The Doe’s Latest Stories

America’s Reproductive Future Is Reminiscent of Romania’s Past

I feel the little white pill settle into my stomach, praying that it works. When I go back to bed, I think up a plan in case the pill fails and I become pregnant. A few weeks later, tears of joy fall down my face when my period comes. I don’t tell anyone what happened. This memory has haunted me for years, feeling both guilty and relieved, marveling at the choices my mother could have had and what she might think. Would she be disappointed in me? Would she even care? Would she be jealous that I could run to CVS, buy a $50 pill and a Coke and call it a day?For decades, women in Romania were terrorized by the government. Stripped of their rights, women’s bodies were used as incubators to increase the population and build a robust military and workforce. The monstrosity of Romania's past discretions is distinctly poignant as we watch American women hold on to their reproductive rights by a thread. As an American woman, I may face the same fate as my biological mother in Bucharest—the same fate that led me here. In reading this, you are engaging with the consequence of Romania’s abortion and contraception ban. I was a Romanian orphan.

The end of Roe v. Wade could flood the foster system and force unbearable weight on the children within it.

I Am a Direct Result of the Romanian Abortion Ban

If you look roughly 60 years into Romania’s past, you’ll come across Decree 770. In the 1960s, Communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu restricted abortions and contraception to boost birth rates and create a larger Romanian population. In addition, divorce was made nearly impossible and legal separation was only allowed under exceptional circumstances. These constraints, of course, came to the detriment of women—and their children.The termination of women’s rights led to a severe overpopulation in Romanian orphanages, making the conditions sickly and dangerous. Children were sometimes left to die due to a lack of proper care. Those who did survive often suffered from physical and mental illnesses. For many Romanian parents, sending a child to an orphanage was meant to be a temporary placement until the family could afford to come back for them—most of these children were never meant to be orphans. Being in that orphanage meant my mother might have planned to return for me one day.In the ’90s, after Decree 770 had been lifted, 20/20 released a special about the conditions of Romania’s orphanages—the horror behind the stone walls. Americans reacted with shock and grief, and thousands flocked there to adopt. Known as Romania’s “lost generation,” many orphaned children, me included, were released to new American parents and sent to assimilate to a disparate way of life.But this mass exodus caused issues for the Romanian embassy; simply put, too many Romanian citizens were leaving at once, causing stress to the record system and causing issues for adoptive parents who, like my own, were trying to return to the States. This forced the government to pause international adoptions.

We Need to Give More Attention to Foster Children in the U.S.

In the United States, the foster system is collapsing in on itself. In my state, Michigan, the local news plays what are essentially commercials of children advertising themselves and why they deserve to have a loving family. As we all know, though, the older a child gets, the harder it is to get out of the system. And within the system, abuse and neglect are rampant.As Americans battle over what constitutes “life” in the physical and spiritual sense, living and breathing children are at the mercy of incompetent institutions that provide nothing for their well-being beyond the bare-bones basics. In return for barely taking care of the children in the foster system, leaders expect praise and support. Meanwhile, it’s evident to anyone paying attention that the government has no plans to support these children in ways that matter.Lately, there has been a narrative that no one is entitled to have children and that adoption shouldn’t be used as family planning, which can be a tough pill to swallow, but it’s true. Adoption can be a traumatizing event—for the child, the biological parents and the adoptive parents. I can recall my parents’ stories about having guns to their heads at the embassy and not knowing if they would be able to leave the country.Adoption should not be viewed as the last resort for those who want to have children. It is not the fail-safe; it is not the worst-case scenario. Many international adoptees are forced to assimilate into the culture of their adopted families without ever having the chance to experience their own. Like Romania, U.S. domestic adoption has become a point of commerce rather than an opportunity to create a loving family. The end of Roe v. Wade could flood the foster system and force unbearable weight on the children within it.

I’m facing the same hell in my 20s that my biological mother lived in hers.

Romania Serves as an Example of What Can Happen if the U.S. Bans Abortions

The American government gave women the right to choose with Roe v. Wade. Still, there has always been a sense of contention surrounding this ruling, with so many believing that women should be carrying their pregnancies to term, no matter what. But we are now closer than ever to losing the right to abortions and birth control, with some states already living in that circle of hell.As the world crumbles, solutions and programs are required for stability. America is planting its feet firmly on the ground and threatening to take away our options. Being forced to carry a baby and giving birth to one can be equally as traumatic, especially when the standard for prenatal care can vary so greatly. Black women, for example, are 3.5 times more likely to die in childbirth than white women due to inequality in the delivery room. When there are no programs or standards in place for care before, during and after birth, peoples’ limits are stretched and infrastructure fails.With the cost of living steadily rising and another recession on the horizon, it’s no wonder the political right is panicking over a steadily declining birth rate. No one wants to have a child in a country where they are not supported, and it’s difficult to envision a future in America different from Romania’s past, just 30 years ago.Governments will seemingly do all that they can to strengthen the military and workforce, and our rights are currently in the way. At this point, I don’t know if staying in Romania would have been different than coming to the U.S. I’m facing the same hell in my 20s that my biological mother lived in hers.

As a Journalist, I’ve Been Trolled Online: This Is Why It Needs to Stop

Journalists are known for being thick-skinned, taking no nonsense and being fearless in the face of everything they report on—after all, it comes as part and parcel with the job description, so it must be true, right? But there are different types of journalists and writers within the realm of the media, and not all of us are completely fearless and as thick-skinned as one might initially imagine. So what happens when a journalist, thick-skinned or thin, is named, shamed and called out for simply doing their job? Staff writers who work at various international news outlets and publications know all too well what I and many others have been through and continue to go through. And as an entertainment reporter like myself, who reports on high-profile celebrities, there is a risk that you might write something that they don’t like.

I felt shaken to my core.

Getting Trolled Online Made Me Question My Career Choice

I wrote an article not too long ago about a well-known celebrity that later left me questioning my career and wondering if I was the ethical journalist I pride myself on being. The article was assigned to me and was based on some tweets that the celebrity had published on Twitter. Fair and balanced, I wrote the piece and ensured it adhered to everything it needed to. The piece then went through legal—a process where the article gets read by a solicitor, who will then recommend any changes to make, ensuring it’s legally sound and won’t get the publication into hot water. After about half an hour, my editor informed me all was OK, and the piece was published. Shortly after, I was hit with a barrage of hate messages telling me what a bad journalist I was. This was the first time anything like this had happened to me, and I felt shaken to my core. I then realized that the celebrity had named and shamed me online: This was when I knew that I wasn’t as thick-skinned as I had first thought I was. Tears trickled down my face, and an overwhelming feeling of sadness washed over me because I had been called out, hit with hate and left in the gutter for simply doing my job. Devastated that I might have done something wrong and feeling as though I should pack in the career I had worked for so long to forge out for myself, I couldn’t fathom how hopeless I felt from one single action. Luckily, my team backed me all the way, and after blocking the necessary accounts, everything blew over and all was OK in the end—but that didn’t and still doesn’t stop my nerves from creeping up on me whenever I have to write about that celebrity again.The thing is, it seems that celebrities don’t realize that we’re only doing our job and that behind the byline, we’re real people too. Recently, I've seen more and more colleagues of mine get “dragged” and trolled online by celebrities and their online fans because they didn’t like an article that was written about them. It seems that these people have completely forgotten that just like them, we have feelings too.

Staff writers and journalists have feelings and emotions too.

Journalists Are Just Doing Their Jobs

Recently, I saw that a journalist I know and work with was hit with blistering criticism after they wrote a piece about another high-profile celebrity and TV star. They were doing their job and simply writing something that they had been told to—their photo and name were plastered across the internet and a hate campaign was launched against them. Knowing exactly what they were going through, I could sympathize with the emotions they were feeling because I had been there. And I often see other journalists and writers I know being targeted with hate online by the celebrities they write about simply because of articles they have been asked to write. Being a journalist or staff writer at an online publication means you’re writing newsworthy pieces in order to attract traffic to the publication’s website and, more often than not, writing what you’re told. Staff writers also don’t necessarily pick their own headlines, either, which will no doubt surprise many. If the journalist knows the publication well, their headline might stay, but headlines can also get tweaked to improve clickability—meaning it might not be worded how writers had imagined, which sometimes happens. We are given a list of articles that need to be written, often based on other articles online, tweets, Instagram posts or magazine clips—and then we have to write them up, adhering to relevant media law and publishing guidelines, as well as the publication’s house style. There are some quite rigorous laws and guidelines to follow as a journalist, and not doing so can have big repercussions for yourself or the publication you write for. Obviously, everything is written because it’s in the public’s interest, and this is what keeps websites and newspapers ticking over. But most of everything staff journalists write is written because it will do well for the website, driving traffic and readers and, in turn, keeping them employed. Celebrities need to understand that if they’re putting themselves in the spotlight, releasing books, press releases, appearing on TV shows and using social media platforms to air their views, then they’re likely going to be written about because after all, that is the job of a journalist. Staff writers and journalists have feelings and emotions, too, and we don't always choose our own headlines or pick out the stories we want to write. I have become accustomed to trolling a little more now and think my skin has thickened over time, which doesn’t make me as mad as I had imagined it would. In fact, it’s probably improved the way I do my job and given me more of a voice to speak my mind—but that doesn’t mean it’s OK for people to troll us. We have a job to do and we do it—and dealing with trolls shouldn't be part of the job description.

Posting on Reddit’s Gone Wild Led to Me Having an Internet Affair With a Stranger

“I post to Gone Wild, like, once a year when I need a confidence boost,” my friend said in a recent conversation. “What is that?” I asked. She explained that r/GoneWild is a subreddit where Redditors share naked photos of themselves for other users to upvote. With over 3 million members, the community is one of the most active on Reddit and one of the sexiest places on the internet. The page is also surprisingly supportive and kind. It's rare to see rude or negative comments posted underneath photos, and all body types are appreciated. I was intrigued by our conversation and decided to post to Gone Wild. I’ve always liked taking nude photos of myself and sending them to partners or random crushes. There is something nice about looking at my body in a photo and enjoying what I see. It reminds me that a sexual being lurks underneath the baggy sweatpants.

Posting a nude photo of yourself to a 3,000,000-plus member community is quite thrilling.

I Started Sexting a Stranger Who Commented on My Nudes

After creating a Reddit account where I could post NSFW content, I soon found myself alone in my room in front of a full-length IKEA mirror. It’s not easy to hold a phone while photographing your body from an attractive angle. I made sure my face, photos and other personal items that someone could use to identify me were not visible on the screen and started snapping away. Now there was just the question of what photo to post first. I chose a likable nude and hit “Create Post,” feeling a rush of adrenaline. Posting a nude photo of yourself to a 3,000,000-plus member community is quite thrilling. I did not know what to expect, but I was ready to be surprised. Almost immediately, my phone started buzzing with notifications from private messages, post comments and new followers. I had never felt more popular. Most of the messages were frightening dick pics or long-winded introductions from Star Wars fanatics. It was fun to read through all of them. One message stood out. It was from a user complimenting my tattoo. I replied. My inbox buzzed immediately with his response, and soon, we were in an electric conversation about tattoos and his ruined boxer briefs. Talking to my sexy new pen pal was fun and made me feel more wanted than I had in a long time. Soon, we were messaging every day and exchanging nudes. When his name appeared on my phone screen, I immediately felt turned on. It was like a Pavlovian response. One time, I was in the middle of cooking dinner with my roommates when my phone buzzed on the counter. I immediately became distracted and stopped listening to the discussion about growing herbs. “Basil, thyme, dill…what else?” one of the roommates asked. Instead of answering, I read the words “miss youuu” on the screen. “Miss you too,” I said out loud. “What?” my roommate replied. “Oh, sorry. I meant mint,” I said, confused. Then, I slipped out of the kitchen and up to my room, phone in hand. Between the sexting, we filled in small details about our lives. He was older and working from home in a nine-to-five job, feeling trapped during COVID. I was at a particularly chaotic time in my life. I had just finished university far away from home and was unsure where I wanted life to take me next. Perhaps my life sounded exciting and novel to him, while his stability and routine attracted me. While we lived on opposite sides of the world, we often imagined how it would be to meet in person. We talked about what snacks he would have waiting at home when I arrived and what bars I would take him to while playing tour guide in my city. After about a week of talking, he asked, “Would you ever show me you? Like, if I did too.” We had seen just about every part of each other's bodies except for the face. While in theory I know never to share my face with an internet stranger, I felt safe enough to send a photo of myself. His face was surprisingly attractive and confirmed hot people are hanging around Reddit. I saved it to my camera roll and looked at it an embarrassing amount.

Maybe you can only sext so much before the phrases start to feel stale and the ass pictures become repetitive.

I Didn’t Know the Person I Was Texting Was Married

Our intense messaging continued for about a month before he shared a surprising piece of information. After I sent a photo of myself one night, he replied, “There’s no way you could be single, right?”“Mm, it’s complicated,” I typed. I had been dating a good and kind person for several months. While I liked their company, I was in the process of getting to know them and figuring out what type of connection we had. We were in more of an exploring phase than a committed one. “Are you single?”“I knew it!” he wrote. “And same, it’s very complicated. You might hate me forever.” My heart immediately started pounding. I gripped my phone tightly, waiting for it to buzz with his next message. A minute later, I received a photo of his hand. On one of the fingers was a sleek black wedding ring. He explained that he had been together with his wife for a while, but the passion had faded. He described it as a dead bedroom situation. At first, I didn’t reply. There are certain things one knows to be wrong or right, and sexting with a married man is generally considered wrong. Was this something I wanted to be involved with, however indirectly? Eventually, I wrote him back “good night” and fell asleep. When he messaged me the next day, I replied. I liked talking to him too much to make the “right” decision. “I thought you hated me,” he wrote. “Would you be sad if I hated you?” “Absolutely.” He apologized for not giving me the whole story in the beginning and said he got caught up in the joy of feeling wanted again. A part of me did feel bad that he was sending sneaky messages while eating lunch with his wife. However, it didn’t stop me from continuing the internet affair. We chatted for about another month or so, but the messages lacked the same electricity. Gradually, our responses slowed, and the conversation died. I started to prioritize the life around me instead of our digital conversation. Perhaps reality replaced fantasy. Or maybe you can only sext so much before the phrases start to feel stale and the ass pictures become repetitive.

Our Brief Encounter Taught Me About What I Want Out of a Relationship

Looking back, what bothers me most about our interaction is that he said his situation (being married) was about the same as my situation (dating someone). I don’t think being married is the same as casually dating around. Marriage is a big commitment one should handle with honesty and care. I hope his partner would understand and be OK with him sexting strangers on Reddit as a way to fill his needs. In the end, this experience made me think about what I want (and don’t want) in my own romantic partnerships. If I choose to get married in the future, I would like to be comfortable communicating with my partner when I feel unsatisfied with our sex life. I hope we will be able to find solutions together, even if that means opening up the relationship at some point. In the meantime, I might post on Gone Wild again.

The Scars of The Troubles Live on Through Two Generations of My Family

Thanks to the release of the Oscar-winning film Belfast, people have started to turn their attention to Northern Ireland and gained insight into the national trauma that was The Troubles. For two generations of my ancestry, The Troubles was a very real and personal trauma, and the scars of that conflict remain to this day.The film, which was awarded Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards in March, is an autobiographical look into filmmaker Kenneth Branagh’s working-class Belfast family life during the advent of The Troubles. It tells the story of the historical conflict through the eyes of a young boy, was described by Branagh as a search for “hope and joy in the face of violence and loss.” From the 1960s until the peace agreement in 1998, my parents and grandparents’ lives were shaped similarly by the political conflict, which pitted Catholics against Protestants and led to never-before-seen bloodshed in the region. In total, The Troubles resulted in around 3,500 deaths and some 50,000 injuries. While Catholic nationalists fought for an independent Ireland liberated from British rule, Protestant unionists defiantly sought to demonstrate their allegiance to the U.K.

A generation later, my parents lived under the same reign of terror.

As a Police Officer, My Grandfather Experienced Violence from the IRA

My grandfather served as a Royal Ulster Constabulary police officer over the course of The Troubles. It was arguably one of the most dangerous positions to be in during that time, as some 319 RUC officers were murdered and 9,000 injured by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). By 1983, Northern Ireland was the world’s most dangerous place to serve as a police officer, twice the rate of even the second-most dangerous country, El Salvador. All of which resulted in my grandfather witnessing his fellow colleagues getting gunned down by the enemy, and himself descending into depression and alcoholism as he contemplated his own mortality every single day.At the very start of his career in the late 1960s, my grandfather experienced such violence firsthand, as his police station was ambushed by the IRA one night while he served on duty. He was shot six times during the surprise raid, and barely escaped with his life. After being rushed to hospital, he met my grandmother who was working there as a nurse at the time. And the rest, as they say, is history.But in spite of all of that, on his 90th birthday, my grandfather sat in his armchair and reflected on his life. “I hold no hate in my heart for what they did to me in 1968,” he said. A generation later, my parents lived under the same reign of terror.The two religious groups were so divided that my then eight-year-old mother passed Friesian cows in a field one day and asked her mother whether they were Protestant or Catholic. They must have belonged to one of the two sides, she thought, because everyone else did. Such a naive perspective is something which Belfast achieves with both heart-breaking and eye-opening effect. In the film, nine-year-old protagonist Buddy has difficulty understanding the conflict, and relies on his parents to educate him about the turmoil going on around him. Such exchanges are endearing, but successfully illustrate the senselessness of the violence which has destroyed this young boy’s home.

My Parents Have Traumatic Memories of Street Bombs in Belfast

As my mother matured, so too did her understanding of the conflict and the atmosphere in which she lived. She recalls, at 17, sitting in her car in her driveway and praying that she would be spared as she turned on the ignition. It was an all-too-real fear that a bomb would have been planted under the car to kill her police-officer father. In her younger years, she had grown completely accustomed to walking past army trucks on her way to school and being searched before walking into Sunday school or the supermarket.On the other side of the city, my father also experienced the trauma of The Troubles. Very rarely would he speak about what he witnessed, but when he did, it was clear the memories of the conflict had stayed with him long after the conflict ended. While working in central Belfast, he witnessed a car explosion one Tuesday morning on his way to the office. An RUC officer and his girlfriend had been targeted, and my 28-year-old father saw the couple catapulted through the roof of their vehicle as the bomb detonated without warning. My father rushed over to assist the pair before emergency services tended to the scene. He only started to believe what had happened when he saw the incident being reported on the 10 p.m. news later that day. Only weeks later, my dad had also stopped a young family from walking down a city center street after spotting a suspicious-looking vehicle, which was parked in front of a government building. Moments later the car exploded, and thankfully no one was hurt, thanks to his instincts.

She recalls, at 17, sitting in her car in her driveway and praying that she would be spared as she turned on the ignition.

I’m Deeply Connected to Ireland and its History of Violence

For my parents and grandparents, this reign of terror was just a fact of life. But having grown up in suburban London some years after the peace agreement, I found it hard to imagine these were my ancestors’ experiences when I was told the stories of The Troubles.Now older and more understanding of the context, I am grateful for films like Belfast, which have presented similar stories to my parents’ and grandparents’, while conveying the importance of peace in Northern Ireland today. Having visited the region countless times over my life and knowing my family’s history, I feel deeply connected to the region and care deeply about its future.But over the past several years since the European Union Referendum, I believe William Faulkner’s infamous words, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” have never been truer for Northern Ireland. Just over two decades since the peace agreement, it’s no wonder that the trauma remains just below the surface, for my own family and the rest of the country.

Is There a Place in Pop Culture Journalism for a 40-Year-Old Woman?

Over my 12 years as an entertainment reporter, I’ve published thousands of stories, from news pieces to 10,000 word features. I’ve sat down with everyone from superfans to George Clooney and Julia Roberts, and I’ve written about so many movies and TV shows that I can’t even remember a third of them. I’ve also been called an idiot for thinking an OK movie was just OK, been tagged frequently on Twitter by people who just want to let me know my opinion is wrong and—almost a decade after I first published the piece—still hear from fans of a comedian who think I gave him an unfair shake during an interview. I’ve never been doxxed, but I’ve lived almost every day of my editorial career with that looming threat. And all because I’m a woman who has dared to express her opinion on pop culture.I got into entertainment media in part because I just really loved to watch TV. A child of the ’80s, I grew up with basically unlimited access to whatever was on the tube at that time, from Three’s Company to MTV Spring Break. I developed a thirst for content, be it movies, TV, books or magazines, and went to college to study journalism like my parents. I wanted to write for Spin or Entertainment Weekly, two publications I’d always been thrilled to see come in the mail. My professors didn’t really know how to get me there, though, and I left college a little disillusioned with the industry. Instead, I took my college radio hobby and turned it into a career in the music business. Fast-forward a couple of years and boom, I met some cool people through music that worked at an entertainment website and thought I could do what they did. They invited me to come work for them, and I was thrilled. I remember that I told them it was my dream job to get paid to write about things I already loved. “Ha,” they laughed. “We wouldn’t go that far.” Still, then, over a decade ago, I really thought it was true.

Looking at the entertainment journalism market even now, I think I somehow fucked up.

Pop Culture Media Has Gone From Bad to Worse

The longer I’ve been in the business, the worse it’s become. Since we’ve moved into the “pivot to video” era of digital media, I’ve also faced frequent unsolicited comments about my appearance, my weight and my vocal affect. I was called a “rhino” in the comments on one video years ago and have thought about it every day since. “Who cares?” my co-workers said. “They’re trolls!” But they were all average-looking white guys and never got those kinds of comments, so how much did they really know? I’ve also faced inequality and uncertainty in my newsrooms, where I’ve frequently been surrounded by men with an outright disdain for anything they don’t consider “serious cinema,” i.e., anything that’s not made by men and with the male gaze in mind. I’ve second-guessed every pitch I’ve made, every opinion I’ve had and every base of knowledge I’ve grown. “I clearly don’t know about the right things,” I’ve thought. “How stupid of me.”While a lot has changed in the media industry in the past decade, with many newsrooms becoming more diverse and shining a light on a wider spectrum of stories, entertainment media has managed to both expand and contract at the same time. While creators are diversifying their casting and stories, publishers are also realizing that the stories that drive clicks are the ones about the movies and shows that bring in big numbers, and increasingly, those projects are centered around just a few franchises. Looking for a new full-time gig, I’ve come across more than one senior-level job listing that read like this one I saw recently: “You will be an expert in the field who knows your MCU from your DCEU, your James Bond from your Jack Reacher and your Jedi from your Jawa.” That wasn’t for a gig at a niche comic-centric publication, either—it was for a fairly wide-read and well-respected entertainment site. But as I read it, I just thought what it was really saying was, “Women of a certain age need not apply.”

Women Are Superfans Too—Just for Different Stuff

Looking at the entertainment journalism market even now, I think I somehow fucked up. My interests are wrong. By liking what I liked, and not making a choice 35 years ago to get into a more Comic-Con-friendly sphere, I have made myself the enemy of clicks. I’ve become obsolete because, as the market and our publishers have told us, who really cares about what people like you like? I like a good superhero movie as much as the next person, I really do. I’ve seen them all, and, like any good critic, I have my thoughts about them. But I didn’t grow up enmeshed in the comics. I lived on basic cable, not premium. You can ask me anything about MTV in the ’80s and ’90s, but I’ve never seen a Christopher Reeve Superman movie. My parents didn’t really watch movies and we never went as a family, so what I got into—whether it was Sweet Valley High or Jane magazine—I had to discover organically. I followed the paths that I encountered fervently, but for whatever reason, they just never led me toward superheroes and graphic novels.As a 40-year-old woman, I certainly grew up knowing kids who were into Star Wars, including my brother, but couldn’t tell you a single girl who I went to school with who may have done Leia cosplay on the weekends. That’s not to say that there weren’t girls who were Superman diehards who’ve grown into women who know the difference between X-wings and TIE Fighters. (There are, and I know a few.) But that’s not me. Instead, I have an encyclopedic knowledge of romantic comedies, pulpy tween novels of the ’80s and ’90s, and ’60s sitcoms. It’s always such a surprise to me when publishers or male coworkers are shocked by the success of projects like Bridgerton, Outlander or 50 Shades Of Grey. Yes, they’re all sexy, and people like good steamy action, but also they’re all indications that the market supports and craves content created in part by and directed at women. And moreover, the market craves smart criticism, creative features and broad coverage about and around those shows. Entertainment sites should be looking for writers just as versed in that world, not just writers with thoughts on Marvel’s fourth phase or who was the best Batman. (Christian Bale, duh.)Speaking of comic book movies and other cinematic juggernauts, I believe that, with the size of audiences going to see those movies, perhaps not everyone in the theaters is there just because they really care about plot development or Jack Kirby’s legacy. Tom Holland’s Spider-Man is incredibly popular, and a lot of fans of those movies are young women who were drawn to the work in part because they thought the actor was kind of a dish. There are people who like the romance in the films, the queer subtexts, the gender politics and the increasingly diverse on-screen world just as much as they might like the whizz-bang battle scenes. Let’s write for them just as much as we write for straight-up superfans.

When pop culture journalism narrows its focus and concentrates on content over quality, it’s detrimental to the fabric of cultural discourse.

Making Media More Diverse Is Good for Everyone

I understand that some of my dreams and hopes might be tantamount to shouting at the sea, but it would truly be great if readers also grew to respect and appreciate a diversity of entertainment coverage. Or perhaps the onus should be on publishers, who could take chances on stories their staff felt strongly about and not just ones they knew would be guaranteed click drivers. I’m aware it’s a big ask when so many media companies are run by conglomerates, private equity groups and men focused more on the clickability of content than the actual substance of the work, but that doesn’t mean I can’t dream, pitch and advocate for the level of intelligence and diversity that I believe audiences have. There are times when I think about my career that I truly can’t believe that, in some ways, I feel just as ashamed and uninformed as I did my first year on the job. I curse my interests and my family and think I should have spent more time reading comics anthologies and fantasy novels, despite the fact that I couldn’t have predicted what the media landscape would come. But what I know in my heart—and have always known—is that when pop culture journalism narrows its focus and concentrates on content over quality, it’s detrimental to the fabric of cultural discourse. A more diverse media landscape not only benefits reporters but also serves a larger swath of its readers, many of whom hardly ever feel spoken to or heard, whether it’s by mass-market television, in popular magazines or even in their own lives and families. By giving everyone—reporters and readers alike— a voice and a safe place to find joy, entertainment journalism can only grow.

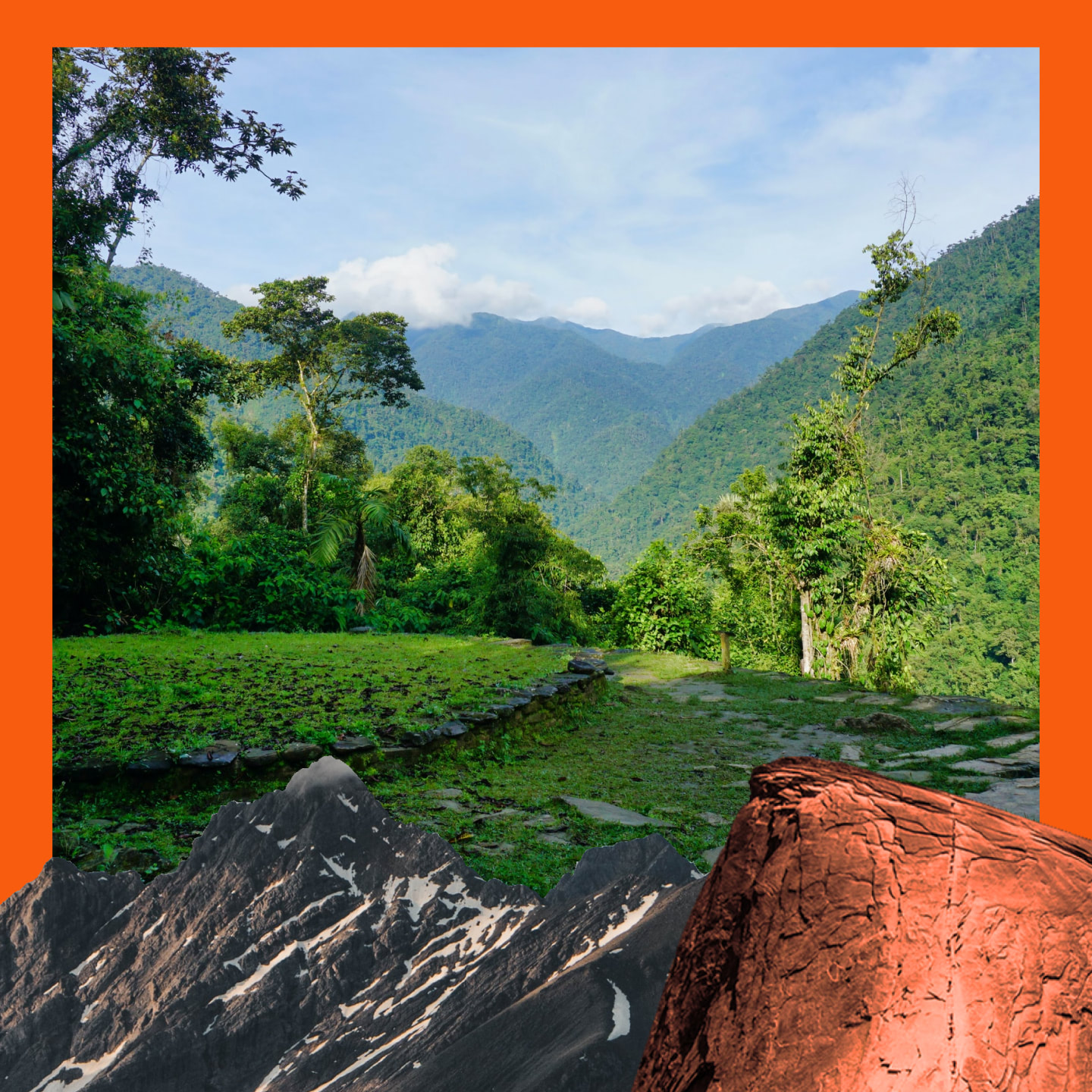

I Rediscovered Myself in the Ruins of a Lost City

All of my life, I had been a couch potato. A bed potato, really. My bed was my best friend and my comfort zone. I’d watch TV, study, eat, read, write and do whatever possible from my very comfortable, very safe bed. Back then, my only exercise was walking to my refrigerator in order to get a snack and then crawling right back under my sheets. It took a while for me to realize that life happens outside of my bed. When I finally did, I threw myself right into the deep end. I started planning a trip that would challenge my physical limitations unlike anything I had ever done before.My journey through Colombia led me to Santa Marta, a city renowned for the natural park of Tayrona, a wildlife sanctuary that is practically heaven on earth. Yet, it wasn’t for this that I had traveled there. It was the Ciudad Perdida, the lost city of Teyuna, an ancient settlement located in the middle of the jungle of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Built some 1,200 years ago, this city is an archaeological remnant of the Tairona people, who inhabited the lands until the Spanish conquest. It had been lost to the world until the 1970s, when some tomb raiders stumbled upon it in search of riches. Pretty soon, I’d be stumbling upon those same ruins myself! That was what I was waiting for, a four-day trek in the middle of nowhere that promised not only the sight of ruins thought to have been long lost but also the rediscovery of something I had long lost within me. I started my journey with a bag that weighed just as much as I did, victualed with all of the food and supplies I’d need on the hike, plus some extra supplies in case of an apocalypse. Vistas and panoramas that belonged on a National Geographic cover had me in ecstasy. Every leaf of every tree seemed to be the most interesting thing I had ever seen. I was surrounded by butterflies of all kinds and colors; woodpeckers, hummingbirds and parrots; flowers of all hues and shapes; exotic fruit and weird plants. Up and down we climbed, crossing over dilapidated bridges and traversing rivers. We trekked along the banks of the Buritaca River, following narrow paths that were shared by the natives and their mules. The scenery only got more unreal as days went by. I felt so profoundly lucky to be able to experience such an adventure.

Every leaf of every tree seemed to be the most interesting thing I had ever seen.

Getting to the Lost City Wasn’t Easy

The long-awaited third day was upon us—the day we’d get to see the Lost City. I couldn’t believe our party were almost there. All battered, bruised and blistered, I had persevered. There was a long way to go, but I felt reinvigorated. My body had already grown accustomed to the trail, my stamina now not so elusive. At the break of dawn, we had already left camp and started on our way to the promised land. The Buritaca River was now waist-deep and as fast-flowing as ever. We had to cross its twists and turns over and over until suddenly, the foliage gave way to an opening that marked the start of the trail into Teyuna. I knew it wasn’t going to be easy. The final trail was only 300 meters long, but they were at an incline as straight as a stud’s back; 1,200 steps to climb, each a slab of slippery, moss-covered rock. As we ascended the trail, the air became thin and cold. Every breath I took felt like it was skinning my lungs raw. My heart was pounding in my chest as sweat dripped down my eyes. “Almost halfway through,” I said to myself on the 500th step. Little did I know how much hard work went into that “almost.” The others were all far ahead, and I was left alone, damning and cursing every single step. There I was, every fiber of my being in pain, my calves now as solid as the same steps I was climbing, mosquitoes feasting on whatever blood I had remaining. But I climbed and climbed and then climbed some more, and finally, I was there.

All Our Hard Work Was Worth It

I had read all about the Lost City’s glory, but as I lay there, I realized no description nor photo could have ever done it justice. It was like something straight out of the film El Dorado. I could breathe in the history and the magic of it all. It was eerily peaceful, pure, a place that felt untainted by the scourge of mankind. All the pain and exhaustion? Gone, extinct, vanished into thin air. The beauty left me in tears. As we sat down at the entrance, the guides told us that the city consisted of a sequence of terraces carved in rocks, connected to each other by tiled paths. Smaller circular plazas, covered in grass and encircled by moss-covered slabs, dotted the city. These, we were told, were what remained of the huts that were previously inhabited by the natives before the city was abandoned. As we roamed about, the group was oddly silent. There was no need for words. It felt as if speaking would take something away from the sanctity of the place. As we walked, our guide recounted the tales that had been buried away for so long. He told us about the Tairona’s traditions, their culture, their customs. So different, yet so similar to ours in principle. Happiness in simplicity—this is what I had been missing. I was too enthralled in things that were now evidently unimportant. I had grown up running around my father’s field back home in Malta, half an acre’s worth of arable land where he used to grow all kinds of stuff; filling our bellies with the plumpest and flavorful veggies and our home with plants and flowers of all sorts. I’d explore and go on all kinds of adventures with my dad. I had forgotten all about this. I was suddenly reminded of my roots, of where I had come from. Somehow, against all odds and logic, I had known that this was where I’d find my answer—that I’d rediscover myself in the depths of the jungle in the middle of Colombia.Finally, we reached the highest point of the site: a ledge overlying the entire city that gave us a vista unlike any other, which words fall short in describing. Surrounded by the lush, verdant mountains of the Sierra Nevada on all sides, we could see a series of five circular terraces, each wider and more elevated than the last, linked together by a tiled trail hewn in all shades of green.

The beauty left me in tears.

Seeing Teyuna Was a Spiritual Experience

But it wasn’t until we were all standing on the largest terrace that it suddenly occurred to me—to all of us, really. A feeling seemed to resonate with us all, in unison and in harmony. “We really are nothing in this world,” I heard myself saying. Standing there, in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by a mountain range we had come to call home after just a couple of days, we felt like we were absolutely nothing. Not in the nihilistic sense that nothing we do matters or leaves an impact; more in the sense that in being nothing, we are also everything. I know it sounds vague, but that’s exactly how we all felt. We were suddenly aware that we are all part of a “great something,” that we as individuals are nothing, but together, we are whole. Nature is a part of that wholeness. I felt alive for the first time in years. I could feel the raw, untapped power of everything that surrounded me. I lay flat on the ground, rolling on the grass, absorbing all of it. Every breeze gave me energy, the sun on my face gave me a warmth unlike no other, the earth underneath felt like an extension of my being. I felt connected. I was in my father’s field once again. I could hear him calling me for the first time since he died. The voice I had missed so much was now so loud in my head, I burst into tears.I had gotten all that I had come for. Now we had to walk all the way back. We’d be passing through the same paths with nothing new to see. We’d be saying goodbye the following day. I had moaned and groaned all the way there, but at that moment, all I could think of was how I’d manage to go back to normal life. But I knew I wouldn’t be returning to the life I had before—I had been reborn.

I Gave Up Eating Meat for a Man

My ex-boyfriend was obsessed with meat. In fact, he was so obsessed with meat that it bordered on pathological. An average evening at our place went something like this: He’d order in vast quantities of hot wings, burgers or fried chicken, then put on a YouTube mukbang as he ate—watching bigger, meatier men shovel down more food than he could manage, in some bizarre cuckolding ritual.My ex felt no shame about his meat consumption. He saw meals without meat as unworthy and would look down on vegans and vegetarians as if they were some sort of absurd alien species put on Earth for his entertainment. I’d laugh at his jokes, but deep down harbored a tremendous amount of guilt from consuming animals and had for some time. I’d watched and cried over Cowspiracy, Seaspiracy and every video essay on factory farming I could find—but found it shamefully difficult to translate their messages into reality, usually managing a few weeks without meat before caving in. It wasn’t his fault, but it didn’t help that my ex was such a fussy eater. It made sense for us to eat the same things, and there were only three or four home-cooked meals he absolutely loved. All of them contained meat.At the same time, we were growing apart, in general. Our five-year-long relationship was bone dry in other areas, and our dietary preferences were indicative of a wider gulf emerging between us—one where neither person respected the other’s interests and passions. In the end, we broke up for non-meat-related reasons, and once he moved out, I stopped cooking with it at home. Eating at restaurants, though, was a different story. I was always aching to delve into anything dense, fried and animal-derived. I needed something major to shift, something to force me to take meat off the back burner and throw it in the trash for good. Then, I met Tristan.

I was enamored by his boundless devotion to the lives of other beings.

I Felt an Instant Connection With Tristan

I matched with Tristan on a dating app last October, the same night I watched The Green Knight at the movie theater. I found this oddly felicitous—Tristan was a vegan chef, animal rights activist and the pseudonym he’d chosen originated from Arthurian legend, the very embodiment of a green knight. We’d spent a few hours texting before I went into the screening—I remember desperately wishing, yearning for the movie and its questionable sex scenes to be over, so I could recommence salivating over his pictures and fantasizing about fucking him instead.A few days later, we met up at a nearby pub. It was exhilarating—within 10 seconds of us locking eyes, I felt chemistry so intense, it incapacitated me. He was utterly gorgeous in person, with beautiful (if unwashed), long hair, tattoos and tired, sad eyes—a delicious blend of every man I’ve ever been obsessed with since I discovered what men were. Our conversation was slightly staggered and difficult, as if we both knew what would unfold and were simply delaying the inevitable for as long as possible before digging in and devouring each other. Still, I tried my best to listen and make small talk. I had to be polite. We spent a substantial chunk of the date discussing the activism he did: protesting for animal rights groups in the city, building shelters for baby animals in the winter, breaking into farms to prevent horses from being euthanized. I was enamored by his boundless devotion to the lives of other beings. It was a welcome change from most of the men I’d dated previously, my ex included—men so fixated on upholding a masculine image that the very acknowledgment of kindness threatened their sensitive palates. I wondered if Tristan’s respect for animals translated into respect for women. I wondered—eyeing him up and down like a snack—if he’d be better in bed.Within two hours, we’d given into our most animalistic instincts, kissing messily and aggressively, to the dismay of nearby onlookers. Not wanting to put on a show, I dragged him out of the pub and across the park to my place, my brand-new leather Doc Martens cruelly lacerating the backs of my feet as I walked. Tristan had made it clear that he wasn’t a militant vegan and that he didn’t care what I consumed or wore—but already, I was feeling the first sprinklings of shame setting in as I tried to conceal my fashion choices. After a lifetime of being trained for male approval, I wanted him to adore me, and I knew, in his mind, there was nothing less sexy than a girl wearing cow carcasses on her feet. Back at mine, we had some of the best sex I’d had in years. Not only did we share many of the same kinks, I found myself feeling so relaxed in his presence that I came multiple times, which doesn’t usually happen. He was passionate, communicative and considerate—a welcome tonic after I’d been force-fed, begrudgingly, on a meager diet of lackluster fucking that had been gradually reduced over the years until there was nothing left. The sex was so good, in fact, that within hours of him leaving the next morning, we’d already debriefed each other about how things went and arranged to meet up again.

Tristan Made Me Curious About the Benefits of a Plant-Based Diet

Quickly, Tristan and I fell into a friends-with-benefits-type situation.We’d see each other weekly and have sex all night, leaving my flatmates eternally sleep-deprived and each other equal parts stuffed and hungry for more. I was completely blown away by his sexual appetite—not only did he taste better than any man I’d ever encountered but he could just go and go for hours without even needing to break. I soon wondered whether these things were related to his diet. I wondered if eating like him would award me the same energy levels, the same almost-scentless soft skin, the same strength and abundance of orgasms. Partly through narcissism but predominantly through shame, I began to eat fully vegan on days that I’d see Tristan. “He won’t want to kiss me if I’ve eaten meat,” I thought—my lips suddenly a vessel for decades of dead flesh, the bodies of animals from before times still resting on my tongue like passengers on some warped Noah’s Ark. This soon extended to dairy too. Tristan had commented, after once being erroneously served a chai latte with cow’s milk, that he felt a thick, mucus-like film develop in his mouth and linger there for the rest of the day. I couldn’t let him taste that on me. I didn’t want to be the milk film girl. It was ironic that I was so afraid of pushing my diet onto a man when I had allowed my own to be dictated by who I was dating my whole life. But as I saw the benefits of a plant-based diet take hold on my own body—as my acne cleared up, my hair grew thicker and my joints stopped aching—it became clear that this decision benefited me as much as it did him. I gradually realized that rather than diluting myself for Tristan, I had been starving myself previously, pushing away what I had always known was best for my body, animals and the planet. I began to reclaim my diet. I stopped eating meat and dairy in any capacity, started watching vegan vlogs and TED Talks on YouTube to educate myself and began collating vegan recipes and cooking them for friends. I relished this time I spent nourishing and replenishing my body and mind. I felt like I knew myself better than I had in years.

I felt like I knew myself better than I had in years.

Being Meat-Free Has Improved My Life

Eventually, I stopped seeing Tristan as often. We still see each other, but our relationship is far more platonic now than it was during our sex marathons. It’s not that what we felt in each other died—though it has certainly been distilled—but rather that our lives began to overflow and swell with other, more pressing activities. He threw himself headfirst into more activism, exercise and a new job at a vegan charity cafe, and I spent time rebuilding my self-esteem and reclaiming my sexuality after my failed relationship and other interpersonal trauma. I now follow a plant-based diet during the week and eat more broadly vegetarian on weekends. Although I’ve not managed to 100 percent eradicate dairy and eggs just yet, I haven’t eaten meat in months, and I plan to never do so again. I’ll forever be grateful for the fire Tristan ignited in me and for allowing me to peel back the layers of myself I had once deemed inaccessible. At first, I felt guilty that all of this had been triggered by a man and not the visible slaughter of innocent animals—but I spoke to other friends and realized how common it is to adapt the diets of those we care about before eventually embracing them as our own. At the end of the day, activism comes in all forms, and sinking your teeth into someone new is seemingly just as effective as disseminating propaganda or rallying for animal rights.In terms of my bedroom activities, I recently had sex with a man who did keto, consuming no carbs and instead supplementing with a substantial amount of meat, and it was as awful as it sounds. Going forward, I think I’ll keep not just meat—but also men who eat it—off the menu as well.

I Often Feel I Have to Choose Between My Gender Identity and Professional Community

It was morning. I lay in bed, waiting for my brain to wake up and checking my social media when a post caught my eye. A group of women in professional attire stood in a conference hall, smiling and laughing. The author of the post discussed the wonderful experience she had with her community at a recent conference. I checked out the organization, and my rush of hope faded. It was a women’s group, promising professional community based around womanhood. The community part sounded great. The womanhood part, not so much. Even before I identified as nonbinary, I balked at the idea of joining a professional group for women. In graduate school, I declined to take part in groups for women in science. After all, I already had community. I had mentorship. My resistance to women’s professional groups made more sense when I realized that my gender identity doesn’t include womanhood. It wasn’t resistance to the idea of a community for women; it was resistance to the assumption that I was a woman. My gender identity includes aspects of both traditional femininity and masculinity but not in a way that instills a sense of womanhood or manhood. I am nonbinary. But gender identity is only one part of me. My love of learning and the value I place on collegial friendships are also part of who I am. For a long time, my job met my needs for learning and professional community.

I’m witnessing the celebration of a culture that is not my own. It is wonderful, but it is not mine.

I Sought Community During a Career Transition

Then came a cross-country move, and geography limited the jobs available in my field. I needed more options. So I tapped into the programs and communities that were available to me as a military spouse. I thought I might find common ground with others seeking career advice and guidance.I felt out of place. On paper, these were groups for military spouses, but in practicality, most members were women. I tried to ignore the pang of frustration whenever someone shared or started a post with, “Hey ladies!” Although there were men in the groups, most photos featured women. They projected an image of polished, professional femininity. I didn’t see myself represented among them with my menswear and short, masculine haircut—I felt pressure to be more polished, more professional to make up for my nontraditional appearance. Conversations about work-life balance were viewed overwhelmingly through the frame of balancing children with a career. I struggled with the implications that motherhood was a valid reason to prioritize work-life balance, while simply wanting more freedom was not. I especially struggled with the occasional comment suggesting that motherhood was obligatory and inescapable for any person who happened to have a uterus.Still, people shared useful resources, and I found programs geared toward providing mentorship. That sounded perfect—I had greatly valued the mentorship I received in academia. Maybe a mentor was just what I needed.Over the following weeks, I had dozens of casual discussions with the mentors in the program. My goal was to understand their career paths and insights. I appreciated the conversations and valued the time of those who spoke with me. Still, I received comments suggesting that some saw my advanced degree as a defect, as evidence I possessed no “real” work experience. The comments added up: an implication that my interest in multiple career fields was a symptom of naivete, a suggestion that I needed extra hand-holding in the job search process, a warning that I should expect to endure extra scrutiny to prove my competence. And, in turn, I felt my mentors’ views on work and professional identity were stifling.Moreover, I expected that resources or groups these mentors might direct me to would be related to profession rather than gender. I didn’t mention my gender identity in these conversations and certainly not that I feel like an imposter in women’s groups; none of that seemed relevant. I did not expect to be shunted toward so many resources, groups and programs for women.

The Mentorship and Community I Found Felt Rigid and Stifling

For several years, I considered transitioning into tech. From the outside, there were career paths that looked stable, portable and intellectually stimulating. Yet, most positions required additional knowledge or at least a substantial reframing of my current skill set. I knew I needed a road map, and this seemed like a great topic to bring up during my networking conversations. However, I didn’t get what I hoped for. One male mentor reacted in utter surprise when I described my interest in tech. I thought a mentor might appreciate my willingness to learn and see what I saw as obvious parallels between my scientific background and technical concepts. Instead, he reacted as though coding was wholly outside my capacity to learn. He and another male mentor tried to redirect me toward customer service jobs instead. I came away feeling demoralized and foolish. Still, I knew these were only two people and their opinions didn’t need to matter to me. But the more I learned about jobs in tech, the more the gender disparity was obvious. I weighed the time and money involved in pursuing a boot camp or another degree. As it happened, the other military spouse communities offered something to defray the costs: scholarships to tech boot camps. For women.I did more research and found information on several other scholarships, programs and groups to help aid the transition into tech—for women. I tried to tell myself it was just branding; the goal seemed to be to level the playing field in an industry dominated by men. But I couldn’t shake the thought of being prescribed a label of "woman" just to get access to those career resources.Ultimately, I decided not to pursue a career in technology.

I came away feeling demoralized and foolish.

I Want a Professional Community That Acknowledges All Marginalized Genders

I’ve quietly taken my leave of many military spouse communities. But even outside those spaces, I regularly run across professional communities that appeal to me until I see they are branded for women and only women. When I look at the websites or social media from these groups, I see women with big smiles. Their attire is feminine. Long hair cascades down their shoulders and, if their hair is short, it still retains femininity. They hug each other, exchanging knowing looks as they bask in community, understanding and sisterhood. When I see womanhood in this context, I’m witnessing the celebration of a culture that is not my own. It is wonderful, but it is not mine. Somehow, being short, lacking facial hair, having round thighs or something else about my body prompts strangers to call me “ma’am.” I don’t understand why my body is viewed as my identity. When I try to wear women’s clothes, I want to rip the soft, thin fabric off. It hugs curves that I view as a quirk of biology rather than an integral part of who I am. When I see women smiling in solidarity with each other, I understand they are experiencing something that I do not. I’ve learned those spaces aren’t for me. The trade-off is too steep, and I can no longer stomach invalidating my sense of self for a shred of professional community. And yet, what I want out of a community feels minimal. I want a good faith effort to use gender-neutral pronouns for me. And I want collegial friendships that don’t involve assumptions about my experience based on my gender. I want a community where we can acknowledge the impact of gender on our professional lives while including people of all genders. It doesn’t feel like a lot to ask for, but I haven’t found it yet. I’ll keep looking. But in the meantime, I try my best to forge professional connections with individuals rather than groups. Maybe one day we’ll have a community of our own.

Being the Mistress's Daughter Makes Me an Outsider in My Family

I am the daughter of a mistress. Nothing prepares you for the gravity of this realization, especially when you find out as a child.For the most part, and on a surface level, my childhood was pretty great. I had a brother and two sisters and dogs. It was an idyllic life—so idyllic that I never really gave much thought to how my siblings came to be. In my small and unevolved mind, we were the byproducts of my parents. I believed my mom was their biological mother and my dad was their biological dad.I’ll never forget the day that all changed. I was about 7 years old. During our scheduled break in primary school, conversations in our class group turned to our birthdays and those of our siblings. When it got to my turn, I proudly and happily told everyone. But my classmate quickly noticed that my siblings and I were too close in age to be blood-related and told me so. He proceeded to grill me in front of the others and called me a liar. I was livid. I didn’t want to believe him. Still, I couldn't shake the uncomfortable feeling that he was right. For some time before that encounter, certain things had happened that led these questions to take root. I had wondered why their skin was fair but mine was dark or why my extended family was hostile toward me or why my brother and sisters always kept me at arm's length. These questions constantly played in my mind.In many ways, finding out that my brother and sisters were my half-siblings lifted the veil. Things that I had ignored and neatly tucked away in my mind began to resurface. From that moment, it felt like the existing chasm that I was once blinded by in my family became apparent. All of a sudden, I began to understand why, underneath it all, I had always felt like an outsider in my family.

When I found out, I wanted to confront my parents, but I didn’t dare.

I Couldn’t Confront My Parents About Their Secret History

Before my mother, my dad was married to a woman from the same ethnic group. They had three children: a boy and two girls. Somewhere along the line, he met my mother, who had a different ethnicity than him. They fell in love and began a relationship that eventually led to marriage. At that time, tribalism was a big deal, so marrying a person of a different race wasn't encouraged and, naturally, my dad's family had issues with the whole thing.While the details surrounding his first marriage—or how he ended up with sole custody of the kids—are murky at best, my parents did everything in their power to raise us as one big happy family. Truth be told, I don’t even remember how I met my siblings. Still, I was happy to live in this particular harmonious reality. But like with all things, life had other plans. When I found out the truth about my siblings, I was angry. I was angry because it became clear as day that my mother was the other woman. Even as a child, I understood what that meant, and I felt shame.When I found out, I wanted to confront my parents, but I didn’t dare. For one, I was a child. And two, I was a child of African parents growing up in an African home, where you dared not question your parents. Besides, how do you bring up the topic of your mother being a mistress? To this day, my dad has never outright said his children were my half-siblings or acknowledged his past or the coldness of his family toward me and my mom. Still, my mom, in her own way, has dropped hints about what we were.

I Will Never Have the Same Relationship With My Siblings as They Have With Each Other

Looking back, the cracks were always there. Like the time I was called dark and ugly by my aunt or the time I was hauled off in the middle of the night from my grandparents' house in the village to stay in a roach-infested hotel.Back then, I didn’t fully understand what was happening, but as I got older, my mother filled in the blanks. In one of the limited bonding sessions we had, she told me what really happened that night. The story goes that we left the village because of a huge blowup between my dad and his family. Knowing that we would be visiting, they had brought another woman from the same ethnic group for him to marry. But he refused to budge from his decision to marry my mother.Instead, he cut off his family and we ended up in a hotel. Eventually, they reconciled, but I have never felt welcomed. I watched as my dad's family accepted my other siblings, showering them with affection, while largely ignoring me and giving me the cold shoulder. I never got to experience their generosity, and try as I might to have a relationship with my aunts, uncles and grandparents, I was greeted with the air of “know your place.”What's worse was that the distance I felt with my extended family had begun to take root with my brother and sisters. Between them was a palpable love and understanding, full of inside jokes and a sense of togetherness. But those feelings were never extended to me. I was jealous and desperately wanted to be a part of their crew, but I always felt shut out and was effectively told that I wasn’t a part of them.Perhaps this is why my mother was so hard on me. I never understood why, as a teen, she would harp on about how I had to work hard because eyes were on me, judging me. I got the feeling that any misstep on my part reflected on her. If I was a good child, I would be accepted. I didn't have the luxury of making a mistake. I had to be perfect, and if I wasn't, I had to put up the appearance of being perfect. Years later, I now understand that this was her fucked up way of proving she belonged in the family.

I was called dark and ugly by my aunt.

It Hurts Knowing I Will Never Have a Real Relationship With My Half-Siblings

While I love my parents, I hate what they did because affairs are never simple. They leave broken families, mistrust and anger in their wake. But most of all, they are a cowardly way out with consequences that can’t be ignored. What's more, my parents’ determined silence on the whole thing pisses me off. Whenever I try to broach the subject, I am shut down. I am fed crumbs that never nourish or satisfy my inquiries. Save for a few revelations here and there on my mother's part, I have nothing. This incessant desire on their part to keep a faux-united front has led to splintered relationships. Their reluctance to talk about what happened led to one of my sisters wanting nothing to do with me and my mom. Even though we were never close, her decision hurt. Still, I understand why she did it and can’t blame her. As for my other siblings, I have accepted that I will never fully be part of their lives in the way they are with each other, so I accept the relationship we have now.As for the rest of my extended family, I have made the decision to sever our relationships. I was tired of their hateful, vindictive nature and their thinly veiled threats. Coming to terms with this decision was hard, but in all honesty, I was tired of fighting to be seen and accepted, especially by people who did not want to see or accept me. And while family is great, it isn't worth sacrificing my self-worth in order to be accepted.

My Painful Encounter With Homophobia in a Kenyan Government Hospital

Being a journalist, I have, on several occasions, written about homophobia and the numerous struggles the Kenyan LGBTQ community encounters daily.To survive in the largely conservative and homophobic society, gay people in Kenya are forced to live a rather secretive life and forego many things, including religion, education, family and employment. Most churches reject LGBTQ people; they face discrimination in schools, forcing many to drop out; many get rejected by families once they come out as gay; and government institutions are reluctant to employ gay people.Just like in many African countries, the Kenyan public detests gay people to an extent of seeing them as outcasts. In Kenya, gays are held in utmost contempt. The Kenyan constitution lists healthcare as a human right that should be accessible and affordable to all Kenyans without any form of discrimination based on religion, gender, age, social status or tribe, but for gay people, this right is often and openly disregarded and violated. Under Kenyan law, homosexuality is outlawed, and government institutions and the public take advantage of this to humiliate, intimidate, harass and extort people believed to be gay or gay-friendly.In Kenyan public hospitals and prisons, homophobia is rife. Ask any gay person in Kenya and they will tell you the two places they would wish not to visit are public hospitals and prison.

Just like in many African countries, the Kenyan public detests gay people to an extent of seeing them as outcasts.

I Was Refused Treatment Because I Had an STI

My experience with homophobia in a public hospital was a nasty one: It almost drove me into committing suicide. I’m thankful for the swift action from a gay support group; otherwise, mine would have been a nasty story.What started as a simple rash on my genitals turned out to be the worst experience of my life. For weeks, I had experienced some sort of discomfort in my ass when walking or while sitting. The rashes had spread all over my genital area, and this got me worried. At first, I had assumed that maybe it was a simple allergic reaction that would disappear with time. But as days passed, the condition worsened, and after a month of suffering in silence, it was evident that something was not right.Visiting a government hospital confirmed my worst fears: It turned out that I had contracted a sexually transmitted infection.Tests confirmed that I had been infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), which resulted in acute anal warts.But at that point, the news of an STI did not even shock me like the reception and treatment I received from the healthcare workers at the government-run health facility. “Huyu ni shoga; kujeni muone shoga,” (meaning “this one is gay; come and see a gay person”) the doctor shouted. Shoga is a Swahili word and Kenyan slang for a gay person.“So how did you get infected with a disease for women?” the doctor thundered, sending shivers down my spine.Within no time, the doctor’s room was full of nurses who had come to witness my predicament.At this point, my wish was only one: that the earth would open and offer me an escape route out of the room.For a moment, pain from the anal warts had disappeared and was replaced with pain from the mockery and ridicule I was receiving from people who ought to have given me consolation, comfort and care.“Here we don’t treat gay people,” one nurse shouted from a corner of the room.“This is satanic. These people [gays] are the cause of all calamities in this country,” a second nurse interjected.All this time, nobody seemed to be feeling my pain. To them, I deserved it.Being a journalist, I summoned some courage and confronted them, asking them to view me as any other patient and not as a gay person.“With all due respect, doctor, just look at me as any other patient and treat me with dignity,” I thundered, but the good doctor paid by the taxpayer could hear none of it.The doctor stood his ground and, as if adding salt to injury, told me that the STI was a “punishment from God.” He ordered me out of his room and directed me to go and seek traditional medicine because according to him, my sickness was a curse from the heavens.“Stop having sex with men or you will die like a dog,” were the doctor’s words that followed me as he ushered me out of his room.Dejected and abused, I walked out of the hospital with two things: a story (as a journalist) and pain (as a patient).

Within no time, the doctor’s room was full of nurses who had come to witness my predicament.

I Got the Assistance I Needed Through an Underground Organization

I felt unwanted and unworthy. With the pain (both physical and emotional) still raging, I moved into self-isolation in my house, far from the world which seemed to work against me.For two weeks, alone and helpless, I thought of taking my own life, but on seeing my mother’s portrait hanging on my wall, a second voice would tell me to hold on.And with the effects of the STI becoming worse, I had to break the silence and find a solution.Through my journalistic connections, I approached a local secret gay support group in our city and search for help. The group, which operates secretly for fear of government crackdown, links LGBTQ people in need of medical assistance to private clinics and medical personnel who offer LGBTQ-friendly services. The group runs secret safe spaces where LGBTQ people who are sick, victims of violence or those being targeted can seek refuge.“Your condition seems serious,” the director of the lobby group told me before I could even narrate my ordeal to him.I was booked in one of the rooms inside the safe house, and within an hour, a venereologist was at hand to examine my situation. I was put on intravenous fluids for three hours as tests were carried out. I commenced treatment immediately after the doctor recommended that I could still receive treatment at the safe house without being admitted to a hospital.After a week of treatment, my body was on a full recovery path, and hope was restored.Thankfully, the lobby group paid for my treatment and even got me enrolled in a gay support group to help heal the trauma caused from my experience at the government hospital.

LGBT-Friendly Health Centers in Kenya Provide Life-Saving Care

Hundreds of gay people in Kenya, especially those from rural areas where support groups are scarce, are forced to endure pain and suffering in silence any time they contract STIs for fear of facing homophobia in government hospitals.However, in the last 10 years, civil organizations and rights groups are teaming up with doctors and medical personnel to set up health facilities and centers that are LGBTQ-friendly to offer services to LGBTQ people who face victimization in government hospitals. The centers offer free testing for all sexually transmitted infections, treatment of STDs, referrals for specialized treatment, free antiretroviral drugs, free condoms, as well as offering free lubrication fluids. Apart from offering medical services, the LGBTQ-friendly centers also act as counseling points for gay couples, safe centers for gays people who are in danger, as well as training centers.Such free and accessible services being offered by such organizations are coming in handy for the LGBTQ community in Kenya so they no longer must battle infections and sickness in silence for fear of being victimized in government hospitals whenever they seek treatment.

I Worship Jesus, but I Don’t Fit in My Church

“People bond more deeply over shared brokenness than they do over shared beliefs.” – Heather KoppI worship Jesus Christ. Let’s get that straight right away. I cannot remember a time I didn’t believe in this long-haired, white-robed man who walked on earth for 33 years, was crucified, died and buried. He, from the very beginning, was tangible, reachable and relatable.Even as a little girl, I knew with a kind of knowing only a child has there was somebody all-powerful watching over me; not a measly cloud or a spiritual universe but a real, living, breathing God. I didn’t need to be convinced or brainwashed by those fanatical extremists who shoved their religion down your throat like a bad meal. I only knew a Jesus who loved me unconditionally. That was enough.Thus, in later years, I was surprised, sort of, that my Christianity wasn’t up to snuff with my fellow Christian soldiers. I wasn’t the right kind of Christian. I didn’t fit into an agreeable box. I was an odd shape of the puzzle that didn’t seem to fit anywhere, any place. And although I tried to squeeze into the frame, I understood I was becoming an inauthentic version of myself.

Some have said I’m not up to Christian guidelines because I voted for Joe Biden.

My Political Beliefs Don’t Make My Faith Less Valid

Some have said I’m not up to Christian guidelines because I voted for Joe Biden, while several members of the church community voted for the twice-impeached, disgraced Donald Trump. I’m positive I’m the only person in the church parking lot with a Biden/Harris bumper sticker, which, by the way, somebody drew mustaches on with vivid black marker. The joke was on them because Kamala was still dazzling with whiskers.I marched during the #MeToo movement, as well, wearing my “nasty woman” T-shirt proudly like a badass with my girlfriends. I raised my fist high, Gloria Steinem-like, shouting, “Time’s up! Together we rise!” Furthermore, I support LGBTQ rights, which are basic human rights, and I have a massive, melting heart for men and women who live inside the wrong bodies.I do not agree that if people believe differently than me, they will be descending into the pits of Hell. If so, six million Jews, along with my beautiful comrade Anne Frank, would be there. I cannot comprehend this cruelty, this kind of brutal God.The God I worship is a lamb, a shepherd, a redeemer and a papa whose lap I sat on for one straight year when my sister was murdered. He comforted me, held me and brushed my long auburn hair. When he promised he would restore my soul and lead me beside the still waters, he wasn’t lying.

I Often Wonder Why I Stay at My Church

I’ve been a member of the same Baptist church for 25 years now. In the past few months, I’ve been contemplating why I stay, why I haven’t walked away, why my heart resides inside the pastel walls even though I don’t fit in any longer.And I’ve come up with several reasons.For one, the charming church ladies, the prayer warriors, the pioneers, who prepared a room for me after my first and second babies were born. The white hair cuties smelling of Avon perfume and Folgers coffee who served me lukewarm tuna hotdish with crushed potato chips, Swedish meatballs, lavish relish trays, rosettes and buttercream cupcakes on delicate white doilies. They cared for me, supported me and, of course, fed me well!I stay because my parents were on the financial board, the Christian education board and headed up the nursery. As a child, I wanted to sit on the hard, wooden pews with them and sing “How Great Thou Art” and “Bless This House.” Even as a grown woman, I wanted them to be proud of my dedication and attendance every Sunday. I want to hold onto the family traditions I grew up with. I want it all.I stay for my late pastor’s wife who read Anne Lamott’s Traveling Mercies and Rachel Held Evans’s Searching for Sunday, my favorite “this is what kind of Christian I want to be” authors. I recall when she told me she had just finished Lamott’s book, how I grasped both of her large hands, jumping up and down in the sanctuary like an excited child who had just been validated and acknowledged for exactly who she was.

I stay for all the wrong reasons.

I Wish the Members of My Church Gave Me the Same Respect I Give Them