The Doe’s Latest Stories

I Used To Hide My Foster Kid Identity—Now I’m Embracing It

From the outside, I appear to have it all: A successful career, a stable, loving relationship, close family and friends—all the things that many people aspire to have. I seem to be a well-adjusted individual who leads a happy life with nothing serious to worry about. But that is far from reality. The truth is, I keep a huge part of my life firmly beneath the surface. In September 2004, when I was ten years old, my life changed forever. Along with my two younger siblings, we went into foster care. My parents had separated, and my mom was unable to cope with looking after us as a single mother due to poverty and ill-health. At first, we lived in different foster homes that were traumatic—far from where we grew up—before settling into one placement that lasted a year. As I navigated the harsh new reality away from my parents, friends, school and everything that I previously thought was my life, I went from being a carefree, happy child to feeling detached and afraid to speak to strangers. The only creative outlet I had to help express my innermost thoughts was through writing. It became a haven for me. I kept diaries confessing how I felt, how much I missed my mom and dad and how excited I was to see them next. But what also kept me going was having my siblings by my side, going through a shared trauma. Despite our young ages, we knew we had to stick together to survive.

The truth is, I keep a huge part of my life firmly beneath the surface.

My Friends Never Judged My Situation

In November 2005, we were fostered by a kind family that didn’t make us feel like typical “foster kids,” and I began to feel somewhat normal. A long-term placement, unlike our last, it was an environment we felt safe in. We were well-cared for, and for the first time in what felt like an eternity, I could finally laugh, smile, ease up. The protective shell that I built, allowing me to safely retreat into myself, had started to slowly become undone. I no longer felt terrified of my surroundings.When I started high school, I thrived—I made new friends and I enjoyed my studies. My school and home were far from where I grew up, so this allowed me to repackage who I was. Like a superhero, I hid my true identity, passing my foster family off as my own, projecting a different life against the one I was actually living. I didn’t tell anyone about my background for fear of being bullied and negatively stereotyped as a problematic teenager living in foster care. This constant worry led me to call my foster mother and father “mom” and “dad” whenever I mentioned my family or when I'd invite friends over for sleepovers. I continued this façade, repressing what I’d gone through for a while until I finally told my two best friends about everything. Instead of judging me, they reassured me that not everyone would react badly to my real life. As I progressed through school, I kept in contact with my biological parents. Education was important to them and they encouraged me to go to college. I always wanted to go, leave where I lived, explore somewhere different and take on a new challenge. I thought college would improve my life. I didn’t want to let what I’d gone through define my life and stop me from aiming high, so I decided to apply for degrees in English, with aspirations of becoming a journalist one day. I ended up being accepted into every university I had applied for; I knew many people in my position were not quite as lucky.

I finally feel like my authentic self and it feels liberating.

I Want to Help Other Foster Kids With Shedding Stigmas

After graduation, as I grew older, I continued to withhold so much of my past from people I met and became close with. I struggled with relationships for fear others would run from me, thinking I was damaged goods. But things changed in 2015 when I met my current boyfriend. At first, I worried about telling him everything about me. But I needn’t have worried. He was caring, understanding and someone who I could let into my life, flaws and all. In January 2020, at the age of 25, I finally sought therapy for the first time. Up until that point, for several years, I had experienced anxiety and depression due to repressing trauma and aspects of my life, without realizing how detrimental it was to my health. I felt exhausted living a double life and knew I needed help. As I began to open up to my therapist, it felt like a huge weight was lifted from my shoulders. At long last, I was able to work through the traumatic experiences that occurred in my life. Those sessions every Tuesday afternoon helped me more than I could ever imagine. Today, I continue to have a close relationship with both my biological and foster parents. I'm slowly starting to talk more about my past and no longer feel ashamed of it. If anything, I’m proud of my resilience and everything I’ve gone through. I finally feel like my authentic self and it feels liberating. In the future, I have plans to work with children and young people living in foster care who are going through the things I did and help them realize they're not a negative, outdated stereotype. Foster kids are so much more than that. We are human beings who are smart, loving and who can lead fulfilled, happy lives, just like everyone else.

I’m a White Teacher, Teaching Black History

The first day of any semester is always exciting. That’s when I get to begin telling the big stories of U.S. history to a new cadre of students. Not just any stories of U.S. history, either—I focus on African-American stories of U.S. history, especially the early parts, up to the end of Reconstruction.And I’m white.

Does that mean I’m incapable of telling the stories of other people in a historically accurate and empathetic way?

It’s Fair to Question White Teachers Teaching Students of Color

When I enter the room on that first day of class, I look out at the faces of my students, scanning them for looks of shock, surprise or dismay. I always assume my Black students will be skeptical of me, and I don’t blame them. We’re so accustomed to thinking of “ethnic studies” as the particular place of “those” people who are of “that” ethnicity that people’s surprise makes sense. My students whose lived experience has made them skeptical of a white man teaching African-American history aren’t wrong. I grapple with my place in telling stories that I find to be incredible, inspirational and definitional for our country. I am not Black, despite a smidgeon of African DNA, according to the National Geographic Genographic project, and I don’t live life as an African-American person. But does that mean I’m incapable of telling the stories of other people in a historically accurate and empathetic way? I know my students wonder that, at least sometimes.Since I continue to teach African-American history semester after semester, I clearly believe the answer is yes, although I’m always cognizant of how careful I must be in my role, and how I honor the stories I tell. I know my white skin gives me certain advantages and disadvantages when telling Black stories.A chance encounter with a former student gave me at least one validating answer to the question. And in that one answer, in that one conversation, I unpacked levels of something meaningful and beautiful, a sense that I can make a difference for my students of color by teaching how I teach, and also by consciously embracing who I am. This conversation also illuminated a sad reality for, potentially, many students of color.

My students know that I will work as hard for them as they work for me.

Running Into a Former Student Is Always Nice, but This Time Was Different

It was the first day of the fall semester at the community college where I teach. I had had to find parking in the student lot because the faculty lot was full, and I ended up—of course—having to park at the back of the lot. I got out of my car, slung my bag on my back and began striding across the parking lot. I cultivate that rumpled professor look, and by cultivate I mean that I wear linen pants, sandals in warm weather and comfortable t-shirts. Irons have not touched my clothes in years. I know that clothes can say a lot about a person, but I prefer to say it myself, to shout over my clothes. As I strode across the lot, I caught sight of a former student of mine. For the sake of this story, let’s call her Rhonda. It had been about a year since she was in my class, but I remembered her well. She was a student-athlete, so I had had to fill out several progress reports over the course of the semester in which she was my student. She’d also been a good student, which any teacher will tell you makes one stand out. Rhonda caught sight of me and approached. We exchanged greetings, and I asked how she was doing. I asked the regular professor questions: What classes are you taking? How’s the team doing this year? How close are you to graduation? She answered them all, and had, obviously, continued to do well.She asked me about the courses I was teaching that semester. Only two, I replied, because that’s all this school allows me to teach per semester (while packing 40 students into each course and underpaying me terribly, I might add). I let my students know about the low rate of pay because I want them to understand the reality of the situation of adjunct professors in academia. She expressed sympathy for my position, but I then explained that they have me stuck, because they know that I love teaching the courses I teach, so I’m going to keep doing it, as long as I can keep my bills paid well enough. There was a lull in conversation at that point. I assumed she was just contemplating the challenges of my adjunct life, but what was on her mind was more personal and more important.

Validation Is One of the Greatest Rewards of Teaching

Rhonda looked down for a second and then up at me and said, “Thank you. I really loved your class. As an African-American woman, I had never learned about myself. I never felt pride in who I am, but I learned so many things in your class that make me feel proud of who I am, proud to be Black.” I was stunned. Rhonda has always been an intelligent and thoughtful woman, but her words hit me with force. I felt proud, of course, but also sad. I couldn’t respond right away, but when I finally processed all that she had said, I answered. “This is why I do it,” I replied. “It really sucks that you have to wait until you come into my class to learn so much about your history and who you are, but better late than never. I love being able to teach people things they don’t know, and if those things let them see the reality of our country, then I’m doing my job. If I’m able to fill in a place that stood empty before, then I’m glad to do so. I just wish you had learned these things earlier. I wish that our school system taught us more, and helped more of us to see ourselves in our history.” I had to run to class, so I told her that she made my day, thanked her and reminded her that if she ever needed a recommendation, she could contact me. My students know that I will work as hard for them as they work for me. And that's why I do it.

How Twins With Different Skin Colors Perceive Racial Identity

“Dad, which box do I tick?” my brother asked when he reached the ethnic monitoring section of his first job application.“Which category best describes your ethnicity?” It’s an easy question for many people, but one that’s never sat comfortably with me, because I tick a different box from my twin brother. My brother and I were born in 1984 in Northern England and grew up knowing little of the Caribbean and Indian ancestry on our father’s side. I have blonde hair, green eyes and white skin. My brother has black hair, brown eyes and brown skin. It’s not something I ever remember noticing when we were young. My parents don’t recall any instances where we were treated differently. My mum said that if anyone commented on our appearance, it would only be to notice how much I looked like her and how much my brother looked like my dad.As we got older, we began to notice the evident surprise when people found out we were twins. It became a conversation starter, an interesting introduction when we met someone new. It was fun seeing peoples’ reactions. “Twins?! But you look nothing alike!”

I have blonde hair, green eyes and white skin. My brother has black hair, brown eyes and brown skin.

Growing Up, Being Mixed Twins Didn’t Seem Like a Big Deal

There were a few occasions over the years when, to our horror, we were mistaken for boyfriend and girlfriend. The only time things ever got truly uncomfortable was on a family holiday to Egypt in our late teens. My brother was so immediately perceived to be Egyptian that children spoke Arabic to him. Some teenage boys joked that we couldn’t be twins, and that my mother must have had an affair with a dark-skinned man. (My brother has darker skin than our dad, and when Dad’s hair turned grey, the boys were oblivious to their similarities.)We laughed off the comments, but it was an uncomfortable experience, particularly for my brother. It’s the only time he’s ever been singled out as different from his family. To me, that he should so readily have been identified as Egyptian demonstrates the problems of dividing people into categories based on perceived racial traits. While we never experienced racism growing up, we did at times encounter curiosity about our heritage. We were curious too. It wasn’t something our dad openly talked about when we were children. His parents divorced when he was three, and he never saw his father again. We knew our grandfather emigrated from Trinidad to serve in the Second World War. Our mum showed us photos of him in his Royal Air Force uniform, and of him and our grandma on their wedding day. Dad once met his grandmother, whose own mother was Indian and had traveled as a baby by boat from India to Trinidad with her parents, who tragically did not survive the journey, to work in indentured servitude. Our great-grandmother married a Trinidadian man, whose own father emigrated from Barbuda to Trinidad following the abolition of slavery, and they had several children, including our grandfather.

Our Dad’s Racial Identity Made More Sense Once We Met Our Grandfather

Our dad made contact with his father ten years ago after a friend researched our family tree and found him. He’d remarried and had more children. The reunion was no big drama, no tears or recriminations. His response to not seeing Dad for over 50 years was a shrug of the shoulders and a comment, “Well, I left you my telephone number.” The past didn’t really seem to matter. We were just one family meeting another family, curious to get to know each other.We got together with my grandfather a few more times over the years until he died. It was interesting to see the traits he shared with my dad. Both are charismatic, motivated and sometimes stubborn men. (Though, unfortunately, Dad hadn’t retained all his own teeth, which at age 90 my grandfather was very proud of.) My grandfather also identified very much as British and was adamant he’d never experienced any racism, a narrative that seems to echo my dad’s experience. Growing up in 1950s and ‘60s working-class Northern England, my dad has no recollection of ever feeling “other.” Much loved by the family around him, his mixed-race heritage was never a marker of identity for him. In his day there were no ethnic monitoring boxes to tick—he was just British.Both my dad and grandfather’s experiences may seem unbelievable from the outside looking in. There could be cases made for how their perception ignores the microaggressions perpetrated against them or the racism inherent in the systems in which they were raised. It could be argued my dad benefitted from the white privilege of his white family (though I don’t think anyone raised in 1950s working-class Northern England would describe themselves as privileged). Or you could say that my brother, our dad and his father before him succeeded in life despite their skin color. But they don’t feel that skin color has played a prominent role in their lives, and I don’t think their personal truths can be disregarded, or replaced by macro-level narratives that leave no room for their lived experiences.

I Hadn’t Really Thought About the Importance of Racial Identity Until Recently

So there are the “categories” of our ancestry: English and Scottish on our mum’s side and Caribbean, Indian and English on our dad’s side, yet a decidedly British identity for me and my brother. Our multihued family continues down the generations. My brother’s wife has fair skin and blonde hair and their son resembles her, whilst their daughter takes after my brother, with brown skin and black hair, though both children share the same beautiful brown eyes.Our identity has always felt tied to our family culture, rather than our ancestry. We didn’t pay much attention to our differences in skin color until the recent Black Lives Matter protests prompted discussions between us. Most importantly for me, I wanted to know if my twin felt he’d been treated differently to me on the basis of his skin color. He doesn’t. This is not to deny the existence of racism. I feel lucky that our family exists in a time and place where skin color hasn’t been at the forefront of our lives. I know this isn’t the case for everyone, and I welcome the recent resurgence of a commitment to eradicating racism in Western society.

Our ancestry has taught me never to judge a book by its cover.

Twins Born With Different Skin Colors Contradict Skin Color as a Determinant of Race

Where the current antiracist rhetoric fails me is in its divisiveness in its insistence that we set ourselves apart from each other on the basis of the color of our skin. For a family like mine, such reductionist narratives don’t fit. My twin and I are of the same “race”—all that differs is the appearance of our skin color. Yet current rhetoric would have us set ourselves apart from each other on this basis. I find it hard to understand why, in a progressive society where so many people clearly have a strong desire to eliminate racism, we continue to focus on the differences between us. People are complex, the world is complex and I can’t see how dividing ourselves into ever more definitive tribes on the basis of restrictive narratives will help our society reach a place where discrimination doesn’t exist. If you were here with me now, I would ask you to please look at me, then look at my twin. You may notice the differences in our skin color, but spend enough time with us and you’ll also notice our similarities: how we yawn the same way, stretch the same way, sneeze with the same annoyingly loud abandon (we get that from our dad). Whatever ethnic category box we do or don’t tick, it doesn’t really matter to us. They’re just labels. What matters is that we are a close-knit, loving family, aware of our rich and varied heritage, but not defined by it. Our ancestors’ indentured labor and slavery was barbaric, but it is also an immutable part of our history. Our family would not exist had the past not played out as it did.

Race Matters, but Skin Color Doesn’t Have to Be Part of the Conversation

Our ancestry has taught me never to judge a book by its cover. You can never really know someone unless you talk to them, but finding out about people is becoming increasingly precarious in a world where it’s so easy to offend.I will raise my children to be the change in the world that I want to see. I will teach them to recognize the privilege of their position in life, to equip them with a sense of justice and the courage to stand up to discrimination when they see it, but not to feel guilt for the whiteness of their skin—after all, their ancestors were slaves, too. To raise them to believe they are different from their uncle, their grandad or their cousin on the basis of skin color seems as ludicrous as ticking a different ethnic category box from my twin. It’s my goal to equip my children with an openness and curiosity about the world and everyone in it, to introduce them to a wide variety of cultures, people and experiences so that they don’t feel threatened by differences. I will encourage them to have compassion and empathy in their hearts, to have respect for their fellow humans and to listen to the stories of those they meet throughout their lives with curiosity and openness. It’s my hope that this will be a small step towards healing our increasingly fractured society.

I Wasn't Able to Say Goodbye to My Grandpa Due to COVID

My grandpa wasn’t ever just my grandpa. He was my mentor, my advisor, my friend and at times my jester. He taught me what unconditional love looked and felt like. He loved being around people and used each chapter of his life to help them in different ways, from building housing, temples and community centers to providing scholarships. A lot of what he did was about uplifting and building the community where he lived, whether it was in Fiji, New Zealand or Australia. Grandpa was the youngest of 12 kids in his family, raised with his nieces and nephews who eventually moved to different parts of America, Canada, New Zealand and the U.K. He was the superglue of our family, pulling us all together even when we didn’t get along. He passed away on Nov 22, 2020, after not seeing some members of the family for 12 months or more. COVID restrictions had prevented us all from traveling to him as we usually do. The death of someone like my grandpa shouldn’t be a reason for sorrow—he lived too amazing and colorful a life for that. But it was sad that he passed at a time when family and friends couldn’t be together, and when I couldn’t travel to Australia to be with them. So now we’re faced with the question, how do you celebrate an amazing man's life during a global pandemic? Our very 21st-century family found a bunch of ways to grieve and celebrate him, but I, his oldest granddaughter, can’t figure out how.

Saying Goodbye to a Loved One During COVID Is Hard for Everyone

My aunts and mum, who were able to gather in Adelaide, Australia during lockdown all got to spend time with him before he passed. They worked through 14-day hotel quarantine, hospital visit restrictions, police escorts and state border closures just to be there. My lovely aunts and mum would pass along all his characteristic one-liners to the nurses and grandma, as a way to assure the rest of us that he was okay. They mediated FaceTime calls for me so I could see him and talk to him and help him crack a joke or two. The rest of the extended family that wasn’t in Adelaide were stuck biding time until lockdown was over and we were able to travel there. This was harder than expected. Some of us distracted ourselves with alcohol, others with work, others by “socializing within limitations.” Those who weren’t in Australia called grandma incessantly for updates, sometimes a call a minute during waking hours, and she was completely unable to get downtime at home between hospital visits. The funeral that was organized was delayed a week while everyone in Australia waited for state border closures to lift so all the aunts, uncles, cousins, grandchildren and great-grandchildren could be together to mourn and celebrate my grandpa’s amazing life, albeit in a smaller way than we imagined.

How do you celebrate an amazing man's life during a global pandemic?

I’ve Tried to Grieve on My Own, but Can’t

Meanwhile, I was in San Francisco at home with my partner, who struggled to understand my connection to a man he’d never met and a relationship he didn’t share with his own grandfather. As you can probably tell, I was very close to my grandpa, as all his grandchildren were. To put it briefly, I have struggled. Traveling to Australia would have meant two to four weeks of quarantine, with no guarantee that I could come back into the U.S. for work, as I am on a visa. Moreover, I had started a new job supporting COVID-19 research as a lab-based scientist, and with COVID-19 cases in the U.S. spiking, time off was impossible. I had to put work before family, which meant missing my grandpa’s funeral. Two months on, I still miss the opportunity of being able to sit around and share stories about the glorious life my grandpa lived and how much love and goodness he shared with the world, and to simply exist in the same space that he recently existed in, something I will now never be able to do. I dream that every night I could smell his smells, feel his presence, watch his movies, eat his food, be in his garden and listen to his music. (He saved a list of songs on his YouTube account for me—the youth are not the only tech-friendly folks in my family). I wanted to join my mum, aunties and sister in carrying his coffin on its journey. My mum, grandma, aunties and sister still have not hugged me; I haven't hugged them. I cannot put into words how much I crave being in the presence of someone who really knew him, who knew his whole life like I did, if not more. Instead, I sit with my journal and try to channel my inner Jane Austen to work through what I miss about him in deep and entertaining detail. But I can’t even put my emotions into words, let alone deep or entertaining ones. Who do I talk to about this? My family in Australia have done their form of grieving. The family in the rest of the world was not as close to him as I am. I ran out of energy to navigate COVID-19, a new job and missing him, so two months on I’m writing this article, searching for advice, knowing there is no perfect answer. In the words of a close friend, “This is just how life happens. Fairness is not part of the equation.”

Not Getting to Say Goodbye to a Loved One Has Also Put Things in Perspective

COVID-19 has robbed me of precious time with loved ones, of my ability to grieve and celebrate their lives. Although it’s pushed me into valuable COVID-19-related research, it has also prevented me from doing the work I love, which is researching a cure for HIV. I have had to cancel numerous trips, both domestic and abroad. On the other hand, lockdown has brought many aspects of my life into clearer view. I lost my grandpa and had to prioritize work instead, but this is exactly what my grandpa would have wanted, had we all been thinking objectively: me supporting the wider community. I’ve connected deeper with family (and my weekly screen time has skyrocketed as a consequence). I couldn’t interact with friends, but I found a wonderfully compassionate man to share my life with. I couldn’t travel (and oh, how I miss it), but I found peace in my meditation and yoga practice, something my grandpa has been trying to instill in me since I was a teenager. My aunts, mum and sister carrying my grandpa’s coffin made me realize that my grandpa and grandma have raised two generations of strong women of color with diverse cultural backgrounds. What if I make this his legacy? A family of women who can share their strengths, weaknesses, love and kindness with other people, men and women alike. How do you teach people to be kind, share love and support each other when they haven’t had that modeled in their lives like I’ve been privileged to? Do we ask our leaders to step up? Do we create safe spaces for each other? Do we try to inspire each other so the strength of within is awakened?

He taught me what unconditional love looked and felt like.

The State of the World Right Now Is a Lot of Taking, and Little Giving

Grandpa would have said you can only share love and kindness, that there should never be any expectations of receiving anything back. What does that mean for our world’s healthcare workers, social workers, essential workers and research staff, who have spent the last 12 months inundated with COVID-19 and its effects at work and home? Many of us have had limited time off. (What’s a weekend again?) We’re consumed by the new information and the state of global politics, healthcare and travel. I’d like to say that I can turn off the news and have boundaries to how much COVID-19 information enters my personal life, but this is not true. After all, I missed the opportunity to say goodbye to my grandpa and support my family because of the effects of COVID-19. With the guidance of my grandpa, I’ve devoted my life to the service of others in different ways. Today I would like to ask you, the reader, how can you model love, kindness and community for yourself, your loved ones and the next generation?

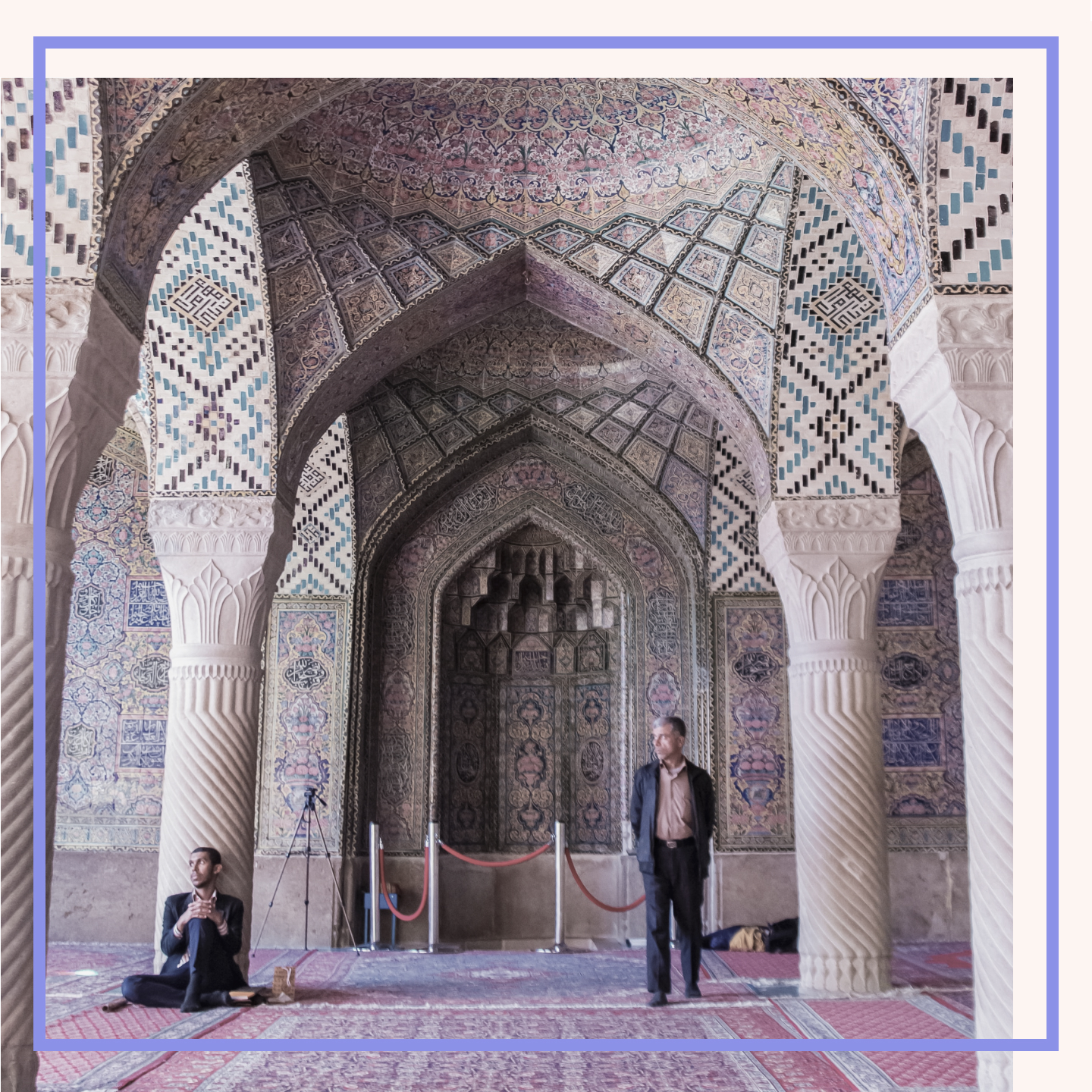

I Left Islam and Came Back Again: My Complicated Relationship With My Faith

I remember my first visit to Oxford University. I was only 16 and participating in an educational program at school. It was more than just a school trip to me though—it was a chance to finally be away from prying eyes, even if it was for a few hours. I could peel the layers of black fabric off my head, the black gown that isolated me so much from my peers. I could be me. I peered out from my seat at the middle-aged white man standing in the lecture hall. He was going to be talking about the Enlightenment in Europe. As he began speaking, I became enraptured. He discussed the ways that Western society shifted from religious ways of thinking to a more scientific approach to life. Religion, he told us, was a way to justify and understand the unknown in life. But science gave us real answers. Science and religion could never be compatible.For a split second, I wanted to put my hand up. I wanted to tell him that he was wrong. That there was a religion that corresponded with scientific principles. I wanted to show him that Islam was different. I almost had my hand in the air ready for a debate, and then it hit me. I was sitting in one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, and being taught by a lecturer who knew an infinite amount more about religion than I did. Maybe Islam wasn’t everything I had been taught. What if everything I knew was wrong? What if it all had been a lie?

My belief in Islam was damaged to the core.

I Was Isolated From the World

Coming from the highly religious background that I did, Islam was never a path I got to choose. It was thrust upon me in such a way that I never knew that I had a choice. Having grown up in London, one of the most diverse cities in the world, people find it hard to believe that I was ever isolated or removed from the bustling multiculturalism that characterized the city. I grew up somewhere in the middle of East and North London, where a small Muslim community exists. For 16 years, I spent my life gated in this little community. It was like a bubble. Muslim primary schools, Muslim secondary schools, mosques, halal shops and restaurants, women in niqaabs and men in thawbs everywhere. But between the hijabs and the topis (Muslim mens’ hats), I often caught glimpses of a world that existed outside these walls. Women who wore their hair out, state schools that were mixed, boys and girls walking hand in hand, mini skirts and jeans. Most of this I had seen already, on TV especially, but I couldn’t help feel a twinge of envy. I couldn’t help feeling, at 14 years old, that the scarf and abaya that I wore was weighing me down. Freedom was all around me, except in my own body. Everything was off limits. My dreams and ambitions were not befitting for a Muslim girl as my parents told me. Who wanted to see a lawyer in a hijab? Or a journalist? Or a presenter? I could never belong. Ever.I started to slip off the hijab whenever I could as I got older and started to venture out into the world more. I would leave the house, and in alleyways, libraries, public toilets, the back of the bus, I’d change into jeans, tops, dresses, skirts. I was a different person. It was exhilarating. Suddenly, I didn’t have to see the world behind slits. I could feel the breeze in my hair, the warmth of the sun on my face. I felt more in tune with the world in those moments than I ever had with the layers of black cloth that imprisoned my body. I was no longer a woman whose opinions could be assumed. I was a blank canvas, and I could be whoever I wanted to be. My words started to hold more meaning. People would listen to me more. I felt like I’d grown wings and was ready to fly. But as soon as I put the scarf back on, things would revert back. It was like being chained up. Wearing the hijab and abaya made me feel so visible but invisible at the same time. I was visibly different, but nobody wanted to hear my voice.

The Alt-Right Influenced My Thinking

So, when that professor at Oxford University explained the debate between religion and science, I was suddenly open to the possibilities. I had lived my life believing in the harmonious relationship between Islam and science. It confused me that this professor didn’t know it. If it’s so true that the Quran solved scientific conundrums that scientists were only discovering, why didn’t more people believe? Why weren’t the most intelligent people in the world Muslim? All of these questions, but nobody to ask. It was unheard of. I never knew it was possible to leave Islam. I didn’t know that there were other paths. That there were other possibilities. Even in the media, hearing about ex-Muslims just wasn’t something that I had ever been exposed to. So, I started to do a little bit of research and suddenly I found myself fascinated with talks by Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Neil deGrasse Tyson. People who rejected the notion of Islam. I felt so trapped in my home life that their words resonated with me. People like Harris and Hitchens were open to Muslims being profiled, stereotyped and treated differently. Why not? I thought, here I am in my own home, trapped by my family’s misogynistic views. Maybe they deserve that. My belief in Islam was damaged to the core. I can’t remember the moment that I left Islam, but I remember the feeling. It was like a weight on my shoulder had been lifted. I didn’t have to worry about provoking the wrath of the most unforgiving God. I didn’t care about going to hell anymore. I could go anywhere, be anything, be anyone. Except I couldn’t, because I was 16, underage and had an impossibly religious family.I started edging dangerously into alt-right territory, enthralled by the hatred spewed by Gavin McInnes, Lauren Southern, Milo Yiannopoulos, Rebel Media and so many others. These were the people who were exposing Islam for what it really was. My own brother had strangled me in my bed because I dared to disrespect him. I once wore a dress outside that my mother thought was inappropriate as it had slits on the side. Although I wore leggings, when she saw me walk through the front door, she grabbed the material and tore it off me as I was wearing it. My sister had called me a slut when she found out that I had engaged sexually with a guy. Amidst self-harm and self-hatred, I only found peace through channeling my pain into my anger towards Islam. It was the only way. I was trying so hard to escape Islam. The thing that I had grown up with. The very essence of it was so deeply entrenched in my identity, and it was exactly that I had to fight. I needed to sever its head before it ruined me. Being Muslim made me unpalatable to the Western eye so it had to be shed. It wasn’t until I started university that my views began to soften.

I ache at the thought that I’ll never truly belong with my family.

I Am Stuck Between Two Worlds

Studying English meant learning about colonialism, post-colonial literature, apartheid. Add that to being part of an extremely multicultural environment and I started to realize that my anger towards Islam was misdirected. The idea that being Muslim was unpalatable to the West didn’t come from my parents or Islam, but instead, it was a notion created by the West to “other” those like me. I started to appreciate my identity and the little quirks of having grown up in a Muslim household. I could no longer be the religious girl I was as a child, but I was starting to accept that I could never escape my Islamic identity because it’s an important part of what makes me “me.” Although I identified as an ex-Muslim for a long time, the rhetoric of people like Harris, Dawkins, McInnes and others is dangerous. If I hadn’t had my epiphany, my hatred of Islam could have boiled into the real world and who knows what kind of consequences that could have had. I’m more of a liberal, non-practicing Muslim now. It isn’t all sunshine and rainbows though. I ache at the thought that I’ll never truly belong with my family. I don’t wear a scarf or pray, or even believe in God. But I can’t express all of these things to my family. Somehow being in the middle, I can’t really be at home anywhere. In society, I can’t escape the remnants of my Islamic identity, and at home, I can’t be truly Muslim. I guess I’m destined to be stuck in this limbo. Not quite here, but not quite there.

Embracing My Muslim Identity in America Is Impossible

No one chooses to be here. I didn’t choose my race, ethnicity, family or my circumstances. What we do choose, however, is what to make of ourselves and how we’re known in this world. What I was taught is very different from what I believe is “America.” What I grew up living is very different from what many know. Living in the United States my whole life, I was told all I needed to do was dream and I could achieve anything. I am a half-Arab and half-Hispanic Muslim. As a young girl growing up, some people saw my multicultural background as a privilege, but throughout my years, my perspective has changed. I was taught early in life to be loyal to my country, believing we all had the same opportunity and hearing things like, “You can be the president one day.” How could I believe otherwise? The system I was taught states this country was built on “freedom of speech” and was created because others want to live freely and practice what they believe in. What if I told you that the same people that take pride in that belief, are the same ones who decide what is considered acceptable and what is not?I was also taught that you always speak out for the oppressed. It’s hard to know that there are people around you that would side with the oppressors. On the outside, people used to see America as a big melting pot, blossoming with different cultures, and considered it a blessing to be here. I, on the other hand, don’t see it that way. When I was younger, I took pride in being “American.” Now, it’s an embarrassment, a label I don’t associate with anymore. What I was told to believe and take pride in gives me nothing but utter shame. I saw the good, the bad and the ugly; the America I know is one many others never see.

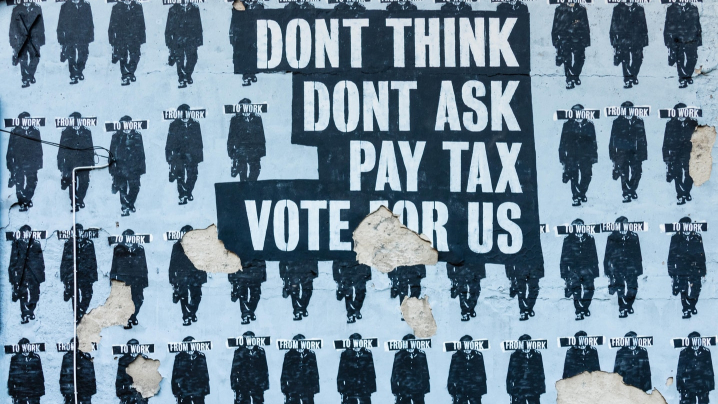

Living in the United States my whole life, I was told all I needed to do was dream and I could achieve anything.

How My Muslim Identity Crisis Began

My nightmare began when I was five years old. I grew up blessed with a mother and father who worked hard to be here and gave me and my siblings their best—from living in a safe area to going to the best schools. Most kids my age were all just trying to fit in. It was hard to believe that I went from hiding my ability to speak three languages to now solely speaking in Arabic daily. One day, I was awakened by bangs on our door and the screams of my mother begging FBI agents not to take my father away. Many people see the FBI as an organization that protects the United States, but I saw its agents as nothing but monsters who use citizen protection as a pretense. How can you enforce a law that you don’t follow?My father was asked about his opinion by a local newspaper regarding a recent scandal at a local mosque. In expressing support for a ruthless dictator to be overthrown, he unknowingly turned his and his family’s world upside down. The organization that prides itself in defending its country does more terrorizing than protecting. Targeting people based on their race and religion with nothing but stereotypes as justification is despicable. The beauty I used to see in this country left in front of me that same morning. Using someone’s religion against them in a country that prides itself on its “freedom of religion” is hypocritical. That my father’s religion makes him suspected of being a terrorist sympathizer shows the bigotry that is very much alive in this country.

I began to see this country for how it treated people like me.

America Wants Muslims to Suppress Their Cultural Identity

Growing up post-9/11 was hard on me. My father being attacked because of his religion, which is mine, too, was the most painful experience. Being dragged in a legal battle for 13 years to plead why a father shouldn’t be deported and taken away from his children is indescribable. Going to a primarily all-white school, as great as it might’ve been seen opportunity-wise, was torture. The news constantly changed the people around me, and it hurt me more than ever. Once taught to embrace religion, I felt as if I was embarrassed to be Muslim. I was called a terrorist, a towelhead, Osama bin Laden’s daughter. I didn’t let it break me, and I had to keep it together. They constantly told me I didn’t belong here, as if I didn’t know that already. They destroyed our countries, and when we seek a better life, they ask us why we’re in “their country,” which their own ancestors fled to.I began to see when people became heartless. I began to see that the place in which I grew up was not the place that I currently saw. I began to see this country for how it treated people like me.When did we let hate flaw our judgment? I don’t belong where I was born. I don’t belong where I am from. The place where I grew up, my home, has criminalized my race and my religion. Everything that I identify as is a threat. Americans claim to uphold “land of the free” values, but I feel like I am in shackles, afraid to be judged and lose out on opportunities just for being different.Years later, I have grown past the embarrassment and embrace what I am. No one is going to put me in a box. I was taught to embrace being an “American,” but what does that mean?

I Cleaned Up My Community and Answered an Ancestral Calling

After a decade of working my way up the Madison Avenue ladder of success, I told myself that it was time for me to vacate my comfy corner of corporate America and enter the "real world" to make a difference in people's lives. The summer of 2015, I found myself in a small dejected city in New York’s Mid-Hudson Valley. A city often referred to as a war zone. As I laid in bed, I could hear the sound of bullets echoing through the night. This city was a hidden gem that had deteriorated due to decades of neglect and crime. I witnessed firsthand the despair that imbued every corner of the city. I learned from speaking with people in the area that this place I now called home was a dumping ground. People there had come to believe themselves to be trash, and over time, began to adopt ways of treating themselves and each other as such.After a couple of years of living there and participating in some neighborhood cleanups and revitalizations, I decided to create my own initiative. I endeavored in building a community green space with the intention to bring hope and joy to this dying place. My plan was to clean-up and establish this new space on the abandoned lot my siblings and I inherited from my mother after she passed away.

I was filled with doubt.

I Witnessed a Cycle of Brokenness

This decision and process ignited an inner struggle and many questions. I found myself wondering why people piled unwanted things here and how the habit begins. It seems to start with little things—broken fences, cracked windows, overgrown grass and one or two scattered discarded items carelessly thrust on the grounds. When people walk by they slowly start adding to the brokenness and the cycle goes on and on. As more and more people dump their trash in the space, the space becomes the place where all the unwanted things go, it's a graveyard for everything broken. No one considers it their “responsibility.” This becomes an endless cycle. Rumi states, “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right doing there is a field. I'll meet you there.” The once abandoned lot became a special space beyond judgments and ideas of what was right or wrong about our community. I had moved beyond my own judgments and prejudice about this place and the one thing that pulled me away from these distractions was my pure intention to surrender to the need of my community for a safe place to gather and heal. At first, I was reserved and sometimes even resentful of all the work and degree of time I was dedicating to the vision. I saw that even though I was committed to doing what needed to be done, my heart was not yet completely in it. I was filled with doubt and regret. Flashbacks of the comfy life I left behind filled my mind and, suddenly, I would return to the reality of what seemed like a never-ending mess. I eventually realized that the only way to make this dream a reality was to completely dive into the mess. At this point, there was no turning back.

Our Work Helped Mend the Community

When one person decides to surrender themselves to the greater good of the community, others eventually join in to help. What was built, I could never have done it alone. It took a diverse group of ever-changing faces with a shared commitment to make good things happen.The more committed I became, the more we grew in numbers of committed dreamers. Over time, magic began to happen. Our community began to forge a new relationship with the earth, and along with it, a growing sense of responsibility for it. Collectively, we began to break a cycle that felt like a generational curse. Little by little, the work of one was made light by the hands of many.Those days filled me with joy. Some of our greatest moments came from getting the youth involved and teaching them how to use garden tools. Many kids had never used them because they lived in buildings and had no access to green spaces. The work we were doing was impacting the people in the community. When one of the kids broke the lawnmower we were using for the cleanup, a good Samaritan who had learned about the work we were doing sent us a check so we could replace the broken machine. It was happening: People from the greater community began to show that the work we were doing mattered to them.The cleanups continued for two summers and paved the way to a community festival. This proved to be an important and much-needed opportunity for people to come together and demonstrate collective care.

Each one of us has a role to play in making the world a better place.

I Felt Closer to My Grandfather By Cleaning Up My Community

These experiences taught me that people have a deep need to be recognized as worthy of being invested in. I didn't have much, but what I had I gave. I believe that this is the way that our world will change. We benefit from acknowledging that we all are living on the same soil, and every community is sacred ground. Cleaning up began with heaps of garbage and ended with a healing green space and a community festival that united our community and inspired them to imagine new possibilities. This journey helped me weave a new ancestral narrative. Although I have no kids of my own, in ways, I adopted the kids of Heartbrooke Street as my own. I especially connected with a bright young boy who showed much promise. I found great joy in listening to Jay’s dreams for the future and his enthusiasm to help build a community labyrinth. It was inspiring to witness his commitment to teaching other kids how to appreciate and participate in this newfound sense of a united community. That summer, he became the son I did not have.Perhaps the desire to make a difference was deeply embedded in my DNA. I had grown up hearing about my maternal grandfather, Papa Louis. At a time of great need in Nigeria, he played the pivotal role of supplying essential resources and infrastructure to the Igbo community, before, after and during the Nigerian-Biafran War.It was as if through service to the land, I answered my ancestral calling, my role and contribution toward the great healing and wholing of planet earth. It was said that anyone who showed up at Grandpa Louis’s doorstep requesting support would receive a place to sleep, a job and food for a year so they could move forward. He played his part to help his community move forward, and I feel grateful that I played mine in my own village in Upstate New York.Each one of us has a role to play in making the world a better place. I hope that we all find a patch of forgotten soil, a space that challenges us to dig deep, grow and remember.

I Learned About Having a Healthy Marriage Through My Parents' Love Letters

How do you define love? I define it by the example my parents set. My brothers and I grew up in a home where we were witness to two people who prioritized each other’s well being above their own and continually demonstrated affection and respect for each other. That kind of love is not as ubiquitous today as it should be. The world we live in can be overly stimulating and leave many with little time and/or motivation to cultivate and nurture profound and epic love for their partners.My parents' love developed and deepened through the written letter, a form of communication that is practically non-existent today. Letter-writing offers a way to express our sincere emotions and our real vulnerabilities. For many, it is easier to write down their thoughts than to say them out loud.

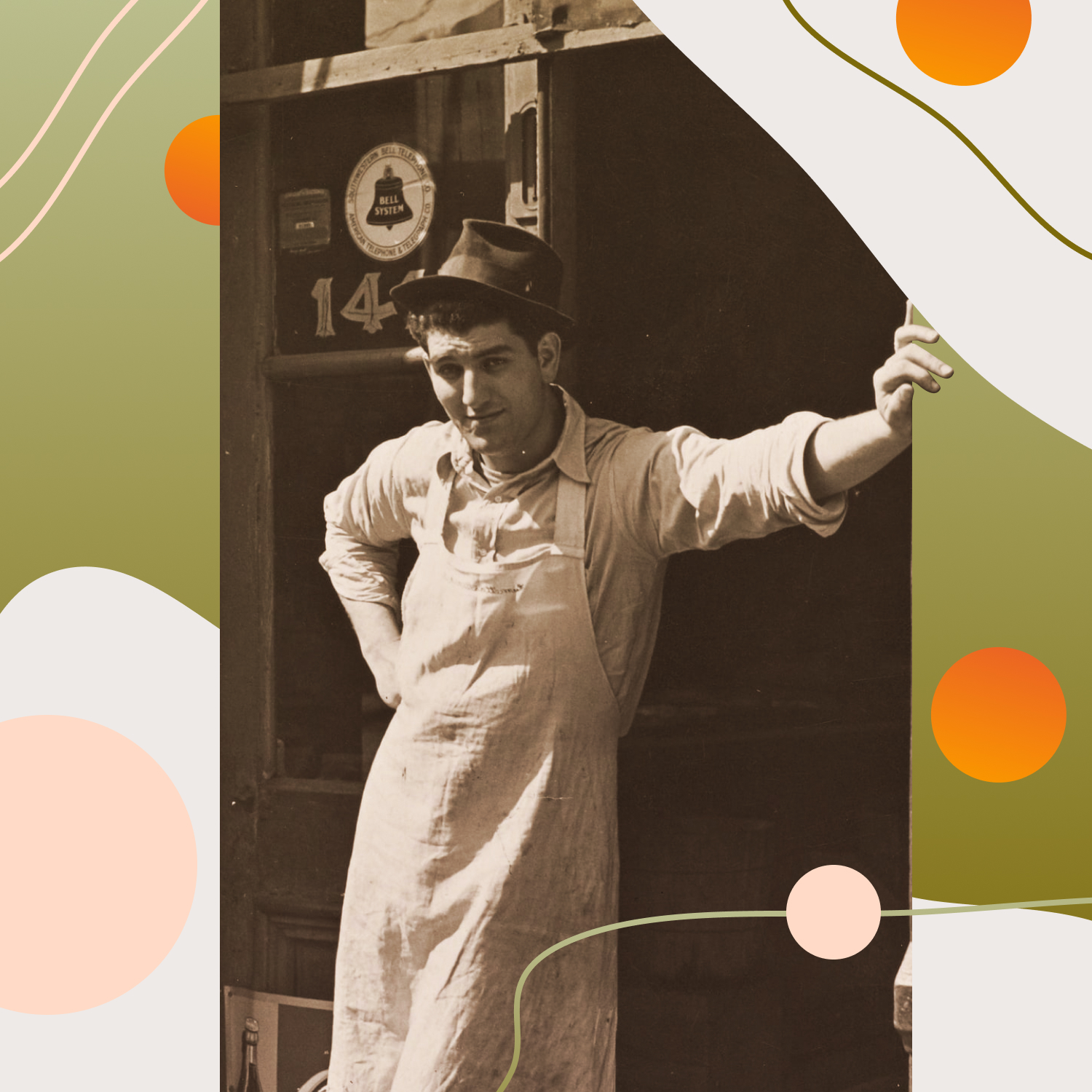

How My Parents’ Relationship Began

My parents met in 1945, when my dad, Abe, and my Uncle Hal were Coast Guard buddies stationed in Greenland. Hal had married my mom’s sister, Rae, during his service in WWII, and they traveled together until she became pregnant, prompting Rae to live with my mother, Dotty. Hal got to know my mother when he visited Rae on his leaves and eventually decided to bring my dad with him on a subsequent visit. Abe and Dotty had an instant attraction to each other and went on several dates whenever dad had leave. Though Dad lived in Philadelphia and Mom lived in the Bronx, they continued pursuing their courtship. I sometimes wonder if they considered the ramifications of the “geographically undesirable” aspect of their relationship, or if they were living in the moment, simply enjoying each other when they were fortunate enough to be together.Eventually, Dad completed his service and he and Mom began the next stage of their courtship. In Mom’s autobiography, which she wrote for her children, she remembers, “Abe was clean-cut, on the quiet side, and a perfect gentleman. After his discharge, he made every effort to visit me as often as he could. He would take the train from Philly to Manhattan, and then out to the Bronx, where I lived.”

My father wrote letters to her every single day.

Long-Distance Love Letters Is How They Stayed Connected When They Were Apart

This became a challenging routine and they needed to stay connected in between visits. In 1946, there was obviously no email, texting, Facetime or Zoom. Even a long-distance phone call was considered a luxurious indulgence. Their best and only option was snail mail. My father wrote letters to her every single day that they weren’t together. My mother wrote daily as well.“He wrote such nice, loving letters with cute little drawings around the margins,” she remembered. “He courted me for a while in this way; that is, in person and by mail, and we ultimately became engaged.”Mom saved all of dad’s letters in a floral cardboard, octagonal box. Tragically, he passed away at the too-young age of 43. My mother remarried a few years later, and when she did, she gifted me dad’s collection of love letters. I never opened the box. Well, in truth, I did just once to look at the letters and touch them. They were all in their original envelopes but I didn’t open them. I considered them sacred documents that didn’t belong to me.

I Made Sure the Legacy of My Parents’ Love Letters Lived On

My stepfather passed away 25 years after marrying my mother, and I tried to return the letters to her then. Dad was always the love of her life, and I thought they should be in her possession. She told me to keep them, so I did. I realized these letters were a treasure for our family and years later, she allowed me to publish a book from these letters, and I printed a copy for each member of our family. Of course, I made a copy for her as well. Each of their three children and four grandchildren received copies as well.I felt privileged to peek into the lives of my parents as they developed their romance. My dad had a fabulous sense of humor and it showed in his letters. For example, one of his early letters closed this way:As ever,Sincerely,Yours trulyRegardsLove (ahem!)Aw skip itAbeAs I mentioned earlier, they corresponded daily, so my dad’s letters were filled with the details of his daily life, one that looked very different from ours today.

Their legacy is with me.

What I Learned About My Parents Through Their Letters

I also got a taste of how they spent their time together. He wrote about wanting to sketch her profile on his next visit but wondered if she’d be able to sit still for 30 minutes. He expressed his doubts. “But if we keep the rhumbas and the sambas off the radio, you might be able,” he wrote. No date night Netflix or video games; instead, Latin dancing for Dotty and Abe!My father was a percussionist and loved music. Many of his letters revealed his musical interests. “My sister bought a phonograph last week and we’ve been buying records galore,” he wrote. “I looked high and low and finally got my favorite two records and keep playing them whenever I’m home. One is ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ by Benny Goodman. The other is by Bunny Berrigan called, ‘I Can’t Get Started With You.’ Both terrific. Did you ever hear them?”Although there is a renewed interest in vinyl records today, generally speaking, phonographs and vinyl have not quite replaced the more convenient and universal musical services such as Spotify. There was also a huge disparity in the postal service then and the postal service today. In one of the letters, my dad expressed his disappointment in not receiving my mom’s letter that morning. But he didn’t despair because “maybe it will be in the mail this afternoon” he wrote. Imagine that—two mail deliveries a day.

The Letters Helped Me Understand What a Healthy Marriage Looks Like

Sadly, the letters my mother sent my dad are long gone. Nonetheless, I was able to learn much of what she wrote through my dad’s responses. It is with great privilege that I had the opportunity to discover, and share with my family, the history of the love affair between my parents, who I miss deeply each and every day.But their legacy is with me. They showed me and my brothers what a loving marriage looks like—not by words but by comportment. Theirs was a union of great love, devotion and mutual respect. Today, I am blessed to be in a loving marriage, and I thank Mom and Dad for their example.

I'm Learning a Niche Language to Talk to Family I've Never Met

When I was young, my father used to thunder up the stairs towards my room, chanting a variation on the famous refrain from “Jack and the Beanstalk”: Fi, fie, fo, fum, I smell the blood of English, Irish, French, Finnish woman. That usually meant I was about to be tickled or, less fun, made to put on shoes and go somewhere I didn’t want to go. It also meant that I knew from a pretty young age who my grandparents were: I was a quarter English, a quarter Irish, a quarter French, and quarter Finnish. That was pretty cool because I liked Ireland a lot. I never thought too hard about the rest of it.There are some things you learn about your family as a child that you just accept: My uncle was killed by a car at 19. My grandfather was an alcoholic. I have a large extended family in Finland, but we’ve been estranged since the latter half of the 1910s. You know, normal things.My relationship with my dad’s family has always been patchy to begin with. Of his four living siblings, I’ve only seen two of them since I was old enough to form coherent memories. My grandmother was the child of two Finnish immigrants to the United States who met at a Midsummer dance in Kaleva, Michigan, in the early 1900s. Her mother’s name was Helmi. Her father died of black lung. That’s all I know.

Like every other person on the planet with too much time to kill, I’ve picked up a language during quarantine.

Exploring Your Roots as a White Person Is Complicated

So, full disclosure: I’m a white American “reclaiming my heritage.” If that makes you roll your eyes, don’t worry—it makes me roll my eyes, too. That’s the quintessential white American thing to do, right? Tear millions of people away from their culture and heritage for hundreds of years, then turn around and gush to all of your friends about how your Ancestry.com results came back 15 percent German?(On an unrelated note, Ancestry.com tells me I’m related to Emporer Nicholas II through my great aunt.)When you grow up with no culture but the dominant one, there’s something seductive about The Other, about a shared identity based on shared history, and not just the fact that I watched the same obscure early-2000s PBS Kids cartoons as the rest of my white American age cohort. It’s almost trendy.So, like every other person on the planet with too much time to kill, I’ve picked up a language during quarantine.You might think that’s admirable; you might think it’s self-serving. Mostly, the Finnish people I’ve talked to think it’s flattering, if a little confusing. Why would I want to learn Finnish? It’s hard, hardly anyone speaks it, and all the people who do speak English anyway.

What I Get Out of Learning Finnish (Besides Speaking Finnish)

Miksi kielemme? Älä ymmärrä meitä väärin, mielestämme on hienoa opiskelevasi sitä, mutta…miksi? Why Finnish?Well, I could say—in English, because I’ve only been doing this for nine months and I still trip over my words—that I think it’s a cool language. It’s not even part of the Indo-European language family, so it’s totally outside my comfort zone, linguistically. I think the country is beautiful and I’d love to visit someday; and of course, I have some family there.And that’s all true. Finland is beautiful. In October, when all the leaves lining the streets of Helsinki are brilliant yellow and the sun sets at 5 p.m., it reminds me of my own home. It reminds me of myself, quiet and introspective, with its five million citizens and two million saunas.Finnish is a cool language. It’s like a puzzle, and I love puzzles. It’s not as hard as people say it is, either. Just like English speakers, Finns are quick to say their language is the hardest in the world to learn, even if there are parts of it that make perfect sense to me.And I do have family there. I met a second cousin once who spread a massive family tree out on the table of a pizza place in Helsinki to show me dozens of distant relations with names I couldn’t pronounce at the time. I can pronounce them now, and surely that’s a good reason to learn a language, right?But those probably all sound like excuses. Even to my ears, they ring false. We white American liberals have all spent the past four years idly daydreaming a way out of this, some social democracy fantasyland to welcome us with open arms in our righteously privileged flight. Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a country that wanted us, who saw us not as Americans but as members of the family who have just been estranged for a little while?

Finnish is a cool language. It’s like a puzzle, and I love puzzles.

Learning a Language Helped Heal Old Family Wounds

My great-grandmother left Finland for a better life in America, while her sister stayed behind and never spoke of her again. It feels a bit backwards to say that I have any legacy, any connection to the country at all, when she gave it up and her sister renounced all ties.I feel silly saying this to people who look at me and see no connection to themselves, to whom I’m just another American playing at being something else. But the truth is that I own a small baby doll wrapped in a reindeer-pelt parka that my grandmother bought for me in Lappi the one and only time she visited Finland, when I was too young to know what “Finland” was, long before I learned to recite “English, Irish, French, Finnish woman,” and even longer before I knew what it meant. Just before she died, she told me that she’d memorized “Silent Night” in Finnish and always tried to remember, but that lately she couldn’t.Or there’s the truth that my father, who I have only seen cry one other time in my entire life, wept when he heard my high school choir sing Sibelius’ Finlandia, because he had lain on the living room floor and listened to that record on repeat as a boy, the single piece of his grandmother that he had. In a perfect, pandemic-free world we would spend his 70th birthday in Helsinki next year and walk beneath the yellow trees. He can’t speak a word of Finnish beyond “thank you.” (Correction: He would like me to say that he can also say sisu.)I have no connection to Finland. In the end, I’m American through and through, and no language I could learn is going to change that. But to my father, who grew up yearning for a culture and a history he could never have, or to my grandmother, who gave up hers to please an abusive husband, I was and am the link they were missing.Why Finnish? What’s so special about Finland?That is.

I Reclaimed My Grandparents’ Polish Citizenship to Move Overseas

I’d been staring at the yellow Post-It the entire evening, trying to get my head around what I’d just scribbled down. Considering how agonized I’d been about making the phone call for the last couple days, the conversation with the polite yet detached woman at the Polish consulate seemed a bit too straightforward, almost clinical, as if she doled out the same advice 100 times a day. All I’d done was “press 2 for the citizenship department.” Suddenly, the door to Europe had creaked open just enough to get my hopes up.The list of emigration requirements on the Post-It was indeed daunting, though there was also something mildly reassuring that the task had some scope around it now. But even the first requirement on the list—“original birth certificates”—might as well have said “learn how to walk on the moon.” Simply put, they both seemed equally impossible, and I was going to need a lot of help figuring out where to even begin. So I walked into the kitchen where my parents were enjoying their customary pre-bedtime snack, took a deep breath and let the words spill out. “Hey Dad, you know the whole thing where your parents went through unspeakable horror and tragedy at the hands of the Nazis? And then they met each other in a displaced person’s camp in Germany after the war where they had you, and then came to America to give a better life to their children but were completely shattered by what they’d lived through and never really healed? Yep, that thing. Well, how would you feel about me taking advantage of their hardships by reclaiming their Polish citizenship in order to realize a lifelong dream of moving to Europe?” Needless to say, my dad turned his attention away from his bowl of Honey Nut Clusters. He wasn’t offended by this pipe dream (which had been my primary concern), but actually appeared intrigued at the opportunity to learn about his own past while helping me in the process. After all, they must have known I was going to make a push to get across the ocean at some point. Ever since falling in love with a Swiss-French girl (and her language) at the tender age of 11 while on an exchange program in Newcastle upon Tyne, there was a strange magnetic force pulling me toward that part of the world. There’s no way Bernadette could have known how her thick accent and blonde curls had changed the trajectory of my life, but I suppose we never really know who we’ve impacted along the way. For all I know, I’m somebody else’s “Bernadette.”

Thus began a four-year journey.

Obtaining an International Passport Is a Long Process

And thus began a four-year journey to fulfill all the requirements on that little yellow Post-It. Quite the journey it was, too, full of byzantine processes, linguistic minefields, countless dead-ends and invaluable assistance from unexpected sources. Here are a handful of highlights:

There's a lot of talk about how to be a good ancestor, about the choices we should make that might one day benefit those who come after us.

I Wonder How My Grandparents Feel About Me Claiming Their Citizenship

I gave up a number of times over the four years, but the dream of getting to Europe proved too strong and I was always lured back into the application madness. It even became a bit of a joke among my friends: “So, are you Polish yet?” Eventually, I got my big break thanks to some documents unearthed in an obscure Jewish historical database in Warsaw, definitively proving my grandparents’ Polish citizenship. I finally got my hands on that spectacular dark red passport at the end of 2015, which I used to move to London in April of 2016. And while I absolutely miss my family and friends back in the States (as well as easy access to slices of New York pizza), London has been extremely good to me. I met my wife here, have made some wonderful new friends and have been able to continue my career in the “Big Smoke” without interruption. I often wonder what my parental grandparents would think of all this. I should note that I never really knew them. My grandfather, Leizer, passed away shortly before I was born, and while we visited my grandmother Minna in her retirement home growing up, her mental health had suffered so greatly from her life experience that she only spoke a few words of Yiddish and didn’t even recognize my father toward the end. But beyond lacking any substantive relations, I also don't speak their language and don't practice their religion. So, would Bubby Minna and Pop-Pop Leizer be upset that I've essentially taken advantage of their trauma to chase after my own desires? Or, would they approve (or even understand) that I've had a life well and fully lived, that their son was a wonderful father who gave me plenty of advantages and that I fought through all those hurdles to get my hands on the passport which would open up an entire continent thanks to Schengen?

This Experience Has Brought Me Closer to My Polish Ancestors

There's a lot of talk about how to be a good ancestor, about the choices we should make that might one day benefit those who come after us. But what does it mean to be a good descendant? Keeping certain traditions alive? Which ones? If I peeled back another layer of my own emotional onion, I suppose the scarier but more pointed question is this: If I knew my ancestors were disappointed because of what I’d taken without giving back (in their eyes), would I care enough to change? I hate to admit it to myself, but I honestly don’t know the answer to that.The distance I’ve placed between myself and my family’s cultural and spiritual history has been a common and often tense topic of discussion with my parents over the years. And it’s not something I necessarily hide either. Case in point: My wife just asked me the other day, completely unsolicited, why I appear to be so interested in cultures, languages and customs other than my own? I have my thoughts on what has contributed to this, but the likeliest answer is that it’s just the way I was made. Interestingly enough, the whole Polish identity experience has actually brought me closer to my grandparents. I think about them and what they went through quite a bit, and how it helped me get to where I am. And even after almost five years in London, I often find myself smiling while walking down a high street or into a pub, almost like I’m walking on air, as if the force of gravity isn’t quite as severe on this side of the ocean. Maybe I learned how to walk on the moon after all. And I still have that yellow Post-It. I take it out every so often just to remember what it was like to write that list of impossibilities.

What Americans Can Learn From the Immigrant Spirit

"Nearly all Americans have ancestors who braved the oceans—liberty-loving risk takers in search of an ideal—the largest voluntary migrations in recorded history…Immigration is not just a link to America’s past; it’s also a bridge to America’s future.” – President George H.W. BushAs I sit here with my COVID-19 mask collection, I am thinking about my dad’s parents. They are long gone now, but they shared critical stories about their past lives in Eastern Europe. After the horror and suffering they faced in the infamous “pogroms” in Russia and Ukraine in the early 1900s, it was no wonder they were so happy, relieved and proud to arrive in the U.S. to become citizens. A Google search informs us that a pogrom was “an organized massacre of a particular ethnic group, in particular that of Jewish people in Russia or Eastern Europe.” My grandmother had nightmares about these organized attacks for her entire adult life. Hiding in a haystack as a teenage girl so as not to be raped or have a hand chopped off is not something anyone born today in the U.S. can identify with. My grandfather had scars up and down his body, sides and forehead from the Cossacks, who used the blades of their swords to slice him up. His four-foot, 11-inch sister dragged him home and saved his life. Another time, he was visiting a nearby town to get supplies and was advised not to return home that day. He slept that night in a shed with cattle. The next day, when he arrived at his home on the Ukraine-Russian border, he found a few dozen dead folks from his village, including their rabbi. He and a few others dug graves and said their prayers.So, it shouldn’t be a surprise that they eventually left their homes, and somehow, around 1918, were fortunate to be included with a large group of refugees on a voyage across the Atlantic riding in third class to Ellis Island. Thankful to arrive in America, they had no food stamps, no welfare checks, just Brooklyn and Lower East Side tenement walkup railroad apartments with no air conditioning and no refrigerators. Every man for himself to find a job and stay alive. They worked their asses off for the next generation. My grandfather became a baker on the night shift—he worked for the union for almost 50 years, and with his small income as a baker, he could afford to send my dad to medical school in Europe.

Those bullies never bothered me again.

Racism Against Immigrants in America

When my dad was growing up in the 1940s and 1950s in the Northeast, there weren’t any pogroms, but there was still racism by so-called "original whites” against the newer immigrants. These newer white immigrants—Italians, Jews, Irish—were also excluded, along with Black, Chinese and Hispanic people. These “lesser” whites could not buy a home in “originally white” neighborhoods, had no access to loans, were excluded from clubs and life was confined to the parameters of their own neighborhoods.In my dad’s Class of 1948 high school yearbook, there were photos of all races and religions at that time. They shared the same classrooms and teachers—a living example of Martin Luther King Jr’s "I Have a Dream" speech many years later. Yet when school ended, they all headed to their ethnically-separated neighborhoods. For the most part, their social lives rarely overlapped, although my dad did have a few friends from various ethnic backgrounds. Twenty-five years later, I was growing up in a nice suburb of Manhattan with a fine public school. The racism I experienced—occasional name-calling from a select group of bullies or perhaps getting punched while walking to school—was so very mild compared to what my grandparents faced. I knew what my grandparents had endured so I brushed it off. In seventh grade, at the advice of my grandfather, who heard my story about being bullied, I carried a baseball bat with me to school. The bat moved with me from class to class. I took a few swings in the air to send the bullies a signal when I spotted them down the hall. Surprise, surprise—I was called to the principal's office and questioned. I told them my situation, and they said, “Okay, just, please don’t bring it tomorrow!” Those bullies never bothered me again.

Queens Is the Standard the Rest of the Country Should Strive for

I recall finding the original 1950s deed for our home from the previous seller. It included a covenant barring the sale or rental of the house to non-whites and people of Jewish descent. (A U.S. Supreme Court ruling held such covenants unenforceable in 1948.) Despite the clause, my parents purchased the house, and over the years our village became more ethnically diverse. There are now many places in the U.S. where the minority population now has a majority. The phenomenon of an ethnically-clustered community is not necessarily a reaction to racism or intolerance. Instead, it’s a natural desire to live with like-minded people that share a common language, culture and tradition. Birds of a feather flock together.Although many of these ethnic communities remain, Queens, New York, continues to break this pattern. In 2018, the borough’s 2.29 million population held the world record for the most diverse human population on the planet, representing more than 138 nationalities and languages. All these unique individuals live together in peace 99.99 percent of the time. As you explore the streets you notice that every few blocks, the languages on the storefronts change along with the variety of produce and foods. Unlike the 1900s to 1980s, it’s normal to witness biracial couples walking hand in hand in the streets—a real example of America as a “melting pot.” It’s a place where people are valued by the “content of their character,” unjudged because of the color of their skin.

The call of the time is to connect to ancestors.

What We Can Learn From Immigrants Today

As a child, I grew to love Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches, and by the age of six, I had entire portions memorized. Perhaps these speeches informed my decision to become an immigration attorney. Or perhaps it was my Swiss grandfather who unknowingly piqued my interest. I was 13 years young when I visited Geneva, Switzerland, to spend time with family. One afternoon, my grandfather (who had fled the pogroms in Poland) explained he had once sponsored refugees for “visas'' to be temporarily housed in refugee camps in Switzerland—they were Jews from Poland who escaped Hitler and the death camps. I asked him about visas, and today they’re how I make a living. It is sometimes funny how synchronicity works. Years later, I told my Swiss grandfather about a man from Geneva living in my Manhattan building. I told him the name and seconds later replied. “I sponsored his grandfather.”For the past 25 years, I have assisted many people from all over the world to achieve their own "American Dream.” Despite the hate-filled narrative— propagated by the news outlets, social media and colleges—that half of Americans are racist and sexist, the truth is, most people living in the United States are peaceful and open-minded. They remain ready to help a neighbor in times of need. As we move through the present challenges in the country and around the world, we can benefit from calling upon the spirit of the immigrant, part of us that is forever open, ever ready, unwavering, willing, courageous, determined, resourceful, humble, ambitious, hardworking, expansive and brave. The call of the time is to connect to our ancestors who helped build this nation so that we, too, can build a better future for ourselves and our communities, one united in trust and respect.

I’m a Descendant of Slaves and Slave Owners

“Statistically insignificant.” That was my sister’s response when I told her that my DNA test revealed that I was three percent West African. I thought she’d be surprised or shocked. I didn’t expect sangfroid. Being a person who’s always been interested in genealogy, I was anxious to research my roots and find out if there was any evidence of this “insignificant” drop of African blood in my family’s history. Before climbing every branch of my family tree, I thought I’d ask family members if they knew anything about any rumors or stories of Black ancestors. That was a mistake.My father died several years ago and his sister is his only surviving family member. Let’s just say she didn’t rejoice at the news of our expanded ethnicity. “There’s no way we had slaves in our family!” my aunt barked.“I didn’t say they were slaves,” I replied too meekly.“Well, they were Black, so what do you expect they were?” she said, obviously finished with the conversation.

That was a mistake.

My Ancestors Saw People as Property

Hanging up, I thought about what she said. I knew that on both sides of my family there were slave owners. I don’t like writing those words, but I don’t like running from it, either. I have a copy of my tenth great-grandfather’s last will and testament wherein he bequeathed a “negress named Diana” to his daughter and her husband. When I found that will and read that clause, I winced. I didn’t want to think that someone known for having fled England for the purpose of freely practicing his concept of Christianity would not only presume to own another child of God, but to hand them down like property to his posterity. But there it was in black and white. I dealt with it by focusing my genealogical endeavors on my numerous indigent ancestors, most of whom were treated by landowners as little more than chattel themselves. That didn’t make them slaves, though, and I was determined to find out if the West African component in my DNA came from enslaved people.It does.

I Discovered the Roots of My Family’s Names