The Doe’s Latest Stories

It’s Time to Listen to Gen Z

As a white, straight, female teacher, I don’t have a lot to add to the diversity discussions happening in the country. But my students do. And I feel my job as a human and as an educator (specifically a teacher of English) is to listen to others and to try to understand their stories. Being human, I believe, is about listening and creating structures that encourage free speech and foster empathy. Discussions allowed in this realm can change the world. And Gen Z is already there. I am fortunate to share the insight that I have learned by allowing people to speak and to be heard. I start every class with Good Things, a warm-up activity from the participative curriculum Capturing Kids’ Hearts. Good Things encourages students to find the good in their lives and to practice gratitude. Likewise, it fosters community. I adopted this practice from teaching at an earlier school and have found it, of all the classroom practices that I employ, to have the most impact. We so often ask or expect people to discuss sensitive, intimate topics without first establishing a connection. Then, invariably, we get upset when the conversation ends in turmoil. In order to feel comfortable discussing uncomfortable or complicated topics, people must feel recognized and acknowledged. Sharing your thoughts is a vulnerable activity. People have to know they will be listened to regardless of their opinion. This is why I use Good Things, the best part of my day.

I saw more progress and acceptance at that moment than I had seen towards same-sex relationships for most of my life.

Controversial Subjects for Us Aren't Controversial for Them

Here’s an example. A male student raised his hand to share that he had a crush on a neighbor who had just moved in nearby. The students giggled and cheered and asked him to tell more. He shared that they had talked just a few times and that he (the new neighbor) was going to a different school. I held my breath and quickly scanned the room searching for judging eyes or disapproving comments once the students heard the pronoun of the boy on whom he had a crush. But there were none. Only more follow-up questions and excitement at the notion of falling in love with the boy next door. I saw more progress and acceptance at that moment than I had seen towards same-sex relationships for most of my life. As many youngest generations tend to be, Gen Z is known for being the most socially progressive. But they still inspire me every single day. They unknowingly push me to be both a better teacher and person because I see how much promise they wield. Of course, this extends past mere social awareness. They also bring this power to academic discussions. Like most ninth graders across the country, we read To Kill a Mockingbird every fall, a story about an innocent black man accused of raping a white woman. Sound familiar? Although published in 1960, the themes of guilt, innocence and race still ring very true—too true—today. Many people around the country deal with race by ignoring it. However, that is not a privilege afforded to others. The truth of racial inequality often makes people very uncomfortable. And so, to cope with that discomfort, they don’t talk about it. That is not an option in a ninth-grade English class when the book we’re reading demands it. But, if a classroom community has been formed, there is at least some level of trust between the students. A structure and a way of talking need to be in place in order to discuss any sensitive topic. In our discussions, for example, we make a group list of adjectives acknowledging how some people might feel when talking about race (scared, ashamed, proud or embarrassed) and we remember those emotions while speaking. We not only discuss how Tom Robinson’s family must feel, but also Trayvon Martin’s family, and now Elijah McClain’s and many others. Then we hear about the experiences of our own classmates. Racism, which for many may be a distant problem, now becomes very real in my classroom. My students are brave enough to share their vulnerabilities. We listen to each story, with hope, and we develop a little bit more empathy for each person. It would be unfair not to hear from all the voices in my classroom who want or need to share their experience.

We listen to understand.

Gen Z Is Ready for This Moment

My classroom is successful because I work very hard to create a community within it, something that is missing in many of our social spheres. In this space, we talk about what listening is like and how to object to an idea, not to a person. We do activities that promote different perspectives and have discussions where every voice matters. Being able to have a meaningful discussion is so much more than just listening in order to respond. We listen to understand. And we know how to separate what they’re saying from who they are. So often when I hear of the strife and close-mindedness of people in power, I wonder if they wouldn’t benefit from sitting in a freshman year classroom for a week. It would behoove those at the top to hear about topics such as race, gender identity, social status, immigration and the like from voices who may or may not be squeaking just out of puberty. They have things to say. Their voices, and voices everywhere, deserve to be heard. No qualifications or accolades are necessary for being human. There is inherent worthiness that we carry with us. The notion that every person is decent gets lost somewhere between college degrees and wealth and color of skin. It is our job, as a community, to make sure our next generation still feels worthy enough to use their voices to create stronger communities than we have left for them.Gen Z already knows what they want to say. We need to create an environment in which they can.

It Was Only a Dream: My Valediction for the Class of 2020

Right when life was starting to look up, a global pandemic decided to shit on the parade. But the parade hadn't even started yet.For my entire educational life, I worked my ass off for a supposed “American rite of passage." Then, one day, it all came crashing down.I couldn't savor the last three months of high school.

I had it all planned out.

I Was Taught to Be the Best

I have two immigrant parents, an autistic brother, and a try-hard persona that always gets the better of me. Ever since I could crawl, I was instilled with the goal of being number one. My dad would always tell me about his hopes and dreams.“Ay princess,” he’d say, “One day we're going to have the cleanest lawn, and you’re going to help me.” Or sometimes the plan would be to start a band called Soldados de Cristo. He’s had a lot of dreams.My dad’s a man of faith, so he always “left it up to God,” but I secretly felt that he had too many great ideas and not enough focus to ever accomplish one. So for the past four years, the pressure to actually accomplish one of my dad’s dreams of being number one has rested on my shoulders.I had it all planned out.Don't even get me started with this whole, “Well, that's life—it's unfair and unpredictable,” or, “At least you're not dead." Because, trust me, I’ve heard it all.Yes, I'm eternally grateful to be breathing another day, and I thank God daily for those blessings, but that doesn't mean my feelings toward losing everything I worked so hard for aren't valid.I deserve to be sad, mad, furious, heated, pissed off and hurt.I was going to be valedictorian.

I was going to be valedictorian.

My Message to the Class of 2020

I planned to start writing my speech in April, so that by June it would be perfect. I would open with a dumb joke or quote: "A great philosopher once said 'Started from the bottom and now we're here.’” People would laugh, or maybe just my friends, because they know who Drake is. I would recall the life-altering moments I’ve had with teachers and staff. I’d slip in a joke about how I won’t miss the school lunch, but I might miss the lunch ladies.I would say something about how, traditionally, people say that life begins right after high school—but that I think this whole time I've been living, breathing, savoring, experiencing existence. Then I’d get all riled up and say that we beat the statistic, the one that says little brown kids won’t get further than their sophomore year of high school. Or won't make it to a four-year university. Or will get shot before turning 17.I'd start to tear up as I ask my parents to stand in front of the crowd and just say, “Gracias por todo, te amo.” Lastly, I’d talk about all the amazing, crazy, cry-laughing moments I got to experience with such a spectacular group of human beings.Then I’d throw my cap in the air and take in as much of the moment as I could: my friends and the look of adrenaline rushing through their bodies; families and the pure joy in their eyes; teachers and their smug look of, “Yeah I helped do that”; random uncles who probably can't wait to get drunk at the grad party.I would have taken a mental picture—click—of the unforgettable moment of feeling like you accomplished a huge dream that’s not only yours but also your dad's, your mom’s, your grandma’s, your tia's: The feeling that you could take on the world.Except I won't ever get that moment.All the "I would's” have turned into “I won’t’s” or “I can’t’s. I’m stuck in this endless cycle of pitiful self-loathing with no way out. I’m sorry mami, papi, tia, abuela, random uncle, beautiful brown kids—I wanted to do this for you. For us. And, most importantly, for me.For the Class of 2020, this American rite of passage remains just this: an American dream.

Greatness Isn’t Achieved With Participation Trophies

Fair warning: This is going to be blunt but it is also going to be nothing but the truth. As a future teacher, only a year away from my own classroom, I think about what the makeup of a school looks like every day. I do not have many things set in stone yet and I weigh ideas as I continue to learn new things, but there are some things that I do know definitely. My students and I will be a family and I will love each and every one of them like they’re my own. We will have read aloud every single day, no matter the grade. My students will be responsible for themselves and their belongings because excuses don’t get you anywhere. And, oh yeah, in my classroom: We don’t do participation trophies.

Children Can Handle More Than We Think They Can

I think children are naturally built to exceed our expectations. They are born helpless, wrinkly little creatures and somehow they grow into whole-ass humans. That feat itself is uncanny. We bring them into a world that is designed to beat them down and then we give them false ideas of reality—like everybody deserves a trophy—which only makes reality more difficult. I cannot, in good conscience, promote the “everybody’s a winner” ideal. It’s neither healthy nor fair for developing minds, and I will be doing everything in my power to make the experience inside of my classroom as close to outside reality as possible.If I had to pick three words to describe myself and my philosophy on teaching, they would be: responsible, humble, and hardworking. I believe I am the way that I am because I grew up with parents who were choosy with their praise, only handing it out when I went above and beyond their very high standards. And they were not afraid to let me know when I fell below those standards. I don’t mean to sound like I lived with stone-cold ogres, because that’s far from the truth: I always knew I was loved and that they were proud of me. I remember hearing, “You did good, but you could have done better.” Which, in hindsight, is the truth. I figured out very quickly that in order for my effort—in both academics and athletics—to be acknowledged as great, I had to go further. It had to exceed even my own expectations. It’s also why I see the potential radiating off of all the small humans that have blessed me with their presence throughout my education.

We Should Reward Only the Exceptional

So, if the average doesn’t deserve a trophy or a ribbon or a prize, what does deserve recognition? Exceeding the standard set forth. Taking what you’ve been asked to do and going above and beyond, exceeding your own expectations. There is no excuse for being average when you have the ability to be better than that; I’ve never met a student who didn’t have that ability. I often wonder how and why society shifted to being so soft and when competition became so taboo. Imagine this, a class full of third graders playing math Jeopardy! The final scores are calculated and Team A wins. What does Team B do? Do they accept defeat, congratulate Team A on their win, and move on? Oh no, they start crying. “Crying” isn’t really the word. Sobbing is more like it, with a mix of nasty comments, dirty looks and sulking thrown in. Unfortunately, this isn’t a story I just made up. One of my very first solo teaching lessons and I’m standing in front of 15 sobbing third graders, distraught over a game with Christmas-themed pencils as a prize. That was it. My epiphany. That was the day I saw the effects of participation trophies and swore them off forever.

Growth Stems From Acknowledged Failure

You can call me mean or tell me that I expect too much, but I’d argue that I’m playing a huge role in forming young minds who can take responsibility, recognize hard work and exceed the expectations set forth. When everybody gets a prize no matter what, they’re being told that their average or even below-average effort is great and is worthy of recognition. So, when they get somewhere, like a third-grade classroom, where there is a team that wins and a team that loses, they literally cannot handle the defeat. Where are you going to get in life if you sob every time someone does better than you at something? Yeah, exactly. Nowhere. Participation trophies do my students a great disservice by instilling false conceptions of entitlement and greatness. And, honestly, they are incredibly unfair to the kids who actually deserve the trophies. My job as a teacher is to foster growth and you cannot grow when you’re told that everything you do is amazing. That’s just not how life works. So, I refuse to hand out praise and awards that have not been earned by hard work and dedication.

I'm Scared of Small Children: Homophobia, Gender Discrimination and the Home

After several years as a teaching artist in public schools and a private music teacher in homes throughout Los Angeles, I have experienced countless moments of homophobic and gender policing micro-aggressions from the curious and innocent children of well-meaning adults.Kids take in everything around them, and they ask questions, as they should. But when parents bend down to intervene and tell their kid “We don’t ask that,” or “Well, obviously this person is a [fill in the blank]”—or when they don’t intervene at all and leave it to me to straighten out—I know that this young human before me has probably never had a safe place to fully delve into the complexity of gender identity and sexuality. And let’s face it, that was most of our childhoods.

We Need to Teach Children About Sexuality Earlier

Parents often think that their kids don’t need to know about sexuality or gender until they’re “old enough,” which is an unfortunate myth of privilege. Even if parents do explain the complexities of gender and sexuality once or twice to their kids, if the kids don’t have places to practice that knowledge (aka friends with those complexities), they won’t retain it. (Which is pretty normal.)I surround myself with many queer and gender-variant individuals, and sometimes I forget that the rest of the world is not a gender-fluid mob of nonbinary vernacular and love. Many of the families I’ve grown to know over the years make obvious and loving efforts to bridge this gap, but that’s not always the case.There might not ever be a perfect way to handle those awkward moments, but silence and disassociating are not only not perfect, but they’re also detrimental. After decades of experience, I can tell you that those little innocent moments of questioning often turn into the next natural step of social and emotional development for young people.

It might be helpful to also address the fact that transgender or nonbinary individuals are at greater risk of being bullied, gaslit and harmed.

Parental Priorities Have to Lead the Way

I am using the term "discrimination" differently from the usual sense we’re familiar with in racist America. When an individual uses discerning discrimination to analyze a context—or in my case, how my gender identity relates to theirs—they are trying to understand one thing from another. It’s a very binary process, especially in terms of gender. Young people are entrenched in these processes for many years, across various stages of development.During these steps, their brains are trying to consolidate information and categorize it. If you explain to a five-year-old that their piano teacher has a romantic relationship with someone who they call a partner who is female-identifying, and that their piano teacher does not use the gender pronouns “he” or “she”, but instead “they,” you might need to explain the same thing to them again in a matter of days or weeks or months—all along the way adding details about life that they’ve figured out since then.Or you may need to use the example of a cisgender family friend, and their romantic partner and pronouns, but reinforce that the differences at hand are good, making life more interesting and meaningful. It might be helpful to also address the fact that transgender or nonbinary individuals are at greater risk of being bullied, gaslit and harmed.As it is with all things in our world, every family prioritizes essential discourse differently. In contrast, when I enter an educational space as a teacher, I become a social worker, moderator, learning development assessor, content curator, caretaker and—hopefully—the holder of a safe space. No matter what type of students I teach, sexuality and gender can serve as more ammunition for bullying. Whether it’s loud or nonverbal, bullying effectively disrupts growth in the individual and the collective.

I bet our parents wished that they could have provided us more support in our education, too.

Stronger Communication at Home Would Be a Game-Changer

I recently completed my master's in education. One of my 13 colleagues was similar to me in that he also has an older sibling with disabilities who regularly had Individual Education Program meetings throughout his public school education. IEP meetings are held annually and are mandatory under the Federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.My colleague and I both interviewed our parents about IEPs, and they felt that IEPs should be given to every student—not just students with disabilities. It was such an interesting coincidence that both of our parents think this same way, almost two decades after their last public school IEP meeting. My colleague, who also happens to be younger than his sibling with disabilities, probably experienced some of the hardship that I experienced as we both watched our parents and sibling navigate a world filled with ableism, and an education system often inadequate and underresourced for students who learned “differently.”I bet our parents wished that they could have provided us more support in our education, too.This bit of information not only to brings more attention to the struggle that individuals with disabilities face throughout their lives, but also how vital interactions are between a student’s family and education support team. If there was a cultural and systematic vehicle—like an annual IEP— for each individual student’s education support team to gather around and put together a comprehensive plan for them, educators like me wouldn’t have to be the sole voice teaching students, fellow educators and parents how to use educated discernment when addressing gender and sexuality.For special education teachers and their students, one of the great side effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is that parents and guardians are more able to attend their IEP or education support meetings now since every single meeting is virtual and more flexible for working parents.I truly believe that the gender policing and homophobic micro-aggressions I’ve experienced from students would be nearly non-existent if there were stronger lines of communication between school and home, teacher and family, as well as more support overall in public school. Families need the support of educators and administrators, while educators need the behavioral and social support of families. When we build better support for our students, we build better support for the people trying to raise and educate them.Until we create new tools, I’ll still carry my fear of children’s words, and miseducation their parents give them.

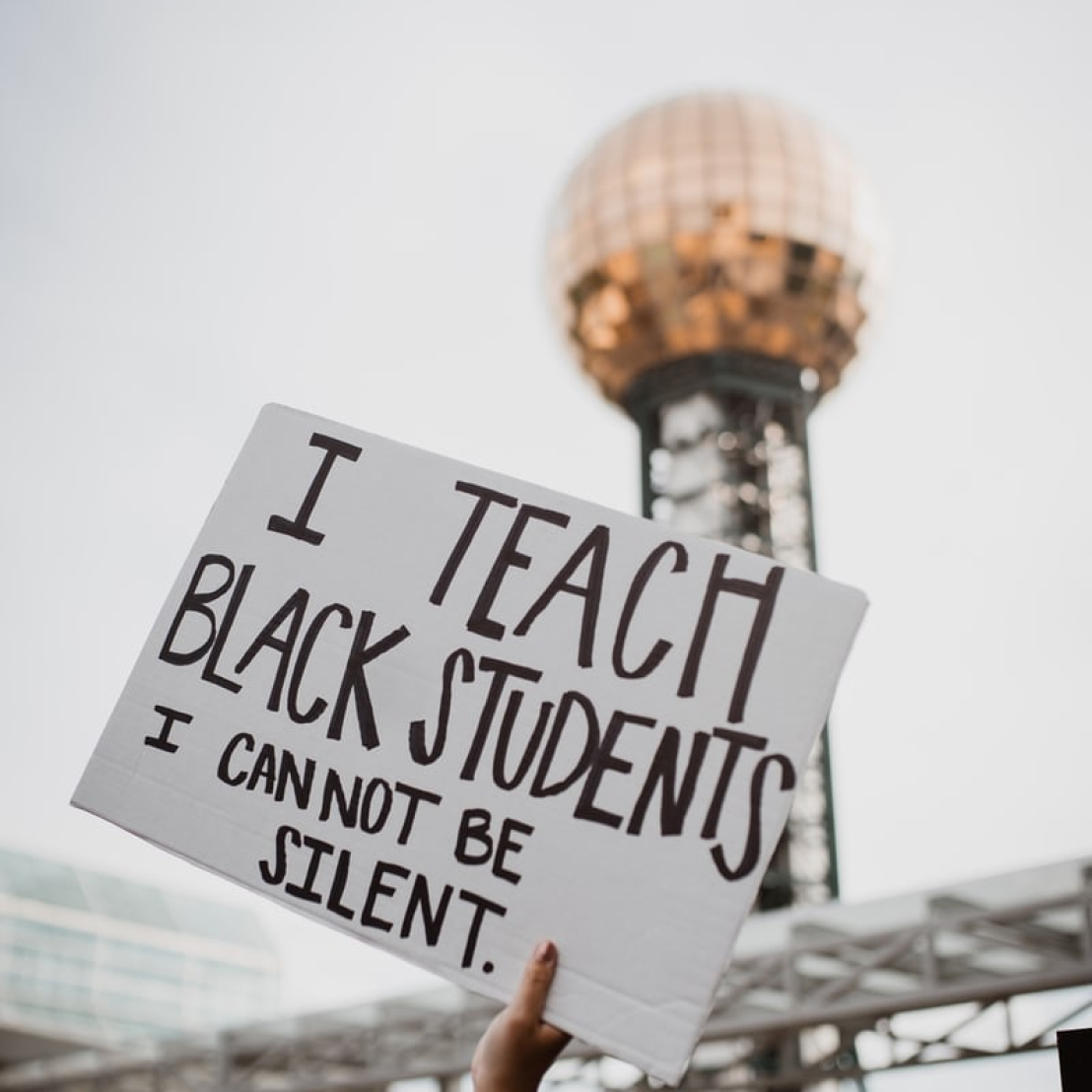

I’m a White Teacher and Coach; I Need to Do More for My Black Students

The morning after Trump was elected, the small football team I coached at the time traveled up to Fontana, California, near San Bernardino, for a playoff game. Our team was made up of students from Compton, Watts and Huntington Park. We had only lost one game the whole season and were expected to win it all. At worst we thought we’d make it to the championship game.When we got off the bus in Fontana, there was a heaviness in the air. You could see it on the faces of the whole team and the coaches, too, but everyone mostly kept to themselves. I thought about addressing the team, but what could I say? I didn’t even know how “political” any of the players and other coaches were.We were up against a team of predominantly white players from another town. From the start of the game, I could tell there was something off with the team, and I knew it was going to be a struggle. As it went on, we all got more frustrated. There was tension brewing on the field and on the sidelines that felt personal, but no one was naming it.We ended up losing to a team we should easily have beaten.

We ended up losing to a team we should easily have beaten.

My Students Have Been Dealing With Racism Their Entire Lives

At the end of the game, a white parent from the other team got up in the face of our coach, who is a black man, and yelled at him: “That’s right! Trump, baby! Get used to it!”No one rebuked him. I’m embarrassed to say I was more concerned with diffusing the conflict rather than doing what needed to be done, which was to address a clearly racist comment. Trying to keep the peace, I walked to the other side of the field to get our coach and we moved on with the day. Just like that.I was scared for the players on the team, that this was going to be their new reality. I was scared by this newfound brazenness of racist white people, and what effect it would have on these kids.What I later realized was that this was my new reality—as a white man—not theirs. How many times had my players heard things like this before? Too many times to count, I’m sure. If this was new to behavior me, it wasn’t to them. I think about what would happen now if the same moment occurred again now, less than four years later. Would that person still have the gall to make a comment like that now? Would I react differently? Would someone else step in and say something too?The only thing on my mind that morning was what had happened the night before. How could everyone not be talking about this right now? Was I the only one this outraged?This felt like the greatest injustice of my life. The fact is that it didn’t matter to our players who was in the White House. Policies may vary between presidents, and with those policies come both positive and negative outcomes—especially depending on your perspective. But I was completely missing the point.

It's Time for Me to Do My Part

In reality, Trump’s election really represented just another failure in a long line of failures for America (i.e., white America) to show these kids that black lives matter—that they matter. In wondering if my students and coaches were “political,” I was missing the glaring fact that their lives were inherently political, as our country had been waging war on black bodies since its inception.Whether they were civically engaged or not was beside the point. America had been using their blackness as a political tool for their entire lives, without care of whether or not they chose to “opt-in.” The systems of power that oppress people of color have been in place for centuries in this country. Does it really matter who is at the helm?The past seven years being a self-described “woke” white teacher in a school with predominantly black and brown students have lulled me into thinking I’ve been doing my part for them. The past few months, with Black Lives Matter causing much-needed change and conversation in this country, have opened my eyes to the reality that I haven’t.Being “anti-racist” is an action and it requires more from me. Systemic white supremacy is responsible for so many of the obstacles my students face daily. How have I actively used my whiteness to help change that? How often am I putting my body on the line, speaking up when it might be uncomfortable, or promoting black businesses and voices intentionally? It’s almost like I forgot about my whiteness—the very indicator of white privilege.My students deserve better.

We Had 48 Hours: How Teachers Transformed the Education System Over a Weekend

I went back to my classroom in late April, a month after our world exploded. Entering the building, I felt the surge of morning adrenaline that usually precedes a day of teaching, but the vacant hallways and absent cacophonies of voices were a sober reminder that this wasn’t a typical morning. No quick footsteps to beat the bell or steam from the contraband coffee that students snuck into their seats. The memory of all that vibrant classroom life imprinted in my mind pained me like a phantom limb.Picture this: You’ve been in your career for over a decade. While there is incremental evolution in your field, the comprehensive, systemic change it really needs often feels infuriatingly impossible. If you know anything about education, you know that it’s as weighed down by bureaucracy as just about anything. March of this year now feels as far off and remote as those Chernobyl photographs of life frozen in 1986. Those first weeks of that month were marked with the early stages of the pandemic and rumblings of the possibility of remote learning. While our curiosity was piqued by the rumors, no one truly believed we’d actually be doing it. Before that fateful Friday the 13th, when lockdown went into effect, my office sounded like a carnival of uncertain birds. “Who knows? We might go remote, but I doubt it.” “Do you even think that’s possible?” “What would that even look like for teachers and students?” “It’s not going to happen.” But it did happen. What’s worth noting about my district, as opposed to many other districts around the country, is that we were notified on a Thursday night that we’d be going remote the very next Monday. While other districts added buffer weeks onto their spring breaks in order to prepare for this change, we navigated a paradigm shift that was beyond all of our imagining just a week before—all in the span of a weekend.

We had 48 hours to figure out how to do it all differently.

Bureaucracies Don’t Become Nimble Overnight

We spent that final Friday of in-person classes navigating a complicated balancing act of staying calm to quell our students’ panic while simultaneously grappling with the frantic unknown of the sweeping transformation we had just 48 hours to pull off. Students deserved to see that we as human beings could be resilient in the face of an unexpected challenge, but that it is was also okay to feel anxiety, to feel fear. In each class there was a mix of calm and frenetic direction; I told my students to take everything they could home.And then we had 48 hours to figure out how to do it all differently.Two days to plan and fret and fret and plan. Two days to not only prepare for a radical reimagining of our teaching careers, but also to process what it meant to be in a global pandemic. What would it mean for my family? What would it mean for my son in first grade? How would I do my job, teach my students and facilitate my child through the content his own industrious teachers crafted for him?Teachers are consummate problem solvers and world-class improvisers. I quickly realized that we’d be inventing things as we went along. Even though we were blindsided by the timing and pace, there was always that underlying sense of our fine-tuned ability and gumption: If we can teach amongst lockdown drills and endless budget cuts, we could do this. And we did.

How to Revolutionize American Education in Two Days

That first day we only had time to test out new tech tools, collaborate with our colleagues via Google Meet and Zoom, and prototype what we hoped would be a successful first week of online curriculum. As with most prototypes, there were glitches. Before we left our brick-and-mortar setting, the mission we were given was loud and clear: recreate the school day, with the same levels of work and rigor you would offer in a normal in-person class period.How naive we were. Oh, the missives I wish I could send back to my first-week self.My teaching teams and I created what we hoped would be rich, meaningful and engaging content that still challenged our students and maintained their baseline motivation to learn. Without that intangible magic of the in-person interface to rely on, we had to engage in some content design acrobatics, although we didn’t quite understand how acrobatic we’d really need to be.From the outside, it may have looked like we had one single problem to solve—how to teach classes via video chat—but there were an endless number of complicating factors: How to meet the needs of all of our students with special educational needs and plans. All of the students acting as stand-in facilitators for their siblings. All of the students with jobs. All of the students grappling with mental illness. All of the teachers with underlying health problems. All of the teachers with children at home, whose learning matters as much as their students. All of this while we are about to have our salaries frozen, if not potentially cut for the second time in over a decade. (And again Betsy Devos has dug her heels in on diverting public CARES Act funds to private schools.)

Oh, the missives I wish I could send back to my first-week self.

Teachers Tried Hard to Fix Things; We Still Failed

On Tuesday, March 17, it all began in earnest. By the middle of the day, I’d received a message from one of my more vocal and cynical students (who I love for it) bemoaning the workload and claiming she’d spent more time on schoolwork in our first day of remote learning than she did on a regular school day. Regrettably, I didn’t believe her at first, which violates all of my teacher’s instincts. I think in those early days I felt so determined to perform under the pressure, and that my snap judgments had to be right the first time, that I forgot the most essential rule of teaching: Listen to your students. After hearing from more stressed-out students, I knew remote learning version 1.0 was not going to work. Deflated and defeated, I slid my chair back from my dining-room-table-turned-desk, head in hands, heart overloaded with the weight of this colossal task.Thankfully, I snapped out of it. The stress of those hectic 48 hours hadn’t taken away my ability to reflect. Our plan to replicate a normal school day was untenable—in fact, the pressure it levied on our students uncovered a new hierarchy of needs specific to remote learning. Perhaps this will be one of the most important lessons we’ll take away from this experience.With each mounting Zoom call, I realized our initial version of direct instruction and discussion was no longer feasible and was no longer priority number one. Test scores and grades had started to seem abstract and tertiary. In these same moments, I realized it wasn’t all that gorgeously-designed instruction that would keep us afloat, but the deeply entrenched relationships we’d cultivated painstakingly throughout the year.Relationships kept students checking in. Relationships persuaded them to hop on Zoom calls when they were needed. Relationships encouraged them to trust us and trudge through new types of work.But there were times when relationships weren’t enough. By the first Thursday of remote learning, I started to notice a handful of students who weren’t answering the Google Classroom question of the day or submitting that week’s piece of writing or shooting me emails to ask questions. It hadn’t even been a week and I was already seeing how quickly and easily it could be for them to slip through the cracks. My anxiety swelled.

We cannot simply drift back to sleep.

Real Change Means Learning From Those Mistakes

The universal teacher mantra is, “Am I doing enough?” Yes, it’s phrased as an anxious question instead of an affirming statement, but we’re teachers—we want to learn and grow right along with our students, and we know that questioning our world is the swiftest path to wisdom. We have high expectations for ourselves and we don’t need any underfunded, ill-designed evaluation system to force this question. But with these first-week epiphanies came an intensified cycle of asking myself this question—a cycle that dominated all of my decision-making as we anxiously awaited news about the fate of our remaining school year.It was only when we knew it wasn’t an extended spring break, when we accepted this was the reality of this semester, that we perhaps fully understood the magnitude of what we’d just accomplished. That first week following Friday the 13th wouldn’t go down as a blip or a Band-Aid or a patch job. The decisions we made in that brief time would affect the trajectory of the rest of the semester, and most likely the school year to come.Now, as we look forward to a year beginning during this pandemic, I sincerely hope that we don’t take the lessons of this past spring for granted. March heralded a paradigm shift, perhaps one that education desperately needed. We cannot simply drift back to sleep.I wish I could end this article on an optimistic note about what this country will learn from this past spring. Sadly, I cannot. I do know, however, that at the grassroots level, this country can depend on its teachers to continue to problem-solve and innovate in the face of whatever is slung at us. Even if we only have two days to do it.

What It’s Like to Be a Female Coach in a Male-Dominated Field

I’ll never forget my first day as a coach. I was 23 years old, right out of college and exhausted from my first nine-hour day as a teacher, when I first stepped foot on the beet-red crumbling synthetic rubber track of a Maryland college. My male assistant coach looked at me with undisguised shock. “You're the head coach?” he asked, astounded.After that not-so-warm welcome, he peppered me with a series of questions, trying to gauge my skill set and experience. “Oh, so you ran in college? What are your times? What do you know about mileage? Do you need help? Wait, so you’ve never coached before? Don’t worry, I can help you.” And so it began.

I Was a Successful Runner; There's No Question I Should Be Coaching

I was a competitive runner from middle school all the way through college, and by the time I started coaching I’d already been through three successful programs, two club teams and three years in Division I. I also had experience with two strong female coaches—one in high school and the other in college—who produced both personal and team successes year after year. Even though female coaches were few and far between, they both inspired me to follow in their footsteps.I was the only female coach for both cross country and track and field that year. I don’t think I fully realized how differently I’d be treated as a woman—criticized, critiqued, questioned and treated like I was dainty and fragile—until track and field season that spring. As a new teacher and coach, I didn’t want to step on any toes, so I did what any other first-year coach would do: Stay quiet and listen to the advice from other male coaches, even though I didn’t always agree with them (and they were often condescending). My male colleagues often felt the need to explain things to me as if I were completely new to the sport. Afterward, they’d reward my patience with a pat on the shoulder, like they'd helped me understand a colossal idea I wasn’t capable of figuring out on my own. They called me “sweetie” and “honey.” During practice, they’d talk over me, and any advice I gave our runners would get rephrased and re-explained as soon as the words left my mouth. This went on for years.

Anything that was considered to be a challenge to the male coaches’ authority—or really any change, in general—was not allowed within the program.

You Have to Work Twice as Hard When You're a Female Coach

Along with my desire to push athletes to excel, I knew I needed to literally and figuratively go the extra mile to make my mark as a credible coach. And I did—our teams consistently improved each year I was in charge. More of our athletes qualified for the state meet, and, after graduation, more continued on to running careers at the next level. As athletes began to respond to my coaching style, they started to see more success, pushing themselves more in practices and meets. The success was infectious. Finally, after four years of six-day coaching weeks, our boys track and field team had the perfect day. In May of that year, I was able to see all of the hard work pay off when we won the state championship by half a point. It was the best day of my coaching career so far at that point, even if my male counterparts didn’t support me.Six years into my coaching career, I moved to Colorado for a new job and a change of pace. I ended up walking into a coaching situation where the only position available was as an assistant coach. The head coach had zero running experience when he took over after his daughter started running for the school. On my first day talking with him, I realized that the male coaches here were much of the same as they were back in Maryland. They called my coaching experience into question. My input for workouts, meets and team bonding activities were shot down day after day. Anything that was considered to be a challenge to the male coaches’ authority—or really any change, in general—was not allowed within the program.

Looking back, I wish I would have spoken up sooner.

I Found Out I Wasn't Alone

During the following track and field season, I was one of five assistant coaches to two male head coaches, making me the only female in an authority position for both our girls and boys teams. The head coaches didn’t get along. They were part of what I came to understand as the “Good Ol’ Boys Club”: unmotivated, stuck in their ways and constitutionally unable to agree with each other over anything. They demanded respect from athletes and coaches, yet did nothing to earn it—since they had no experience running themselves. However things were done in the past, that was how they were always going to be done in the future. I often found myself in the middle of arguments where they’d ask me to do something because “you’re female and you’re organized.” After nine years of this, I realized that I couldn’t be the only female coach experiencing challenges from their male peers. I soon found out I was right. A woman I worked with told me about a local support group started by other female coaches. I checked out a meeting and found ten strong, determined, successful women who I could relate to on a personal and professional level. We shared stories, laughed, gave advice and last spring we all went to a coaching conference together. They gave me a voice—I felt more confident to stand up for myself, show my expertise, share my personal experiences and have an opinion. Looking back, I wish I would have spoken up sooner. Trying to be non-confrontational, kind and open to hearing people who have bigger roles than I put me in a position where I wasn’t taken seriously. Despite being silenced for nine years, I’ve learned to not question myself or my expertise anymore. I would love to say that the challenges I’ve faced are an uncommon experience for female coaches, but I’d be lying. I’m proud of myself for having overcome things that most male coaches never have to go through, and for learning what I have along the way. I hope I can inspire future female coaches to stand up for themselves, to use their voices and to realize that they are there for a reason.

Substitute Teaching Will Ruin You. Do It Anyway.

“They won’t listen to me.”I was standing in the middle of the mall, dumbstruck, fumbling. Neither my management training nor radio and stage experience could prepare me for what I had just agreed to. Running into my old high school dean—the one who saved my life junior year by advocating for me and lighting a fire under my ass—hadn’t been on my lunch calendar that day.“They won’t listen to me,” I said again. He pressed on, as undeterred now as a principal as he was as a dean.“You’d be surprised,” he smirked. “You may be the only one they will listen to.”He turned to walk away. “Apply yourself,” he added over his shoulder. “I haven’t been wrong about you yet.”

The road to hell, as they say, truly is paved with good intentions.

Substitute Teaching Is Rough at First

My first class as a substitute teacher at my alma mater was a disaster. Well, maybe “disaster” is too dramatic. Let’s try “distracting.” By dressing far too casually, I’d tipped the authoritative scales into an imbalance I could never recalibrate, especially in front of so many familiar faces. I thought I was being relatable, but these kids—many of whom clocked me from the mall or the radio—saw themselves less as my students and more as my ambitious almost-peers. This cavalier rapport made it almost impossible for anything I had to say to stick.Still, I managed to catch their attention.There was a benefit to speaking the common slang parlance. Instead of resisting it, I leaned into my performance skill sets and radio show prep, finding ways of explaining their present class subject in pop culture terms. It was a rousing success. I had connected! And I continued “connecting” until right around lunchtime when I was summoned to the main office.Apparently, in an attempt to relate (or perhaps over-relate), I’d shared a personal story that triggered two young women to tears as they shared theirs. Moved, I offered to let them stay on in the classroom for their lunch hour and cry it out while I prepped for my next class. What I didn’t know at the time was that: A) I wasn’t qualified (meaning not permitted) to make such a call, as I was not a trained counselor, and B) there had recently been a very ugly scandal that occurred the grade period prior involving a soccer coach and some very illicit interactions with the students.Suffice to say, the school had “measures” in place for these kinds of situations. The road to hell, as they say, truly is paved with good intentions.After word spread that I, a casually dressed novice non-educator, was in a classroom alone with two female students crying, I ended up having to tell my story to the principal and deans. Ignorant of the prior scandal, I plead my case passionately, feeling like I had made a positive, human move with students who came from the same neighborhood as me. I felt like I had actually connected, but the administrators still ended my substituting contract that very day, out of fear of a repeat of the soccer coach incident.“They won’t listen to me.”Before that class, no one had given me any training. The school district was short-handed, and just needed bodies in the classrooms to watch the students instead of actually trying to engage them. They weren’t there to learn, I was told, but to be trained to test well. The entire situation hurt my spirit.

I was terrified.

Still, I Went Back for More

After taking six months off for equal parts soul-searching and self-directed training, I tried my hand at subbing once more, this time in another township. It turned out to be a world apart from before, and one of the defining experiences of my life.This district had a more structured approach to education. There was a mandatory business-casual dress code, guidelines on how to respond to crises, clear support personnel in place for counseling, and skills-based testing for all incoming substitutes. I felt prepared this time to show up for whatever students entered the space.The only issue was that I was now in a township further from where I grew up, so I didn’t know these kids the same. There wasn’t any immediate rapport, and my previous “coolness” factor, I feared, was now lost behind my standards-compliant shirt and tie.My first assignment was an AP calculus class. They arrived chipper, ready and almost eerily wide-eyed to learn. Yet they regarded me with the same side-eye reserved for those on the outside of their circle of inside jokes and witty banter.I was terrified.

They wanted to be seen.

I Finally Connected With Students

But while I took attendance, checking with the kids to make sure I understood and correctly pronounced each of their unique names, an interesting thing happened. Their faces lit up. Their body language shifted. Students, clearly used to years of having their names butchered by subs and regular teachers alike, leaned in and engaged.We blew through the lessons, then, with 20 minutes left in class, I gave them open study. Their faces lit up with questions…for me. They wanted to know about life, the real world, how much of what they were learning would be applicable out there. They wanted to know how they should approach college, how should they dress, what to look for in a job, why I cared enough to get their names right. My favorite part was being asked how to be happy with yourself, even if you’re choosing a path different from your parents’ expectations.These kids wanted to be ready for the world. They wanted to be seen. They wanted to do well. And they wanted validation from me—a stand-in, a substitute instructor, a guy in a tie with a checkered past and no formal education training, but a deep-seated desire to teach others about the world.In my heart, I wanted to give them all the answers they asked for, but instead, I stuck to the script—as instructed. My hands were tied by structure, standards—rules set in place to avoid any unforeseen “occurrences.” I knew that no matter how much I pleaded with the administrators to let me freestyle the lesson plans a bit to connect these kids to the subjects, all they seemed to care about were test scores and collective performance.So, I politely declined my class’ attempts to connect, telling them I wasn’t qualified to give them the answers they were looking for explicitly—I only snuck them into the day’s lessons. I tried to tell them this. I did. I smiled, pleaded with them, tried as gracefully as I could to not give them the truths they so desperately hungered for in their scholastic experiences. But just like I knew, they wouldn’t listen to me anyhow.

How We Can Teach in the Wake of George Floyd

On May 25, 2020, teachers around the nation were sitting in our newly fashioned “home classrooms,” crafting digital lessons for our students. We were looking for ways to navigate the switch from in-person to virtual learning, and wrapping up yet another school year with the usual sense of exhaustion that comes with it. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill. Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes—roughly the amount of time we take in class for our morning warm-up activity. On May 25, 2020, our approaches to education were about to drastically change, and none of us had a clue. In the days that followed George Floyd’s murder, new breath was given to a centuries-old issue, with the help of the 24-hour news cycle. People took to the streets, outraged by the murder and upset by the fact that this particular killing was really only the latest in a long train of white-on-black violence—or rather, system-on-black violence. While we watched from home, we wondered what to make of it all. And, more importantly, we wondered what our new roles in it all must be.

It’s Time to Learn How to Unlearn

Something about this time—and this particular murder of a black man in police custody—is different. Teachers have watched similar encounters before. Some of us have even addressed them in our classrooms. But real action never came. Real urgency for change never took over. Now the movement has put a spotlight on police abuse, but the underlying issue is systemic, which means that the roots of the problem extend far and wide, to institutions beyond the police force that are complicit in American racism. Education is one of them. Teachers must now decide if we’ll continue to be part of the problem, or if we’ll finally use our voices to advocate for necessary change. Right now, many of us in education are embarking on what’s being called “unlearning,” where we work to shed our own personal biases (both overt and covert), acknowledge our own privileges and seek ways to be better allies and partners for our BIPOC friends, family and students. We’re devouring books, articles, TED Talks, documentaries and podcasts to learn about ourselves and others. History teachers are looking at their curriculums and tallying the frequency with which marginalized groups are discussed (and perhaps more importantly, re-evaluating how often those groups are presented as victims, rather than from a position of strength). English teachers are taking inventory of their classroom libraries and their course reading selections to gauge the level of diversity—or lack thereof—in authorship. Many of us are discovering, possibly for the first time, how our whiteness has created so much darkness for others. We are finding answers, only to create more questions.

We Can’t Confuse a Responsible Teacher for a Neutral One

The first college paper I wrote in my undergraduate education program was in response to the prompt, “What makes a morally responsible teacher?” That’s a big question, especially for an 18-year-old who doesn’t know anything about anything. And, frankly, that’s even a big question for a 30-something-year-old woman in her tenth year of teaching. While I was writing it, I tried to think of all the things that led me to an education major to begin with: a deep passion for the material, a drive to share that passion in others, a desire to help students see and achieve their full potential. It all felt so disgustingly cliché. I thought back to the teacher who changed it all for me: my world history teacher. I thought about the qualities that set her apart from the others. I thought about what she taught, and how. I finally decided that a morally responsible teacher is one who creates an environment that provides students with all the necessary information and tools to come to their own conclusions, without the teacher inserting themselves and their personal beliefs into the mix. What I’m realizing now is that I meant “one who’s neutral.” For a long time, I thought I was doing right by my students by keeping my personal opinions out of the classroom. I truly believed that my job was to help them learn how to think, not what to think. As a social studies teacher, I never shied away from contentious topics or debates. I worked diligently to research both sides of every issue we discussed ahead of time, so that I could be prepped and ready to play devil’s advocate, no matter the direction the conversation took. I strove to make safe spaces for my students and taught them to criticize ideas, not people. But reflecting back on some of the debates, some of the conversations, some of the ways students behaved, I find myself wondering whether or not I actually provided a safe space for all of my students. Did I challenge the unenlightened opinion enough? Did I call out racist or sexist comments for what they really were? Did I call those comments “racist” or “sexist”? Or did I skirt around the issue with vague, unhelpful, “neutral” language? Did I sacrifice a learning opportunity out of fear that I wouldn’t be seen as “politically sensitive” to reactionary ideas, even if those ideas were based on hatred and fear? I honestly don’t remember.

Change Can’t Happen From Inside Our Comfort Zones

This moment was made for social studies. Geography curriculums include units on cooperation and conflict. World history courses often spend quite a bit of time on “the long 19th century,” during which the basic ideals of democracy and the people’s relationship with their governments took shape. American history courses are centered on the evolution of our democracy, and the protest efforts that have created the world we live in today. Economics courses are founded on the basic questions of distributing resources. Government courses are designed to educate students on civil disobedience, the role of government and how to be an active and engaged citizen. Social studies, as a core subject, really is the place to discuss the marginalized communities. Our classrooms and our instruction need to start reflecting that more intentionally. We can no longer let ourselves off the hook and justify exclusion for “politically correct” reasons. As we think about what we teach, we are also beginning to have uncomfortable conversations about how we teach. Maybe the morally responsible teacher isn’t neutral. Maybe teaching is a political act. Maybe one of the best things we can teach our students is how to be fallible—how to recognize the limits of our own knowledge, how to seek to push our established boundaries, how to know when you don’t actually know anything and what to do next. Maybe the best lesson we teach is one of unlearning.

I Teach to Love

Teachers are a special kind of human. Ask one why they chose to teach and most will tell you that it wasn’t their choice—teaching chose them. That’s my story. I’ve known since kindergarten that teaching was the path I was made for. It was the path that I needed—not just wanted—to follow. Teachers don’t just teach, they also love. When we walk into our classroom every day, our mission isn’t to squeeze every drop of information into our student’s brains before we send them home for the day. Our mission is to show every student that someone loves them, cares about them and is there for them every single day—all while still squeezing in every drop of information we can. It’s absolute insanity, but we love it.

You Don’t Learn to Be a Teacher; You’re Born to Do It

Since the days of playing teacher’s helper in kindergarten, I’ve known that teaching is so much more than just passing on information. Every year since eighth grade, I’ve been in an elementary classroom in one form or another, whether it be independent studies, internships or field experiences. To be honest, I’d never sat down before and reflected on my true intentions with teaching or questioned why I even wanted to teach in the first place. I think back now and go, “How in the hell was that never a train of thought?” The answer is quite simple: I have no clue. It was always just something that I knew I needed to do.Last year, I started teaching fifth grade—terrifying. I’d only ever had kindergarteners and third graders before. Fifth just seemed like a whole different ball game. It ended up changing my life. I lucked out in terms of mentor teachers, schools and students. My very first day, I walked in and it was like walking into my home. Throughout the semester, I had to write about both my solo teaching lessons and on my experience as a whole, which led me to truly reflect on myself and why I was there. Before my semester in fifth grade, I might have said that I wanted to be a teacher because I really like kids, or because I think it’s super badass that I get to play a role in forming the next generation, or because I just really liked school.

Teaching Taught Me How to Love

These things are all still true, but now I have a different outlook. I want to be a teacher but it's not just because I am a teacher. It’s true, my job is to throw all of the necessary information that I can into the heads of every student that walks in my classroom, but I also get to be their friend, their counselor, their encouragement, their structure and their safe place. Most importantly, I get to love them. There wasn’t a single day that I walked into that fifth-grade classroom where I wasn’t so excited to get to love all 30 of those kids. Fifth grade taught me that the word “teach” is synonymous with the word “love.”I’m not a mom, but I can imagine what it feels like to look at a small human and just be filled to the brim with pride and emotion, because that’s what happened three days a week for a semester—walking in to see these 30 faces turn, look at me and smile. I was reassured every single day that teaching is exactly what I need to be doing. (I should add that I’m generally not an emotional person, so I'm always a little taken aback when I have conversations with students and have to resist the urge to hug them and tell them how proud I am of them.) Since that fifth grade class, I’ve only had one field experience (kindergarten again), and it was cut short by COVID. But I noticed a change in myself, walking into that new classroom with the insight gained from the last one. I knew that not only was I there to learn from the students and my new mentor teacher, but also to be another adult in the room that got to love them all day. Another adult that greeted them with a smile each morning, gave them a high five as they went to lunch and hugged them at the end of the day.

Teaching Is a Rough Gig; Good Thing It’s Not Our Only One

I often feel like teachers are overshadowed by all of the negative and controversial parts of education—the standardized testing, unfair pay, common core, budget cuts, student performance and whatever bullshit the Secretary of Education is pulling at that moment. Teachers can get so tangled up in all of the education talk that they don’t get recognized or appreciated for all the things they do, and all of the jobs that they have. Teachers aren’t ever just your child’s teacher. Teachers are superheroes. And do you know why they put up with all of the negativity, the low wages and the constant kicks in the face that educational programs typically deploy? Because their love for their students outweighs all of it. I have never met a teacher—and I’ve met a lot—who wouldn’t give the shirt off their back to any one of their students if they needed it. Teachers are everything their students need them to be on any given day. Sometimes they know your child better than you do.Teaching has forever changed me. It’s a lifestyle. It’s a sacrifice. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But teaching is, above all else, love.

Gen Z and Social Media Are a Bomb Waiting to Explode

We all know someone on social media who could use a little literacy. It's not an uncommon sight for me to scroll through a sea of posts and find several that are highly questionable. I try to take the time to educate the person who posted—or more often reposted—why they should’ve taken a more critical eye to the material. Recently, I’ve noticed an alarming trend among posts with questionable material. More and more often, the person reposting is not an elderly relative or distant "friend" from high school. They’re my former students—people who I know firsthand have the ability to critically analyze their origin, purpose and content, because I taught them how to do it. People who once showed a great aptitude at examining historical documents are now carelessly posting dangerous falsehoods. Admittedly, I have more questions than answers. How could this skill not transfer to contemporary documents? Am I at all responsible? What could I do differently in my classroom to put an end to it? And why are technologically savvy younger people just as likely as older people to repost misleading content?

The New Generation Gap Is Between Cable and Social Media

While I do not have all the answers, I do have a lot of experience with millennials (I’m one myself) and Generation Z from my 16 years teaching high school. Like generations before them, they’re tricky to label with an all-encompassing description. In one of my undergrad political science classes, my professor referred to the generation of people who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s not as Generation X, but instead as the Microwave Generation. He argued that because they had grown up in a world where they could have food at the press a button, they were prone to demand instant gratification when it came to politics—a problem for a system intentionally designed to be slow and deliberative. The idea that a single technological advancement that changed how they saw the world certainly struck me as unique but also problematic, as technological advancement grows more rapidly with each year. But if you pressed me, I’d say that millennials are the cable generation and Gen Z are the social media generation. Cable and social media have revolutionized the way people communicate. Since both generations grew up in a world where communication was rapid—if not instantaneous—it would also hold true that they favor posting material online quickly. The ability to share content created by someone else—who in many, or even most cases, is a stranger—complicates the ability to critically analyze its origins, so much so that many people don't think twice before hitting the share button.I'm not saying younger generations don’t think before they post. In fact, I think they’re the most intentional about how they present themselves on social media. I remember being baffled years ago when my classroom full of seniors taught me about their private “Finstagrams.” It was the first time I felt like an old lady compared to my students, trying to wrap my head around why anyone would need an account that only close friends followed to post embarrassing material. "If you don't want people to see what you post,” I remember asking, “Why would you let them follow you?” That was decidedly the day I officially became a senior citizen in their eyes. And it was also the day that I started to question the effectiveness of media literacy education for people who saw social media in completely different terms from those designing the lessons.

Gen Z Knows the Difference Between “Feeling True” and “Being True”

Last year, I read a Forbes article that argued that for Gen Z technology was not an addiction but instead an extension of themselves. I’ve remembered this piece as recent events have turned my own social media feed into a virtual nightmare. People from all sides of the political spectrum are sharing and retweeting content from the furthest depths of the internet, without any regard to the factual accuracy of the material. Again, the demographic sharing the most problematic content is younger. The day after President Trump walked across Lafayette Square and posed in front of St. John's Church holding a Bible, after protesters had been removed by Capitol Police using flash-bang grenades and pepper spray, my feed was inundated with one particularly alarming post. I'm sure you saw it too: side-by-side images of Trump and Hitler both holding Bibles. The photo of Hitler however was a very clearly—and, in my opinion, poorly executed—fake. Yet there it was being posted, shared and retweeted over and over again, often without any words or explanation from the person posting. Each time I saw the image in a post, tweet or story from a former student I pointed out that it was Photoshopped. The response was often the same: They didn’t know it was Photoshopped, but they were still okay with putting the image out there because it represented what they felt was a truth: that Trump’s actions were that of a dictator. For me, this confirmed the assertion that Gen Z does in fact see technology as an extension of themselves. They’re less concerned with posting facts because they don't see that as social media’s purpose. For them, social media is an extension of their thoughts and beliefs, and because of that, they’re okay with posting doctored images if the message represents something they agree with.

Fixing This Problem Means Thinking Like a Teen

This past year has confirmed what I had been worried about for some time, namely that classroom lessons teaching source analysis—and even lessons specifically designed to teach media literacy—are failing young people because we aren’t meeting the learner where he/she is. After all, how effective is a lesson analyzing the values and limitations of Stalin's use of photo manipulation during the Great Purge if we don't connect it to the modern usage of technology to post memes and doctored images? More importantly, how long will students continue to see social media this way? Will we as educators finally adapt to Gen Z just as they come of age and change how they communicate?Once more, I have more questions than answers. As is often the problem in education, teachers are faced with too many problems without the resources to fix them. But I fear far too many teachers are approaching this problem from the wrong perspective: their own. The result will surely accelerate the spread of misinformation and half-truths, and more people questioning what they see on the news.

My Senior Year of College Was Ended by COVID-19

Sitting in my apartment scattered with books, laundry and empty coffee mugs, I get ready for my first Zoom class. I send out Zoom links for afternoon interviews for my campus newspaper job. Through the wall, I hear my roommate's muffled voice while she talks to her class. Our cat wanders back and forth between our rooms, getting familiar with our constant presence. Later in the day, I plan to sit in the yard of a friend’s house to catch up on classes while she sits on her steps, properly socially distanced. This is the new college experience.College exists because it is supposed to prepare us to find jobs in order to comfortably support ourselves. But what are students supposed to do when that plan’s derailed by a pandemic?I entered my senior year in college with a mixture of excitement and fear. I was planning to leave my safety bubble and enter the workforce. As a creative writing major with a minor in journalism, I knew that the job market would be hard to break into, but I love writing stories, so for me, the post-grad challenge seemed worth it.Then COVID-19 hit.

My friends and I waved farewell from six feet apart.

Online Classes Are Nothing Like the Real Thing

Washington, where I attended college, was the first state in the U.S. with a confirmed case. When the news got out people immediately began stockpiling groceries, taking shelter and working from home. I was isolated from my family in Montana: They were still unaware of what kind of impact COVID-19 would have on their lives. I tried to warn them, in between assurances that I was safe and school was still in session—albeit online.I completely understand why classes had to be moved to the internet, but that doesn’t mean I’m not disappointed or frustrated. Even though my professors were trying their best to give us the education I paid for, classes undeniably went down in quality. Students who paid thousands of dollars for in-person instruction were now paying practically the same price for a pass-fail education. Since many students moved home, some out-of-state students were paying to take classes in their childhood bedrooms.Then news came that graduation would be virtual, too. Instead of seeing me walk, my family got to see my name pop up on a screen in their living room, states away. I didn't get to say goodbye in person to my professors, peers or the university, itself. My friends and I waved farewell from six feet apart.

Five weeks before graduation, my family lost a member to COVID-19.

And Now: The New Reality

Balancing finishing school, a writer/editor position and a post-graduation job hunt is challenging, especially in isolation and the in midst of a pandemic. Motivation and drive are hard to sustain when outside stressors, anxieties and hardships are banging on the door. I’ve been reporting on what’s been happening locally while trying to balance my own life, all while people close to me have been losing their jobs and moving home, leaving piles of furniture outside their apartments. The post-grad job hunt’s been put on the back burner, but not forgotten. I still have bills to pay.I felt selfish for my worries about virtual graduation and struggling to find jobs because people were falling victim to the virus—people I knew. Five weeks before graduation, my family lost a member to COVID-19. I attended my relative's funeral sitting at the same desk, scattered with the same to-do lists and notes where I’d been attending class. My family and I couldn’t mourn together or hug. Instead, we sat in our assigned virtual boxes and stared at a screen, muting our tears.I didn’t expect that the hardest part of college would be missing the chance to say goodbye to those I love, while also saying goodbye to life before COVID-19. However, I’m still in a position of ample privilege, and it’s important for me to recognize that. I have the support of my family and professors. I have a job through the university that I was able to keep. I’m also using what I’ve learned in school to create platforms for people to share their stories during this historic time.Now it’s on the class of 2020 to fix this. With an upcoming election on a collision course with a potential recession, it is our job to make our voices heard and fight for those suffering. And it’s the job of those with power to hear us. Students pay their life savings and take on massive debt because we’re conditioned to believe there will be jobs once we’re done with school. That’s not a given anymore—if it ever was.We’re leaping into the unknown, but we’re not alone. There are thousands of students right now working towards an education in order to find solutions to these problems. Listen to us, and help us achieve our goals before and after graduation. We need you—but even more importantly, you need us.

How to Debate Flat Earth Believers

After nearly a year of revelling in flat Earth articles, podcasts, and memes, I finally have my chance to talk to some “flatties” in the wild. The room is bunker-like; small, slightly tatty and buried beneath a London Premier Inn. There’s about fifteen people total, ready to roll.It is about to be a very frustrating experience.

Why Do People Think the Earth Is Flat?

A growing number of people think the earth is flat. My curiosity was pricked by an article in The Economist. Since then, I’ve debated (or, more accurately, “debated”) many flat Earth believers. Here, I offer up some words of advice on how to steer a flat earth debate.There’s only one other “globetard” in the room: An elderly woman who stays quiet throughout, except once to ask a question about where the edge of the earth is. I like her. During the questions, when she senses my annoyance, she’ll knowingly wink at me in solidarity. She’ll eventually walk out in apparent disgust. The debate itself is a mess. I never finish my fifteen-minute presentation. Constant interruptions are raised against points I’ve never made. No one takes the time to realize I’m fully acquainted with flat Earth literature. I try to advance a more sophisticated argument they’ve never considered before. Half the room never stops to listen to it. The other half never gets the chance to, what with the constant bickering.

The Flat Earth Discord in Society

Steer one: You are not going to change the mind of a convinced flat Earth believer. They’re irredeemably trapped by the assumptions they’ve made about the nature of the world. One famous flat Earther says flat Earthers have a 99 percent retention rate: Once you go flat, you don’t go back! I doubt serious statistical methods were deployed to arrive at that figure, but I’ve little doubt that the truth’s not far off. But this retention rate is only evidence of what it takes to be a flat Earther in the first place. If you are already prone to misunderstand the world to the extent required to believe the earth is flat, you won’t have the conceptual tools to ever realize your mistake. No wonder you never change your mind.Given this, you should question whether it’s worth debating them. For any debate (whether it’s politics, religion or what to see at the cinema), you must ask, “Why bother?” Is it that the participants don’t know the truth and are trying to find it out? Are you hoping to convince the other side? Are you open to being convinced by them? Or are you just hoping to show how intelligent and bright and educated you are (i.e., show how big of a dick you can be)? Ask yourself why you’re bothering to debate given that the other side is never going to change their mind.There’s a fiercely religious old lady: every word of the Bible is true; Lucifer is behind it all; Jesuits assassinate people. I never get a chance to tell her that her belief system has the merit of consistency. I’m no psychologist, but another is clearly on the autistic spectrum. It’s impossible to think this isn’t connected to their being flat Earthers. Somebody brought their daughter—I guess she must be fifteen or sixteen. I’m impressed as she fires pointed, direct questions at myself and the other speaker. Puns aside, she’s clearly on the ball.Never think for a second that these people are stupid or crazy.

Can You Prove the Earth is Round?

Steer two: You’ve probably overestimated your ability to prove the earth is round. Unless you’re unusual, your knowledge about the earth’s shape is testimonial. Lots of knowledge is testimonial: chemotherapy cures cancer; there are humans in Gambia; your taxi is outside. Unless you’ve recovered from cancer, been to Gambia and, until you step outside to get the taxi, this is all testimonial knowledge taken from some source (such as a doctor, or Wikipedia or the Uber app on your phone).Most people seem to ignore this fact. In debates, “globies” too often conflate their conviction that the earth is round with their being able to prove it. And then they quickly run aground when they try to prove it. Delivering an incontrovertible proof of the earth being round is hard! And when you fail, this will consolidate the flat Earther’s stance—they’ll dig their heels in all the more.

Never think for a second that these people are stupid or crazy.

Testimonials Are a Valid Form of Evidence

Steer three: Testimonial knowledge is just fine. Flat Earthers will often demand that you prove the earth is round. When you fail, they claim victory. But that’s an odd thing to do! Imagine someone in the pub told you chemotherapy wasn’t good for curing cancer. How weird it’d be for them to start demanding that you explain the ins-and-outs of pharmacotherapy, medical oncology and biology and—when you failed to do so—that they’re right that chemotherapy is pointless. You’d be well within your rights to shrug your shoulders and tell them that, just because you didn’t know the exact specifics, what of it?“If the earth’s round, what explains why everyone in this room has got it so wrong?” I’m asked. It’s not because you’re mad, I say. It’s not because you’re stupid, I say. It’s not because you’re irrational, I say. I suspect you have a problem with testimonies from authority figures; you deny it, because you were simply told to believe it. I can’t imagine him denying what I’ve said. Surely we both agree that he distrusts authority sources? But he’s skeptical of authority figures and I guess he thinks I’m one of those. So he says I’m wrong. I don’t think he really heard what I said. He saw the mouth move but ignored the words.If you really must ignore the last steer and get into a protracted debate, I still have advice.

Don’t Expect Flat Earthers to Trust Your Research

Steer four: Flat Earthers don’t trust your sources. Photos of the earth are made with Photoshop. Videos of the curve of the horizon are the product of a fisheye lens. (Warning! Most photos of the globe are composite images patched together by a computer, and most videos showing the curve showing the curve are the product of a fisheye lens!) But they have their own authorities. They have pictures alleging views of faraway objects that’d be impossible if the world were round. They have (tedious, hour-long) videos of laser experiments allegedly showing there’s no curve.What’s sauce for the round, lump goose is sauce for the flattened gander. You both must play by the same rules. If you can’t rely on your testimonial sources, they can’t have theirs either. For each meme and video, shrug your shoulders—you’ve not witnessed these things. Just as they say we must ignore the live feed from the ISS station, we get to ignore their photos and videos. Denied access to their sources, it’ll be effectively impossible to “prove” the earth is flat.(And having made this point once, don’t let up; all too often, we let people in debates “forget” awkward facts and move on. On this matter, though, you must give no quarter; deny them their sources—it’s only fair.)Witches weigh the same as ducks. That’s what Sir Bedevere proves in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Listening to the flat Earthers makes me think of him. It’s all eerily similar.Consider some flat Earth arguments. Space must be fake, they say, because rockets wouldn’t work in space as there is nothing for them to “push off of.” It’s absurd, they say, that we’re hurtling through the galaxy at 230 kilometers a second—surely we’d feel it, like we were on a galactic roller coaster? Things which are far away don’t disappear from the “bottom up” because of the curve of the earth, but because of some (usually garbled) claims about vanishing points, perspective and the resolution of our eyes.It’s all nonsense, of course. The conservation of momentum explains how rockets move. And forces don’t act on us at high velocities, but only when our velocity alters (which is why you don’t feel any g-force whilst driving on the motorway at 60mph—but feel a lot of g-force on a roller coaster at the same speed). And, yes, the curve of the earth is what explains why things (say, the sun) disappear bottom up as they go over the horizon.I wouldn’t bother explaining any of this.

A growing number of people think the earth is flat.

Use Flat Earth Arguments to Your Advantage