The Doe’s Latest Stories

To Treat My Chronic Fatigue, I Ditched Pills for Plants

I was in a bad place. I mean, really bad. Some days I could barely get out of bed. My whole body ached like I had the flu and even the simplest tasks felt daunting. I felt tired, depleted and drained of my lifeforce. My mood swings and depression didn’t help either. It was like my pilot light had been turned off and there was this sense of a dark unknown facing me. I went on this way for months and months without many answers. As a woman in her early twenties, I should have had all the energy in the world, but I didn’t. My mother was at her wit’s end with my daily phone calls crying and telling her I didn’t want to live like this anymore. I can only imagine how scared she was that her once vibrant daughter was struggling to live. Thankfully, she took me to a naturopath to get some help and a second opinion. I went into the office, a full breakdown on the way, and laid down on the examination table. This particular doctor practiced applied kinesiology, or muscle testing, to diagnose imbalances in the nervous system based on the external response of the muscles, which I had never seen before. Within minutes, he had determined I was suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. Relieved to have a diagnosis, I was still left feeling like it was just a blanket term for symptoms the medical world couldn’t explain. It felt like something deeper was going on with me.

As a woman in her early twenties, I should have had all the energy in the world, but I didn’t.

An Herbal Teacher Came to My Rescue

The treatment he prescribed to me was a laundry list of supplements, mostly extracts from animal organs, to be taken at different times of the day and I was left feeling exhausted just trying to manage when and how to take all of these capsules and pills. Though it’s not known what the cause of CFS is, it’s thought that viruses and psychological stress play a big role. What’s even more interesting is that upon doing more research, I found that it affects women significantly more than men, as well as young adults. Feeling completely out of control in my life and in my body, I knew something had to change. I couldn’t go on like this, and neither could my friends and family around me. Right around this time I was studying herbalism, the art and practice of using plants for medicine. I had always been intrigued by the natural world, having been taught at an early age about the ecology of Florida, where my family lived for generations. My grandparents would take me on walks as a kid and point out the trees, plants, birds and bugs we’d pass along the way. Their connection to the earth was instilled in me early on, so it was no surprise when I got older I wanted to learn more about plants and medicinal herbs. My herbal teacher, Emily Ruff, came to my rescue and helped me devise a plan to nourish my body with foods and herbs instead of supplements and pills. She first introduced the idea of food as medicine to me and taught me how to infuse restorative herbs right into my food. Soon, my mealtime went from feeling stressful to inspiring with the help of herbal allies. I’d make things like nettle pesto, packed with vitamins, minerals and kidney support, to slather on my breakfast toast or enjoy as a snack with crackers. Ashwagandha root was another herb I’d mix into peanut butter and honey, which helped to restore my energy, ease my anxiety and offer a restful night’s sleep. I was using fresh tulsi leaves (holy basil), an uplifting adaptogen that supports the body during stressful periods to add extra flavor to everything from pasta and grains to teas and salad dressings. Eating this way was by no means a new idea. Cultures across the world have been using herbs as medicine in everyday meals for thousands of years. But it has mostly been left out from the Western diet, like much of indigenous culture and history has been.

A Farming Internship Opened My Eyes to Medicinal Plants

After about a month’s time, I actually started feeling better. I had more energy, less anxiety and could function pretty normally throughout the day. I continued to feel more and more like myself, so I decided to deepen my herbal studies and apply for an internship at Herb Pharm, one of the largest producers of herbal tinctures in the country. Located in Southern Oregon, it offers a group apprenticeship program to live, work and study at the farm for three months during the summer season. I jumped at the chance to apply and got in. From the moment I stepped foot on the farm, I knew it was going to be a transformative experience, and I felt as if something pulled me there. Walking around the property—what was then about 80 acres of cultivated medicinal plants—I couldn’t help but notice how alive everything felt. There were rows and rows of bright orange and yellow calendula flowers, a magenta sea of echinacea blooms and sweet-smelling chamomile swaying in the breeze. On one of the first evenings of herbal classes, our teacher, herbalist Mark Disharoon, introduced us to a plant spirit medicine practice. Not only were we getting to see firsthand how to grow plants that were used as medicine to treat physical ailments, but we got to see how they also worked on more subtle levels. He had us take a few drops of a tincture, of which he’d only reveal the name after we tasted it and spent time alone outside in a quiet place to sit with that medicine. Sitting there, wondering what I was supposed to be doing, I felt this warmth in my chest. “That’s interesting,” I thought to myself. Then I noticed this gentle energy pulsing from my heart and a flood of emotion and memories came bubbling up out of nowhere. I let myself just cry and feel the pain that I had been carrying the past year. All of the self-doubt, judgment and sadness came pouring out in a cathartic release. Over the next few minutes, the pain transformed into a feeling of gratitude, love and a sense of connection that I wasn’t alone. It was as if something in me dissipated and, for the first time in a long time, I felt safe enough to let go and surrender to what I had been feeling. I collected myself and made my way inside to be with the other students and discuss our experiences. One by one, we all went around to describe what we felt and to everyone’s surprise, there was an exact similarity between our encounters. Each person mentioned how they felt a sensation in their heart or chest, how they grieved something and felt a release and that there was a feeling of love that washed over us. It was astonishing to me.

I felt safe enough to let go and surrender to what I had been feeling.

My Chronic Fatigue Has Faded Into the Background of My Life

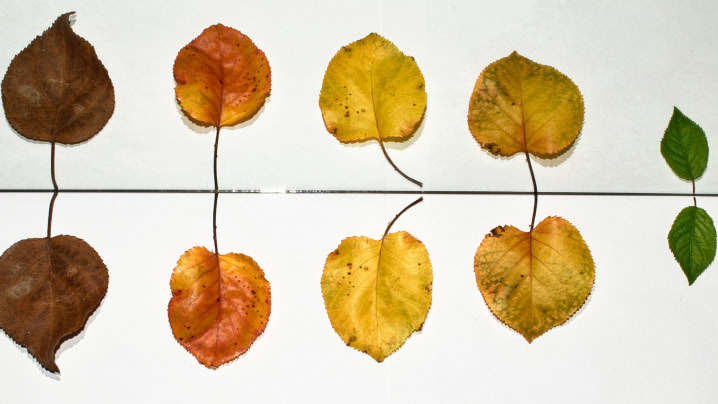

As we wrapped up, Mark was finally ready to tell us what plant we were working with and it was none other than hawthorn. A plant known for its affinity to the heart and circulatory system, hawthorn has an ancient history of use. On an emotional level, hawthorn has been used to remedy broken hearts, depression and anxiety. “It’s a specific medicine for those who have a difficult time expressing their feelings or who suppress their emotions,” Rosemary Gladstar, one of my favorite herbalists, writes. “Hawthorn helps the heart flower, open, and be healed.” I felt an immediate connection to hawthorn and realized that Mark gave us this plant as an initiation to “meeting” the other plants on the farm. This introduction to the psycho-spiritual world of plant medicine opened the door for more messages to come through in dreams and waking life—especially when weeding next to the plants. I’d get ideas about what herbs I could be working with on a daily basis for support with my anxiety, depression and energy levels. I’d be shown memories or visions of the emotions I’d held onto playing out in current situations. It was like I was being shown a movie of my life that someone else was narrating. Since being on the farm and deepening my connection to medicinal herbs, my chronic fatigue has faded into the background of my life. I’ve come to think of that time as an important initiation in getting to know my own limits—trusting my intuition and taking care of myself in a more holistic way that not only allows me to feel more connected to myself, but to have a deeper understanding and empathy for those struggling to find answers and healing. Over time, I’ve learned how to create daily routines and rituals around incorporating these herbs into my food and self-care practices to help me feel nourished and supported rather than stressed and depleted.Like many who journey down the herbal path, I started to think of these herbs as my friends and companions, helping me see that there is far more to this world than what meets the eye and that healing really is possible. They were teaching me in their own way and in their own language, offering me advice, comfort and a sense of community. I’m not special by any means; anyone can do this. Try it for yourself. Sit with a plant, even a house plant, in silence for a few minutes. See what arises. In my experience, all that’s required to hear what messages plants have for us is a genuine curiosity and a humbleness to get quiet and listen.

Zones of Sacrifice: Nature Will Defend Itself, Even Against Us

Hope is sweet earth shaped like a popcorn-bedazzled wand. Mullein boasts a bouquet of fuzzy floret leaves that dance at its roots and invite the hand to touch her. Seasons before the global pandemic, mullein called to make me her ally. She’d dazzle and entreat me from her summer station on the lawn of my neighbor, a devoted, down-to-earth Nana with a grandchild who also danced like sunshine. Nana gave me permission to harvest whatever I saw coming up. I promised to share the medicine. Mullein follows one of my favorite patterns of the sweet earth: “Everything you need is nearby.” And so she grew on the lawn of this beloved, longtime smoker to teach me about the woman who needed her. The kinds of people who would need her soon. And how to prepare me for the grief that would surely sit atop my lungs like pneumonia. The sweet earth teaches us to read her patterns. The sweet earth has a pattern of death. When Brazilian carpenter ants outgrow the forests’ capacity to sustain them, parasitic cordyceps fungi cull the population to maintain the dynamic equilibrium of the forest. That balance is necessary so that one species can’t become too large, as to destroy the ability of the entire system to regulate life. Indigenous people hold sacred the life-death-life cycle. This worldview understands that the death of an excess of carpenter ants will create space for new and diverse life to flourish. This worldview understands the one group of beings does not hold the right to disrupt the homeostasis of the entire ecosystem. The power of disruption is checked by death itself. As an ecological activist and rootworker, I dissolve the false separation between the patterns of nature and social behavior. Human beings are shaped and governed by the ecosystems they inhabit even if those ecosystems contain iPhones, concrete and subways.

What we do in the world matters.

We Are Nature

All-natural even if our diets are genetically modified. Even if we feel separate and enact the violence that flows from our falsehood. What we do in the world matters. Our actions set off chains of reactions within the homeostatic ecosystem that is the earth itself. The disease that she experiences is reflected in the fractal of our bodies. Viruses and other bundles of genetic information called exosomes are exuded from bacteria, fungi and multicellular organisms, like pigs, in response to stress. Stress is a call for help, and this genetic information contains a diversity of adaptive genetic resources for the organisms to make use of. Everything that we need is nearby. The coronavirus received these genetic stress signals emerging from the animals, in particular, the massive pig confinement operations and herbicide-soaked fields of Central China and adapted as all beings adapt. As all beings must. And she came to us, with her sacred communication. From the Chinese case studies, I learned that older folks had the highest mortality rates and I saw corona as just, especially when it displayed the same patterns in Europe. Old people destroyed the world. Ate excessively and had me inherit this shitshow. I saw the earth grieving. Eastern philosophers remember that grief lives in the lungs. The lungs are the interface between the human body and the world. And so the coronavirus became our disjointed relationship and made her home there. The abundance of plants in my world gives me direction as to how much medicine will be called for later. In the early days, I distributed my abundance of mullein medicine to all the elders in my life and friends who knew my game. And I waited until the virus arrived on my side of the world. But my side of the world is wounded and scarred. It has a body politic that is shaped by its past conditioning. In yogic philosophy, past conditioning leaves an imprint or grooves on the subtle body which shape the response of the entire organism. These samskaras, or impressions, are in the words of yogi Dr. Kamini Desai, “Like channels that despite all the potential outcomes we have the ability to create, keep us reincarnating the same results into the reality in repetitive and predictive ways.”

The groves set forth by our racist history came alive during the pandemic and resulted in actual death.

Life in the Samskaras

The groves set forth by our racist history came alive during the pandemic and resulted in actual death. The groves of our racist history have impacted the physical redistribution of brown bodies in places where the air is sickened by the shitshow of industrial life. These folks are asked to be the buffer zone between white excess and its ecological repercussion. This grove, this samskara, is known as a zone of sacrifice. Seventy-one percent of Black Americans live in counties that violate EPA air quality standards. A Black family making up to $60,000 a year is more likely than a white family making $15,000 per year to live next to a toxic facility. Over 78 percent of Black people live within a 30-mile radius of a coal-fired power plant expelling toxic waste into the air. Black people are three times more likely to die from asthma than any other group. Black people are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than a white person, and the same goes for indigenous people. COVID mortality is directly linked to the air pollution that folks of color are positionally exposed to. According to a study by biostatisticians at Harvard University, even a small increase in long-term exposure to fine particle pollution leads to a large increase in the COVID-19 death rate. Black and indigenous disposability is a part of the cultural and ecological samskaras of this country. But hope is sweet earth shaped like a popcorn-bedazzled wand. The institutions created in the samskaras of America’s racist history are ill-equipped to dismantle the structural racism that results in Black and indigenous disease. As our precious communities undergo the pressure of dying under the weight of this empire, our bodies exude adaptive genetic resources in the shape of exomes and viruses, genetic resources that shape-change in the soil and waters surrounding us, that shape-change in the trees and the birds and the insects. Who carry the seeds of our green allies like mullein, so that we can also adapt to live another day here, to become the virus in the chest of this empire and sit our whole weight upon it so that it can die, suffocating under the burden of our grief.

I Lost My Home in a Wildfire

The night that we evacuated started like any other night. I had been working on renovating an old house that my partner and I had just bought. I was exhausted and ready to unplug for the night. A windstorm was picking up in the dry September air. The darker it became, the harder it raged. At one point the power went out, so we checked social media to find that a small fire had started several miles away. In this rural area of the Pacific Northwest, blackouts are common and little fires happen several times a year. There was no cause for alarm at the time. A few hours later, our phones rang out with “Level 3: GO NOW” evacuation alerts. I had enough time to grab our cat, some essentials and a backpack full of clothes before we left. On the way out, after seeing charred maple leaves in the gravel driveway, it hit me that we may not come back to the same place. With no time to take anything in, we started up the car and drove out. We approached a string of yellow headlights and red taillights slowly drifting down the main highway back into town and merged into the procession. I called some family members who thankfully live in the closest city. They welcomed us in with blankets and shots of Scotch. My partner was rightfully ruminating on the impending destruction of the community that he had called home for almost a decade. I was trying to keep calm, repeating that we didn’t know the extent of the damage yet. Cycling through dismay, disbelief and relief from being in a well-lit home among family, we decided to watch Labyrinth and drink more Scotch. David Bowie finally sang us all to sleep around 4 a.m.

Friends and Strangers Stepped in to Help Us

I woke up the next morning to the sound of my partner crying next to me. He was reading the Facebook group for our rural community. Reports were coming in that the local school had burned down. The highway back home was closed off for dozens of miles, with almost everyone evacuated. Our new, old house and the cabin that we had been renting, which contained most of our belongings, were both located deep in the fire area. That was all the information we could get.It smelled like a campfire inside the house. Outside, the air was hazardous and smoky, with flakes of ash falling from the sky. That day, we left the valley to get some fresh air. The next week or two, we split time in hotels and Airbnbs, replacing some basic-necessity items, searching for information on what happened to our home, figuring out what shape our lives were going to take and trying to find some peace. The news of the fires spread quickly. We received an immense surge of support from so many different people in our lives—family members, close friends, old friends who we hadn’t talked to in years. Even random strangers. People reached out on every possible platform, trying to help in any way they could, offering to donate to help us. We were incredibly grateful, and even a little overwhelmed in responding to them. It was hard to put aside our pride and seek help, but we’re glad we did. That support really helped our morale and our ability to feel somewhat secure in the situation.We were lucky to be connected to a friend’s relative who had a vacant apartment that she had walled off in part of her house. We would come to know of many other neighbors of ours who lived in hotels, stayed at friends’ houses or camped in fields for far longer.

This disaster has brought out the best and the worst in everyone connected to it.

The Wildfire Taught Us Detachment From Material Objects

About a week into our displacement, we were sent a grainy photo from a crew of first responders that had visited our cabin. A low-lying pile of rubble sat where the cabin used to be. In the driveway, my school bus, which my family and I had converted into an RV, was completely torched. We knew at that point that we had lost our most prized possessions: the sculptures and molds that I had created, including a large, intricate model that had taken two years to make; a cedar-strip canoe that my partner had built and taken out on the river every summer; and all of our old journals, heirlooms and ephemera that we had saved for our entire lives. Thus began a process of detachment from objects. We had been fearing this and gradually began to reckon with it over the course of our displacement. Still, it stung, and hard.Much of my identity was wrapped up in my artwork. I could not escape the idea that all of that time I had put in for the last two years had gone to waste, as well as all the time I had spent on other art that I completed and kept. I mourn the art that was given to me by my friends, which carried a little part of them for me, and which I cannot replace. This regret has diminished over time, but it has by no means gone away in the months since the fire. But I try to focus on the facts. I have gained skills from those years of practice, and I still have those relationships, even if the objects produced from them no longer exist. As for the non-sentimental items, losing them has been more like an innumerable series of small disappointments and inconveniences. It’s annoying to realize a dozen times a day that you don’t have some little thing that you used to, like a tea kettle or a nightshirt. In time, I have stopped feeling those disappointments almost entirely and have just gotten used to it. We are fortunate that we have the means to replace them. Those means are a matter of privilege. We have the advantage of a supportive community. We had the outlandish luck of having bought a house less than two months before the fire—insurance has allowed us some compensation for what we lost. We have stayed afloat on the grace of the resources available to us.If this fire had happened two months earlier, we would have been in the same situation as hundreds of other people in our community, and many thousands in the American West, who don’t have that protection. There are families, often living in trailers or rental homes, who either couldn’t afford insurance or were gravely underinsured, and lost everything. We have worked to help them out as well by giving them a large portion of the donations that we have received and by encouraging others to donate to organizations that help them directly, such as the American Red Cross and local community-action movements.

Insurance Companies and Thieves Attempted to Take More From Us

This disaster has brought out the best and the worst in everyone connected to it. Right after the fire, as roads were opening up, there was a rash of break-ins that occurred due to thieves taking advantage of residents’ extended absence. Folks watched out for each other and stepped up to guard other properties against suspicious cars making their rounds and lurking in driveways. There have been numerous incidents in which some poor jerk lost their pre-1980s home and either couldn’t or didn’t want to pay thousands of dollars for asbestos removal, so they loaded up the remains of their home into a trailer and dumped it into others’ yards. Neighbors have been coming together over Facebook to try and ferret out the dumpers responsible.We have also witnessed the tactics that insurance adjusters use to avoid paying out due coverage. Our own adjuster immediately tried to deny us coverage, arguing that our property had been seized or destroyed by a civil authority, not because our house was uninhabitable due to a disaster. This was obviously untrue. He tried to enter assertions onto the record about our situation that were false, and which contradicted our reports and evidence. If we hadn’t read his arguments and our contract carefully, we could have easily let him screw us out of our coverage. While being honest with them, we have had to be careful not to say anything that they could possibly misconstrue and weaponize against us. Truth be told, I’m nervous even talking about it for an anonymous article. I can only imagine that this must happen to plenty of people all the time. If you don’t understand a contract, get legal help. It’s worth it to not take these companies’ word for granted. Their profit motive is in line with not fulfilling their obligations.

The most important thing to take away from this experience is that stories like mine are becoming increasingly common.

Wildfires Will Continue to Ravage The Land Unless We Take Action

Our community is still scarred, but we are rebuilding. Logging crews and utility companies have been working long days to remove dead trees, control potential landslides, and rebuild downed networks. These days, we are witnessing crews of 50 or more volunteers helping with clean-up. Neighboring towns have donated tons of clothing and home goods that have gone to good use. Church organizations, and the local school that hadn’t burned down, have opened their doors to distribute donations to the people who need them. As my partner and I rebuild, we are leaning heavily into fire safety on our own property, because it could happen again, even more easily now that our forest is full of dead trees.The most important thing to take away from this experience is that stories like mine are becoming increasingly common. Our global climate is warming at an increasing rate. According to NASA, atmospheric CO2 has jumped up dramatically since 1950—about 37 percent higher than the previous largest concentrations of the past 800,000 years. Global temperature, which used to fluctuate up and down before 1940, has been steadily increasing since the 1960s in a way that is not consistent with natural behavior. We are now really starting to see the effects: according to data from the NIFC, the area burned by wildfires in the U.S. has steadily increased since 1983, when reliable estimates based on federal and state reporting became available.We have the technology to change this. We need to wean off our dependence on fossil fuels and transition to clean energy. This is a problem that runs deep in our transportation, production and farming infrastructures, and businesses need to be brought to task in taking their own responsibility for part of it. We all need to work together in our own societies and get our representatives to help this happen. We can volunteer and vote for those who take this as a priority, and we can limit our own carbon footprints by driving as little as possible and sourcing our goods as locally as possible. We can stop this cycle from burning us alive, but we need to deal with it urgently if we hope to reverse it.

The Promise of Technology Is a Threat to Our Biology

The 1980s were an exciting time to be born. TV and movies preoccupied our minds with science fiction and outer space. Nintendo was fresh on the scene and robots captured our fascination. We watched reruns of The Jetsons, where Rosey the Robot kept the house clean and put food on the table. In movies, robots were tasked with terminating every last one of us. One thing was clear: The future, in terms of progress and problems, was tech.I was a normal, white privileged, lower-middle-class kid from a blue-collar town. I played street hockey outside with my friends, a very popular thing to do in the ‘90s. We developed skills to retrieve pucks from the sewer, how to look out for cars, how to get up from scrapes, falls and bruises. We played outside in the cold. We learned from the pain and we became stronger for it. We didn’t worry about helmets until much later, when they started to become essential bike-riding equipment. Better tech meant better protection from a dangerous world.It seems technology is what humans naturally develop. If we don’t like something, we try to improve upon it; with improvements come new challenges, and demands more innovation. This repeats until the future of our species and the direction of the planet now lies in its hands. Welcome to the Anthropocene: a testament to our innovative spirit.

Not even sex is safe from being replaced.

Computer Technology Provided Infinite Knowledge Immediately

Our family got its first computer in 1994: Windows 3.11 on an Intel 75MHZ processor, 1.19 GB hard drive, CD-ROM and a 28.8k dial-up modem. Meanwhile, I was in middle school making friends. Video games, computers and the internet provided a reprieve from the brutality of adolescent social life. Technology created a safe space, a digital womb.Logging on to the internet for the first time was like entering Stargate; we had to put sticky notes on the phones so nobody accidentally terminated our session trying to make a phone call. It took hours, sometimes days, to download songs from Napster. It was cool to get free music but it sucked having to wait so long. In only a couple of years, the technology changed. Suddenly we were always connected with high-speed broadband. Soon, infinite knowledge was at my fingertips. I wasn’t even out of high school yet and was addicted. AOL Instant Messenger took me hostage almost immediately. Being captive to the screen meant protection. It was a great, safe way to pass time indoors and be social with friends. Call it cyber Stockholm syndrome. It was a seamless integration, a usurpation of my attention. I knew technology was the future, so I followed what my friends were doing and enrolled as a CS major. After all, I was still a kid and just wanted to be accepted.

Smartphone Fever Pushed Me Into the Wilderness

Within a month of starting college, 9/11 happened. I was in between classes when I heard the news. It was a tech school that issued every student a laptop, and the first in the state to have wireless internet. Every single laptop in front of me in the lecture hall was playing the same devastating footage. The internet kept us informed about “what really happened” and privacy concerns in this new era of national security. The easy access to information was a rabbit hole. I had no idea what I was doing in school anymore. The digital womb was starting to feel like a trap. My inner animal wanted to be free, but it couldn’t ignore how the world was so rapidly changing. And because of our progress, I was able to stay informed from the confines of my laptop. Always connected, always informed, always aware of the environmental problems facing the world. After three semesters I failed out, eventually enrolling at community college to study liberal arts. The disruptive power of technology was gaining momentum. School and work rapidly became more and more computer-based. The computers got smaller and became smartphones. The internet was always with us and all this screen time was disorienting. I had had enough. I went to Oregon with only a backpack of clothes and my skates. I peeled myself from my screens and into reality, amongst the old-growth forests. It felt natural and right, surreal and alien, dangerous, but safe and calm. This was when I had a real opportunity to reconnect with the world around me, to reconnect with the lost ways of my early childhood; the here and now. I needed a new phone so I opted for the cheapest, most basic flip phone. This smartphone hiatus lasted three years. It showed me the attention-sucking nature of these devices. I hated how, in conversation with any number of my friends at any given moment, someone would lose interest in the “here and now” and compulsively check their phone. I felt like I was surrounded by addicts. I grew to hate smartphones. I hated how they owned my friends. But as I was preparing for a drive back East, I wanted a GPS, so I asked my dad to send me his old smartphone. Like any addict thinking just this one time, I relapsed.

We are more connected than we’ve ever been, unnaturally hyperconnected and yet also more isolated.

Technology Is Changing Our Relationship to the Environment

Is our technology just part of the natural world, some natural sequence of behaviors for any intelligent life? If making tools and technological progress is what we as a species are supposed to do, why even try to resist? Are we just mechanisms for entropy, converting matter from one form to the next in order to make our existence as efficient as possible? Do we exist to replace what already exists with that of our design? We are the changing universe, which is changing itself.Ultimately, technology is changing our environment and our relation to it. Every advance makes possible what once wasn’t. These changes don’t always jibe with the institutions of evolution that engendered us to begin with. At the same time, they create novel ways for self-expression and coping. Technology, while being a driving force for climate change, allows us to be whatever version of ourselves we choose, while also protecting ourselves from the dangers of reality. We can be whoever we want to be on the internet, and we have virtually zero consequences for our actions. We are more connected than we’ve ever been, unnaturally hyperconnected and yet also more isolated. Our brains are hyperstimulated as our bodies sit idle, staring at a collection of bright dots. (The solution? Stand-up desks!) Our progress is paradoxical, almost as if the more we try to avoid chaos and death, the closer we get to it. Some scientists predict that our species could be extinct in as few as 80 years. This may well not be the case were it not for our progress.

Tech Will Inevitably Integrate With Our Biology

Is more progress our only hope? While the world burns, we will have VR to experience education, concerts and waiting in line at the DMV. Eventually, our bodies’ cells will become obsolete, unfit for this brave new world. Artificial intelligence will become smarter and faster than humans in every way, and humans will have no choice but to integrate technology into their biology. We will preserve our sentience in an entirely virtual ecosystem. We will be bodiless gods of our own universes. Not even sex is safe from being replaced. Does the availability of online pornography and life-like sex dolls suggest that soon we won’t even need partners? Sperm and egg will be synthetic and made to order, and birth will be an optional, virtual experience for women. Reproduction will be created in labs by genetic counselors under very controlled conditions. Perhaps it’s true: There is nothing new under the sun. But, it will eventually die—and when it does, if we want to exist, we will need a way to do without it. There are plenty of other threats to our existence in the meantime. For example, ourselves. We have no choice but to find out if we can have our own subjective worlds without a biological substrate. We will keep working to be safe, making progress on the problems of our progress. In the meantime, go outside.

Climate-Proof Cities Don't Exist

In below-zero temperatures, the lake holds onto its heat more than the shoreline surrounding it, causing a thick morning fog to float over the surface, the gravitational pull of a diaphanous moon to the water. Lake Superior is so large that it has tides like an ocean. It is December 2019, and I am sitting near the Aerial Lift Bridge in Duluth, Minnesota, almost 1,200 miles away from my apartment in Brooklyn, watching ice chunks float in the harbor. For a short period of time during my childhood, my father was the city engineer and in charge of this bridge, most known for letting iron ore ships in and out of the city. Earlier in the year, Duluth—situated in the most southern corner of Lake Superior—was named “the most climate-proof city" in the U.S. by Harvard researcher Jesse Keenan. When I first read about it in The New York Times, I laughed. Our Great Lake may provide an abundant supply of fresh water and a consistently cool year-round temperature compared to the rest of the continental U.S., but my experience growing up in Minnesota was of a state home to an almost cliquey kind of eccentricity I couldn't quite pinpoint to friends on the East Coast—and also a state government still actively reckoning with its positionality in the current climate crisis. I considered the term "Minnesota nice" an ironic joke, lying physically beneath "friendly Manitoba." Our state is more accurately home to road rage on I-94 and meat raffles held at local Lutheran churches. I recently returned to a photograph I have of two of my family's Siberian huskies from a camping trip when I was a kid—one red, one black, their bodies and bright blue eyes pitched halfway between the fire and the tent, the lake just visible behind them. It seemed more like a nostalgic Polaroid from a photo book than a real shoreline currently in the throes of relentless development.

I Can See Why Duluth Is Considered a Climate Refuge City

In many respects, Duluth could, in fact, be considered a ripe candidate to balance on both a metaphorical and literal precipice of change. The city stretches 30 or so miles along the steep shore of one of the largest freshwater lakes in the world by volume, and is the most inland ocean port in the world. Its immigration history is as rich as its rock cliffs: Iron ore production began in the mid-19th century and was the main source of its initial population growth.In 1870, Duluth was the fastest growing city in the U.S., drawing thousands of families from all over Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. Beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, Duluth, like many American towns that traditionally relied on mining exports for income, shifted to tourism and tech—so much so that finding a public campsite on the lake has now become almost impossible, due to the abundance of privately-owned land. It costs a hefty sum to see the sunrise these days: The lodge my family frequented growing up is now run by a resort chain that charges at least $130 a night depending on the season. There is a direct correlation between development and levels of runoff and septic waste into the lake, contributing to algal blooms that are increasing due to global warming. According to the University of Minnesota-Duluth, Lake Superior is one of the fastest-warming lakes in the world. My father says the increase in unpredictable weather contributes to the shoreline’s maintenance as well: “Because of the frequency of storm surges and rising lake levels, the shoreline sees continuous erosion issues that must be dealt with—many of those areas in tourist areas and having impacts to the local economy.”

Can a city really be climate-proof if it hasn’t dealt with the environmental impacts already leveled upon its neighboring indigenous communities?

Being a Climate Change-Proof City Is About More Than the Weather

Can a city really be “climate-proof” if it hasn’t dealt with the environmental impacts already leveled upon its neighboring indigenous communities? I started to ask myself, "What is a climate-proof city, anyway?" Certainly not one that is immune to its past, both its nostalgia and its history of colonization, beginning with immigration but one that continues on in the form of fossil fuel transport through indigenous lands. I thought of notes from Lorine Niedecker's poem “Lake Superior”: "So—here we go. Maybe as rocks and I pass each other I could say how-do-you-do to an agate. What I didn't foresee was that the highway doesn't always run right next to the lake." There is always a highway with gasoline-fueled traffic nearby, and now, the encroaching expansion of Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline carrying tar sands for over three hundred miles between Alberta, Canada and Superior, Wisconsin, right next door to Duluth. Proponents of the pipeline and Enbridge executives justify that it “already existed,” and yet, the “repair” expands and reroutes the tar path through indigenous lands with multiple treaty violations. The pipe will carry twice the amount of oil it previously did, slated to be the largest tar sands pipeline in the world. It will now cross more than 200 bodies of water and 800 wetlands that it can potentially leak into. If the local Minnesota government is serious about global warming, it should stop approving modifications of old infrastructures that pose harm to communities, specifically ones that have lived here for generations. There are eleven reservations in the state of Minnesota (under the names of Ojibwe, Chippewa, Dakota and Sioux), one of which has access to Lake Superior and houses a national monument run by the National Park Service that draws just under 70,000 visitors a year. Karen Diver, the chairman of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa from 2007-2015, has further stated in direct response to Keenan’s report: "Our way of life is so tied to a healthy natural environment. More people, more strain, more pollution. From my perspective, we haven't even figured out how to act in a positive way with our indigenous people here." The pipeline seems to be a further example of her point.

There is a world dying and a world being born every second.

Duluth May Not Be Capable of Welcoming Climate Migrants

While I don't have one singular response to Keenan's report, reading it has brought forth vital questions for me to consider in our inevitable future of climate migration: How do regions accept new groups of people, when they have yet to converse with their own sense of memory and loss, and especially when some have not even started to dismantle their violent relations with the local indigenous people? What kind of space does shoreline that was never "mine," but holds a deep well in my body and mind's memory, occupy? What I do know is that I am committed to preserving Duluth and its surrounding landscape as a place of community, beauty and healing, and not one of further exploitation.“In an age of global warming, there is no background, and thus there is no foreground,” writes philosopher Timothy Morton in Hyperobjects. “It is the end of the world, since worlds depend on backgrounds and foregrounds. World is a fragile aesthetic effect around whose corners we are beginning to see.”Reading this, I’m reminded that there is a world along the shore that has already disappeared, and there will inevitably be another world that climate migrants move into. These so-called separate “worlds” are just prominent changes in one ever-unfolding experience. There is a world dying and a world being born every second. The constantly icy waters my sister and I dared each other to dip our hands into each summer is a world that is now gone—the warming shallows touching the pipeline is another world yet to come.

What It’s Like to Speak Up for the Environment in Front of Oil Executives

I went to Aspen for the first and only time in the summer of 2019. During my first night, I slept in my car on the street, masturbated to porn on my phone and woke up early the next morning to a Latino construction worker leaning on my passenger side window.“No, no, no! The steps going in over there!”It was a nice sunny day in Aspen and the first day of the Aspen Ideas Festival. I’d been invited through the Ideas Scholars program, which provides free festival tickets to “a diverse group of global leaders who are selected for their work, accomplishments, and ability to transform ideas into action.” At the time, I was a master’s student and on the Environmental Film Festival team at Yale. My guess is that my invite had something to do with those four letters: Y-A-L-E.That next night, I found myself alone in the luxury suite of a hotel. The space was far too big for me, and I thought for a second maybe that’s why rich men are always filling their homes with women and parties and shit because, otherwise, the cavernous-ness of wealth would constantly be whispering. I sat on the king-sized bed and looked at the fake fireplace that burned the decomposing fossils slowly ruining the planet and wished they’d have just paid me the cash for however much this room cost and I could go sleep in my car again. It’d help a lot with rent. I snapped back when my phone buzzed. There was an email from some folks at The Atlantic."The Atlantic requests the pleasure of your company for a private breakfast and discussion. “What policies will drive meaningful action on climate change?” Underwritten by ExxonMobile".

I think that basically nobody cares about climate change.

The Festival Headquarters Was an Anachronistic Fantasy

A few days later, I found myself struggling out of bed, hungover, but with just enough time to get to the hotel to talk to whomever about environmental meaningfulness. Walking into Hotel Jerome in Aspen is like being transported into a 1912 campaign rally for the Bull Moose Party, which gave us both meaningful conservation policies and meaningful eugenics policies—and thus, our National Parks and the Holocaust. Inside, it is artificially dark, suggesting some time before the lightbulb, and the walls are strewn with the heads of dead animals and the portraits of dead white men dressed in military regalia and American flags. The furniture is all built from some combination of the flesh of dead trees and the fur of dead animals. In every act of its public persona, Hotel Jerome hints nostalgically toward a time when the relationship between man and nature was intimate and ruggedly reciprocal. And yet, in reality, it’s a celebration of a time when the rich, white men in portraits traveled West to places like Aspen to nostalgically “LARP” a frontier-era that never existed. The real frontier was horrific, no place for blue-blooded, sport-hunting Ivy Leaguers. Which makes Jerome a confused place today.And so, there I was, in the lobby of Hotel Jerome at 7 a.m., when the next generation of white male Ivy Leaguers with invites from some of the world’s most powerful would gather to discuss the unchanging, abusive relationship between man and nature. I was standing there in the unrealistic darkness, in my Western-patterned button-down shirt, when a white woman in a white dress walked up to me.“Sir?”“Hey, yeah!”“Are you looking for the breakfast?”“Yes!”“Follow me.”

The Executives Greeted Each Other Like College Kids

As she led me through a labyrinth of hallways deeper into Jerome, we chatted. She was nice, about my age and had the graceful professionalism of someone working 60-hour weeks in Manhattan and seeing a therapist. The Wheeler Room in Hotel Jerome is as ridiculous as the rest of it. Everything’s white. Lacy drapes adorning 20-foot tall windows drift in the breeze and morning light. And in the middle is one gigantic table built for 30. If the rest of Jerome is a shrine to some imagined masculine earthliness and death, the Wheeler Room is a temple for the heavenly feminine, a place for more atmospheric or aspirational conversations.As I got there, people in suits were already sitting down at their assigned seats, backslapping and laughing in a way that suggested, “This is just like the old college days, eh?” I quickly found my name card and sat down. To my right was a reporter for Axios, who was frantically and only half-secretly scrolling to her voice memos app beneath the table. Record.The editor of The Atlantic seemed to be in charge. He was bald, kind and introduced the gathering with something like, “Here we are in the beautiful Wheeler Room in Hotel Jerome in Aspen, Colorado. Look at this group! Exxon Executives, McKinsey Partners, and even academics from Brookings to Harvard to Yale! In today’s session, we will be trying to answer the question: What policies will drive meaningful action on climate change?”

The Environmental Discussion Focused Only on Nuclear Energy

After some more hopeful remarks and a casual bite of food that went down in a way that you know he didn’t taste because he was too nervous, he began. Here’s a brief, remembered transcript of the meeting: Atlantic Editor, to an Exxon Executive: You’re in charge of environmental policy at ExxonMobile. How have y’all been thinking about policies that will lead to meaningful action on climate change?Exxon Executive: Well, I know this sounds crazy but we think that nuclear energy is the future.Someone Else: Yes, I totally agree.Harvard Researcher: Well, here’s a small problem with nuclear but, yeah, I also agree.National Geographic Editor: Why are people so afraid of nuclear?Brookings Fellow: I know, I don’t get it! It’s so good.Chevron Advisor: I mean, yeah, it won’t work forever, but as a transitional source?Exxon Executive: Yeah, totally. It’s the only thing.Former USDA Undersecretary: If only we didn’t live in a democracy we could just like, do nuclear everywhere without anyone stopping us.Axios Reporter: I mean, do we live in a democracy?Everyone: [Quiet laughter.]Atlantic Editor, speaking to me: You’re the director of an environmental film festival, why don’t you tell all of these people what “meaningful” environmental storytelling is to you.Me: [Having just shoveled too many eggs into my mouth] Well, I think that basically nobody cares about climate change.[The room falls silent. One food server falls wide-eyed as he pours more coffee for the editor-in-chief of National Geographic. The woman in the white dress gasps audibly and covers her mouth with her right hand.]Me: Or at least…well, let me start over.[I think for a moment and look across the table at The Atlantic editor, who knows what I’m thinking and agrees. There is a serene moment when the editor and I stare at each other. The editor sees I’m finally realizing that the people in power are not up to the task of addressing our deteriorating environment. For generations, this has been true and nobody talks about it. The editor watches as I struggle to say something that would change the conventional minds of the table. For a moment, the editor regrets asking the question and putting me on the spot. For years, I will wonder why I was invited to this event in the first place, and the answer might be that sometimes the editors at places such as The Atlantic like to bring in young “global leaders” into white rooms in the back of hotels in Aspen over breakfast to show them what we’re really dealing with.]Me: [Having fully cleared his mouth of eggs] I mean, in practice, we’re all climate deniers. The question of what is “meaningful” has nothing to do with solving the material problem of carbon in the atmosphere. It has to do with whether our collective efforts and public policies align with huge mythical narratives of what we imagine as the good life. I mean, for me, any policies that incentivize the reassessing of cultural values in order to better respect nonhuman life on this planet—and push the public to feel more accountability and kinship with future generations of humans—would qualify as meaningful action. Exxon Executive: I mean, yeah, it might be important to think about why people don’t like nuclear.Brookings Fellow: Yeah because, I mean, nuclear is awesome. It’s our only chance.

I kindly excused myself from her presence, quietly threw up in a nearby garden, started crying and called my mom.

Our Globalized Economy Is Heading Toward an Iceberg

When I escaped Hotel Jerome and made it back out into the morning light, Aspen was just waking up and I felt like I wanted to punch someone. I turned to my right and there on the sidewalk was the only female chief art critic in the history of The New York Times. I didn’t punch her but wanted to.“You’re Helen Smith, right?”“What? Yeah.”“So what’s the deal with climate change art? Who’s making the best work?”“Uh, I don’t know. I haven’t really thought about that. People mostly just make art about identity these days, you know? But yeah, I’m not sure. I’d have to think about it…sorry, it’s early. I haven’t had coffee yet.”I’m not sure if it was the hangover or eggs or the portraits of old men or animal heads on the walls in Jerome. Or maybe it was just the simple experiential fact that we are sailing the Titanic of a globalized interconnected economy toward an iceberg with no one behind the wheel. But I kindly excused myself from Helen’s presence, quietly threw up in a nearby garden, started crying and called my mom.

The Case for Farming as an Alternative Treatment for Anorexia

When I was 19, my parents and doctor sent me to an eating disorder clinic for anorexia, bulimia and body dysmorphia. After four months of working with a multidisciplinary team, I “graduated” from treatment. They advised me that to maintain the progress I made, I needed to participate in something every day to reinforce what I learned in treatment. For me, that meant AA meetings at a West Village LGBTQ center, mediation classes and therapy with a woman from the rehabilitation center.I didn’t realize until much later in my recovery that sitting in Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings only heightened my sense of isolation and depression. I concluded that, like an alcoholic or narcotics addict, I possessed a chemical imbalance that demanded attention. But unlike a drug addiction, sex addiction or alcoholism, we cannot live without food. It wasn’t until I visited a nutritionist in Israel two years later that I was opened up to the world of mindfulness in eating disorder recovery. My nutritionist explained the distinction between addiction and eating disorders, something that seemed radical to me. She emphasized the importance of self-compassion. I started to accept that there would be days that I returned to certain behaviors, but that didn’t have to mean my recovery was undone. Each day was separate, and each meal needed to be treated in isolation rather than in conjunction with the meals before and after it. Before then, I couldn’t distinguish between a chemical reliance and my eating disorder.

What Started as an Escape Turned Into So Much More

A few years later, I experienced real heartbreak for the first time, the kind that will lead you down all kinds of existential rabbit holes. It brought up an eagerness to return to my disordered eating behaviors: binging, purging, restraining and exercise bulimia. Determined to not allow this experience to erase all the hard work I had done, I decided to take action. I reached out to family in Humboldt, California to ask if I could stay with them. I knew I needed to remove myself from the situation, and thought it would be a pleasant place to heal.In Humboldt, I started working on a farm that practices radical sustainability. This is a process in which sustainability is addressed from the bottom-up. Set along the Van Duzen River, the farm values biodiversity and incorporates holistic planned grazing. This is a system of incorporating the rearing of livestock with the production of crops. The goal is to help regenerate the land and the soil through a total integration of all aspects of the farm. While I was there, they had chickens, turkeys, cattle and the oxen that provided draft power as an alternative to gas-powered tractors. The oxen require no fossil fuel and eventually they become beef, continuing the cycle of sustainable practices.

I believe regenerative agriculture can restore not only the damage done to both physical lands, but our personal connections to them.

How Mindfulness and Eating Disorders Are Linked

I was surprised to find a common link between some of the farmers and me. A few of us had experienced a similar history of yo-yo dieting and starvation. As we would make our way down the strawberry patches, harvesting berries and picking away the culls, we would share stories. Many of them included our personal history with anorexia, binge-purge and body dysmorphia.I believe regenerative agriculture can restore not only the damage done to both physical lands but our personal connections to them. It is the focus on the micro aspects of eating that allows an eating disorder to run wild. Thoughts of the self become all-consuming, putting our lives on autopilot. This extends to what we put in our bodies, when calorie-counting becomes a transactional matter leading to malnutrition and severe depression.On the farm, my favorite task was picking vine tomatoes and harvesting peppers. The hothouse was so warm that it made me sweat, and I loved being covered in a dusting of green tomato perfume. I looked forward to finding oddly-shaped peppers. Later in the season when we harvested squash, I looked for the ones that were the bumpiest and most misshapen and took them home.

Food Is So Much More Than Just Calories

A common issue during eating disorder recovery is that people push their bodies into recovery before they are mentally capable. When I found myself taking the time to pick through the wonky veggies or to look for the culls, it was one of the first times in a long time that I felt fully connected to food. Upset that no one else seemed to want these beautiful vegetable creatures, my mind was on food waste.When I was in the bulimia stage of my disorder, my food waste was off the charts. I would buy things just because I knew I could easily throw them up. Things like ice cream and sweets were always a go-to as I knew my body had been trained to reject them. Going to the market almost daily just to buy purge-inducing food was a very low point in my disordered behavior. Speaking to my peers, I have found this was not unique to my experience. Each week when I do my grocery shopping in my London neighborhood I’m shocked by how affordable excellent quality fruits and vegetables are here. Then I immediately think of my home in Los Angeles, and places like Erewhon and Whole Foods that have capitalized on wellness culture and made it nearly impossible for a person living on an average salary to eat locally-sourced produce.The United Kingdom has become a hub for innovations in the regenerative agriculture movement. Many restaurants in London have partnered with farms around England as a response to the demand for ethically grown produce. Even my local produce shops in Hackney sell ethically-grown foods, and my weekly tab never exceeds £32.

Focusing on our macro relationship with the food ecosystem rather than the micro personal relationship can lead to real sustainable recovery.

What Makes Farming a Viable Alternative Eating Disorder Treatment?

For people like me, with a history of disordered eating, conscious consumption is unavoidable. Early in my recovery, I believed this meant making sure I ate at the scheduled times and got in enough calories to satisfy my therapists, doctors and nutritionists. I have since come to understand that the last step in my recovery is giving food more thought. This includes reconnecting with foods I had previously written off merely for the sake of their higher caloric content. I have a deep sense of gratitude for the food I consume. Not only am I more aware of the hard work that goes into its production, but I am finally able to enjoy eating.Sending someone to a farm won’t automatically lead to a healthier relationship with food. But I hope it can offer an alternative approach to the standard Western treatment for anorexia and disordered eating. Hospitalization and clinical rehabilitations lack a connection between personal experience and the world at large. People who are struggling emotionally need to feel like they’re part of something. Finding this missing link is vital, and often transformative.Focusing on our macro relationship with the food ecosystem rather than the micro personal relationship can lead to real sustainable recovery. These days I look forward to biking to my local fruit and veg shops, planning what recipes I am going to cook for friends and family. It’s so far from anything I thought possible.Getting in touch with food through learning about biodiversity, regenerative practices and soil health can not only impart valuable life skills surrounding food, but they also offer a deeper kind of mindfulness. This is far from the “mindfulness” tips we see on Instagram, telling us to journal or run the bath to calm our thoughts of restriction and binging. This is a mindfulness that incorporates a radical self-care that considers what a person is struggling with—in this case, food—and provides more thoughtful alternative approaches.If you or someone you know is struggling, I urge you to look into treatment that can provide lifelong tools and a total expansion of the way we look and talk about food. I ask that you consider the harmful nature of the current rhetoric surrounding eating disorders in the West. We need to start to look at reconnecting with the larger food ecosystem as a method of healing and recovery.

It’s Time to Start Growing Food With Urine

Growing food with urine is safe and effective and should be a common practice. As a biology artist with a background in agriculture, I’m interested in the ways humans can shift their relationship to the earth from parasitic to symbiotic, and using pee to grow plants is one simple way. Synthetic fertilizer reduces biodiversity—it’s a leading cause of pollution and could easily be replaced with a daily byproduct of human life: urine. What if we could help dismantle the patriarchy and close the consumption loop? And what if pee helped? What if pee helped preserve and increase biodiversity? What if pee saved our relationship with the earth? What if pee saved lives? It sounds dramatic, I know. But hear me out.This article will touch on the extraction methods of synthetic fertilizer, briefly compare the makeup of urine to synthetic fertilizer, roast the toxic relationship the majority of humans have to Earth, provide a nuts and bolts how-to that anyone can do, and answer frequently asked questions around peeing on plants.

Mother Nature Needs Our Love for Us to Survive

I’m a sensitive person and know I’m not alone when I say that I feel the earth sort of groaning under the pressure of human life. I have nostalgia pangs over the biodiversity lost in all the places I’ve known for so long, and these pangs are usually followed by an urge to run away to a new place for a fresh start. With that fresh start comes a new baseline and an uncomplicated “just the facts, ma’am” getting-to-know-you of the place. A common human experience has been one where we long to escape the damage we’ve caused, fall into brand new love of a new-to-me environment and explore it—then we colonize the shit out of it. “Let’s see what’s under that mountain over there, and under that forest.” No stone goes unturned. We become the invasive species (here’s looking at you, Mars). It seems that, whether we go or stay, the vast majority of humans need to come to terms with our role on this rock and the wake that we leave, lest The Great Nothing That Consumes Everything stays on our heels. Up next, the Sixth Extinction, while we just chase our species’ tail and squabble over that last spacesuit.This might be a stretch, but what if we look at all that through the lens of patriarchy? We already do, it seems. Mother Earth and mankind are old tropes. Certain groups of humans have been trying to glorify and force their dominion over the earth for how long? She won’t submit, bless her, and she’s ready to swear off man altogether, threatening to burn the house down. I can’t say I blame her and she has never been known to make an idle threat.What if we could stay together, though? I imagine a sort of couple’s therapy, the earth and her most dominating and draining lovers. We’d promise to change and if she just wouldn’t be so withholding and get so worked up and always superstorm and polar icecap melt on us then…no, we’re past that point. It’s past time to listen to what she has been saying all along and be in this relationship, to give as much as we take. At this point, it feels like we can never make up for all the shit we’ve put our old lady through and we just can’t help it, but down the block, there’s this redhead, Mars, and she sure seems like a hot little number. She doesn’t have much, but she’s sweet. Nothing a little colonization won’t fix, if you know what I mean. But Earth is still so good for us and she just needs us to love her for it to work. Really love her. And she wants to try golden showers. Don’t be nervous.

Earth is still so good for us and she just needs us to love her for it to work. Really love her. And she wants to try golden showers.

Using Liquid Gold as Fertilizer

The use of properly diluted fresh urine as a nutrient source for plants is a safe and effective practice that protects human life and promotes a healthy environment. It’s a practice that has been commonplace for public works for petrochemical in other countries but is pretty much taboo for Western culture. Sure, we have reclaimed water for irrigation on golf courses, a similar concept, but we can simplify, broaden and personalize the application. Here are some rapid-fire fun facts.Urine is not a very effective vector for disease (as opposed to solid human waste), which makes it safe and simple to use as fertilizer. It has pretty much the same salt, mineral and general other constituents as the ubiquitous moist, crystalline, blue house plant food concentrate, but your body just makes it. For free. All day. The same house plant food company strip-mines and mountain-top-removal-mines for nearly the same salt and mineral content that we piss away multiple times a day. Those mountains are more than sometimes home to endangered species and indigenous populations of humans that are then “displaced” in order to access the materials under them. Urine is great news for all the mountains since it is so plentiful and free. Did I mention it’s free? Here are some other crazy stats, if you’re into that: The average American urinates into about 12 gallons of potable water each day, or 4,380 gallons a year, turning 1.25 year's worth of drinking water for one human into blackwater. Blackwater is a major contaminant to drinking water sources, lakes, rivers and bays, posing a health risk to humans and suffocating greater ecosystems. Meanwhile, a year’s worth of urine from one human can grow enough wheat to make 365 loaves of bread. We pee a loaf a day.

How to Change Your Fertilizing

Replace your mined petrochemical fertilizer with homegrown golden showers (for your plants). For house plants, mix one-part fresh urine with nine parts water and apply, repeating every third time you water. For herbs and veggies, mix one-part fresh urine with five parts water for a stiffer drink and water as usual. Vegetables are heavy feeders, so repeat every other time you water your garden.The great news about lawns? You don’t have to dilute if you don’t want to. You can put your urine in a watering can and sprinkle it sparingly over your turf. For general use, you will need to supplement with iron (compost, worm castings, blood meal, menses) every so often, but you will have to do that with the store-bought stuff, too, in most cases.Remember, the sun will swallow the earth someday, so hold her and love her and affect change for the better sooner than later.

Urine is high in nitrogen and is perfectly fine to consume after having been turned into sugars and carbon by the metabolism of a plant.

Urine Gardening FAQ

Q: Can I do this with orchids?A: Absolutely. Dilute the ratio to three-quarters or half-strength (one part urine to 13 to 18 parts water), feed and make sure to allow nutrient solution to flow through the pot as opposed to pooling in roots/media, the same as you would for any orchids. I put my indoor orchids into the unplugged bathtub and feed to avoid overflows and sogginess.Q: If I water my veggies with urine, like you say, am I eating urine come harvest time?A: If you rinse, as you would for any produce, you’re following best practices. You are eating minerals that the plants have extracted from the urine, just as they would from soil, manure or petroleum-based nutrient sources. You really are what you eat.Q: What about the smell?A: A two-part answer: It won’t have a detectable odor any more than that store-bought, blue house plant food. Having said that, dilution is key with both. Some people look at the directions and think, “If a little is good, a lot is better.” This adage perfectly sums up the fine line going from nutrient source to pollution. The more accurate phrase would be, “If a little is nutrient, a lot is pollution.” Secondly, don’t save it up for later. Aside from starting to smell, the precious nitrogen your plants need will escape into the atmosphere if it sits for more than half a day. That would be that ammonia smell of old urine. Besides, you will make more pee, I promise.Q: How best do I “collect” my urine?A: First thing in the morning is ideal, as it’s the most mineral-rich. But any point is fine. Some find it easiest to pee into a watering can or plant pitcher with a wide mouth. With—how do I say it—certain “tackle,” the world is your oyster. And by oyster, I mean piss pot.Q: What if I’m on medication or supplements?A: The main precaution would be to avoid using urine from a course of antibiotics. Wait two weeks before feeding plants again. Antibiotics are basically a nuke bomb on the rich microbiotic life that is the biome of soil, turning fertility into wasteland.Q: How come dog pee kills lawns if urine is so good for plants?A: The “dilution is the solution to pollution” rule applies here. I could burn my name into your lawn like Fido with a strong solution of blue crystal miracle-stuff. Q: First you said that urine is safe and then went on to say that it’s a health risk in drinking water. Which is it?A: I love this question. Both, really. Urine, like any fertilizer, is high in nitrogen and is perfectly fine to consume after having been turned into sugars and carbon by the metabolism of a plant. “Uncut” nitrogen consumed by mammals starves hemoglobin in the blood (and as a result, the brain) of oxygen. Following that pattern, excess nitrogen in bodies of water causes algal blooms, which starve the aquatic ecosystem of oxygen and causes mass die-offs of micro and macro-organisms.Q: Why are you like this?A: I’m not exactly sure, but I am uncomfortable with the plummeting levels of biodiversity and the stability of the ecosystem as a result of slipping into the Anthropocene. For further reading, enjoy this rabbit hole of amazing data about using pee for good.

We Must Cultivate a Connection to the Natural World

I grew up in sunny, urban South Florida, with color and vegetation exploding at the seams. Sandwiched between the Florida Everglades and the Atlantic Ocean, the city that raised me is brimming with parrots, palms, hibiscus and tropical fruits.In the same breath, we sit at the forefront of the climate crisis. The beaches are not the same places that taught me the physics of sandcastles or how to treat Portuguese man o’ war stings. Instead, native vegetation has been removed, erosion has ensued, tides have risen and change proves itself once again as the only constant.Early on in my agricultural career, I began to realize not just how disconnected people were from their food, but also from themselves and their surroundings. Shifting circumstances seemed to arouse fear, instability, even abandonment. Farming was my framework for reorienting myself in an ever-changing world. It supported me in laying the groundwork on which to understand the importance of sustained health in myself and my community. All the while, the practice perfectly illustrated how everything is some kind of meal, feeding our minds and mitochondria, guiding me into a relationship with that which holds and heals.

Early on in my agricultural career, I began to realize not just how disconnected people were from their food, but also from themselves and their surroundings.

The Landscape Around Us Is a Living Organism

I, too, had been blind to the web of connection we are each so deeply woven into—the world of interdependence overshadowed by the story of the independent pioneer. At first, I found it hard not to be upset. The reality of understanding how many of these spaces are actually left to share, and who has safe access to experiencing them, highlights the trying balance of urgency and patience. Nonetheless, like the slow unfurling of a flower, it became clear to me how deeply our varying environments impacted wellbeing, from the individual to the collective. However uncomfortable, there is deep pleasure in lifting the veil of disconnection.Over the following years, I found myself farming in different parts of the country. Upstate New York was where I built my foundation in herbalism, where I fell in love with the wild and cultivated mint family, Lamiaceae (think mint, basil, oregano and thyme). They made my body feel alive. Northern California filled my eyes and heart with the golden hues of summers and sunsets, while my nose sought out the scents of dry heat, grass, eucalyptus and salt. Southeast Michigan taught me how to root, and provided me with nourishment through companionship. By growing crops like burdock, rose, elderflower and dandelion, I learned about the senses and energetics; bitter clarity, sweet protection and the umami of life. I often moved states with the seasons, snowbirding from parcel to parcel, chasing an endless growing season for a while. Then, I landed back in Miami. Revisiting the land that raised me was like settling back into a familiar hug from an old friend. Just like an old friend, time had passed, life had happened, we each stood with our own stories, the land holding eons to share. As I write this, I also want to explain why I have chosen to personify this place. The landscape around us is living. It is a multifaceted organism that has respirating, moving, living, dying, dynamic parts. It is a macro reflection of us, and we are a microcosm of them. As we step deeper into the pool of emerging tech, I hope humanity never feels so far from nature that we no longer recognize ourselves as a part of it. We are nature.

We are nature.

The Earth Is Always Changing, and We Must Bear Witness

As I begin again to work with the soil, so familiar and strange, I am often reminded of the variety of bugs, minerals, seeds and sediments, buried in this earth. Pushing back settled topsoil, the multidimensionality of every space, every moment, is revealed. This reflection acknowledges the same diversity in both myself and in surrounding communities. The planet feels exciting to come home to because it is always different. Just as there is an opportunity to be born anew in every moment, as we faithfully continue shedding skin and regenerating with each lunar cycle, we can too embody the new person already in existence without feelings of separation.The soil carries memories, holds bones, births flowers—is alive. In the humidity and heat of the South, things can change quickly. Imagine the heat generated from a compost pile and its ability to transform food scraps into rich soil in a matter of weeks. The climate acts similarly, embodying transformation. True to Heraclitus’ words, “All things flow, nothing abides. You cannot step into the same river twice, for the waters are continually flowing on.”There is courage in choice, and wisdom in acceptance. Like the seeds planted by our ancestors, may we continue to navigate an ever-evolving world with patience, resilience and care.

Bioregional Herbalism: How Learning About Surrounding Plant Life Changes Your World

Some years back, I received acupuncture from a rather knowledgeable man in South Florida for some nerve pain that was following me around. He proceeded to treat me, an experience that was peaceful and relaxing. So much so, that he fell asleep while the needles sat in my body. Maybe the chi flow had an effect on the practitioner? I coughed to gently awake him from his corner of the room, and he came to and pulled the needles out. I asked him if he used Chinese herbs for his practice, and he said yes. Excitingly, I asked him if he ever grew them, and, sadly, he said no. He had “never even seen what the plants looked like in their whole natural growing state.” The session ended and after a brief chat, we stepped outside of his home office and into his front yard. I immediately recognized a close plant friend, Sida acuta, commonly known as sida, growing wildly in his grass. “Doc! You see this one? This plant is one of Florida’s great herbal antimicrobials, one we work with for infections as well as for complaints of allergies for its cooling and soothing effects. Pounds and pounds of this are sent to the Northeast for folks who are dealing with Lyme disease…” His mind was blown. “Wow! In my own yard? A medicinal plant? I thought that was a weed!” “And what is a weed, then?” I asked him. “A weed is just a plant whose name you don’t know yet.” He smiled big and nodded approvingly of my main message: Learn your backyard plants.

Learn your backyard plants.

There Is Strength in Knowing About Local Plants

It’s common for all people to learn and study herbs and medicines that come from the other side of the planet without first knowing what is actually growing at their own feet. But let’s not stop in the backyard. There is a special spot that only a few know about. It’s called a bioregion, which is defined “not by political boundaries, but by ecological systems,” and thank goodness for that. Plants, although some may suffer at the hands of politics, which is deeply unfortunate, don’t know who you voted for. And, they probably don’t care. They are here to live and thrive and maybe even teach us something. So, why look at bioregional herbalism? There are a few considerations, one of which has been highlighted in our story above with the acupuncturist. The first point is that there is a strength in knowing where your plants are coming from. You know what soil it grew in; you know if there is a reason not to harvest from that spot because of pollution; and, on a lighter note, you have the connection for this plant’s purpose before it even comes out of the ground. It is a spiritual work at the end of the day. Another point is that the plants growing close to you are the ones you need. I can’t tell you how many times I have visited someone who was suffering from this or that, and—lo and behold—not even three feet from their back door was the herb that they specifically needed. I’m not even surprised by it anymore, as much as I respect it deeply. Let’s say that these plants have an affinity for their environment, obviously, and because you also live in their space, they can help you with afflictions that may arise in that same area. The last point I will touch on is that just because the herb you’ve purchased from some far-off place has the “organic” sticker stamped on it, doesn't mean that it’s authentic. The adulteration of plants is a huge deal, and it happens daily across the world. There are of course reputable and valued companies who hold true to their practices with integrity, but nothing will ever beat you going out and harvesting your own plants, period.

They are here to live and thrive and maybe even teach us something.

Identifying Local Flora Can Be an Enriching Experience