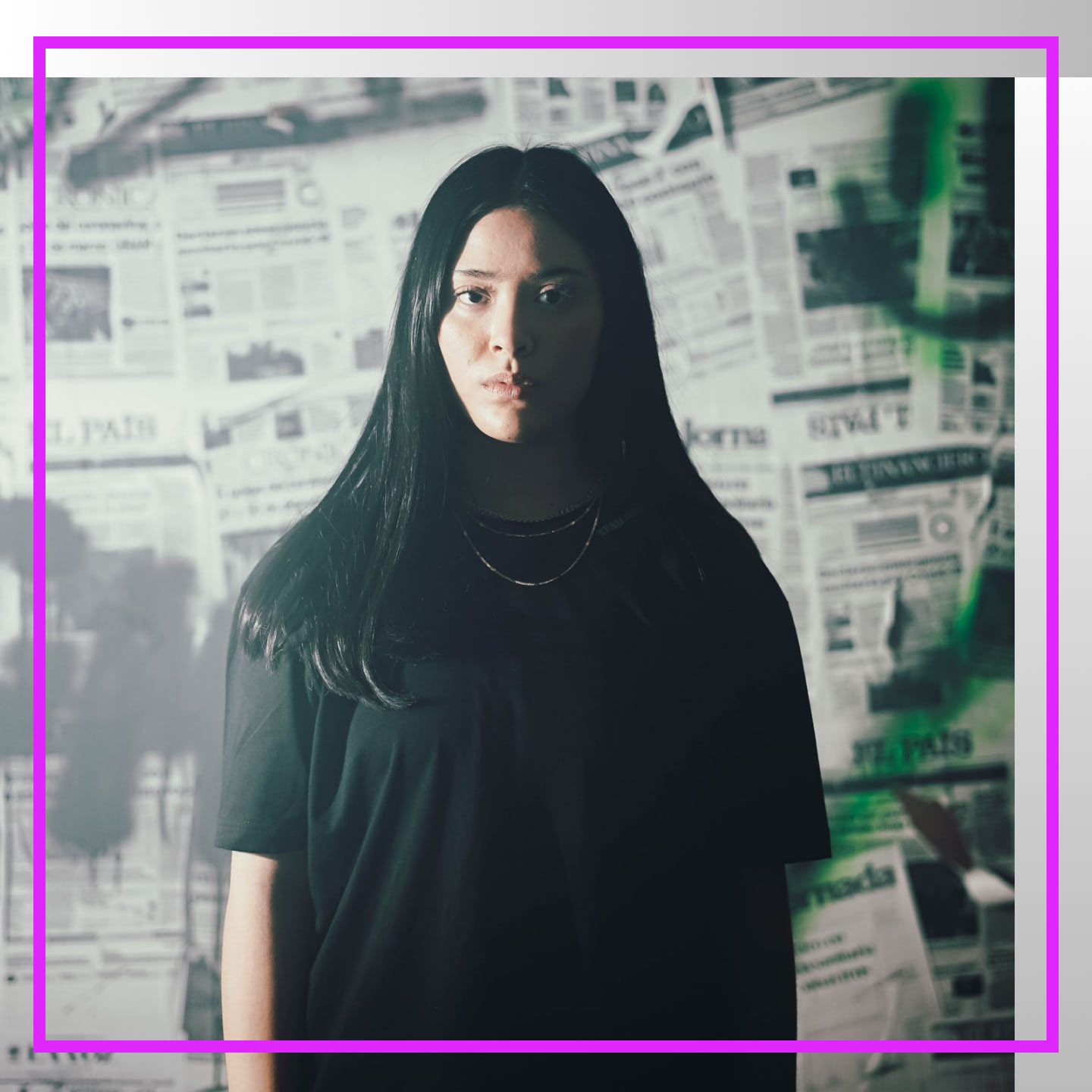

I Survived a Boy Band Twitter Mob|A music critic is shocked by the vitriol they receive on Twitter.

I Survived a Boy Band Twitter Mob|A music critic is shocked by the vitriol they receive on Twitter.

I Survived a Boy Band Twitter Mob

I knew even before I wrote it that the article was going to cause trouble. When I pitched my editor at a very well-known global culture-and-lifestyle magazine about covering the very young and very zealous fandom of a popular British boy band, one of the first things out of her mouth was, “You know they’re going to come for you, right?”I knew she was right. It was 2012, right around the time social media stopped being a digital novelty and started figuring out what it was good for—things like connecting global pop-culture fanbases and organizing them into hate mobs to go after anyone who they saw as attacking their favorite boy band/movie franchise/video game. It was the dawn of the stans. I’d seen them coming for other critic friends. I supposed this might be my time.

There were more than a few death threats.

What It’s Like to Have Twitter Gang Up on You

My article went live in the morning, and at first, the response was fairly mellow. The only negative feedback in the comments came from snobby music nerds accusing us of stooping to cover boy bands just for the clicks. I’m very sympathetic toward overly passionate music fans, especially teen girls, who historically have taken a lot of undeserved shit for liking music that middle-aged men don’t consider worth taking seriously. I hoped that came through in my writing. Maybe the fans reading the piece were picking up on it, I thought. By lunchtime, it seemed like my worst fears were overblown.Then, somewhere out in the digital wilds, the right fan with the right Twitter following found the article and didn’t like what they read. The replies started rolling in, hundreds of them, the notifications on my phone blurring together into a steady buzzing that I had to silence because it was driving me nuts. None of them were nice. Over the course of the afternoon, I was called every bad thing a 12-to-14-year-old girl could think of to call someone, dozens of times over. There were more than a few death threats. Years of being a critic—and all of the mean comments I’d received on articles at the much smaller paper I’d been writing for prior—had taught me to have a thick skin, and at first, it was easy to brush the insults off. But after you’ve been called an ugly, talentless bitch a few dozen times, it’s hard not to feel a little hurt.And then it stopped, as suddenly as it started. I never heard another word from them.

It’s Not Just Boy Band Stans

Being a critic has always meant being criticized back. People are passionate about the art they love and often very quick to defend it against perceived slights. Artists—aside from a small minority who are too self-actualized or successful to care—are even more sensitive. (If you write honestly enough and for big enough publications, you will eventually make an artist you admire personally hate you, which is a weird marker of success in the crit world.) Critics, like lawyers, have long been seen as cultural parasites who exist only to tear down people with “real” talents. Before the internet, living with that knowledge, plus hate mail from anyone you pissed off enough for them to write a letter, was just the cost of being a critic. Since then, things have gotten a lot more intense. Comments sections let people say the worst things they can imagine to call someone, anonymously and at no cost. Social media made it easy to organize the mass harassment of people whom you don’t agree with. With so much of our lives online now, a motivated fan can easily piece together where you live, who you know and what your biggest vulnerabilities are. Writing criticism sometimes feels like legitimately dangerous work these days. Since the boy band incident, I’ve had a number of notably toxic interactions with people online over my opinions. I reviewed a budding pop singer’s album for a widely read music website and said I thought some of the songs were decent, but overall, the project didn’t live up to the lead single (which I emphasized in the review that I really loved). The singer personally organized a Twitter mob that struck while I was in the middle of an already incredibly stressful destination wedding I’d been dragged to by my partner at the time. A decade ago, I wrote a critical essay about a very big jam band for a very big men’s magazine—basically saying I gave their music an open-minded shot and couldn’t get into it, but if they float your boat, good for you—and I still get remarkably vicious hate emails from it. (Don’t ever let hippies fool you into thinking they’re actually as mellow as they claim.) When I wrote a blog post for a big supermarket-checkout-lane entertainment magazine criticizing a certain pop icon for co-opting the images of dead civil rights icons for her album marketing materials, a superfan left a series of long, disturbingly detailed comments underneath the post about myself, my partner and my cat—and accused me of being a pedophile. These are just the more extreme examples that stand out against the steady hum of low-level abuse that I’ve absorbed over the years. I’ve been called every insult in the book, had people invade online spaces that I thought were safe and been told to kill myself so many times that it’s stopped being shocking. My skin is much thicker than it used to be, but I’m also more cynical, as much as I hate to admit it.

Writing criticism sometimes feels like legitimately dangerous work these days.

Why Is Criticism Worth It?

Writing about music or movies or TV or video games now means accepting that you will be on the receiving end of the worst that people can dish out online, from insults to death threats to doxxing, and that the better you do at your job, the worse you’ll get it. If you make a big enough splash—like critic Anita Sarkeesian, whose work criticizing sexist tropes in video games launched an army of revenge-seeking fanboys—the threat of violence can bleed over into real life. Between that, the elimination of staff writer positions at publications and cratering rates for freelancers, a lot of good critics are dropping out of the game entirely, and young, pop-culture-literate minds are taking jobs in safer, more secure industries like marketing.A lot of people would say that’s no big loss. But good criticism doesn’t just point out good art or admonish the bad (although in our age of oversaturation, that help can be incredibly valuable); it also holds a mirror up to the society that art springs from and helps us untangle our mass subconscious the way a therapist can show us behaviors we don’t even realize we have. Good criticism doesn’t exist in opposition to art; it uplifts it, makes it stronger, helps us to engage with it more deeply. Good critics love art and artists and other people who feel just as passionately about it as we do. That’s what keeps us writing, even through the abuse.