, like my mother when we were kids, never drive when their husbands are in the car. And except for me.There are so many ways to cross this wide planet. But surely this is one of the most intimate. Ensheathed by night on all sides, reflected back to yourself in the windows, or at the copper twilight hour, a world is created unto itself for the length of a trip. Once, I went with an acquaintance to get coffee, just the two of us, and in the space of that 20 minutes across Queens on a Sunday morning, we cemented a fond respect in our shared tastes in books and music and affection for our mutual friend.

My Romantic Ride to the Beach

The year is 2018. Another summer. I am 28, have graduated college and quit the job that became a career. I’ve taken my savings and flown to Europe. It’s a hot, humid night in Palermo: The air is so thick and soft you could use it as a pillow. I have had two glasses of wine and an anchovy panini at the bistro around the corner from my apartment where the owners, bartender and waitress have come to know me. I’m sitting at the bar and the handsome, curly-haired Italian man I’ve been trying to make sexy, googly eyes at over the last few nights comes up next to me to order a beer. Empowered by white wine and Mediterranean salt air, I start a conversation. At some point, he compliments my Italian, and then I know I’ve got him because that’s bullshit—my Italian is five common phrases and then a bunch of Spanish that Italian people can mostly understand. I explain in my personal creole of English, Spanish and per favore that I haven’t been able to go to any beaches outside of Palermo because I don’t drive. I’m not, I swear to you, trying to hint at anything, but he offers to take me to a beach for locals the next day. None of the touristy places. I’m in heaven.But I don’t want to suggest that all rides home or across town—or for hundreds of miles—are romantic. They can also be the most platonic of experiences. I have also been the recipient of many well-meaning rides from coworkers, teammates and even occasional strangers. There was the woman who saw me struggling with an A/C unit in the Brooklyn Home Depot parking lot and drove me the ten blocks to my apartment. Or my canvassing partner in Atlanta, who drove us all over the Democratic areas in a pandemic, each of us in masks and face shields. We spent ten hours a day together and never saw each others’ noses. Even the boss I have now, who regularly drives me to my apartment in Brooklyn from our office deep in Queens, allows me to scan through radio stations for a song I like. I eventually land on Billy Joel’s “Longest Time” and snap in time, allowing him to drive out of his way to get me to my front door without any input on the music.

I’m in heaven.

I Will Always Cherish My Time in the Passenger’s Seat

Strictly speaking, I can’t recommend living without a driver’s license in the 21st century. There are jobs I’ve missed out on because of it. There are hours I’ve spent waiting for subways and buses. When I sat down to think about the grand adventure of moving through the world on my own two feet, I thought first of the possibilities it cut off. About being stranded in the middle of the countryside outside Palermo. About not getting to take day trips outside of Paris or hikes outside of Portland or even rent a Zipcar—that most important middle-class New Yorker ritual— and go to Storm King Art Center on a fall day.But when I thought further, all I could think about were the countless cherished hours of conversation in the passenger seat of someone else’s car. One day, and hopefully soon, I’ll get my driver’s license. I’ll make an appointment and go into the DMV and take the test, with the backs of my thighs sweating on the polyester seat. And it will be nice to have an added transportation option. I will love driving to a trailhead and leaving a clean, dry change of clothes in the trunk while I run. I will try to pay forward the thousands of rides home I’ve been given. But I can’t regret the extra 15 or so years of passenger seats, when a driver moved a pile of stuff to the backseat, murmuring apologies for the mess, ready to be enclosed together, a moving universe of two. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Firewalking: My Baby Died in My Arms and My Partner Blamed Me

At some point in the past, I heard about an activity called firewalking. Those that do it have to work for months to build resistance on their feet before they’re able to walk on extremely hot coals in places like Hawaii. It’s uncomfortable and painful but, over time, their feet adapt and are able to make it look easy. I think that’s a good analogy for how I handle the emotional stress in my life. Most of it just feels like training. The longer I live, I build up calluses to some of the most heartbreaking and earth-shattering events, and I keep meeting people who have seen different kinds of tragedies in their life. More often than not, their experiences make me question the gravity of my own. They’ve planted an empathy in my soul that’s made me conscious and careful about whom I lend my concern but, once I do, understanding and compassion blossom in a way that makes it hard to put into words.

We’re all subject to the perspective of whatever we experience—no one’s process is any more or less valid than another.

The Severity of Pain Does Not Diminish Its Validity

It’s taken years and a lot of good friends to teach me not to compare my own pain to others. There are people who have experienced trauma from a sibling constantly knocking their ice cream to the ground as kids, and that’s just as valid as someone who’s visibly seen a child die. We’re all subject to the perspective of whatever we experience—and no one’s process is any more or less valid than another. I wish I could repeat that sentence over and over again so as a culture we could decide collectively to never be dismissive of someone else’s experience. No matter what story people share with me, I make it a habit to understand how they process it. It’s so important not to judge the gravity of someone else’s experience because what could be an anthill to one person could be a mountain to someone else. True connection comes from seeing it as they do, not as you do. I’ve never experienced ice cream pranks with a sibling, but I have experienced a child dying—twice, in fact—and I can tell you that nothing prepares you for that. For nine months, as your baby is on its way, it’s easy to think about the kind of parent you’ll be. There is so much joy and desire to celebrate every day because another person loves you enough to bring new life into the world with your name. To have that taken all away can really make you question a lot of things.

How My Son Literally Died in My Arms

The date was September 4, 2008. My partner and I had gone to sleep as usual, with our five-week-old son asleep on my bare chest. Every other night, when I could hold him and talk to him, I breathed over him a prayer for all the things he would be one day. I listened to his breathing so I could feel in sync with the rhythm of his every breath, for as long as I could. I was so thankful to be a dad. When morning came, however, something was off. He was still warm as I slowly rose to wake him for his breakfast but he wasn’t moving, and his chest had stopped the normal rising and falling at some point while I was asleep. Rubbing the sleep from my eyes, I reached for my glasses and couldn’t find them, choosing instead to see him as best I could with my nearsightedness. Was that blood coming from his nose? My partner, in a frantic yelp, exclaimed that his face was blue. When did that happen? Where were my glasses? I tried to do whatever version of CPR I could remember, being careful of my strength so as not to crush his fragile chest. My partner was screaming something. Cover his nose? Breathe into his mouth? I felt for the air entering his lungs to come back out, to somehow let me know there was a chance of reviving him, but I knew. I looked at her. She was still panicking, but I already knew. He was gone.

He was gone.

Acknowledging the Close Connection Between Grief and Blame

I stumbled woodenly out of the bed and through the bedroom, trying to find the lights. Where was the phone? I had to call 9-1-1. The power was out, my phone was non-existent, hers hadn’t been paid. I needed to find a phone. I made my way through the little apartment complex to the payphone on the street and dialed. I didn’t know what I sounded like, and there weren’t any words to share. I had no idea what to do next, and even now remembering it, I still don’t know how I made myself finish that call and walk back into the house. My partner had wanted me to save him and I couldn’t, and now, once she figured out what happened, I knew what was coming. As I said, nothing prepares you for that. I wasn’t ready for Devin’s death, and I wasn’t ready for my partner thinking I killed him. By the time the paramedics came to ask me what happened, I had resigned to a few outcomes that were not good, and I was still processing a lot. If this was my fault, I was prepared to face the music. It would have been nice to have the person who I loved to offer a word of support and some belief that maybe there could be another answer. But it wasn’t to be had at that moment. I had a partner who was also grieving but didn’t know what happened and thought I was at fault.It would be another two weeks before I’d discover we lost our son to SIDS. But for two weeks, in her mind, I was a murderer. That was a mountain for both of us, and the choice I made to do my best—to be my own support rather than ask her to have a little faith that there was another answer—took more inner strength than I ever thought. To look someone in the face who is accusing you and choose to love them rather than lash back—to look for clarity and understanding rather than bitterness and indignance—takes a kind of inner fortitude most people only discover they have at a moment like that when they need it.

Coping With Losing a Baby to SIDS

One of the things that helped me get through it was actually heartbreaking at the moment. I had to forcibly tell myself that it wasn’t my fault and that expecting anyone else to support that understanding wasn’t their responsibility. Let me repeat that. Even if you’ve been with your partner for years, and have shared everything together, it’s not their responsibility to give you the support you’re looking for when you go through loss. We all have to decide to be responsible for how we feel about anything. In part, I think when tragedy strikes, a lot of people want someone to understand, and for people to empathize, and it’s nice when that happens. But what about when it doesn’t? What about when you go through the hardest things in your life and nobody understands? Or worse, they ridicule you for it? As long as I was susceptible to others’ support or lack thereof, it was crippling. So I started to make a habit of realizing that I might be the only one who understood what happened and just be OK with that. Putting that kind of pressure on someone who is also grieving may be something they’re not ready for—or something they don’t have the emotional capacity to offer. Learning how to be your own comfort when things go horribly wrong is a really helpful skill, and becoming that kind of friend to other people during hard times made it easier.

Losing a Child Doesn’t Have to Mark the End of Parenthood

When my first child died, I thought back to all the times I’d dreamed of having a son, and why I wanted to be a dad in the first place. I thought about all the things that I would do with him and teach him the way my dad taught me. Thankfully, I have a really attentive dad, so I have plenty of memories to reflect on, like riding around our small town in New Jersey on the back of a bicycle, like the kid from Peanuts whose mom is always running into trees. (My dad never hurt us, but the resemblance is hilarious and familiar). All of those things that I wanted to become were still present, I just couldn’t be those things with him. I was going to have to wait and hope I’d get another chance. And it’s in that hope, and the belief that I’d get another chance, that helped me get through that. I immediately recognized that it could be a completely different situation. Maybe I’d have to adopt or become a foster parent, or maybe it could be some other circumstance. But being in that situation prepared me to be ready to give my all to whatever situation came.Personally, I think that’s what suffering is supposed to do—help us find ways to support others who have gone through similar experiences, to be encouraging and inspiring to one another when we reach our lows. A wise person said to me that “We’re more alike than not,” so I’ve constantly looked at my challenges and tried to evaluate who I wish I was, were I in the other person’s shoes. I don’t recommend going through that kind of emotional training on purpose, and hopefully, whatever fire you walk through won’t be anything like that, but finding your inner strength can give hope to someone else. It’s one of the greatest gifts we can give.

I Lived in Sheikh Jarrah; What I Saw There Shocked Me

I am an American who has lived in Sheikh Jarrah, the East Jerusalem neighborhood that has been making headlines recently as it has triggered protests leading to bombing and more violence in the Israel-Palestine “conflict.” Before moving to Jerusalem, I liked to believe that I had a neutral stance on the conflict. In my last year of studies, I was offered an internship with a UN donor agency in Jerusalem. Growing up in the States, I had always heard how amazing Israel was from my Jewish friends who did Birthright and voluntary service with the Israeli Defense Forces. I am embarrassed to admit, I moved to Jerusalem without actually studying, reading or understanding the history of the city. I was raised culturally Catholic, and all I knew was that Jerusalem was equally important to all the Abrahamic religions. At the time, all I really knew about Palestine was war-torn Gaza, which I thought was only in a conflict because of Hamas’s Islamic terrorist control over the territory. Israel has a right to defend itself from terrorists—that’s what we always heard in the U.S., and that is what I strongly believed. When I landed in Tel Aviv, my organization sent a driver to pick me up at Ben Gurion Airport. As soon as I saw him holding my name I went up to him and happily said, “Shalom,” to which he replied, “Sorry, I don’t speak Hebrew, only English. I am Palestinian.” My first thought was, how could a Palestinian be allowed inside Tel Aviv? I thought they only lived on the other side of the wall, in the West Bank or Gaza. I am grateful for the patience of this man, who answered all my ignorant questions on our drive to Jerusalem without any pushback or anger. He explained to me that he was born in Jerusalem, as were all his grandparents and great-grandparents, and that he had an Israeli “blue I.D.,” which gave him permission to live in Jerusalem and travel around the rest of Israel. “Wait, you need permission to live in the city where you and your grandparents were born?” “Yes, because Jerusalem is now controlled and occupied by Israel, but Israel does not recognize me as a citizen because I am not Jewish.” I tried to act intelligent and understanding, but I am sure my look of utter confusion was obvious. “I know, it's all so complicated and difficult to understand,” he said. “But soon you will see the truth.”

What the fuck was this place?

Life in Israel Was Not What I Was Led to Believe

My office and home were located in the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. In my first days living there, I would constantly get lost. I didn’t understand why the map had so many dotted lines surrounding my neighborhood, nor what they meant. Then I realized they marked the Green Line from the 1949 Armistice Agreement. While trying to figure it out, I learned that I was living in what was supposed to be left of Palestine’s capital. I read more—enough to understand that Jerusalem was half Israeli and half Palestinian, and that I was living and working in East Jerusalem, which is on the Palestinian side. But wasn’t the wall supposed to mark the Palestinian border? Why are there Palestinian neighborhoods on the Israeli side of the wall? I kept reading and asking.On my first day leaving Sheikh Jarrah, I wandered onto the tram to explore Jerusalem’s Old City. I got to see a vast variety of people: Jewish men with their long beards, curls and black hats; Muslim women in hijabs and abayas; and a lot of hipster-looking youth. Among the youth, many were holding rifles, although they weren’t in uniform. As the tram filled up, I was squished into a door. A young girl came running on and accidentally hit me with her rifle. What a radical feeling, to be hit in the chest with what appeared to be an AK-47 held by an adolescent girl. I locked eyes with her in absolute shock, as I had never had a rifle so close against my body. She looked the other way and didn’t even say sorry. What the fuck was this place? When I finally got to the Old City, I was disappointed. I had imagined a charming, lively market, but instead came across a checkpoint with a bunch of soldiers and military cars at the entrance of Damascus Gate. There were even Israeli soldiers at the door of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. And the intimidating sights only worsened when I finally crossed the wall into the West Bank. Being raised Catholic, my whole life I had sang Christmas songs about Bethlehem. I was so excited to finally be able to see the city where Jesus was born. I took a bus from the city center of Jerusalem that dropped me off just 30 minutes away. And there it finally was: the wall.In order to reach the Nativity Church, I had to cross the wall and go through a military checkpoint. I went through four turnstile doors, under what appeared to be a cage, just to enter the town where the Messiah was born. I had always thought of the Israel-Palestine war as a religious one between Jews and Muslims, but I never imagined it was also affecting the religious freedom of Christians. Later, I made the mistake of telling an airport security worker at Ben Gurion Airport that I had been to Bethlehem to visit Jesus’s birthplace, which then led to an hours-long interrogation. “Do you have friends in Bethlehem? Why did you go there if you knew it was in the West Bank? Did you take an Arab bus to get there?” “Yes, I took the Palestinian bus to get there.” That was a mistake. The officers replied angrily that there was no such thing as a Palestinian bus “because Palestine does not exist.” (That was the first of hundreds of times I heard an Israeli say that. There are, indeed, both Palestinian and Israeli buses, with differing routes.) I spoke to Arabs, because all the priests in the church were Arabs, because Bethlehem is in Palestine, and therefore there are Palestinians that are Christian and Catholic. What was wrong with that? Don’t I have the same right as a Catholic to see Jesus’s birthplace? After all, any Jewish person can get a passport to live in Israel. Why was I getting in trouble for going to see where Jesus was born?

Violence in Israel Is Inescapable

I tried to make Israeli friends. I visited Tel Aviv frequently to escape the tension in Jerusalem. But even in the vegan restaurants and gay bars, or while smoking joints at the beach, almost every single time I was honest to an Israeli person about my humanitarian work, they were quick to brush me off as a terrorist or anti-Semite. Many taxi drivers in West Jerusalem would refuse to take me to Sheikh Jarrah because “that’s where the terrorists live.” I started to lie to them and say that I was going to a hotel near my house. It became more and more evident that Israel wasn’t the amazing democratic paradise the U.S. paints it as. Every week, I saw Israeli soldiers do something terrifying. The most notable was the violence against children: I once saw Girl Scouts getting pushed around by soldiers at gunpoint. “Why do they do this to children?” I sincerely asked Israeli people. “Because they throw rocks and they are dangerous.” I literally got hit in the chest by an AK-47 held by a teen, but somehow the real threat is little kids throwing pebbles? The saddest part is, these Israeli teens have to do military service or go to prison. Without proof of completing the military service, they risk not getting jobs or apartments in the future. How could this be called a democracy?I expected to see some violence against Palestinians, but I never imagined the levels and frequency of it. I saw soldiers throw cans of tear gas at a crowd in the checkpoint; the image of a mother running from the gas while covering her toddler’s face with her hijab will haunt me forever. I saw elders humiliated and insulted by 19-year-old soldiers in never-ending lines under the scorching heat, begging to enter the cities they were born in. But the violence wasn’t just against Palestinians: I was once riding in a UN car in the West Bank when we had stones thrown at us by Jewish settlers. These are the people living in illegal, government-funded settlements in the West Bank, on the other side of the wall, in what is technically legally supposed to be Palestinian land. They hate the UN and any organization trying to respect the original border treaties. What was the point of all these treaties and a huge wall if they want—and allow—Israeli people to live on this side? The settlers don’t have to cross the wall and checkpoints because they have their own roads that are protected by soldiers. Apartheid is the only word for it.Although violence against humanitarian workers was shocking, it wasn’t the most shocking. What finally made me completely stop defending Israel was witnessing violence against the Orthodox Jewish community. We know that Israel was created to provide Jewish people a safe homeland after the Holocaust. We hear the words “Israelis” and “Jewish people” used interchangeably, particularly by Netanyahu himself. (Let it be known that the majority of the world's Jewish population lives outside of Israel.) We hear that Israel has a right to exist because Jewish people deserve to be safe. I decided to visit the neighborhood of Mea Shearim to get a closer perspective of how the Orthodox community lived. When I got there, I could hear singing and chanting. As I turned the corner, I saw a scene like something from a horror movie. Dozens of Orthodox men, with their payots (curls) and shtreimels (hats), running away from a tank that was headed towards them. The tank was hosing them down with a malodorant—the smell was so disgusting I could smell it from the end of the street. Some of the men were getting hosed so hard they were literally flying through the air, another image that haunts me until this day. I learned that the Orthodox Jews were protesting against an army draft being held in the area. They aren’t forced to do military service like other Israelis are, but there are still efforts to get them to voluntarily enlist. They didn’t have rifles like the other Israeli youth. They were singing and chanting in what was obviously a nonviolent protest, and the army came in and hosed them down with chemical skunk water. I learned that sadly, this is quite a frequent phenomenon. On YouTube, you can find plenty of videos of Orthodox Jews being hosed down by the IDF. It doesn’t seem to me like Israel is a safe place for all Jewish people. The state uses terrifying violence against some of the most religious Jewish people, yet I got called anti-Semitic for asking why the army harasses Palestinian children.

It became more and more evident that Israel wasn’t the amazing democratic paradise the U.S. paints it as.

My Time in Israel Changed My Perspective

It is clear to see that this is not an issue merely between Jews and Muslims. This is not a complicated religious conflict. This is not a “war,” because only one side has state-of-the-art military equipment paid for by U.S. aid. This is clear apartheid, and under international law, it also constitutes war crimes. There are children being killed and arrested on land where the Israeli army has no jurisdiction. Sheikh Jarrah is not a “real estate dispute”—it is being occupied and colonized. The people of Gaza suffer more under the rule of Hamas than any Israeli person does. There are Jewish people being called anti-Semitic for standing against Israel’s right-wing government (see: Bernie Sanders). Israel, with its powerful lobbies, is so good at pushing its agenda—they are world leaders at spying, censoring information and promoting propaganda. They have done a fantastic job at convincing the world that if you don’t agree with their policies and violent tactics against the Palestinian people, then you are an anti-Semitic terrorist supporter. I wish all people could see the truth with their own eyes the way I did. This is about human rights abuses; good versus bad. And in case it wasn’t obvious from all of the videos of violence making their way out of Sheikh Jarrah and beyond, the bad guy is Israel.

What It’s Like Being a Doctor During Ramadan

“You can’t even drink water?” This is one of the most common questions I get asked while fasting during the month of Ramadan. Once a year, over 1.6 billion Muslims worldwide adhere to the holy month of Ramadan, which never occurs at the same time of the year since the Islamic calendar is lunar-based. As a child, I remember fasting in the wintertime, when we would open our fast around 4 p.m. right after school. During my residency training, I recall 17 or 18 hours of grueling fasting during the dead of summer. Either way, the feeling of clarity, spirituality and closeness to God we get from our fasting is always met when the month comes to an end.During the month of Ramadan, Muslims are expected to abstain from food, water and sexual relations with spouses from dawn until sunset. Every night, people congregate at a local mosque to recite a special prayer. Many people say this tradition is to appreciate the blessings of your life and to know how those less fortunate than us may have it on a daily basis. But this is not the core reason as to why we fast. We fast so that we may increase our awareness of God and become more “God-conscious.” The analogy I give my friends and co-workers is that if I’m alone at home, or in the office, and I’m hungry or thirsty, then what’s stopping me from eating or drinking? My parents won’t know I had a sip of water. My friends or co-workers won’t know either. But we believe that God is always watching us, and so we refrain from these things. It’s this exact same sentiment that should carry on to our other actions in life. If we decide to lie, we’re reminded that even if no one else may see us, God is watching. If we are going to cheat, or speak maliciously about someone, He’s watching. This fasting mindset should carry over to our daily lives so that we may improve our character and be more upright.

We fast so that we may increase our awareness of God.

Fasting Has Given Me Better Clarity and Focus

As a physician, I regularly prescribe patients intermittent fasting to help numerous medical conditions. Many studies have shown that intermittent fasting (also known as “wet” fasting since you can drink water and black coffee or tea) has shown to decrease blood sugar levels, lower cholesterol, aid in weight loss and even help lower blood pressure. I remind my patients that there is not one single medication or pill that I could prescribe that would give them all of those benefits. But fasting does. People often wonder if fasting affects my ability to care for my patients, and I let them know that it does the opposite. There is a clarity that comes from fasting that requires the human mind to set aside the feelings of hunger or thirst and to better focus on the task at hand. In fact, there are professional athletes in the NBA, NFL and soccer leagues around the world who tend to perform at an even higher level during the month of Ramadan than outside of it.

People often wonder if fasting affects my ability to care for my patients, and I let them know that it does the opposite.

My Ramadan Practices Have Helped Me Through the Pandemic