The Doe’s Latest Stories

What It's Like to Work at a Congressional Newspaper

It took six months, but after I graduated from college in May 2007, I managed to find a job in my major—print journalism—in November of that year. I started at a congressional paper at age 23, young by any standards, especially in the cutthroat world of news. Since the paper covered the individuals that worked on Capitol Hill, I started soliciting senators and members of Congress for op-eds on themes like energy and the environment and transportation. I looked forward to writing the neighborhood sections, where I was sent out to explore different neighborhoods in the D.C. area. It was then I truly got to know the city. To this day, I love to check and see if my restaurant review is still hanging up outside the women’s bathroom at a downtown steakhouse.After a few years of being the special sections editor, I was given an extremely unique opportunity. The paper wanted to start a website about the social scene in D.C.—a Page Six of Washington, if you will. I was given an old Kodak point-and-shoot digital camera and a notebook, and my iPhone went with me everywhere to take notes, snap extra photos or record interviews.It was daunting at first, to go to a party being media and not technically being invited. There’s nothing scarier than walking into a fancy party not knowing a soul. My very first opportunity came at a breakfast event for Avon. I was able to interview Reese Witherspoon, as she was the honorary chairwoman of the Avon Foundation for Women. Reese had a cold that morning, but she was just as nice as ever. After that interview, I was hooked. It’s hard to believe it was 12 years ago.

I had plenty of surprises.

I Met Celebrities and Had Unique Experiences While Covering Local Events

I think the most fun I had working at my first job was getting to attend three White House Correspondents’ Dinners. They were held every year at the Washington Hilton in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of D.C. Imagine the biggest ballroom you can think of draped in gold, with the finest linens and stemware. The funny thing is, the food must not have been something to write home about—I can’t remember a thing I ate. Being in my early-to-mid-20s, it was the perfect time to be out late attending parties, as I was not tied down with a child, pet or husband (let alone a boyfriend for that matter). It was during those dinner weekends that I got to meet so many celebrities. My wall in my office at home has photos from those fun memories, including me with Kim Kardashian (she was so nice—her mom was the pushy one), Diane Keaton (an absolute delight) and Jimmy Fallon (as hilarious in person as he is on TV), among others.I got to meet Mindy Kaling, who actually stood and talked to my friends in the media and me. I remember tracking down Paul Rudd the first year because of my love of Clueless. He looks as young as he does in photos. My youngest sister is jealous of the photo I have with the Jonas Brothers, Demi Lovato and Danielle Jonas. I am forever grateful I had such a singular opportunity at such a young age to meet all of these celebrities.Of course, during my five-and-a-half years with the print paper, I had plenty of surprises. One of the biggest ones I like to share is when Jennifer Aniston and Angelina Jolie were in D.C. for separate events. I’ll never forget that during Aniston’s event, she came out for a brief minute and waved to us and then disappeared. I was annoyed that we stood in the press line for about two hours and she didn't really give us the time of day.Jolie, on the other hand, during a premiere of her movie In the Land of Blood and Honey at the Holocaust Memorial Museum, took the time to speak to every single person in the media line. I was impressed with how she took her time to answer at least one question from every one of us. I thought it was very meaningful, especially given the seriousness of her movie, set against the backdrop of the Bosnian War.For all the celebrities I got to meet, I was able to interview lots of people famous in D.C. I interviewed Ben Bradlee, best known for his coverage of the Watergate scandal. I also got to interview various ambassadors, which opened up invitations for me to attend opera balls, which were always hosted at area embassies. I was lucky that my two best friends are men, as I just alternated taking them to various balls and galas, and boy, did we have a blast. As 25-year-olds, we had no business hanging out with older millionaires, but we did. Not only did we get to try food we wouldn't normally get a chance to eat and sample cocktails with liquor that cost more than a few weeks' rent for us but also we learned a lot about how important it is to not take yourself too seriously (because a lot of the people did). We also learned more about our own tastes—what foods, musicals, operas, art and shows we liked.

It turned out to be the best thing for me.

I Love My Current Job, but I’ll Never Forget My First One

Unfortunately, the paper closed their social site due to budget cuts. Toward the end, it got very competitive and cutthroat, and I was tired of trying to work from home before remote work was in. I would get phone calls offering media tickets to certain events and my co-workers would make up stories that I was inviting my boyfriend to things. Meanwhile, I was 100 percent single. I would be constantly in trouble with co-workers for coming in around 10 or 11 a.m. when most nights I was out until 10 or 11 p.m. and stayed up until midnight or 1 a.m. adding the pictures I took and doing a write-up of the event I attended.When I did get let go, I was so upset. It turned out to be the best thing for me. I am now my own boss as a freelancer and have had the opportunity to interview celebs like I did when I was younger, and I get to make my own hours and choose my own assignments.I call it a win-win, although I am very grateful for the experience I did have in my 20s.

Working for a Media Agency Nearly Broke Me

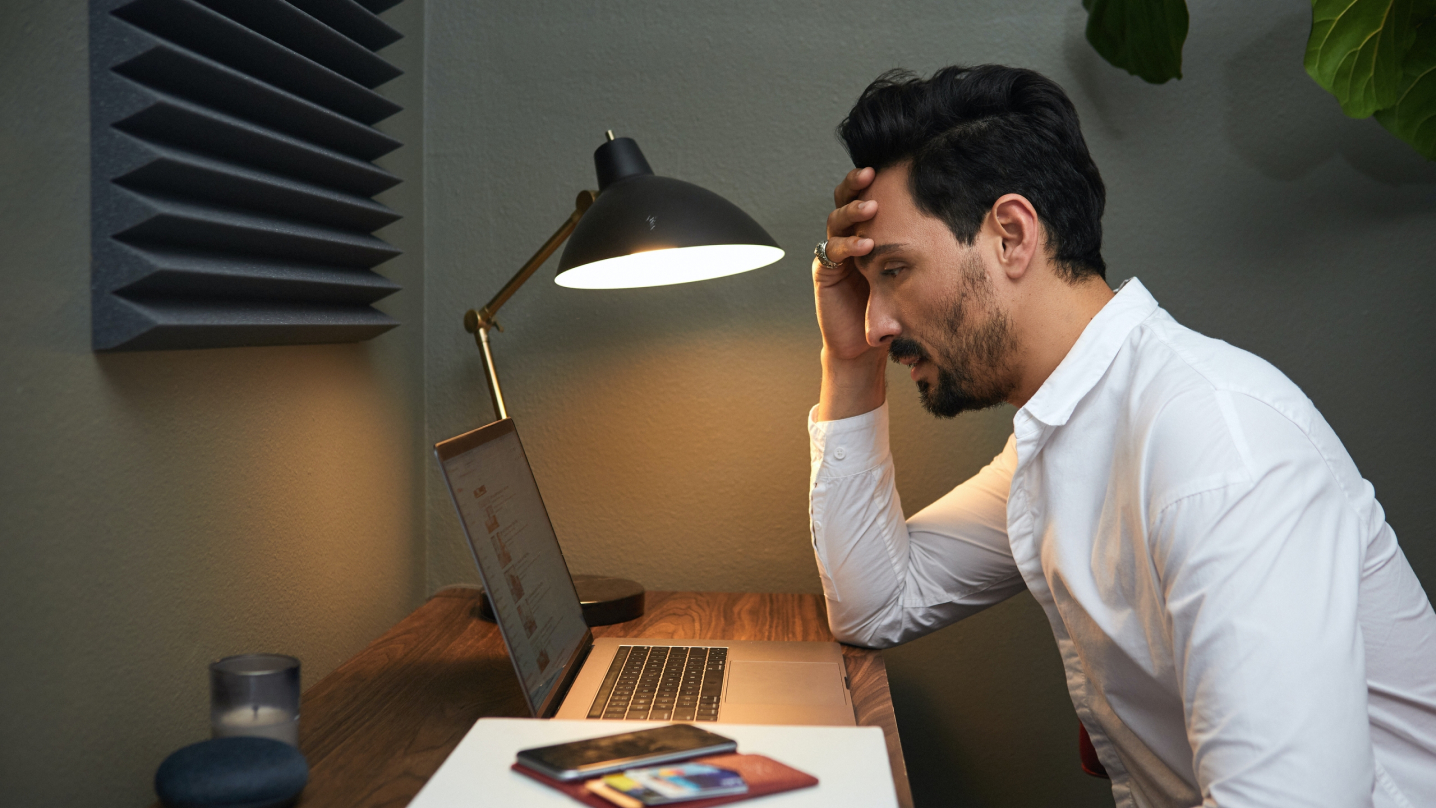

It was my first week as a social media associate at a big New York City agency. I was being trained for the job by another junior-level employee and, at some point, I realized that a large portion of our conversation centered around how to protect myself. This should have been a red flag, but I was naive. Advice that seemed innocuous enough—put everything in writing, explain your rationale and always have at least one senior team member sign off, in writing, on what you're doing before you do it—just seemed like good business practice. In fact, they were going to become defenses I’d have to employ daily to avoid the finger-pointing, blaming and lack of ownership from the agency’s senior leaders. I would say thank goodness I always had the receipts, but sometimes even that didn't save me. Excited to be working my first “real” job and eager to be a good soldier, I adopted the practices I saw around me: Show up early, stay late and if a client asks for something, the answer is always yes. I’d come in at 6 a.m., posting and emailing on my commute, and kept working after I got home at night. Through spoken and unspoken norms, the message was clear: The agency would always come first.

The agency would always come first.

Work Always Came First—No Matter What

About a year into the job, I broke my wrist. On a Sunday night, as I took the subway home from urgent care, my wrist wrapped, padded and slung for protection, I shot a quick email over to my manager. “Hi,” it said. “Unfortunately, I broke my wrist this evening, so I will not be on tomorrow morning and will miss our call. Thanks for understanding.” The response came quickly, despite the lateness of the hour or the Sunday-ness of the day: “So sorry to hear that! No worries about the call, just message me once you’re on.” If that message wasn’t clear enough on its own, the email I received the following morning—with the headline, “IMPORTANT When You Sign On - DUE,” followed by that day’s date—cleared up any ambiguity. I was expected to work, in one piece or not. In total, I took off a whole two hours for my broken wrist, returning straight to work after my doctor put a cast on. That I might benefit from taking the day off to rest and recover was never considered.At the agency, “working hours” seemed a laughably obsolete concept. Every hour was a working hour if you were dedicated—or scared—enough. It took me a mere matter of weeks to realize that behind every 8 a.m. corporate tweet was a 23-year-old who’d been online for four hours trying to make sure that the link works properly. Often, that 23-year-old was me. The least senior employees were expected to be available at any hour, for any problem, no matter how trivial. But where credit was concerned, there was a clear understanding that any accolades would go to a senior team member, while in the event of any failure, the least senior member would be blamed.At every level, gaslighting was common. Claims of unfair, rude, abusive or unprofessional speech—both verbal and via email—were met with snark and denial. If employees offered even a minor complaint or piece of not-entirely-positive feedback, we’d be asked what we did wrong, how we could have fixed the situation for ourselves. When I finally built up the courage to express that I was feeling burnt out from working 70-hour weeks, I was asked what was wrong with my time-management skills. No one thought to ask my manager why I was staffed at 160 percent.

I Finally Reached My Limit

As my time at the agency progressed, I found myself living in a state of constant anxiety. The preexisting culture was significantly exacerbated by COVID, and the need to be "on" 24/7 only increased. Co-workers would multitask on calls (a practice which was the expectation, not the exception) to commiserate that they, too, had not taken even a short break in hours to use the bathroom or get food. "If this client doesn't stop talking soon," they'd say, "I'm going to pee myself," smiling with dead eyes on the video call all the while. There were days when I did not move from my computer screen for 12 hours at a time. One pandemic afternoon, I took a sip of coffee while on a video call with a co-worker, and she gasped. I looked around startled, wondering what in my absentminded actions could possibly have elicited such a response. “Where did you get that?” she asked, pointing at my coffee cup. “When did you have time to go out?” Realization struck hard—she had noticed the Starbucks logo. “I didn’t,” I said, the urge to laugh warring with the very real resentment this comment engendered. I was quarantined at my parents’, and my mom had been to Starbucks the night before and brought it back for me. In truth, I couldn’t remember the last time I had left the house during daylight hours, let alone for the luxury of obtaining my own coffee. My co-worker smiled knowingly. The final straw came on a Wednesday night in the winter of 2020. I had sat down to work before the sun was up and was still there long after it had set. I hadn’t moved all day. Every time I’d tried to stand up and take a break, a call had come through with something that was “timely” and “just couldn’t wait.” My sister had brought me a snack around midday. Despite my protestations, my family had decided to wait for me to eat dinner. “How late could it be?” my dad asked. At 8:30 p.m., I descended the stairs, exhausted, wrung out, eyes ringing with 14-plus hours of staring at a screen. I let out a sigh of relief as I pulled my chair out to sit. As I moved to take my seat, however, my phone began to ring, the incessant tone letting me know it was business rather than pleasure. “Hi, are you free?” the voice at the other end inquired. “Actually, I was just sitting down to dinner,” I replied, making every attempt to keep the cascade of sass I could feel building out of my tone. “Good,” the voice replied. “Then you’re not busy.” Without missing a beat, the voice began a deluge of “urgent” work that had been relegated to the evening because she had been on too many calls during the day. Tears welling, I stood up, shrugged a deflated apology to my family and returned to my desk. I remained there until after 10 p.m. My food had long gone cold by the time I was done.

My food had long gone cold by the time I was done.

I Quit My Job to Save Myself

I left the agency the following February, essentially as soon as I could get a new job. If I’d needed my decision validated, hearing a co-worker reprimanded for attending a family member's funeral without "advance notice" during my final week was more than enough.Shortly after I left, there was a mass exodus. The environment of agency-before-all-else had finally borne its rightful fruit. There were multiple mental and physical breakdowns and uproar among employees. I’m told it changed nothing.It’s been nearly a year, but my time at the agency has stayed with me. I still wake up in the middle of the night expecting an accusatory email alerting me to some sort of pseudo-emergency that demands my immediate attention. I check everything I send at least three times before it goes out and am sure to have a paper trail to back up why I’ve taken even the most minor actions. A former co-worker, who has since left the agency as well, recently told me they still bring their laptop home at night, even though they’re the only one at their new job who does. “I can’t relax unless it’s there,” they told me. “I’m still afraid of that late-night call or angry email. I always think it’s coming.”

We Need More Data Journalism to Reveal Biased Journalism

Like many cultural reporters I know, I got into journalism for selfish reasons: I like to write. There’s a fair share of us, I must assume, who were actually drawn to reporting because they are genuinely fascinated by the art of collecting information and delivering it to the masses. But many of us are here because we like the sound of our own words read aloud.I didn’t realize the fault in this approach to journalism until my first real newsroom internship, when my editor pushed me to write and publish a story that had style—not content—that made me squirm with unease. The story, a delicate subject with a main source that had brushed with death, was ripe for stylistic exploitation and my editor encouraged me to juice it for all it was worth. The result? An overly subjective, dramatized recounting of events that, while factual and approved by my source, felt to me to be a gross injustice to the story at hand. Since this story, I’ve never looked at narrative journalism, once my dream medium, in the same way.The fact of the matter is, while narrative storytelling touches readers and can stay with them for years (I think of this article often, even five years after first reading it), it is a tool that should only be deployed when appropriate, yet is often abused by view-hounding editors like mine and literary-minded writers like myself. When inappropriately applied, narrative reporting can warp a story beyond recognition, obscuring necessary facts and magnifying others until the final product transforms into literature with little journalistic purpose.In the worst cases, the hidden voice of the narrative journalist can steer readers to a predetermined conclusion. The reporting surrounding the “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?” controversy comes to mind; readers felt manipulated by reporters, specifically because they could barely parse the story facts from the writer’s opinions. While reporting can never be unbiased, no matter the medium, I believe readers deserve news that gives them the chance to form their own opinions—or at the very least, identify the journalist’s personal logic and disagree.This, I believe, is why readers desperately need data journalism.

Many of us are here because we like the sound of our own words read aloud.

What Is Data Journalism and Data Visualization?

Although data journalism technically describes any form of reporting that uses data as a key source, its definition has changed dramatically over the years and varies depending on who you ask. The data journalism to which I’m referring is more accurately called “data visualization” and takes the form of interactive graphics that allow readers to easily explore and manipulate a data set. You likely became familiar with data visualization during COVID while perusing the interactive maps depicting infection rates around the world.I personally became acquainted with data visualization when, a year or so before the pandemic, I stumbled upon The Pudding, a cultural publication whose data essays changed the way I view the format. As you might have noticed, the two articles I have criticized in this essay—my click-fueled drama narrative and “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?”—don’t seem to lend themselves to data visualization, mostly because they are human interest stories. That’s how I used to view data visualization: as an inventive but narrowly applicable tool. If you peruse The Pudding’s stories, however, you might be surprised at how apparently effortlessly these journalists apply data visualization to human interest stories—from colorism in high fashion to women’s minuscule pockets.It was this discovery, of the infinite applications of data visualization in any given sector of reporting, that ultimately convinced me to go back to school for a master’s degree in data science. Pursuing a career in data visualization was a no-brainer for me, not only because I’m a visual learner but because I struggle with the knowledge that my inherent biases will always impact my work and, by extension, my readers.

This, I believe, is why readers desperately need data journalism.

How Data Journalism Can Kill the (Silent) Author

Click through a map of COVID infections and you’ll start to get an idea of how data visualization can allow readers to hold more power over their own learning by doing away with what I like to call the Silent Author. The Silent Author is the quiet bias journalists bring to their reporting, the assumptions, personal opinions and blind spots we (intentionally or not) sprinkle throughout our articles and which often go unnoticed by the author as well as the reader.Say a reader is investigating infection rates around the world to plan a trip. A data-driven article outlining the safest countries to visit during COVID might be informed by the journalist’s interpretation of infection data, but it is limited to just that: their personal interpretation, which likely includes unconscious biases, like which countries are worth visiting in the first place. For a multitude of reasons, these biases can go unnoticed by the reader; for example, it is difficult to perceive when the scope of an article is warped or when an author makes an interpretive leap that they wouldn’t agree with. Many readers simply don’t think to question a journalist’s authority, especially when they publish with a major news outlet.In contrast, an interactive map of the same data set allows readers to peruse infection data free of the Silent Author’s guiding voice. Of course, data journalists usually accompany interactive graphics with their own analysis, but their biases are no longer silent; readers can approach the author’s interpretations with a critical eye by exploring the data themselves. Data visualization takes your middle school English teacher’s instruction to “show, not tell” seriously, with the added bonus of allowing you to do both and giving the reader the opportunity to determine whether your “show” and “tell” match up.

We Can Never Get Rid of the Author Entirely

You’ll notice that even this essay is biased. Unfortunately for you, I have only just started my data science degree and am not yet capable of producing a graphic that allows you to compare the bias in traditional print journalism and data visualization. Instead, I find myself, a self-professed data visualization zealot, writing an article that focuses on the positive potential of this reporting style. But, in an attempt to be a Not-So-Silent Author, I will tell you that data visualization is not, and could never be, truly unbiased.One of the greatest flaws in data visualization projects is that we often mistakenly consider data objective when in reality, data sets are inherently skewed. Take our interactive COVID infection maps, for example. Not all countries are equally efficient or honest ind their reports of infections, China being a noted one. This alone will warp a graphic’s accuracy. In other cases, journalists might use data sets that are not large or diverse enough to be representative of the population or subject at hand. Worse yet, since journalists rarely collect their own data sets, there is always the possibility that a reporter might knowingly or unknowingly use one that has been produced by a disreputable source. And then, of course, data visualization does not solve the issue of story choice bias, wherein the stories that make it to publication always reflect an editor’s opinion of what (or who) is important enough to merit news coverage.All of these factors and more prevent data visualization from being some sort of perfect solution to media bias, but such a solution will never exist. Data journalism as a whole has long been heralded as the solution to any number of media woes: gendered harassment in the workplace, bias in reporting, the existential threat of how to provide reporting of increasingly higher quality, among others. While I don’t believe data visualization will solve any of these puzzles, the way I see it, it is the next step that journalism can take toward owning up to the natural biases that reporters bring to their stories.

We Need to Get Rid of Journalistic Objectivity

In a year that broke the record for fatal anti-transgender violence, I knew it was my responsibility as a queer journalist to write stories in a new way. I wanted to cover transgender people working to end this violence and collaborate with them to craft stories. News needed coverage of gender-diverse people the community had not been granted before—movement journalism that pushed for change. While working as a news reporter at a traditional, long-standing publication, I strived to push against narratives that criminalize gender-diverse people. Although I’m paid to write news, I broke the arbitrary yet sacred rules of objectivity that have become ingrained in my profession. I penned an opinion article addressing the way media outlets frame gender-diverse people. I publicly came out about my gender queerness and the challenge of coming to terms with my identity while rhetoric blasted across my screens. Last year, a transgender person in Los Angeles was accused of being a predator while changing in a dressing room that aligned with her gender identity. Media outlets misgendered her and dismissed her identity. Right-wing pundits rambled on about the incident for days, using it to emphasize their anti-transgender takes. I decided a story needed to be told without prioritizing the idea of balance that journalism schools tell us news requires.I was the only person who could tell the story with such an impact at my publication. But I needed to bend the rules to do it justice.Writing that story took me months. It required me to scroll through Reddit threads where anonymous posters called people like me perverts and weaved together a made-up moral panic. It stoked my depression, dug my flailing mental health into a deeper pit. But there wasn't any support from my company—only constant reminders about the kinds of tweets we should avoid sharing in order to seem like we’re not taking sides on any issue. Meanwhile, leaders at my publication spent weeks debating if we should use gender-neutral pronouns in our content or write around them.

Although I’m paid to write news, I broke the arbitrary yet sacred rules of objectivity that have become ingrained in my profession.

For Me, Objectivity Is a Workplace Hazard

My therapist tells me I should take a break and write lighter stories. She’s told me I should figure out an escape plan from my current job, define what it will take to know enough is enough. But I worry that if I leave, no one will write about these pressing matters, the people and pillars holding up fragile populations.I haven’t quite figured out what’s going to be the straw that breaks this journalist's back. But I know bearing the responsibility of covering long-suffering populations is not sustainable. I know I won’t be able to push for justice and foster change by continuing to pretend like I don’t have an opinion, proceeding to abide by these antiquated rules that no longer fit what’s needed of journalism. Constantly having to validate facts I and others know from being immersed in these communities to be true by trying to obtain false balance will one day stifle me so much I’ll feel crushed.I can’t fully report on people who need more of their stories told with the myth of objectivity constraining me. Practicing objectivity erases what I set out to do as a journalist: to humanize issues, amplify voices and support people whom society has sidelined far too long. Journalists need to be humans first; we need to listen to the people we’re writing for. Questioning people’s needs or concerns to death takes the heart out of our work.

Who Are We Staying Neutral For?

Journalism schools drill into reporters’ brains that we must remain neutral, appear as blank slates without any obvious opinions. Media leaders need to accept that news has never been apolitical at its core. I’m working from within my mainstream publication to break these molds and be both an advocate and a journalist.I told my editors I want to focus on writing queer stories at the perfect time (for them). Shortly after the murder of George Floyd and the racial justice reckoning that followed, my publication decided to form a team of journalists dedicated to covering groups it had long overlooked. It’s a vague, nebulous beat, writing about “cultures of marginalized communities,” which is generally understood in my team as anyone who’s not white, straight, cisgender, financially stable or neurotypical. The publication assigned me and only four other journalists the responsibility of building relationships and expanding coverage of communities it neglected across several states. As the token queer person, I’ve strived to make up for lost time and form connections with LGBTQ+ people in my area. Like most people, LGBTQ+ folks are grappling with challenging years, from the high rates of anti-transgender violence to harmful legislation. Carrying the burden of being the sole person covering these stories weighs me down on its own, and my duty is balanced on top of the boulder that journalistic objectivity places on my back. More than a year has passed since my publication, like many others, vowed to transform both the makeup of our staff as well as the people featured in our stories. But we’re still not writing for sidelined communities—we’re writing about sidelined communities for the same readers as before. Our staffs are still overwhelmingly white, and pay equity has been reduced to a buzzword leaders use in speeches aimed at preventing employees from unionizing. We’re still creating content that’s palatable for certain audiences. Our work is boiled down until it appeases our white, older, middle-class subscribers. (Many of my stories, including those with information that could help low-income people, are trapped behind paywalls, but that’s another story.)Instead of connecting communities to information they could use and publishing stories that people can see themselves reflected in, the stories I write seem to be teaching the ignorant, both in my company and out. I’m asked in every article to spoon-feed information, like describing what they/them pronouns mean.

Our work is boiled down until it appeases our white, older, middle-class subscribers.

I Want My Work to Make a Difference

I set out to do this job to make a difference, and by no means do I think that makes me unique as a journalist. To do that, I want to highlight and reach audiences that mainstream media has not. I try to write pieces about triumphs and solutions LGBTQ+ folks found for themselves without the help of corporations, police or the medical-industrial complex, as well as other entities journalists have relied on as sources.We need to educate journalists, not just small teams like mine thrown together to give publications the appearance that they equally cover everyone. And by “we,” I don’t mean people who live through being a sidelined community every day. On top of my reporting work, I’ve been tasked to teach my colleagues about LGBTQ+ topics, work for which I am not paid. At the very least, pay your employees for their extra labor to fix your ignorance. Journalists should read content from people inside marginalized communities and understand their own privileges. They should read books like Lewis Raven Wallace’s The View From Somewhere, which breaks down the myth of journalistic objectivity and explains a new way of reporting that’s necessary for the stories that need to be told now. It’s time for the long-standing ideals that attempt to erase our humanity, our thoughts and our lived experiences to disappear.There’s room for journalists to also be activists and to support the communities we cover instead of merely reporting on them. People trust those that they know, whose beliefs they can see. It’s time for a change. Luckily, I’m quite young. Soon, the walls that journalism’s elite built up won’t stand any longer because of reporters like me.

Live Audio Offers Media the Emotional Maturity It Desperately Needs

I was invited into Clubhouse relatively early in the pandemic. It was August, a few months after the app launched and everyone was stuck in quarantine. The friend who invited me to join said I would love it; it would be the perfect place for me to engage in conversations and connect with new people and old friends. She had been participating in a political club on the platform that was focused on sparking youth engagement in the November 2020 elections.Upon entering Clubhouse, I was blown away by all the conversations happening amongst friends whom I’d known for years. It felt like an intimate place, where we could gather around our phones and chat about anything until the wee hours of the night. There was something unique about hearing other voices, their emotions and honesty, that made the app feel special, unlike any other social media I had ever experienced. It was like we were all gathered around a fire pit or hanging in someone’s living room.

I couldn’t believe I was actually making real friends with brilliant, creative, complex individuals through this digital social media platform.

I Was Able to Connect With Others on Clubhouse in a Unique Way

As more and more folks joined the app, there were waves of new voices and topics of discussion. Throughout those early days, I found the majority of conversations to be focused on big techie topics like investing, pitching your business, diversity and inclusion, media, arts and culture, health and spirituality. Though I had some interest in these topics, I knew there was a deeper layer where we could go to truly discover who we were. Instead of vying for the smartest sentence, we could share our honest stories and less of our opinions. As someone living with chronic disease and focused on studying love in practice, I knew in sharing my story, I could host that space for more depth that I knew was available. I started my own club and began hosting vulnerable, honest conversations about love, facing disease, mortality and creative expression. As the conversations transpired, I’d learn others’ stories and build relationships. My new Clubhouse friends became real friends, and we’d chat on the phone or via Zoom occasionally as well as co-host rooms together. I couldn’t believe I was actually making real friends with brilliant, creative, complex individuals through this digital social media platform. I had never found this level of connection on any other social media apps that espouse likes, loves, short-form comments and limited characters. Often when hosting an especially honest room about love and life, I would ask everyone to take a moment to pause and just feel the connectivity in the space. We were in the digital world, sometimes sharing our most intimate secrets with complete strangers who were tuning in from thousands of miles away, and we could all hold it together. We could all respect each other and lift one another up. The energy was palpable and powerful. It was also healing in a time of great international distress.Since those early days, my club has grown to surpass 75,000 members, and we've had hundreds of amazing salons on topics ranging from health and well-being to creativity, abolition and love (and it’s still very intimate based on the titles of the salons and the limited folks on stage at a time). This last year and a half on Clubhouse has shown me the power live audio offers in bringing disparate voices together and building bridges across our differences. I believe this is the path to a new value set in media where honest, emotional depth and lived experiences hold currency alongside intellectual debate.

I know this type of media is just beginning, and there is an immense opportunity to use it as a salve for our wounded communities.

Live Audio Could Be a New Type of Comments Section

I’ve discovered how live audio can transform media from one-sided reporting, opinion sharing or cross-talking battlegrounds to (when well facilitated) dynamic, inclusive spaces for debate, curiosity, expression, honesty and connection. I see the opportunity for live audio to become the basis for a new kind of comments section, a space where profane insults and trolling aren’t welcome but rather healthy, generative conversations can take place around any topic with a baseline of mutual respect baked into the agreements for the virtual shared space. The beauty of this opportunity is that it can also be recorded, with a new type of open conversation podcast format. The audio published would have the capacity to represent public debate and discussion on any issue, and audiences could be defined through various identifiers to better understand who’s in the room so hosts understand what bridges they may be building (or not) across diverse groups. Though my specialty may be focusing on personal narratives, well-being and exploring challenging life experiences, others could dive into politics, history, sports, art, culture, religion or anything else that brings people together to connect beyond just facts and opinions. The key to this framework, acting as a tool to heal our broken media landscape, is trained moderators and facilitators who infuse curiosity and strong moderation skills with excellent and well-defined boundaries and frameworks for discussion. From what I’ve experienced on Clubhouse and the myriad of live audio platforms—like Greenroom and Twitter Spaces—springing up, I know this type of media is just beginning, and there is an immense opportunity to use it as a salve for our wounded communities and our challenges with communication across difference. Jump in and let’s jam in the virtual living room.

Detective Therapy: How Podcasting About an Unknown Comedian Changed My Life

In 2011, at the start of a boom, I started my own podcast. Plenty of people had already established themselves in this space, and many popular shows with celebrity hosts wouldn’t begin until much later. Eleven years ago, however, you didn’t need a theme for your podcast to set it apart—you just needed to be funny. I’d been doing comedy for years, recording just about everything I did, but I assumed that the world didn’t want to hear undeveloped comedy (I’ve since been proven wrong 10,000-fold). Still, I didn’t have to think for long to decide what my show would be about. Not only did my two best friends, Dan and Mike, grow up doing comedy as a group with me, but we listened to comedy records together, mostly on cassette tapes and many on vinyl. I decided that’s where I’d start (and likely end) my podcasting career: vinyl records.I spent the first year or so becoming an increasingly voracious comedy album collector, building up the guts to speak with some of my heroes. I could end this here and tell you that I recently interviewed my white whale, the comedian at least partially responsible for my friendship with Dan, as the show’s final episode. The thing is, though this episode was massive for me, it didn’t change my life or why I podcast. It would take a genuine mystery to do that.

My Friend Went Missing and I Started Sleuthing

This mystery had many stops and starts. I first interviewed a comedy historian about a stand-up whose true story was almost entirely unknown. He was a white guy from Arkansas who did race-positive humor in the ’60s, and that was about all anyone knew about him. I soon became obsessed with finding out why he had disappeared, but within a couple of weeks of research during my day job, I threw up my hands. I didn’t know where to start. Over the next three years, I’d publish my second book, sell my first movie and make hundreds more podcasts. The latter was an absolute compulsion, the easiest and quickest way I’d felt like I’d created something. I was churning out discussions and rarely editing (I didn’t need to since my guest would discuss liking a specific record). Then, in early 2018, amidst the normal blur of back-and-forth emails with comedians’ agents, I got a message that had nothing to do with comedy records.Mike had just been reported as missing. In fact, he’d been missing a few months after I’d first heard of this unknown comic. I spent the next few weeks in a fugue, searching not as someone with the fervent, distracted interest of a guy who didn’t care about his day job but with the passion of someone who didn’t want to believe the worst. I hunted down every lead I could online, doing the best near-forensic work I was capable of. I analyzed photos of this and that and checked out social media that might hold clues, desperately hoping to get in touch with Mike, to find out where he’d gone to and why he’d cut off contact with everyone.I didn’t entirely process my guilt over our mutual lack of correspondence; instead, I turned it into dread. Mike was the reason I’d become a director. He taught me the joy of telling childish jokes well past childhood. He reminded me to find the absurd in everything; I think he would appreciate knowing that I accidentally walked a few miles out of my way to go grieve at a bowling alley the following week.

My friend was no longer missing. He’d been found, just not at all in the way we’d hoped.

I Began Interviewing Family Members of Deceased Comedians

A few months later, we got the news that Mike’s remains had been found buried on his own property. I collapsed in on myself, unable to do much for my own good or those around me. There was no more searching to do to try and keep my soul afloat. My friend was no longer missing. He’d been found, just not at all in the way we’d hoped. It was no longer a mystery.Shortly after, I started a miniseries on the podcast interviewing the family members of album creators who were no longer with us. This was my effort to start using the show to tell the stories behind these records. These were mini-mysteries that could be solved in the room. In the quest to make busy work for a trauma-addled brain, I was satisfying the need for something good to come from loss. No one else was going to tell these stories if I hadn’t called them up to talk.Still, these were not much different than other podcasts. They were fun discussions about people who were almost lost to time. I wasn’t processing my need for them yet. Toward the end of the year, though, something suddenly clicked. I thought back to my hayseed in a needle stack, wondering if my skills in finding these other obscure names might help me find this country comedian.The worst that could happen was finding zero leads on this comic. The best I could hope for was that he’d be alive, want to speak with me and tell me his whole life story. He became an even stronger obsession than the search for my lost friend; there was no way I could be in denial about whatever was at the end of this tunnel. As for podcasts, this time the journey would have to be the episode, regardless of the outcome.

A Phone Call Changed My Podcast Career

I recorded what I did every step of the way, including my phone calls, and read newspaper clippings out loud. I kept writing physical letters to people who shared the comic’s stage name. I abused free trials to research websites (which only help you when the information you have is accurate to begin with) and kept coming up empty. I’d even found some information that told me this Arkansas comic was actually the son of a rabbi from New York City. But even then, no one knew his real name. One website said (in small print that I almost missed) that one potential name “may go by” the very stage name I had been searching for. It was too simple to be true, but I dug further. I found a brother, but I had to write another physical letter and wait for one back. It never came.Fortunately, though, I did get a phone call. The comic had passed away, but his family remembered him fondly. When I said earlier that the journey would have to be the story, I meant it. Even if the journey had sucked, I still would have published it. This phone call led me to finalize a script, something I’d never needed to write for a podcast.I included many interviews in this episode, but it primarily contained narration and royalty-free music to serve the story. I took years of album and film editing and used them to express my love for comedy and my passion for untold stories at the same time.

They brought tears to my eyes.

The Mystery Comic Now Plays a Crucial Role in My Work

It wasn’t obvious then, but Mike was part of the reason I had even learned to edit. Now he’d become the reason I had to edit, even if the story wasn’t his. The comic’s family loved it, especially his niece, who shares a name with Mike’s mom. She recently found two unreleased records of his, from his early days, which an archivist friend of mine digitized and cleaned up. They brought tears to my eyes. Not from laughter—funny as they were—but from knowing his story hadn’t ended.Archiving the lives and works of unknown comics is now my passion, even though I’ve ended the show. I’ve started searching for other comics to research, all in the name of preserving laughter, art and toil. As I write this, I’m helping to put together the Arkansas comic’s first vinyl release in over 50 years, working as his estate archivist and researching a book on his life, despite never having met the man. All this effort has made me realize I have more stories in me and more to find. I continue to search for the next comedy mystery to explore, in honor of the comic, my late friend and my own sanity.

Freelancing Sucks: My Professional Writer’s Group Is Really Just Toxic, Neoliberal Self-Help

There’s apparently an app for freelance writers that allows you to turn yourself into your own nightmare Taylorite panopticon, monitoring the prisoner/employer who is yourself. You’re supposed to log in at 15-minute increments, reporting to the manager (who is you) about whether the employee (also you) is optimally performing to maximize profits or is slacking off by getting a snack or messing around on social media or pausing to contemplate the yawning abyss of guilt and self-loathing that has opened in their soul for some reason. I found out about this app through a post on a professional network for writers. I will call this professional network “George.” George is a supportive online community where writers share past successes, talk about strategies for future successes, problem-solve barriers to success and explain how you, too, can get a byline in leading venues like The New York Times and also The New York Times.I sound helplessly bitter because I am a bad person and also bitter. I have never been published in either The New York Times or The New York Times. But, even so, George is a great community in many ways. There are helpful posts about job opportunities. People offer advice about how to pitch to this venue or that venue. The comments are moderated within an inch of their lives; it’s one of those rare internet places where you almost never see people being horrible to each other. Everyone is polite and upbeat and focused on success.That’s the good part of George. The less good part of George is that everyone is polite and upbeat and focused on success. It’s community as neoliberal self-help regime.

When people advise you not to write for less than $1 a word, and you are lucky to get a tenth of that in many cases, it doesn’t exactly feel supportive and inspiring to hear about the fortunes of your betters.

The Neoliberal Mindset Has Encouraged Self-Exploitation

“Neoliberal” is a word that gets thrown around with a certain cavalier disregard for context. Originally, neoliberalism referred to the Reagan/Thatcher deregulatory program of the 1980s. Conservatives of that time argued that everyone was better off without government oversight—that if you freed people from the chains of taxation and welfare payments, they’d pull themselves up by their toenails even if they didn’t have shoelaces. Old-school capitalism praised the capitalists. Neoliberalism still praises capitalists, but it also touts the potential capitalist in all of us. You (and you!) can be your own overseer, fashioning yourself into your own lucrative brand as a gig worker entrepreneur, vigorously exploiting yourself for the greater glory of yourself. George is the friendly hum of the neoliberal treadmill scrolling by in encouraging post after encouraging post. The community perceives itself as a collection of canny managers, all sharing strategies for getting the most out of their workforces of one. Network! Connect with editors! Don’t sell yourself short! Negotiate those rates up and up! Share your triumphs so people can see how awesome you are, improving your brand and setting yourself up for more triumphs to come.

Freelance Writers Do Not Control Their Own Fate

The relentless tread of triumph is, obviously, a little disheartening if you are not notably triumphing yourself and haven’t increased your modest yearly income in over a decade. When people advise you not to write for less than $1 a word, and you are lucky to get a tenth of that in many cases, it doesn’t exactly feel supportive and inspiring to hear about the fortunes of your betters. It feels like you are a losing loser who has lost the game of George.This isn’t about jealousy and sour grapes. Or, OK, it is about jealousy and sour grapes. But writing is often an exercise in jealousy and sour grapes. And that’s not because writing is an especially difficult, courageous, spiritual whatsit. It’s because writers are not, in fact, for the most part, hard-charging capitalist managers maximizing our abyss-gazing time via apps. We’re workers. And being workers mostly sucks.If you read George posts, you get the impression that freelancers control their own fate—that if you just get the right information, you can write the right pitch and take the next step in your career. But the truth is that most of us don’t actually have careers. We’ve got cobbled together gigs that lead nowhere in particular, except to the certainty of sporadic failure and humiliation. Freelancers—like most workers—have virtually no power and no leverage. I’m rarely in a position to negotiate terms or ask for more money. The industry standard is that you do the work, and then they decide if they’re going to pay you. Sometimes, an editor will reject a piece for no reason and refuse to give you anything for it. Sometimes, an editor will be rude and abusive for no reason. Editors can yell at you for disagreeing with them on social media. They can end a decade-long relationship with no explanation. They can just disappear and stop returning your emails. There’s nothing you can do about any of that, for the most part, except grin and bear it. Or not grin and sink into despair, as the case may be.

Being workers mostly sucks.

A Community of Empowerment Rarely Highlights Its Inequities

George isn’t completely oblivious to these dynamics. Every so often, you catch a glimpse of collective misery lurking there beneath the carefully preserved veneer of collective cheer. There are posts about trying to pry money out of editors and about editors arbitrarily killing pieces. There are posts about how the industry is dying. There are occasional despairing posts about how you, in fact, cannot get $1 a word anymore. But these are framed as obstacles to skip over on the road upward, rather than as regularly encountered walls in the dead-end maze. A community devoted to career empowerment isn’t going to dwell on collective powerlessness. If you’re lying in bed, contemplating the low ceiling and nonpayment of another invoice, maybe just get that app and pretend you’re a manager whipping yourself into a flurry of activity, controlling your own destiny by quantifying and regulating your own bathroom breaks.Even berating George is mostly an exercise in self-chastisement. How can I be better than George, after all, when I am in George? In the unlikely event that I ever get a byline in The New York Times or The New York Times, I will tell my mom, and then I will share it with George. When people say they are getting paid umpty umpty umpt and no less, I do not say, “Well, I’m grinding out listicles for a content mill at eight cents a word,” because who wants to tell your colleagues, “Hey, I’m a failure.” I pay attention to my brand and manage my time. My inner George gives me a thumbs up. I try not to gag on it.

I’m Catholic and I’m Vaccinated

As I scroll through the once-friendly space that is social media, I can't help but feel dread as I see yet another friend or family member fall to misinformation and selfishness. It makes me sad and angry that my relatives and acquaintances have put blind zeal above science and healthcare and become anti-vaxxers. I'm a devout Catholic, and I can barely recognize my church anymore.The church has long taught that caring for the sick is a priority and a noble deed. There is a list of “corporal works of mercy” that are like guidelines for good works. One of these works of mercy is to visit the sick, but it is extended to caring for and loving the sick and being present with them. The corporal works are meant to be calls to action, not a sedentary response. This is the place where many Christians fall short, including myself. We shout our beliefs but don’t help those who need it the most. We cry for justice and mercy but offer none. We impose morality yet do not live it.

I'm a devout Catholic, and I can barely recognize my church anymore.

Religious Exemptions Don’t Hold Water

Recent events among Christians have shown no regard for the elderly, the immunocompromised and the chronically ill. The people I once knew as generous and selfless are in fact despicably narcissistic. They cling to a religious exemption from the vaccine and hypocritically declare their selfishness to anyone in earshot. But while I am depressed to see their ignorance damage society, the church and themselves, I understand where they are coming from.I have friends and family who have claimed religious exemptions from the vaccine mandate on the grounds that the vaccines were derived from aborted fetal tissue. Those who believe an abortion is a death have said that they cannot take a vaccine that was derived from such means. From the religious point of view, forcing a vaccine mandate is forcing someone to take a vaccine they believe came from a death, which is highly immoral.I understand this logic because I am pro-life, but I still got vaccinated. For me, it was an easy decision. I’m an environmental engineer but also spend a great deal of my free time reading moral theology and philosophy. While many perceive this as a dichotomy, I believe in the cooperation of science and theology. They are not meant to battle, or even simply coexist, but to build each other up and help us understand God and our life on Earth. I believe that even though the vaccine was the result of a death, we should not let that loss of life go to waste. I believe good can come from bad.The vaccine has and will continue to save lives. Why reject something that has already been done? The church has an obligation to protect the sick, which is why even Pope Francis has requested all the faithful to take the vaccine.

Christian Anti-Vaxxers Are Hypocrites

We can see the irony in the defense that some use to seek a religious exemption. They steal an argument out of the pro-choice book and claim "my body, my choice." They believe their appropriation to be a strengthening juxtaposition, but in reality, it buries their argument in a shallow grave of ignorance. Catholics claim that abortion is not adequate healthcare, which leads many with opposite beliefs to think Catholics do not understand proper healthcare. The church’s response to the pandemic has only deepened those doubts. For a group so deeply enmeshed in the healthcare system, it is surprising that we would not jump to the safest and most reliable defense against a deadly disease. The Catholic Health Association of the United States runs over 600 hospitals and is the largest group of nonprofit healthcare providers in the country. To me, the most worrisome issue regarding this pandemic is that the Catholic Church will damage its reputation for healthcare, its pursuit of moral science and its support for those in need.When I have the opportunity to speak on this matter, I generally choose my words carefully. My purpose in discussing this topic is to start a conversation about selflessness. As Christians, we believe the greatest sacrifice one can make is for their neighbor. It’s the golden rule that is so ingrained in our culture: Love your neighbor as yourself.

We cry for justice and mercy but offer none. We impose morality yet do not live it.

The Unvaccinated Aren’t Beyond Redemption

I believe that those who choose to be unvaccinated based on religious grounds are selfish. On the other hand, I also believe it's selfish to dismiss these individuals as too far gone for redemption. Having discussions with your friends and loved ones about the importance of the vaccine is the only thing that will push them to get it.I have a friend who’s a nurse in a pediatric ICU. She has seen hundreds of children suffering from COVID over the last year and a half. Up until a month ago, she was unvaccinated for religious reasons because the vaccine originated from aborted fetal tissue. She decided to get vaccinated because she served so many children on the verge of death that she couldn't bear causing that pain to a child. Her husband is still unvaccinated. Their children are unvaccinated. My family continues to push for them all to become vaccinated.The vaccine should not be a personal choice—it should be a mandate, regardless of its origin. It will save more lives than its cost. I ask those reading to continue to have conversations with their loved ones about getting vaccinated. It may be obvious and directly in front of them, but they still may not see its grave necessity.

How Conspiracy Theories Led Me to Christianity

Researching the New World Order and globalism took me down many rabbit holes, one of which eventually led me to the most important realization of all: The Bible is true. It hit me like a ton of bricks to the face. And it changed my life forever—literally! That probably sounds weird to you, especially if you're not a Christian, but it's a true story. Yes, I know, I know: Everybody's testimony about how they came to know Christ is special and unique. You've most likely heard plenty of them before. But mine is really, really unique.

Under Odd Circumstances, I Read Books That Fueled Many Questions

It all started in college. After getting arrested for marijuana possession with some dumbass friends, a county court ordered me to do community service at a nonprofit if I wanted to stay out of jail. To be a smart-ass, I decided to do my “service” at a communist people's library in the college town where I lived. It's not that I was a communist, per se, but it just seemed like a funny thing to do, and reading sounded better than smashing big rocks into little rocks. Plus, even though I wasn't a communist, I was militantly anti-God, pro-abortion, anti-war and all those other things that make naive young liberals susceptible to communist manipulation—useful idiots, as they say. In fact, most of my “service” consisted of reading obscure books surrounded by a bunch of burned-out hippies. And naturally, a lot of the books were ridiculous. Next time, they promised, communism would deliver utopia. It's just that Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Pol Pot and all the other mass murderers did it wrong. But there was one book that would set me on a path that would eventually lead to Satan—and then Christ. Hear me out. At this point, I don't even remember the name of it anymore. It was over a decade ago, and I was a big-time pothead and drug user at the time. But I do remember what it was about. According to the book, the Federal Reserve was a private corporation owned by private banks, and the money system was basically a giant scam. “What?!” I thought. “That couldn't possibly be…could it? How could they possibly hide something like that from us for so long?” In any case, I decided this needed to be investigated further. I even called the Fed in Atlanta to ask if it was privately owned—and it was, by its member banks! As I researched, I learned that the book was generally correct. The proposed solution—have Congress nationalize the monetary system and print its own currency instead of paying interest to private banks on the currency they create through the Fed—was perhaps flawed. But the general outline of how the Fed worked was essentially true: It was a scam of monumental proportions.

I came to the conclusion that each one had some truth but that these religions were primarily tools of social control.

George Bush’s New World Order Speech Led Me to Research the United Nations

This newfound insight into the monetary system led me to investigate many other topics. Eventually, I came across the so-called New World Order. Then-President George H. W. Bush famously declared in a State of the Union that Desert Storm was part of a “big idea, a new world order.”“We have before us the opportunity to forge for ourselves and for future generations a new world order, a world where the rule of law, not the law of the jungle, governs the conduct of nations,” he said, alluding to global law. “When we are successful, and we will be, we have a real chance at this new world order, an order in which a credible United Nations can use its peacekeeping role to fulfill the promise and vision of the U.N.'s founders.”A lot to unpack in that statement. A credible United Nations that would use its “peacekeeping” forces to impose the vision of the U.N.'s founders? At the time, I did not know much about the U.N.'s founders. But the more I studied, the more troubling this became. Joseph Stalin's regime sent a monster named Vyacheslav Molotov. America sent Alger Hiss, who was later convicted in federal court for lying about his role as a Soviet agent and spy. Those U.N. founders? Is he mad? On September 11, 1990, a few weeks after the invasion began, Bush made similar remarks before a joint session of Congress. “Out of these troubled times, our fifth objective—a new world order—can emerge,” declared the late president, who, like his son “Dubya” and even John Kerry, was a longtime member of the bizarre Skull and Bones secret society at Yale University. What was with that phrase? It kept coming up over and over again. Weirdos like former Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who wrote the infamous National Security Study Memorandum 200 calling for imposing drastic population control policies on poor countries, seemed to parrot it all the time.

After Hearing So Many Politicians Say It, I Had to Know—What Is the New World Order?

Of course, it wasn't just members of the Bush crime family or Republicans who were peddling this. Leading Democrats are on the bandwagon too. Joe Biden has repeatedly touted the New World Order in public speeches. And on April 23, 1992, Biden even wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal headlined “How I Learned to Love the New World Order.” In it, he proposed that America should “breathe life into the U.N. Charter.” Then-President Bill Clinton used the same exact language as Bush. “After 1989, President Bush said—and it’s a phrase I often use myself—that we needed a New World Order,” Clinton famously declared, echoing countless others around the world and across the United States. It was obvious that there was some kind of agenda here. The question was: What is it?Growing up in international schools around the world, I had always been taught to view the U.N. as a benign, if incompetent institution seeking “world peace” and closer cooperation among nations. The more I studied the “dictator’s club” and its freakish drive to build a New World Order, though, the more I became convinced that something nefarious was afoot. These warmongers didn't seem all that interested in peace. Rather, they seemed interested in power. In my final year of college, I came across a mind-blowing documentary that confirmed my darkest suspicions: The Untold Story of U.N. Betrayal. After learning about the atrocities perpetrated by U.N. “peacekeeping” troops to force the people of Katanga to submit to a Soviet-backed dictatorship, it became clear to me that the U.N. was, in fact, evil.

What the Bible Says About the New World Order Resonated With Me, but I Still Wasn’t a Believer—Yet

Years before all this, I had become curious about religion. Having grown up around the world with people of all religions, I decided to investigate what it was they believed. The library had books on just about everything, so I got some on Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Judaism and perhaps a few others. After reading or at least skimming them all, I came to the conclusion that each one had some truth but that these religions were primarily tools of social control.But something kept gnawing at me. The more I studied this New World Order, the more I kept thinking about the Bible. I decided to read the book of Revelation, the last book in the Bible. I'll admit it was hard for a non-Christian with very little biblical background to digest. But one thing was very clear: Diabolical forces and world control went hand in hand. The more I worked on the college newspaper I founded with a few friends, the more I felt that we should at least be Christian-friendly. At one point, I even proposed putting a Bible verse, Leviticus 25:10, about proclaiming liberty throughout the land, in the upper corner of our front page. My two deputies, both proud homosexuals, refused to even consider it. But as time went on, that nagging feeling got stronger and stronger.

Oh my god, the Bible is true. It really is!

My Salvation Hit Me Like a Train—the Bible Is True!

Between the Adderall-fueled late nights, the not-so-infrequent magic mushroom trips and lots of studying about the effort to build a New World Order, my mind kept going back to the Bible. Every once in a while, I would even open a random page of an old Catholic Bible that my Aunt Jackie had given me years earlier. It always seemed to be speaking to exactly the issue that was on my mind. Was there something to this?One day, it hit me like a freight train: Oh my god, the Bible is true. It really is! Holy moly! I quickly ran outside to call my Aunt Jackie, the faithful Catholic who also happened to be my godmother and who had been praying for me to find God for all those years. I must have been speaking a zillion miles a minute because I remember her telling me to calm down. “The Holy Spirit has just opened your mind to truth,” I remember her telling me. “This is what I've prayed for all these years.” She did urge me not to go overboard, but the excitement in her voice was obvious too. Something big had just happened. And there would be no going back—ever. My aunt still rags on me about being a Protestant, but she's pleased nonetheless.

I Continue to Find Truth About the New World Order and Biblical Prophecy

As the years went on, and I studied the Bible in more depth, it became more and more obvious to me that the Bible contained the answers to literally all the important questions in life. Gradually, I began to shed my old beliefs—evolution, fornication, abortion and feminism, for example—as the reality of God's word penetrated my heart, mind and soul. Fear about the New World Order disappeared completely. I've never met anybody else with a testimony of salvation quite like mine. And many Christians still refuse to see the biblical answers staring them in the face about what's going on in our world today. But I know one thing: I thank God every day that he saved a wretch like me. And I pray that one day—if he hasn't yet—he will do the same for you.

What It’s Like Being Jewish in a Small Northern Mexico Town

Back in 2010, when I first heard Rihanna’s “Only Girl in the World,” I felt like the main line—“Want you to make me feel like I'm the only girl in the world”—struck a nerve. Yes, I know what the song’s really about, but the line stuck. In a way, I’d always felt like the only (Jewish) girl in the world. Okay, maybe not in the world, but the only Jewish girl in my small town in northern Mexico. My dad’s Catholic-ish, and after a nasty divorce from my birth mother (who I cut ties with a long time ago, and whose Spanish family was uber-Catholic and uber-conservative) he married my step-mom (who I actually call mom), a Jewish woman from Mexico City. I was raised in a mixed religion household where we always celebrated both Catholic and Jewish traditions and holidays, some out of true conviction and some simply because we were used to it. As a kid, I read the Haggadah every year on Pesach and attended Midnight Mass on Christmas—begrudgingly and mostly for my grandmother’s sake. Despite the mixed religious vibe at home, in the “outside world,” I attended Sunday school and had a huge party for my First Communion (but not bat mitzvah), if only because it was what was expected of young girls of a certain age, social and economic standing in my community. Where I come from, Catholic life plays a huge part in daily life and social events, to the point where I even chose to attend a prestigious Catholic high school despite not sharing the beliefs they stood for. I always knew I wasn’t comfortable with the default Catholic path that had been chosen for me; it wasn’t my truth. I vividly remember sitting at the park where my Sunday school teacher would take us during spring lessons; I’d be that one annoying kid asking “how” and “why” about everything she said. The answer was always the same: “Because that’s the way it is; you gotta have faith.” That answer simply wasn’t good enough for me.

In a way, I’d always felt like the only (Jewish) girl in the world.

I Discovered Ways to Embrace My Judaism, Even When I Felt Isolated

Judaism felt more like my truth: I was not only allowed to question everything but I was often encouraged to do so. Things were never taught as black and white; there’s always a scale of grays to consider. I could explore and discover religion at my own pace instead of there being one absolute way of thinking and doing things. I remember first calling myself a Jew at around 12 years old. I never did this in public, just when I was alone, in my room, daydreaming: “Am I a Jew? Yep. I think I am; I’m Jewish.” I began throwing the word around more and more around my friends and my parents. It wasn’t until I was 15 that I finally decided to fully embrace this: I am a Jew. Of course, this sudden—at least it seemed sudden to most people around me—“change” in beliefs wasn’t always easy. As I said, a big part of social life in my small town was deeply tied to Catholicism. It was an uphill battle for me to be taken seriously. From my extended family refusing to acknowledge my desire to officially convert to Judaism to my father—who doesn’t even consider himself a Catholic anymore—constantly telling me “it is just a phase” I’d get over. Despite all this, I decided I needed to be true to myself. “I am Jewish, no matter what” is what I’d keep telling myself. “My Jewishness is valid, even in a city with this few Jews.” Living in a place where there was no real Jewish community meant I was alone on holidays (the few other Jews would usually travel abroad for holidays), save for my mom and grandma, both of whom had been losing interest in their Jewishness at the same time as I started becoming more interested in mine. I love my family, but it was hard not having a community outside of them that I could share this with. While my town had once been alive with Jewish life back in the early 1900s, there were now less than ten other Jews in the city, and none of them were even close to my age. I stuck out like a sore thumb; everywhere I went, I’d be called la Judía—the Jew.Yeah, I was aware that not everyone meant it in the best way, but I was still proud of it. I loved being different in a way that nobody else at school could. I’d always been in love with the spotlight, both literally and figuratively. I did everything I could to stand out: I joined my school’s show choir and drama club; I joined the Model United Nations team; I’d bake challah every few weeks and share it at school (not to toot my own horn, but everyone always raved about my “Jewish bread”); I volunteered with my high school’s community service brigade; and I ran for homecoming queen my freshman year of high school. At 16, when offered the chance to give a conference about Judaism to some seminary students, I jumped at the chance. I wanted people to know who I was and never forget my name.

I Experienced Antisemitism From My Family and My Community

Turns out, though, that standing out and being different in the way that I was different wasn’t always a positive thing. I’ve experienced everything from covert antisemitic attempts from my very religious aunts trying to make me “see the light” and reconvert me back to Catholicism and good friends trying to sneakily “show me the path of light” by inviting me to any and every Protestant Bible study group and youth retreat, to teachers at my Catholic high school telling me I’d go to hell for negating Jesus Christ as my lord and savior and classmates “jokingly” yell at me that I shouldn’t win the WWII debate in history class because “Hitler wiped away all of” us. The antisemitism I faced was mild and mostly passed off as concern or some other “positive” thing, but it was still very real, and while I usually tried to let it slide and make snarky comments to those who crossed me or questioned my Jewishness—“I don’t believe in hell, but either way, isn’t that where the party’s at anyway? It’s where all the fun people go!” or “Well, the guy missed a spot because I’m still here.”—the negativeness their words and actions carried did have some effect on me. I somehow ended up thinking that because of my less than traditional upbringing, I wasn’t a valid Jew. I constantly felt like I had something to prove simply because I wasn’t someone who had spent her childhood at sleepaway camp, going to shul on the high holidays and had a real bat mitzvah. I did not feel Jewish enough. I found myself regularly trying to overcompensate for this: I started dating more observant people, trying to validate my Jewishness through them. This, of course, never went well: I’d feel left out when they went to temple and shut their phone off for Shabbat every weekend; I couldn’t keep up with their use of Hebrew and Yiddish in casual conversation; and I struggled to remember every Jewish holiday (I now know I was too hard on myself back then; there’s too many to actually keep track of on my own—thank G’d for the Reminders app on my phone). Instead of finding the validation I so desperately sought, the feeling of being “not Jewish enough” was only exacerbated. But then again, when does trying to mold oneself into someone they’re not ever turn out right?

I stuck out like a sore thumb.

I Found My Jewish Community—and Myself

It’s taken a few years and a bit of trial and error to find comfort in my Jewishness and figure out how exactly I fit in the world as a young Jewish woman. I realized that instead of longing for a community that didn’t exist in my hometown, I could instead find one online—that’s the beauty of the internet; there are communities for everything and everyone. I started following Jewish artists, content creators, designers and writers. The pandemic helped this process, as it forced communities and congregations to go fully online and fully remote—finally! Little by little, I started finding my people—my tribe, if you will. My Jewish friend circle grew and with it, my knowledge about all things Jewish. In a way, it felt like finding home.Somewhere along the way, I started writing for a Jewish media site, which opened a whole new set of doors and brought some amazing new Jews into my life, some of whom I have shared experiences with, some who are showing me the many different ways that one can be a valid and worthy Jew in the world. In this process of spiritual discovery, I have begun to find myself, bit by bit. I’ve confirmed some personal beliefs that aren’t necessarily related to religion but are somehow supported by it. I’ve felt empowered to try new things, new foods and just generally to get out of my comfort zone. I’m slowly, but steadily, finding my place in the world as a Jewish woman and discovering how to navigate my Jewishness in a way that isn’t tied to my mom’s, my friends’ or my partners’—in a way that’s entirely my own.

Why I Left the Catholic Priesthood

Looking back, it is difficult to put into words what it was like to leave the Jesuit order after only a short stay. What I can tell you is that it was one of the most formative and influential times of my life. What I can also tell you is that when I left, I was certain that I had been there for the right reasons and certain that I still had a long way yet to grow. The lessons in patient trust that I learned there remain. I forget them from time to time, but the essence of what I was striving for—to live a life dedicated to improving the lives of others, to give voice to those unseen and unheard—remains deep, deep within.I am certain that had I been born in another country, or under the auspices of another religious tradition, that I would have found my way to another way of giving back to my community. I came to the Jesuit tradition because I grew up Catholic—forced church outings with the family, stuffy starched shirts for holidays. I was by no means a religious person. If asked, I would say, “I was raised Catholic,” a clean way of signaling that I was forced by my family to do Catholic things, but I certainly never went to church on my own. We were not a terribly religious family, but we had a tradition, which provided a lens through which I could imagine trying to live a life for others. When my high school and college history studies inspired in me a deep concern for my community and filled me with a desire to find an outlet for helping others, I turned to this tradition.

I felt deeply that something had to be done, and done now.

College Didn’t Offer the Education I Wanted

I had the great fortune of encountering fabulous and daring teachers in school, who wanted us to explore, read and gobble up every drop of knowledge we could find. Through this process, living in a world of privilege, excommunicated from reality by the manner in which I was raised, I discovered, rather naively, that the rest of the world did not live as I did and, even worse, would never be presented with the opportunities that I had. This angered me. I felt deeply that something had to be done, and done now. Everywhere I turned in college seemed dedicated to an idea of self-absorbed consumption. “How do I afford to live in fancy oblivion?” It was only the voice of a distant past in my life, a tradition long forgotten, that helped me find another path. Religion made it OK for me to walk away from material wealth and the desire for a job that gave me nothing but a paycheck. It filled me with the hope that I could one day actually help people who actually needed help. And so it was, in the most circuitous of ways, I found myself learning about Jesuits, an order within the Catholic machinery that sets itself—or seems to set itself—apart from the rest of the priesthood, dedicated to a proposition that a life worth living is a life in service to others. This tradition had been there, in the background of my existence, for a long time, but until then, I had mostly ignored it. Now, fueled by a desire for change in the world, I began to reach out. When college ended, and others were scrambling to find internships or jobs or pay their rent, I was packing my bags. Through contacts from my childhood and new Jesuit friends, I had made arrangements to live and work at a school in Quito, Ecuador. The school was dedicated to teaching the poor and ignored the needs of the wealthy. This, for me, was a dream: to turn the world upside down, to make genuine opportunity a practical and obtainable reality.

Service to Others Changed My Life