The Doe’s Latest Stories

When I Stopped Driving My Daughter, I Lost Purpose as a Dad

"I passed!” My 18-year-old daughter texted me, and suddenly, she could drive. I was relieved because she had failed the test twice and was getting increasingly cranky about it. I was also relieved because I have spent the last 18 years as the primary child-conveyor/transporter/sherpa. When she becomes friends with someone on the other side of the city, it is me who transports her tiny and then less tiny and then full adult-sized body to the doorsteps of the friends who also, over the years, have increased in height. If she is performing in a play in the suburbs, it is me who drives 45 minutes suburb-ward and then sits in the parking lot until the suburbs are done with her to transport her back to her rightful home with all the cats, because driving another hour-and-a-half round trip is even more unpleasant.Squatting in a suburban parking lot (or, if you’re lucky, at a suburban Starbucks) is, as you’d imagine, a somewhat tedious way to spend the waning years of your existence. You gaze across the strip mall at the SUVs and you may ask yourself, like David Byrne, “Well, how did I get here?” You may turn to your daughter and say, “This is not my beautiful Prius!” And she’ll respond, “…” because she’s not paying attention to you. She’s on her phone.

I have spent the last 18 years as the primary child-conveyor/transporter/sherpa.

My Daughter Had Some Setbacks When Trying to Get Her License

Since David Byrne asked, I can say that I do know broadly how I got here. First, we had a child who was adorable and tiny and largely unable to get herself around on her cute, pudgy, but initially largely vestigial legs. Then, we distributed various household tasks—my wife agreed to make more money, provide health insurance and shop for pleasing apparel for the incipient human. And I agreed to get the duly clothed critter to whatever clothed-critter activities should arise over the next roughly decade and a half.Initially, we thought this was a 16-year or so commitment. But—as you probably guessed, since my daughter is 18 and not 16—there were complications. Our city makes it difficult to get your license right at 16, but we gave it a good shot. She had driver’s ed. She had driving lessons with professionals who were not us. She had her permit. She was practicing and I hadn’t actually had a heart attack when she drove the car that close to the parked cars on my side—oh my god you’re too close pull over OH MY GOD!Where was I? Oh, right. No heart attack, nope. Right on track to the DMV.Then, COVID hit. The DMV closed. We spent all day, every day sitting in the house staring at the dog rather than sitting in parking lots staring at SUVs. And I like the dog better than SUVs. But still, it was a setback.Then, as a setback to the setback, my daughter went on a trip to a friend’s cabin and said friend (perhaps on controlled substances of various sorts) tipped the canoe, leaving our daughter’s phone and her permit in the phone case at the bottom of a lake.Said friend was sincerely sorry, and we did not reprimand them because we like them and kids, what can you do? But now we had to go to the DMV and get a permit before we could do more hair-raising driving practice and then take the driver’s test. The additional step proved too much for us for…well, a good long time. A good long time also being coincidentally the exact distance between our house and my daughter’s various extracurricular activities. Also between our house and the home of her significant other. How could you even find a significant other who lives that far away when you’re in high school? “What happened to dating the girl next door?” I asked her as I stared at the very large SUV looming over our Prius.“…” she said, because she was not listening to me because she was on her phone.It was the significant other who finally did it, though. I do occasionally have other things to do with my life (like drive my wife places, for example), whereas my daughter wants to spend her summer with her significant other literally all the time because she’s a teenager and that’s what teenagers want to do. Thus motivated, she got her permit, took some driving lessons and headed to the DMV. Then to the DMV again. And finally to the DMV and passed so she never has to go to the DMV again, thank god. She is driving now without us in the car, so we do not see her when she almost hits things, which is not ideal but maybe better than being in the car when she almost hits things, overall.

I got here because I love my kid and I want to make her happy. If I’m going to waste my remaining years, that’s not a bad way to waste them.

I Enjoyed the Time I Spent With My Daughter While Driving Her Around

At last, for the first time since I lifted the small creature with the vestigial legs and transported her from bed to crib, I am free. She is self-propelled and needs me no more. Huzzah!Right?Well, sort of. I don’t relish sitting in Starbucks parking lots for hours on end. But on the other hand, when you lift the incipient human and she blinks and screws up her face and then spits up on your shoulder before settling down, you do feel like you’re serving a useful function. I may not exactly want to stare at the back of an SUV creeping toward the home of my daughter’s significant other, but when David Byrne asks, “How did I get here?” I have a ready answer. I got here because I love my kid and I want to make her happy. If I’m going to waste my remaining years, that’s not a bad way to waste them.Driving the child has other upsides too. It’s true she has a powerful ability to ignore her chauffeur and concentrate on the latest text from that significant other instead. But the Prius is quite small and she is trapped with me in there. At home, she can emerge only briefly for food or to open the door for friends before skittering off to her basement, like one of the cats escaping but with less floof. But in the car, sometimes, despite herself, she’s got no choice but to interact with me. Recently, we got to talk about what an awesome drummer Chris Frantz of Talking Heads is, for example. She tells me what she’s reading (Jules Verne, most recently. “Is it good?” I asked. “Sure! It’s Jules Verne; it’s got energy!”) She bubbles about a production of Marlowe’s Faust she and the significant other and the friend who drowned the permit and some others are planning to put on. Talking to her is fun. Even better than when she used to spit up on me (though not necessarily than when she used to cuddle up afterward).It's great when your kids become more independent and need you less because then you can heave a sigh of relief and go back to your own pursuits—like contemplating the empty hole in your life left by the fact that your kids need you less. First, she can crawl to the next room; then, she’s taking herself to the park; and finally, she’s out of her room and out the back and out of the garage and into the whole world. You wave goodbye. Then, you get ready to walk the dog. Good dog. You still need me.

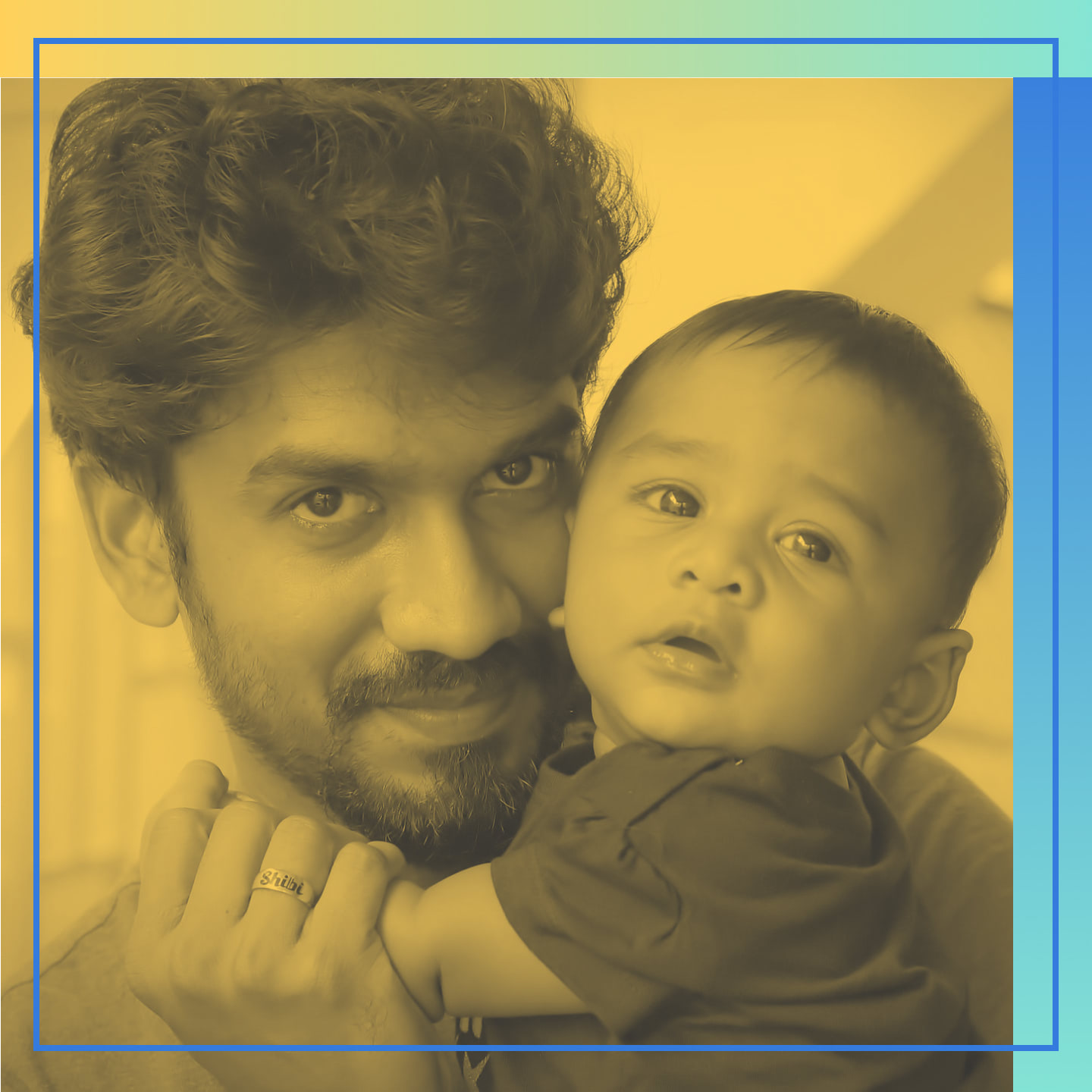

I Am a Stay-at-Home-Dad and I Am Proud of It

Even in the 21st century, it's difficult for society to accept a couple in which the man stays at home to manage the house and kids and the woman goes out to earn. Gender stereotypes are still deeply rooted in people’s minds.

Staying at Home With Our Daughter Works Best for Our Family

My wife works as a metro train operator, and I work as a content creator for a nonprofit organization. The nature of my work allows me to work from home, while my wife has to go out daily, commute to the station and then travel across the city. We both enjoy what we are doing and take pride in our work. We share a loving bond. We have been happily married for the last six years, and we have huge respect for each other and for the roles we play in managing our house and our daughter. Over time, as our careers have moved forward, we figured out the roles we would want to play in living together. I had laid the groundwork for being a stay-at-home dad by once joking about it to my wife before our marriage, telling her that: “I don’t think I’ll be able to ever work from an office without missing and worrying about the safety of our first child.” My wife and I talked about our general desire to have a parent be her primary caregiver, but it was always with the understanding that it was my preference to fulfill that role and not my wife’s. And after our daughter was born, because of my wife’s busy schedule at work, in the initial weeks, it was I who started taking care and spending more time with our daughter compared to my wife. It was I who started setting up the food, hygiene and sleeping time for the baby and managing my work accordingly. Gradually, it became very important to me to be with her, so somehow, with my initial efforts, we had child care miraculously lined up through sheer determination and luck. For me, on a day-to-day level, just moving through the day with a joyful and exploratory sense of adventure and my family falling asleep peacefully and well-fed is a great success. I’ve never felt overwhelmed with the work and responsibilities I have in taking care of our house and daughter, as my wife and I try our best to support each other in whatever way possible—sometimes even without being asked for help. That’s the level of understanding and empathy we share between us.

It certainly raises eyebrows and causes heads to shake.

Our Neighbors Make Fun of Me for My Choice

But I’ve had to defend my choice to stay at home! It certainly raises eyebrows and causes heads to shake. Being a stay-at-home dad requires being a team player, ignoring sexist stereotypes and putting most of your ego, some hobbies and interests aside for a bit and seeing the big picture. Our neighbors laugh at us and ridicule us, as they find it really strange that I stay at home, cook food, take care of the child and plants, do cleaning and wash clothes—all the while my wife is operating a metro train and traveling across the city, carrying hundreds of passengers safely to their destinations. During a social event in our neighborhood, one representative from each family was supposed to bring a homemade sweet and put it in front of our common peepal tree and gather there to worship the tree together in a circle. I had gone with the idea that maybe by this, I’d get to talk and introduce my family to everyone. But since I was the only man there in the gathering, our neighbors started calling me names, and I clearly heard one of them calling me “woman of the year.” It was humiliating. We get ridiculed by the society members where we live who, still after centuries of economic and social development, are fixated on the gender-based roles that they have created in their minds without any openness to hear new ideas. Changing mindsets is difficult and almost impossible for those who are not even open to hearing the different perspectives. Now we are not invited to any gatherings of the neighborhood group anymore. After the peepal tree incident, there was another instance where my wife and I got heckled by the neighbors on our way to the main gate. We decided to fight back to defend ourselves from the mocking, which resulted in the society committee unanimously deciding to ban us from any social gatherings, which is ironic, as the society committee exists with the sole aim to bring families together for peace and harmony and to support each other in any kind of adversities. Of course, my wife and I felt dejected by this decision and the behavior of the members, but we take pride in our choices, and we try to be happy in our small family of three.

I clearly heard one of them calling me 'woman of the year.'

Being a Stay-at-Home Father Isn’t Stressful

A lot of people, before the baby was born, asked me if I was sure I wanted to do this. My mother would ask me if I was sure I wanted to do this, if I realized what I was getting myself into. Now sometimes, my friends, distant relatives and colleagues ask me how it really is being a stay-at-home parent, and I tell them that it can be hard and definitely tiring and frustrating, but it’s never stressful. I feel lucky to be in this situation. We together want to raise our child to be an open-minded and empathic person who will have the courage to accept the differences in the perspectives of the people in the world.I always had a very unloving relationship with my own dad, where most times, communication issues were compounded when both wanted a better father-son relationship but neither one knew quite how to go about it. He wasn’t super emotionally giving but was certainly not a bad parent; he always took care of all my material needs. To know that my daughter is going to be so much closer to me than I am to my own dad makes me really happy. People always say they want to learn from their parents’ mistakes in raising their kids, and I feel like so far, I’m doing that by having my daughter growing up close to me emotionally, and that feels really amazing.I believe we should celebrate the ever-changing role of fathers in society. Stay-at-home dads aren’t just looking after the baby. We are the feeder, the storyteller, sleep negotiator and much more. We aren’t trying to be mums, and stay-at-home dads shouldn’t ever be perceived as a threat to the role of mums. Both parents have a role to play, and stay-at-home dads should be encouraged and celebrated, not prejudged.

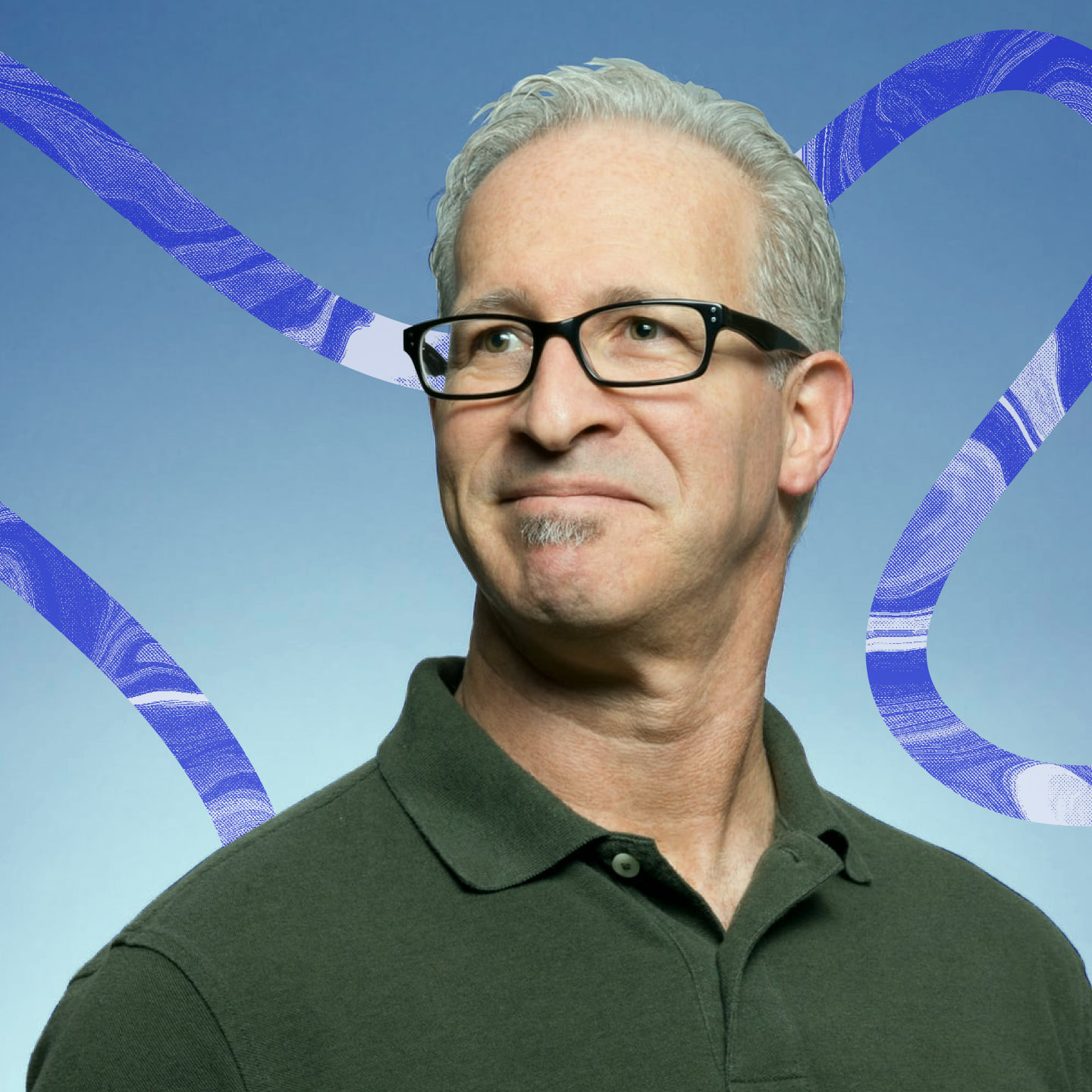

I'm a Cool Dad; It's Not That Cool

Growing up, I was asthmatic, poorly dressed, scared of girls and obsessed with Dungeons & Dragons at a time and a place where that was not in any way a social boost. Still, even the saddest social disaster has dreams of becoming less disastrous. It didn’t really happen in my teens (because of the scared of girls thing). Nor did it happen in early adulthood, as my artistic efforts of various sorts failed to impress anyone in particular. But even so, I thought my time was coming. If I couldn’t be a cool kid, or a cool young man, maybe, just maybe, I could come into my own as a cool dad.And I did! I am the cool dad. I am Crispin Glover at the end of Back to the Future, but cooler because that movie thought being rich is what makes you cool, and since we are not rich, we know that’s not true. There’s only one problem: Being a cool dad, it turns out, isn’t that cool. It’s kind of like being an uncool kid, in fact. You hang out over here, while over there someone has interesting parties to which you aren’t invited.

No doubt some (uncool!) parents will be shocked.

Being a Cool Parent Is Giving Your Child a Safe Space to Be Themself

My wife and I ended up as the cool parents via a few easy steps. First, though our house is tiny, our daughter’s room in the basement is large, so there is space to entertain. Second, we somehow, through the miracle of genetic recombination, created a daughter who is, in fact, cool and magnetic and beloved by her peers. All the cool queer kids (of which there are many) want to be wherever she is.Finally, and maybe most importantly, we’re very committed to allowing our daughter her own space and privacy. This practically means we’re not closely policing either romance or cannabis use. No doubt some (uncool!) parents will be shocked. (We can only speculate since we don’t hang out with uncool parents.) But in general, we figure that, especially for queer youth, encounters with the police are likely to be a lot more dangerous than encounters with a spliff. (My daughter was, in fact, the target of homophobic comments from police at least once.) It’s also easier to make sure everyone is vaccinated and tested if you’re holding a kickback at home than if you’re going out to bigger parties.Along the same lines, sexual activity is probably safer in your own space where you can prepare than if you’re forced into inconvenient nooks and crannies and automobiles. When my daughter has a guest or guests, they know they’re safe while they’re here, and they know that they can get a ride home from me in a pinch. It’s safe. It’s the home of the cool parents. That’s us!My daughter appreciates that her parents are cool. Her friends appreciate it too. Or so she tells us. We are dependent on her reports because we don’t have a lot of contact with her friends. Even when it’s just one or two guests, they don’t generally eat with us. Instead, my daughter surfaces like a skittish pizza badger, grabs the pizza and descends once more, amidst distant cries of “pizza!” We have been told the friends make much of the various fuzzy cats that visit. But again, this occurs out of sight, and the cats generally keep it to themselves, as cats will. There are a couple of cheerful, extroverted acquaintances who will chat at us if forced by circumstance. “Thank you for welcoming me to your home again!” one said with impressive courtesy. Then they were gone, not so much like a thief in the night as like a teen who doesn’t really want to talk to parents.

Maybe they were just making fun of me.

I Know Teens Don’t Want to Hang Out With Their Friends’ Parents

My daughter praised my musical taste when I was dropping a load of chattering punk musicians at various homes and public transport intersections after punk band practice. There was general acknowledgment that the Sinéad O’Connor album I was playing was OK. Maybe they all really liked the dad alternapop. Maybe they were just making fun of me. Maybe they were humoring my daughter because they like her. There’s no way to know because (again), they all pretty much avoid talking to me or my wife if at all possible. The cool kids didn’t talk to me when I was an uncool kid and—with the exception of my own daughter, who, just by virtue of proximity, can’t avoid me entirely—they don’t talk to me now that I’m a cool dad. This is not exactly the cool dad fate I had imagined. I had visions of chatting with the youth about—well, Sinéad O’Connor. Or The Green Knight. Or the state of contemporary theater. And I have, in fact, talked to the youth about those things. Very occasionally.For the most part, though, being a cool dad means specifically not forcing your child or their friends to deal with you. Parents have a lot of power in relation to young people. We’ve got the houses; we’ve got the cars; we’ve got the money and the ability to call in other, even scarier authority figures. If parents want to force kids to interact with them, they can. Parents can make kids eat at the table. They can search them for cannabis or alcohol or condoms. They can go down into the basement and stomp around and demand that you, and you, and you, pay attention to them for some period of time. And there are some parents who do all of those things.My wife and I try not to, though, because we are aware that teens don’t want to hang out with parents. They do not want to sit seriously in some sort of sitcom plot and listen to elders dispense wisdom. Instead, they just want a little space to call their own in which they can be left alone. I’m a cool dad because I don’t force anyone to interact with dad (cool or otherwise) unless and until they want to know where to find snacks in the kitchen or whether they can get a ride home. In the meantime, I sit in my room reading, much as I sat in my room reading when I was a teen. Now my wife is there with me, though. We roll our eyes together when the ambient noise from the guests spikes and wave at our daughter when she every so often checks in. Which is, admittedly, kind of cool.

I’m a Black Woman From an All-White Town; These Are My Memories

At a young age, I learned that sometimes the meanest remarks are made out of naivete.“Ouch! You poked me!”“I heard that Black people are that color because they’re dirty. I wanted to see if it was true.”My classmate knew that what she had done was wrong, somehow. She looked sheepishly at her fingertip, still clean and pink, and then back at me. We were eight, waiting for the gym class warm-up to start.“Oh, well, I showered yesterday…” I probably tittered nervously as I said it. It’s a habit everyone in my family shares. And then class started, and I never told anyone about the exchange.I grew up in a small town on the East Coast. It had less than 5,000 people, an "excellent school system” and a development that mixed cookie-cutter cul-de-sacs with 200-year-old farmhouses (sometimes with the farms still intact!). The town has great beauty. Driving down county roads, you can see rolling hills stretching out over the horizon dotted with trees and houses and fields. You understand why some folks stay there forever. Other times, driving down the same county roads, you come across a stop sign with a swastika spray-painted onto it. You understand why some folks are desperate to leave.

I was starting to realize that race does matter, actually.

I Struggled to Fit in as a Black Girl

At 25, I like to say I'm a New York City “seven” and a hometown “three.” It took me a long time to realize that attractiveness is not an objective quality.At 14, I started overhearing the boys in my class, who were all white but one, asking each other whether they liked blondes or brunettes. This was a little puzzling to me—are Black girls brunettes? My dad asked, a little harshly, why I cared what they liked. Was I trying to attract white boys? At 16, I looked in the mirror and generally liked what I saw. I wasn't "hot" (if you can even apply that word to a 16-year-old kid), but I thought I was cute! And I had a group of friends whom I loved and who loved me. I was having a good time going to football games and school dances, even if I overheard things I didn't like while I was there.“I can’t believe Melissa’s dating a Black guy. You know how they get at this age.”“On Friday, someone at Brett’s party called Rachel and her sister the N-word, so they left! I thought the two of them were being a little dramatic, honestly.”“Well, of course, she’s super good at track; she’s, like, the only Black person on the team.”By 17, I had a driver's license. My friends had driver's licenses and boyfriends or girlfriends with whom to drive around. Behind the wheel, I had a sneaking suspicion that I would never get a date in high school (I was right). I was starting to realize that race does matter, actually. Not just in a macroscopic, societal sense but very personally.

I Felt Like I Was Never Good Enough for Someone Else

When I was 18 and applying to college, my mom and I went away for a weekend to tour schools. I was one of five in my friend group who had never been kissed. That Saturday night in my hotel room, I looked through Snapchats from friends, dancing and drinking and getting up to general shenanigans at a party in someone's barn. “Wiggle” by Jason Derulo pumped in the background as they twerked across my phone screen."I hope I get to go to the next one," I thought as I drifted off to sleep. The next morning, I woke up to a text from my friend Liz. Four of the five remaining unkissed had paired off and made out with each other at the party. Obviously, I was devastated. I was the only Black girl in the group, and now I had the only virgin pair of lips. "Omg no way, congrats!" I texted them. "What the fuck, why doesn't anyone want to kiss me???" was the message I wanted to send. I was irritable and rude to my mom for the rest of the trip. Also, by now, I knew why no one wanted to kiss me. It was because I was “other,” strange, taboo—Black. Good enough for a friend, but not enough to be let into a family.

It was because I was 'other,' strange, taboo—Black.

My Hometown Never Gave Me the Confidence I Needed

I think I always understood that separation on some level, but it flashed into sharp relief during my senior year. I stopped thinking about who I could date or who might like me. I focused on platonic friendships, leaned into sports and hobbies that I liked, learned that I loved going to concerts. Basically, I found the contexts where the internalized racism of others had the least impact on their interactions with me. It was a great survival tactic.However, I see it was doable because soon, I would go to college in a city, and I hoped that there, I would get to date people who found me and my Blackness to be acceptable. I always say, "My town is a great place to grow up," and in the same breath, "Thank God I don't live there anymore."

More Than a Type: When Fetishization Becomes Racism

In the midst of the recent uptick in anti-Asian activity and otherwise harmful rhetoric as a result of COVID-19, I feel compelled to address yet another complicated layer to this unfortunate trend: gendered anti-Asian racism. Think you don’t know what that is? I bet you do. It’s Asian fetishism. For Asian women, dating apps are equally the most welcoming and the most oppressive spaces for us to exist. We get a lot of attention, but most of it is unwanted because it’s racially driven. Statistics have long shown that Asian women are highly favored in online dating, whereas Asian men fare much worse. I used to think I caught a lucky break being born as a woman versus a man, but I don’t anymore. Asian women and men face the same system of oppression but on opposite sides of the coin. For me, it's objectification; for men, it's de-objectification. For both of us, it’s stereotypes based on race. It’s an extremely complicated feeling knowing you are desired for something you’re born into, and for this attribute you’re also a magnet for hate. There is, indeed, a fine line between love and hate.Most people of color (POC) date knowing our race is a plus, minus or, at best, a consideration for any potential partner. White is the default in America. We are not that. Everyone has preferences that range from superficial to Socratic, but we have to acknowledge the tectonic shift that occurs when a preference turns into fetishization. Asian fetishization is often driven by expectations of deferential behavior, meek personalities and delicate physicalities—all stereotypes deeply rooted in imperialism, misogyny and other problematic systems. We need to stop accepting Asian fetishization as a type or preference and call it what it is: gendered, anti-Asian racism.

There is, indeed, a fine line between love and hate.

I Realized Racism Lived Within Me

Despite my awareness of this dynamic and all the ways in which it hurts me, I’m also painfully aware that racism lives within me. When I was hit with the realization that I operate under the same white supremacist and misogynist views as my nemesis (the White Man), it was devastating. We live in a society that centers on the white male experience, so it’s excruciatingly difficult to break free from that and find a new position—one that actually serves you, if you’re a woman or POC. In my late 20s, after a lot of therapy, it occurred to me that I exclusively dated blond-haired, blue-eyed, conventionally attractive white men because that’s who I wanted to be. And since my Asian hair and Asian eyes and overall Asian face betrayed me, I did the next best thing—I dated it. White supremacy has taught us all to revere whiteness and find close proximity to it in order to belong. We are trained to erase our own othering identities and strive to be as white-relatable as possible. For most of my life, I wouldn’t date Asian men and found ways to be as white as possible. That, my friends, is internalized racism. It’s crushing to come to terms with it. But do you know what’s more crushing? Realizing you live in a world that makes it impossible for you to escape racism, even if you manage to dispel as much of the internalized stuff as possible. I bet you know an Asian woman partnered with a white man. I’d also bet that Asian woman is attractive. White men decided that white men are the Übermensch, so once you cross a threshold of attractiveness, you gain access to the coveted white man. I bought into this for most of my life. I used to pride myself on seducing jocks who were typically interested in pretty blondes. I would joke I was a gateway drug or that I was colonizing the colonizer. On some level, I knew I was being oppressed and I wanted to flip the power.Eventually, it became clear the joking had to stop. I realized I was in a really hurtful situation, and that my desire to play with this power dynamic was only perpetuating a putrid and toxic ideology. I had to stop feeding into this narrative and start actively working against it. And since it was too enormous to change on my own, the most I could do was call it out, name it, speak truth to power.

I had gone on a series of dates with white men and discovered they all had Asian fetishes by the end of our first dates.

I Couldn't Escape Being An Object Of Fetishization

I can vividly recall the moment I realized the enormity of the problem. I had gone on a series of dates with white men and discovered they all had Asian fetishes by the end of our first dates. As a lifelong target of this particular type of racism, I can feel it in my gut when I am in its presence. But also, I’ve learned by now to just ask. I confront all men I suspect to be fetishizers with the question: “Do you have a preference for dating Asian women?” The answer, 100 percent of the time, takes some form of: “I like women with dark hair and almond-shaped eyes,” or, “I like that Asian women have smooth and hairless skin,” or, “You have a really strong work ethic,” or, “You age well.” I realize how unbelievable this sounds, but it is the horrid reality I live in. Naturally, I never react well to these answers, but when I point to the absurd racism of these convictions, I am either met with outrageous justifications or worse, defensive anger.After the fourth eerily similar experience in a row, I fell into a dark hole of confusion and despair. To be clear, this was probably my 40th experience like this throughout my life, but to experience so many in such rapid succession with men I thought I was purposefully selecting was deeply defeating.

I'm Rejecting The Commoditization Of My Existence

I made the intellectual decision to stop dating white men, simply because I know how hard it will be to find a white man who understands the systems that work against me well enough to relate to me in any real way. It’s not the fetishization, per se, but a basic lack of understanding of oppressive systems and racial inequity that creates a gap I’m not willing to bridge. But here’s what’s messed up. You’ve probably noticed that I’ve only mentioned dating white men. That’s because I have historically been more attracted to white men. I’ve come a long way from only dating Tim Riggins, but I still have a strong attraction to white men that I can’t shake. And I can’t decide if I need to shake it. I realize I am a product of my society, but I know too much to just accept the way things are. Essentially, I’m stuck in a literal no man’s land where my body wants a white man but my brain doesn’t. I guess the only place to go from here is a lonely and decrepit life with my dog. But the fact remains that I am wholly uninterested in dating someone who commodifies my race, and therefore my existence.

The Pressure of Black Excellence Was Bad for My Mental Health

I was so good at being the best.In class, in extracurriculars, and even in my friendships, I always did more than was necessary, and reveled in the fruits of my labor: high grades, incessant high praise and the admiration of my peers. But none of this was for its own sake. Each extra mile I went made me feel a little closer to earning my right to be there as a Black girl in a predominantly white institution.All my life, I have attended prestigious, white institutions, and all my life I have excelled in them. Racking up accolades for academic achievement, leadership positions and clubs, I did everything right. But all of my moves were practiced and intentional. Both the dopamine hits of approval and the sweet anticipation of working hard to taste the fruits of my labor felt like an adrenaline rush I was in the middle of all the time.Looking back, this was neither anticipation nor adrenaline. It was anxiety.

I carried that burden for years, making all the right moves.

To Me, Black Excellence Wasn’t a Choice; It Was Expected

I was always restless. Inactivity felt like a cardinal sin; rest was out of the question. Any time not spent chasing excellence was wasted, and I didn’t want to prove that the assumptions people made about me—that I was there to fill a quota, that I was less qualified and less sophisticated than they were—might be accurate.And it wasn’t all in the pursuit of vanity—it felt like my responsibility. I had heard it all my life: a chorus of voices telling me how proud I was making everyone, what a good example I was. My success was the success of my family, my extended family and my community—it takes a village, after all. They saw themselves in me, and saw my success as their own. My excellence disproved their own self-doubt, too, and reassured them that their internalized notions about Blackness and their own worth were wrong.So, having been raised with the weight of my “potential” impressed upon me, it was a given that the consequences for not living up to it would not be personal, but dire for the whole community. I carried that burden for years, making all the right moves, getting into all the right schools, reading all the right books and talking with the best of them. “Don’t waste it,” everyone told me, and that propelled me higher and higher up the social hierarchy, fueling my adrenaline and anxiety with each rung.

No Matter What I Achieved, It Never Felt Like It Was Enough

Yet, as I forayed further inside these circles, they became more complex. I acclimated to the correct cadences, I learned to recognize status symbols and tried to acquire the few I could. Yet the more I tried, the further away I seemed.There was always something more to be gained, I finally realized—some other mantle to reach. Even if I got the highest grades, people saw me as a scholarship case. Even if I wore the right clothes, carried the Longchamp bag and bought the Moncler coat, the status symbols were wasted on me. At work, people were surprised by my eloquence but still underestimated my ability. I felt like an imposter and no one was mistaking me for one of them. For all my trying, and even my successful attempts, I felt like I was playing a game of catch-up, hoping to reap some vague rewards of outward approval. The dissonance between my home community’s perception of my success and the fraud I saw in myself only deepened my imposter syndrome. Suddenly, I felt different than the people at home, and was othered by the people at school. My isolation meant I had no one to turn to, and the fear of disappointing the people who had supported me and nurtured my potential made me feel stuck, hopeless.So I kept climbing the ladder. I got into a good college. I spent the summers doing prestigious internships where I was, again, almost always the only Black person, or one of very few. By all accounts, this was making it. I tried to feel satisfied by my achievements but they never felt tangible, as though resting on my laurels, even for a second, would break them. My place in these privileged spaces always felt precarious, and my paranoia was taking its toll. Afraid to be exposed for the fraud I still felt I was, I worked and worked and worked in an attempt to prove myself.Until I burned out.It was inevitable, my burnout, and with it my disillusionment of the systems I had been taught to revere. Why was I working myself to exhaustion when no matter how hard I tried, I was still just the Black girl? And why was I so desperate for the approval of a system I knew was rigged?

The Problem With the Black Excellence Movement

The 1:1 value I had placed on my self-worth and production output was a direct function of the capitalist system I know to be flawed and embroiled in white supremacy. Basing my value on my acceptance by elite institutions, from boarding schools, to private colleges, to prestigious companies, was not really validating my community, but validating the hierarchies that oppressed my community. All my work had not been in service of myself, but in service of the institutions which had succeeded in making me feel like I was inherently “less than”—the very function of racism.In an embodied way, I had given myself to racist institutions in the name of progress and being a credit to my community and my race. And this outdated lie that Black excellence is defined by success in established systems is perpetuated relentlessly. From news highlights on “first Black” milestones, to award shows and the entertainment industry, giving Black artists tiny morsels of recognition while exploiting their output and aesthetics for monetary gain, we’re taught to appreciate these moments of recognition and hunger for them as I had.However, my experience within the upper echelons—befriending the children of dukes and billionaires, working for internationally recognized names and institutions—proved that there was no space for me there. Marginalized groups are always going to be othered by elite institutions, which were built to advance the white heteropatriarchy and continue to oppress and gatekeep other communities. My place there had only served as an example of adherence, that if one were to work within the system, they would be rewarded.

I quickly realized that I was working at the expense of my community.

Rejecting Black Excellence and Embracing My Mental Health

But after I realized I was working fruitlessly at the expense of my mental health, I quickly realized that I was working at the expense of my community, too. To be a credit to our race is to resist the notion that we need to prove our worth measured against whiteness. To advance my community is to dismantle the systems that I was embroiled in. Learning to reject the narrative I had been taught took years of self-doubt, isolation and tireless, thankless work. Finally, through introspection about my values, I realized that the excellence I was striving for was actually leading me away from Black liberation and activism, and further inside the broken system at the expense of my mental health. So many of us are stuck in this cycle but it's time we get out. It may have taken burnout and breakdown for me to get here, but I’m glad I did.Now I am learning not to look for approval in my work, my output, my purported “success.” I find fulfillment in engaging in my community in a meaningful way, and reading, working and organizing towards liberation.

Black Lives Still Matter When the News Cycle Ends: Where Does BLM Go From Here?

Growing up, I spent a lot of time learning about activism and Black Lives Matter, but nothing that I experienced compared to the explosion of protests around the world following the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. I could barely open social media without being forced to relive the realities of many Black people around the world—during the ongoing deadly pandemic. It was harder for people who aren’t Black to turn away from these injustices too. Everyone was suddenly getting with the times—dare I say woke—even though it may not have been an authentic stance against police brutality and anti-Blackness, but a personal pat on the back that called for others to view them as an agent of change.

Truth is, the plights that Black people face haven’t changed, nor have they been dismantled.

Was Corporate Support for Black Lives Matter Just Pseudo-Activism?

“Pseudo-activism” is when groups show support for a movement or set of beliefs solely because everyone around them is doing so—and not because they actually believe in the message behind the cause. Rather quickly, I noticed that the influx of support for Black Lives Matter was the latest bandwagon that brands were jumping on. The type of violence that Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and countless other Black people have experienced is nothing new, and I felt conflicted seeing the sudden support. On one hand, it was amazing to see so many companies that I’d supported throughout the years releasing statements, but I could never seem to silence that voice in the back of my head that kept asking: What took you so long? Why now? What was so significant about this year that was different from 2012, when Trayvon Martin was murdered?What I realized is that while many conversations held in 2020 may have been about Black people, we weren’t always the target audience. The public statements that we saw a lot of large companies releasing suggested that after years of silence, they were suddenly deciding to take a stand against anti-Black racism, but they didn’t feel sincere to me. From Microsoft to Adidas, I spent a lot of time reviewing the PR-proofed missives companies released, but what spoke volumes to me was the fact that while these brands were pledging their support for the advancement of Black people and against police brutality, there was a noticeable lack of Black people in positions of power at these same companies—including ones that I’d worked for myself.It was easy for companies to draft a letter to avoid looking like a company that had stayed silent during a revolution. But many of them failed to acknowledge the anti-Blackness at work in their hiring practices, daily operations and the pay inequalities that exist between Black employees and their white counterparts.

When It Comes to Supporting Black Lives, Actions Speak Louder Than Words

Seeing the problems that other companies have had with diversity is sad, but what impacted me more was being employed by a company that made a statement internally, while also having white employees that were being paid higher salaries than me for the same work. Or seeing white coworkers whose salaries weren’t impacted during the coronavirus pandemic, despite company-wide emails suggesting that all employees had received a reduction. Their performative support hit so close that it crushed my spirit and made me question my career. When you’ve worked hard to be a champion for a company while witnessing the devaluing of Black lives daily, it feels like a slap in the face when you have to carry on as if nothing is happening.It quickly became clear that companies deciding to speak out or stay silent was more about them than it was about me—and once the news cycle moved on from speaking about Black Lives Matter, the social media campaigns from large companies stopped. Black people are still experiencing the same oppression, but the commitment to dismantle anti-Black racism where it exists seems to have been put on the back burner.

We need those in positions of power and privilege to do the work as if their lives depended on it. Because my life does.

It's Easy to Support Protests, but It's the Hard Work After That Matters

Truth is, the plights that Black people face haven’t changed, nor have they been dismantled. Following the protests that erupted in 2014 after the murder of Michael Brown, six prominent activists involved with them mysteriously died, and police ruled that none of their deaths were suspicious. KJ Brooks has detailed how, after she went viral last year for a video holding members of the Kansas City Police Department accountable, the KCPD followed her to the point that she had to hire a private security team. Despite the patterns that take place before our eyes, Black people can’t get the support we need when our lives are in danger, when an act of violence can be prevented. The attention usually only comes once another life has been lost. It’s terrifying, and I wouldn’t wish these experiences on my worst enemy. When we hold white supremacy accountable, our lives are at risk. When we ignore it, our lives are still at risk.Companies committing to challenging anti-Black racism and police brutality isn’t a one-time deal. We need those in positions of power and privilege to do the work as if their lives depended on it. Because my life does, and it’s not the responsibility of those who are oppressed to get rid of oppression that we didn’t create. I hope that the companies that released statements last summer do right by their sentiments, and put in the necessary work within their companies as well as the community. It’s possible. It will take a lot of work, but that’s the point. Committing to change because everyone else is doesn’t solve the problem—it simply delays solutions from taking place. If you are going to stand for Black lives, remember to do the work when the cameras stop rolling and the world is no longer watching.

This Is What It's Like to Be a White-Passing Person of Color

When I was six, my best friend asked me why I was white when my dad was Black. I laughed and told her that he wasn’t Black, he was brown. She looked at me like I was a fool and said, “Aren’t all Black people technically brown?” And thus began my practical education on racial identity in America.The truth is, no one wants to hear about racial experience from someone who looks like me. And that’s fair. To think that a society built on the persecution of Black and brown people needs more think pieces about whiteness is utterly tone-deaf. So this is not an essay on whiteness. It is a story of what happens when identity and loss collide, and how the collective identity of a family shapes its individual members. I am the child of a Muslim immigrant from Pakistan and a white Irish Catholic lady from New Jersey. There is a trickiness to the language Americans use to talk about race, one that leaves no room for my existence. There’s the Black-and-white binary, as well as the amorphous “person of color” designation given to those with more than strictly European lineage, whether or not they have African ancestry. By this logic, I fall into the catchall category of “people of color.” But I am not a person of color; I am a genetic fuck-up that defies all principles of inherited traits. Rather than an even blend of my parents, I came out as white as my mother—pale as a ghost, blue-eyed and so blonde I looked bald. My eyes and hair darkened with age, but my skin stayed translucent, with my constellations of freckles as the only trace of melanin. So I cannot be a person of color, because by definition whiteness is the absence of color. A white person of color is an oxymoron.

Thus began my practical education on racial identity in America.

What’s the Difference Between “White-Passing” and “White”?

I don’t remember the first time I heard the phrase “white-passing,” but I should, because it changed everything for me. I wasn’t “white” anymore, I was “white-passing.” A white-passing person of color. Finally, I had a way of describing myself that separated me from my white peers, without encroaching on the space of real people of color. Or so I thought. Calling myself a white-passing person of color worked because, for the most part, there weren’t any Black or brown people around me besides my family. Leaving my predominately white suburban hometown for the diversity of a liberal arts campus gave me a much-needed reality check. The first time a Black student corrected me, emphasizing that to call myself a person of color was inauthentic, and the “white-passing” qualifier was useless, I cried. Then I felt like an idiot for crying over such a coveted, life-saving privilege. I looked in the mirror and saw myself for what I was, the epitome of white fragility, insisting on my brownness the same way whites accused of racism insist, “But I have Black friends!” There is no practical difference between being white and white-passing. If an employer sees me as white, if a loan officer sees me as white, if a cop sees me as white, if any person who does not know me intimately sees me as white, then I am white. If I enjoy all the perks of white privilege and suffer none of the consequences of being brown or Black in America, there is no question, I am white. Racial identity comes not from your blood, but from how others see you. Deep down I knew this. I even accepted it. But then came Rachel Dolezal. In our class discussions about her infamous racial fraud, I was shocked to find my experience compared to hers. Most of my classmates agreed, a self-proclaimed “white-passing person of color” was no different than a white woman pretending to be Black. And was it? I asked myself over and over, what was the difference between Rachel Dolezal and me? Were we both just white women desperately clinging to some sick fantasy of otherness? I was telling the truth, but what did it matter? Why did I have such a visceral reaction to being called white, when I am clearly white?

Even Within My Family, Our Racial Identity Was Complicated

I’ve spent the better part of my years since college trying to answer these questions. And as far as I can figure, it comes down to two things. It breaks my heart to never be seen as my father’s daughter, and it frustrates the hell out of me that, as a “white” person, people assume I only have the experiences of a white person from an all-white family. My young friend was the first person I remember that questioned my relation to my father, but she certainly wasn’t the last. While my two brothers’ skin would effortlessly darken in the summer sun, I would look on with envy, freckled and burned. Strangers, family and friends alike gushed at how my little brother was the spitting image of my father, marveled at how my adopted older brother could easily have passed as our father’s biological son, and then would look at me, smile sadly, and remark that I, of course, was my mother’s daughter. I could take the constant questioning when my father was there to reassure me. When I looked closely at our family photos, I could see we shared the same crooked smile, round face and high cheekbones. I clung to these family portraits as irrefutable proof that I was, despite the color of my skin, half Pakistani. But many years before I looked like the woman I am now, my father, the only unimpeachable tie to my Pakistani heritage, died.

Losing My Father Meant Losing My Heritage

So when I am called white, even by myself, it effectively severs the connection to my beloved father that I have fought time and memory to preserve. Loss and identity are tangled together for me, and you cannot question one without exhuming the other. This is why discussions about my identity make me so emotional. Every time I’m assumed to be white, I’m 11 years old again, sobbing uncontrollably over my father’s body. Losing my father made our whole family whiter. Without our dad standing next to him, my little brother started to pass. In the winter his skin gets almost as white as mine, and though his face is unmistakably my father’s, without him around for reference, no one could see it. People who came into our life who had never met my dad started to remark how much my brother looked like our mom. Our older brother immediately stood out now as the darkest member of our family, leaving no question that he was adopted. We didn’t see our Pakistani family as much. We never ate Pakistani food because it upset my mom’s stomach. We didn’t go to the mosque or celebrate Eid or listen to Punjabi music anymore. None of us learned to speak Urdu. My mom got remarried to a fellow white Irish Catholic, and just like that, all visible traces of Pakistan disappeared from our family.We had traditional biblical Anglo-Saxon names. All of my cousins, even the ones that were half-white like me, had names from the Quran. They spoke Urdu and made yearly trips to Pakistan. They had been bullied in school after 9/11, despite sharing my skin tone. Culturally, they were Pakistani and therefore could not pass. But who is to say we would not also have grown up with Pakistani culture if my father had lived? Would I be less passable—less white—if he was still alive? Would I speak Urdu with a native tongue and make samosas every week? Would I drape myself in my grandmother’s saris for special occasions? Would I have seen the country that my family lived in for centuries? Would I, in spite of my mother’s skin, be accepted as a person of color if I lived and acted less American and more Pakistani? Probably not, but I will continue to wonder for the rest of my life what my relationship to my identity would be like if it wasn’t cocooned in grief.

When I am called white, even by myself, it effectively severs the connection to my beloved father that I have fought time and memory to preserve.

My Mixed-Race Family Has Made Me a Witness to Racial Violence

The second reason I can’t seem to be satisfied with condensing my ethnicity to just “white” is that I have experienced things that fully white people never could. While white privilege renders the difference between white and white-passing individuals nonexistent, the differences between growing up in a white family and growing up in a mixed family are enormous. Being white-passing from a mixed family may not change the way the world sees you, but it absolutely changes the way you see the world. A white person from an all-white family would not have seen her six-year-old brother held at gunpoint by a cop. A white person from an all-white family wouldn’t know firsthand that the “random” extra security checks at the airport are not random but rather triggered by Muslim surnames. A white person from an all-white family would not have to explain to a police officer that the man she is with is actually her dad, and not an abductor. A white person from an all-white family wouldn’t flinch hearing the things white people say when there are no brown or Black people nearby. A white person from an all-white family would not fear the violent shockwaves of Islamophobia following 9/11 or Trump’s Muslim ban. In no way do I mean to suggest that these experiences took the same toll on me as they did on my brothers and father. But how is it possible to carry so much racial trauma and remain unaffected, even if you are just a witness? While there is no need for the term “white-passing” when describing an individual, I think it, or something like it, is necessary in the context of a mixed family. To be seen as white and only white is not only to lose my father all over again, not only to whitewash my DNA, but to dismiss all the hard-earned truth about race in America that I have gathered over a lifetime of watching loved ones be persecuted. My ethnicity, therefore, cannot be a one-word answer. There is no verbal shortcut that adequately sums up my heritage. I live in the liminal realm of both and neither. I am half-Pakistani and half-Irish, and I refuse to compromise either. I won’t pick a side, even if the world has picked one for me.

Growing Up Muslim in a Post-9/11 America: What It Was Like

The day of Eid al-Fitr is one of the most exciting holidays for a young Muslim kid. You’re showered with money and gifts by family and friends. What more can you ask for? But at the age of six, on the morning of Eid in 2002, my father was arrested by the FBI, accused of being a terrorist. The day was all a blur to me. I can only remember crying and being confused. It wasn’t until last year that I found out what really happened that day. The FBI Joint Terrorist Task Forces (JTTF) had taken him to jail. I have slight memories of my mother telling me my father would be gone for a month to go on “business trips.” I also remember sitting in the courthouse waiting rooms for hours wondering what was going on. Now that I’m older, I understand why my mother kept this away from us: It would’ve been traumatizing for me and my sister to know that the JTTF tortured our family with constant surveillance over a six-year legal battle. After finding no evidence, the judge finally acquitted him of all charges and stated that he had done no wrong. By speaking his mind, he was simply exercising his First Amendment right.

Why Growing Up Muslim in America Is Difficult

Growing up in Los Angeles has been a unique experience. My father is Arabic and my mother is Hispanic. I was lucky enough to be raised with two very different realities: My mother was more open-minded whereas my father was a bit stricter, especially when it came to religion. Before my parents married, one of the things they agreed on was that their children would be raised Muslim and carry Muslim names. Until this day, people have trouble pronouncing my name, Ibrahim. I’ve heard it all, just one of those annoying things growing up. Sometimes, it would take teachers weeks to finally get my name right. Substitutes were particularly creative with my name and at times made me the laughingstock of the class. Today, most of my friends call me Ibra, which is much easier to pronounce.When I turned ten, I struggled with fasting the month of Ramadan. In most Muslim countries, kids start fasting at the age of five or six, which I find a little crazy. I guess it’s doable when you live in a society where the entire population is participating in the ritual—community does matter.In the U.S., I grew up with people from all types of religions, and at ten years old, seeing other people eat and drink during the day was extremely difficult. At times, when I was out of my house, I was tempted to break my fast. After all, no one cared or was watching over me during school. I’ll admit, I did sneak in a few sips of water here and there “accidentally.” Oops, I was supposed to rinse and spit. As I got older, I began to be much more committed to the ritual and understood the importance of being true to my commitments. I also came to love the sensation of taking in my first bite of food and sip of water at sunset.

You don’t have to be religious to be a good person.

Figuring Out How to Be Muslim in America Was Especially Challenging

I can still hear my father’s voice in my head: “Allah is always watching.” At times, this voice filled me with fear and at others, it seemed to energize me. I grew up practicing Muslim principles. I read the Quran and attended Sunday school like every good Muslim kid. Islam was a huge part of my identity growing up and it molded me into the person I am today. One can say my father was very strict and imposed the religion on me. At the end of the day, when you get older, you make your own decisions—I still practice Islam but am not as religious as I once was. I do believe in Islam and that being a good person is most important, too. You don’t have to be religious to be a good person. This is where my mother’s influence comes into play.I had a lot of questions growing up because I was an Arab Muslim, an Ecuadorian; and my mother is Catholic. She isn’t very religious, but she raised me to be kind and gentle and to always be compassionate and caring. Most of my mother’s side of the family resides in Los Angeles, and I grew up with many cousins who weren’t Muslim. They never understood why I would fast, and wouldn’t eat pork. They would jokingly try to entice me to try bacon, but I never did. My father and other Muslims consider pork as the most unclean animal, connected to disease, and this teaching always remained firm in my mind. Years passed, and my mother’s side of the family no longer serves food at any of our family gatherings. I guess our Muslim ways had a positive impact on that side of the family.

Being Muslim in America After 9/11 Was Even More Challenging

I remember being on the receiving end of racism because of my ancestry. I recall being referred to as a “beaner.” In L.A., if you are Hispanic, people will automatically assume you’re Mexican, using the word as a form of insult. Sometimes, I felt unsafe to reveal that I am Arab and Muslim, and it occasionally felt safer to say I was Hispanic. It was a blessing to have the choice. If I said I was Hispanic, people would automatically assume I was Catholic. I felt judged and sometimes criminalized by people—sometimes at first glance. After 9/11, it was difficult for Muslim Americans, even in metropolitan cities like L.A. Being born in American is not a reason for people to expect me to erase my roots or feel shame because of my ancestry.During Eid or Ramadan, I would go to the mosque wearing my dishdasha, a long traditional white dress that men wear in the Middle East. My traditional gown brought me much attention from people outside of my community. People would look at me in a way that I felt their fear and discomfort. Their expressive look made me feel unsafe. The one place I always did feel safe was at the mosque surrounded by my community. In high school, during our yearly international fair, I would attend wearing my dishdasha. I could hear people whispering “terrorist” under their breaths. At times these comments felt hurtful and brought up the question, “Do I belong?” I grew out of the need to react to ignorant comments and began to fully embrace my culture and religion.

After 9/11, it was difficult for Muslim Americans.

America Isn’t the Only Place Where Muslims Are Misunderstood

I began to understand how society portraits Muslims. It’s not just the U.S. that targets Muslims. The world news in practice paints Muslims as synonymous with terrorism. They taint the Islam community based on the activity of extremists that represent less than one percent of the Muslim population. They have done a great job at giving me and my culture a bad reputation. The scary images and stories delivered through the news propagate hatred that triggers tragedies like the 2019 mass shootings at the mosques in New Zealand. Can you imagine the kind of ugliness that fills these attacker’s minds?As a young Muslim adult, I realized ignorance and racism put my father in jail, but the First Amendment set him free. I see that my generation is open-minded and accepting of others. Will Israel and Palestine ever come to a settlement? I don’t know. Can Muslims and Jews live in harmony? Yes. Some of my best friends are Jewish and we will remain friends until the day we die. Our religions unite us in many ways. There is hope. If I, an Arab Hispanic Muslim, can be friends with everyone, so can you.

I Ignore Racism Today; You Should Too

The topic du jour that seems to riddle every politician’s social media feed, blast across newspaper headlines and take up an uncanny amount of time in campus classroom discussions across the U.S. is racism. And, as an African woman with little time for frivolities, allow me to just comment by saying: Quite frankly, I am sick of it.Permit me to be candid: I get it. As a first-generation American whose parents are African, I understand that racism is real and, oftentimes, impacts people profoundly in the United States. I know the history.I am not denying that racism exists—there will always be unscrupulous people who care more about the color of my skin, and the religious convictions of my choice, than who I am as a person. And, of course, I have witnessed racism firsthand. I wear a hijab; I would be remiss to not admit that I have, many times, been looked at with a sideways glance. I have experienced random stares, smears and vulgarities based exclusively on my race and ethnicity. That—the behaviors of others—I have absolutely zero control over.What do I have one-hundred percent control over? Easy. I can control how I react and how I choose to respond—or not respond—to random racist comments or innuendos hurled in my direction. How do I respond? Simple. I don’t pay them one bit of attention.

Racism Stops with Me

Of course, if racism was—as some people like to portray it to be—an ongoing, never-ending reality, I might not be as eager to shrug my shoulders and walk away from the casual slights. But, simply put: It is not.Out of the 10,000-plus interactions I have with people every year, maybe four of them—at most—are marginally uncomfortable, smelling of a minor hint of racism. The other communications are pleasant, amicable and seem to have nothing whatsoever to do with my race or ethnicity.The four that are slightly uncomfortable are not worthy of my time nor even one small shred my energy.A note for all of the “heroic” people out there, who think it is helpful for you to valiantly come to my defense like a white knight riding his noble stallion into battle: Save it for someone else. Even though I know that the people who stand up for me and jump to my defense sincerely have wonderful intentions, their actions are mutually exclusive to my desired outcome. What I want is to ignore the racism, and, how can I accomplish this goal when people are making mountains out of molehills?

Quite frankly, I am sick of it.

Ignoring Racism Is My Way of Fighting It

The next logical question that springs to mind is: Why do I not want to pay attention to these racist scoundrels? I don’t want to pay them a bit of heed because, ultimately, they do not matter and neither do their words or actions. Instead, I want to deprive racists of my time and energy for two primary reasons. First, I earnestly feel that if I give them attention, then they have won.Ask yourself: What do racists want more than anything? The answer quickly becomes apparent: They want attention. They want to get a rise out of me; they want to make me mad. Therefore, if I give them the attention that they are blatantly seeking, then I have allowed them to win. My second reason for not wanting to waste one minute of my time on them is that, at the end of the day, I simply choose not to be offended. If I show them, repeatedly, that I am indifferent to their slights and rude comments, then I hope that they will come to realize that I am not fundamentally different from them. I hope that I will be viewed, eventually, as just one of the masses in just a different shade of skin tone—which is precisely the outcome I seek.

I am not denying that racism exists.

Fighting Discrimination Sometimes Hurts More Than Helps

Perhaps an example might be more poignant and revealing. A couple of weeks ago, I decided to treat myself to an exquisite meal at a swanky, multi-Michelin star restaurant. No sooner am I seated than the waitress comes up to me and asks me to pay for my food before I order. While taken aback slightly, I do not miss a beat. I simply pull out my credit card and, in a polite voice, graciously offer it to her. Problem solved, right? Not so fast. From somewhere behind me leaps to my rescue a social justice warrior, ready to come to my defense as if I had just been hit by a bolt of lightning. She abandons her first course of food and decides to begin yelling at my waitress for having the audacity of making me pay before I ordered. My waitress, still not backing down, simply said that it was company policy to do pre-pays randomly—that it was just a part of the normal protocol. Now, we all knew this was a big, fat, blatant lie.Of course, the restaurant does not ask white businessmen in thousand-dollar suits to prepay for their food. We all know that the whole thing is happening because of my race. Yet, instead of adding fuel to the fire, I jump to the waitress’ defense and kindly ask the social justice warrior to not get involved. Rather than honoring my request and going back to her meal, she boldly proclaims how it is her fundamental duty to say something when she sees a grave injustice transpiring. She loudly insists that the manager comes out to explain this atrocity. The scene continues and, before any of us know what has happened, we are both standing outside of the restaurant wondering what the hell just happened. Hands on our hips, we are both pissed. She is angry because she has witnessed secondhand discrimination, and I am livid that my meal—which might I add, I had waited a month to enjoy—has been snatched from me. Who won this battle? Certainly not me.What she doesn’t get is that she and her fellow warriors are undermining my fight. They are making it harder for racial minorities to move along and become a member of society. And what these people refuse to understand is that the overwhelming majority of us do not care. We don’t! And, believe me, it is not because we are so tired of constantly fighting and being on edge. We don’t care because racist people and events are few and far between. They do not matter.They are equivalent to the dinosaurs, in my book, and are basically a dying breed who are trying like hell to live on in a world that no longer is habitable for them. The proverbial meteorite has already hit, and it is just a matter of time before the last of them breathes its last breath. (If fellow Americans only knew true racism and conditions in parts of Africa like where my parents are from, they might calm down about a weird glance.)

A note for all of the 'heroic' people out there, who think it is helpful for you to valiantly come to my defense like a white knight riding his noble stallion into battle: Save it for someone else.

Human Nature Is Misconstrued As Modern-Day Discrimination

I am also constantly hearing people say things like it is racist when white people want to live among other white people in similar neighborhoods. Or how people who only date a particular race are racist. Look, here is the reality of life: People like their own cultures and want to be around their own people. People feel most comfortable when they live, work and interact with people with whom they have something in common. That isn’t racism: That is human nature.No one calls me a racist when I want to live in cities and neighborhoods with fellow Middle Easterners. Instead, such places are lauded as greater preservers of culture and unique oases in the middle of crowded cities. So, why are predominantly white neighborhoods looked at any differently?In my humble opinion, this is not racism, this is just human nature. Cultural attraction—being attracted to someone from the same culture as you are—is real and needs to be recognized as such. It does not make someone a racist. It makes someone human.Social justice warriors and anyone else who wants to see racism lurking at every turn and hiding in every corner: Please, consider what you are doing and the message you are sending when you jump to our rescue and push your agenda—which is not control necessarily our agenda—on others. Racism is dying, and we shouldn’t give it even a speck of attention or fuel the flames of its existence. Instead, ignore it, live your life and allow minorities to live theirs. Racism will be gone in a generation or two, and, in the meantime, let’s just enjoy this rodeo they call life.

I'm Neither Black Nor White: Why I Embrace the Latte

I was proudly wearing my Lynyrd Skynyrd t-shirt when I was stopped getting off the bus by an older white male. He was amazed that a teenager who looks like me even knew who Lynyrd Skynyrd was. Sorry mate, musical tastes aren’t defined by how brown I am.I’m not Black. Neither am I white. However, for reasons that I suspect have a lot to do with my upbringing, my personal history and our society, being told I’m white doesn’t enrage me as much as being told I’m Black.I was born to a Black father and a white mother, and I grew up squarely in the middle. With my “latte” skin, I was praised on one side for my lighter tone, and on the other for my sun-kissed complexion. I sometimes, as a child, wonder why I wasn’t just one color. But otherwise, I experienced racism like any child would: with incomprehension and dismay.

Skin Color and Culture Aren’t the Same Thing—Even Though People Think They Are

I spent my formative years fluctuating between two colors and two cultures. And then, without any real conscious decision on my part, I wound up very much on one side. As a Jamaican friend pointed out when I was in my early 20s, I’m “so white.” Everything that defined me—except my skin color—planted me firmly in the white camp. To align with one culture or another, we have to understand them. Society would have us believe that “white culture” is mainstream culture. “Black culture,” on the other hand, is defined by subcultures predominantly adhered to by members of society with a certain melanin level. As Justin Simien, director of the 2014 movie Dear White People, explained in an op-ed for CNN, Black culture “is what people assume about [B]lack people and how they should sound, live and act.” To be Black, one has to do this and like that, as if one’s skin had anything to do with matters of taste. One’s skin is, of course, really what it comes down to, but this is not the only thing that defines “Blackness,” at least not in the sociological sense. Cultural Blackness has very little to do with how Black someone is, but our society’s obsession with differences would have us believe it is one and the same thing.

I experienced racism like any child would: with incomprehension and dismay.

Am I Black or Not?

As a mixed-race woman, where I stand in this division of culture gets somewhat complicated. My genes are all tangled, and I could, technically, be said to be Black—or not.From my art university background to my obsession with travel, from my love of classic rock to my very real addiction to cappuccinos, my Jamaican friend could not fathom anyone mistaking me for a Black woman. To her, everything about me screamed “white.”And she might be right. In the years since her comment, my inability to be “Black,” inasmuch as what society would associate with Black culture, has only been exacerbated. Of course, I rebel against any idea that melanin levels influence one’s tastes and cultural associations. Our societal need to put people in neat, easily-understood little boxes isn’t going anywhere, leaving me stranded here, not white, but in the white box nonetheless.How does one navigate the Black/white divisions our society’s normalized when one’s identity is both everything and nothing, Black and white? Every Black-bashing comment around me is accompanied by a look in my direction that makes me want to shrug, even as I laugh and get exasperated at the white clichés casually peppered all over the internet.We can all (hopefully) agree that racism is bad, but what particularly annoys me isn’t racism as such. Every attempt by people to put me in a “category” makes my skin crawl. This would be understandable if being put in any category got the same reaction. Interestingly, it doesn’t.I have come to realize that racism shocks me for all the “wrong” reasons. Raised by my white, European mother, everyday racism jars my sense of whiteness. A joke about “the Black people over there” when I sit next to a Black friend at the pub makes me look around and frown. “Are they talking about me?”White people’s view of me clashes with how I see myself. This is something that becomes apparent every time I’m in the U.S. or when I meet Americans. Every single time, the question of “where are you from?” comes up and every single time, my answer is found to be wanting. “But what are your origins?” This question, interestingly, is never asked by Europeans—we seem to understand that you can be a Black and French, or of Asian descent and British. Telling them that I’m from my city never brings up follow-up questions.

For Mixed-Race People, Is Racial Identity a Choice?

Identity is a complicated concept, and self-identification has made headlines for a while now. Gender and sexual identity are one thing, but when it comes to race and culture, can you “choose” how you self-identify?As someone who is truly on the fence, in racial terms, if I can claim whiteness, can I also switch and claim Blackness? Can I say the N-word? Can I—should I?—be annoyed at racism directed towards me, even if it is mainly because it makes me want to scream, “I’m not actually Black you idiot!”Racism is unacceptable, both white and Black people will happily tell you. What I’ve come to see as “one-colored” people will then proceed to regurgitate whatever clichés they have about “the others,” safe in the knowledge they are squarely on one side of the argument, and no doubt about it.Clichés color my own reactions too. Being called Black is associated with negative feelings. The angry, loud Black woman, but probably more importantly my father, a man I have not seen in 15 years. My relationship—or lack thereof—with my dad has absolutely nothing to do with his skin color, but associations are created whether they’re rational or not. Being called Black is calling me my father’s daughter, and that will not do.

And then someone makes a comment and I cringe.

I’m Happy as an Outsider

As neither Black nor white, I should not have to choose a camp—and most of the time, I don’t. I don’t spend any time whatsoever anymore wondering whether I’m one or the other. And then someone makes a comment and I cringe.Ultimately, I really am neither, a position that I relish. As an outsider, I enjoy being annoyed at every excuse for racism that brings up colonization and slavery, at every “victim posturing” and displacement of responsibility. This is almost as liberating as being able to climb on my high horse and look down at every self-centered comment, Eurocentric rewriting of history, complete lack of awareness of what it means to be “other” and tone-deaf defense of this or that privilege. “We went to the Bronx and OMG! I was the only white person there! So uncomfortable,” a fellow traveler recounted to me recently after a trip to New York. I have never laughed so hard. And so, I roll my eyes left, right and center. I refuse to be called Black, but when I think about it, I don’t particularly want to be called white either. White people see me as Black, and Black people see me as white. Which would tend to mean I’m Black, while thinking of myself, mainly, as white. Or the reality is somewhat simpler: I am neither.

Racism in Theater Is Real: My Journey as a Black Actor