The Doe’s Latest Stories

My Vaginismus Story: Understanding My Pap Smear Fear

I’ve avoided gynecologists for most of my life, but in the times that I’ve tried to overcome my fears and get a full examination, there was no way that cold speculum was going in. Until recently, I’d never experienced internal self-pleasure or penetration of any kind. It was only after my fifth try at penetrative sex that I realized my vagina wouldn’t allow anything inside. I didn’t understand what was wrong with me.

My Religious Upbringing Is a Contributor to My Vaginismus Symptoms

I’d been indoctrinated to believe that sex before marriage was a sin. I grew up in an Eastern Christian Orthodox family, one that was incredibly religious and my parents were really strict. When my father saw me hugging a male friend goodbye one day in high school, I received a huge lecture about not touching boys and that hugs were forbidden. In the years since leaving my parents’ home, I’ve become more progressive about everything, including sex, but my own relationship with it was the one thing I couldn’t let go of. I understood the limitations of my thinking around sex, how heteronormative it was and how patriarchal ideas like purity and virginity are. I became sex-positive for everyone else but not myself. It was too entrenched in my mind that if I did it, something terrible would happen. I couldn’t get the thought of my parents’ faces, my grandmother’s face, even my late grandfather’s face out of my head whenever the thought of it came to my mind. Like many other heterosexual Christian girls, I found the loopholes that eased my conscience. I engaged in other forms of sexual activity with long-term boyfriends but always drew the line at penetration. Although I still felt guilt, I managed to convince myself that at least I wasn’t crossing the ultimate line (even if my politics around sexuality told me otherwise).

I didn’t understand what was wrong with me.

I Experienced Vaginismus in My Marriage, Even Though I Felt Safe With My Husband

My boyfriend at the time didn’t have the same puritanical views on sex, but he understood what I needed and respected that. We were together for eight years before we got married. In that time, we got to know other aspects of our sexuality and intimacy that were fulfilling. Yet here I was, married and on my honeymoon, doing it with my husband, and something bad was happening. I hadn’t waited all this time to have sex just to continue not having it. I was in denial for a few months about what was happening. I thought if we tried enough, I’d get it right eventually. Sex became a high-pressure activity, one that I needed to overcome rather than enjoy. Sadly, in my mind at the time, all the creative and pleasurable ways we engaged in sexual intimacy before marriage became unimportant to me. I needed to get over the line for it to count.

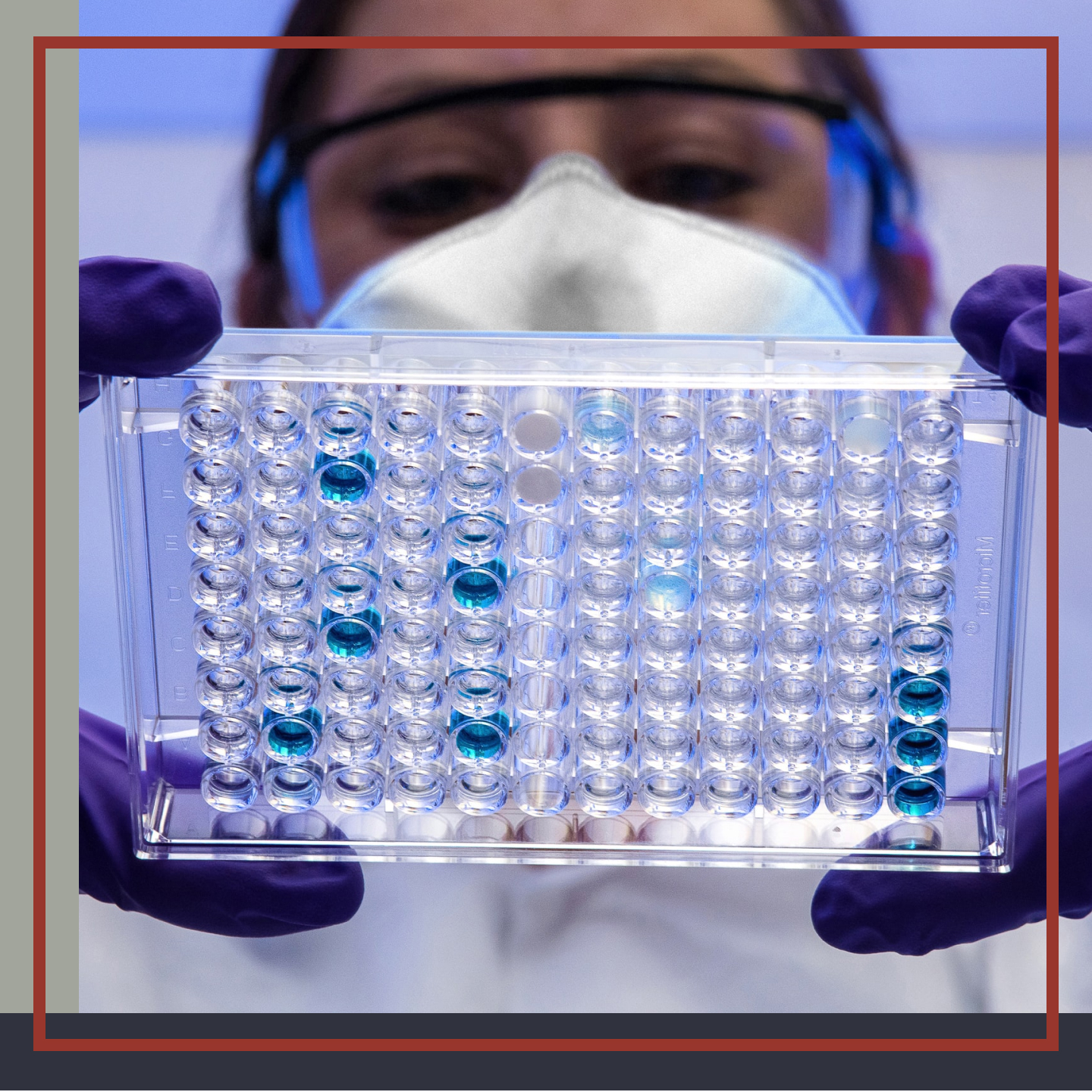

I Was Unable to Do a Pap Smear With My Vaginismus, and My Doctor Further Traumatized Me

I didn’t know until after a visit to the gynecologist that I had a condition called vaginismus. Vaginismus is a condition that results in a trauma response to vaginal insertion of various kinds. It’s an automatic tightening of the vagina, one that you have no control over. Unfortunately, the doctor who diagnosed me wasn’t the best person to deliver that news. During our exam, I mentioned it was my first time seeing a gyno and that I’d waited for marriage to have sex, so I’d never done a Pap smear. “You did the right thing,” she said. That was the first red flag, but I just ignored it because I thought she was trying to be nice.I was convulsing and fighting as she held my legs open while she tried to insert the speculum. The gynecologist was visibly frustrated and warned me that I had to relax because she didn’t want to sexually assault me—not the best way to calm someone down. When my body refused, she gave up and sternly told me that I probably have sexual dysfunction. Ashamed and in shock, I put my clothes back on. I confided that I was having trouble with sex. She asked me if I had experienced any sexual trauma in my life. I hadn’t, at least not in the capital-T sense of Trauma, but the ways I was taught to associate sex with danger had traumatized me in more subtle ways. Then she told me that if I don’t work on this, my husband would leave me. I brushed this comment off because I knew better. I’d never let this kind of thinking get to me before. I was secure in a loving and dynamic relationship. I believed my pleasure was just as important as my husband’s, and I know that sex is more than just a penis penetrating a vagina. But hearing those damaging sentiments from a woman and her way of handling this very delicate situation was traumatizing. I walked out of there thinking I could never go back to a gynecologist again.

Ashamed and in shock, I put my clothes back on.

I Learned More Online and in Therapy About Vaginismus Than I Did From My Gynecologist

When I got home, I started Googling all the things I was experiencing and found a whole online community for vaginismus—the condition I now had a name for. Being able to name it was a relief, and finding out how many people around the world experience it made me feel so much less alone. If the gynecologist had been more informed about this, she could have helped me with information, different therapies and, more importantly, hope. Unfortunately, when I finally found the courage to go and see another doctor, she was just as ill-informed, and I felt like I was the one educating her during our consultation. Why would a whole medical specialty dedicated to helping women not be aware of something that causes so much physical and psychological pain for so many women?Luckily, I had the internet and a psychologist at the time. Through my online community and therapy, I’ve figured out that the way my community growing up handled the topic of sex was a form of trauma and that the boyfriends I’ve had along the way who pressured me into sex had only added to it. Dealing with the psychological side of the problem meant that I had to completely abandon the idea of penetrative sex and find pleasure in other kinds of sex again. Dilators have helped me ease the physical side somewhat, to the extent that I’ve managed to have a few pain-free and pleasurable experiences of penetration. Still, the thought of a Pap smear makes me anxious, and the worry that I may never be able to have one remains on my mind.

Confronting My Vaginismus Trauma and My Pap Smear Fear Head-On

Recently, I opened up to my GP about my condition. She’s kind and supportive in general, so it felt safe to tell her. She was sure she’d be able to work through it with me, and I felt hopeful. The next time I had a consultation, she told me we should give a Pap a try. Feeling relaxed and optimistic, I happily got on the bed and breathed deeply. As soon as the cold of the metal touched my vulva though, I seized up, and my legs immediately shut. My doctor was incredibly patient and tried to soothe me, breathing with me and gently trying to keep my legs open as she told me to put my hands on hers. Together, we approached my vulva again with the speculum. Again, every muscle on my body felt like it was contracting. I didn’t want to give up. We’d come this far, and I was so sure we were going to get it right this time. After about half an hour of trying, she told me we should quit and that she didn’t want to re-traumatize me. As soon as we stopped, tears came streaming down my face. I couldn’t stop crying. It was a shock reaction. I was embarrassed that I couldn’t control my emotions, but my doctor was as supportive as ever, and she helped me to calm down. “You haven’t failed,” she told me.

I Haven’t Completely Overcome Vaginismus, but I’m Not Alone in This Fight

I haven’t been back to try again, but now I'm more empowered than before. The internet once again helped me realize that I wasn’t alone. People have come up with their own therapies, bought their own speculums and developed whole programs to send to the doctor before a visit so that they can be informed about vaginismus. It’s quite amazing what people can do for each other, even with no formal organization or protocols. The field of medicine has always ignored women’s pain. They need to catch up to us now because we’re not waiting for them. Until then, I’m continuing to explore my body, find patience with it, heal my traumas and do what I can to break the cycle so that the next generation of young people can spread awareness, prevent and treat vaginismus.

I’m a Med School Dropout Turned Acupuncturist: My West-East Perspective

My personal struggles with physical and mental health took my lifelong dream and reshaped it into something I never could have imagined. Ever since I was little, I’ve wanted to be a doctor. My propensity for academia, curiosity with the human body and desire to be successful kept me on that path through high school and college, all the way to one of the top medical schools in the country. But it came with a price. I ended up in an environment that was so competitive that no one cared if I was even OK. It wasn’t until years later that I would find my true calling: acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine. But luckily for me, none of my Western education has gone to waste, as the future is integrative medicine, and I am here for it.After graduating college with two degrees, working in an ER, doing research and crushing the MCAT, I was accepted to four amazing medical schools, and parts of my ego were at an all time high. I chose the California school for prestige and in-state tuition. But all the while, I was struggling with my mental health, so the competitive environment chewed me up and spat me out. My depression had gotten really bad after isolating to work on the applications, and my family situation was also very tumultuous, so I was feeling really unsupported and unprepared before school. I had a bad experience with a therapist/psychiatrist team that broke patient confidentiality with my family and misdiagnosed/mismedicated me. I sought solace and a sense of community in the rave culture and self-medicated with drugs and alcohol. But this just made things worse.By the time I got to medical school, I could barely focus enough to go to classes, so they started having me see the school psychologist and psychiatrist. They decided it would be in my best interest to go on medical leave of absence and return the following year. That meant leaving my on-campus housing, the only refuge from my toxic family environment, so it really didn’t do me any favors. I would drive down to school to continue seeing the therapist and the doctor, but my mental health just kept getting worse and worse.The therapist would listen to what I had to say but never really made any suggestions, goals or plans. He never recommended substance abuse treatment, group therapy or anything, really. The psychiatrist seemed burnt out and overworked, like he was bothered by the fact that he had to see me on top of all his other responsibilities. He didn’t think critically and went by the misdiagnosis from the previous practitioner. Even when I tried to explain why it was wrong, he didn’t listen. He didn’t care. They didn’t care about me, my progress or my success.

They didn’t care about me, my progress or my success.

I Found My Own Path Using Acupuncture and Eastern Medicine

I got tired of this and decided to forge my own path to feeling better. In the year that I had spent applying to medical school, I was starting to cultivate my spirituality via yoga and meditation, so once I left med school, I got a job at a yoga studio to stay busy and learn more about it. I practiced a lot and eventually did a 200-hour yoga teacher training. I started learning about spiritual practices, seeking something to help me manage my mood. I was introduced to Buddhism, which helped me raise my life condition and, I feel, led me to my current path: acupuncture. I wasn’t seeking acupuncture. To be honest, I had tried it a few times and been underwhelmed. But I was seeking a healer with some kind of ancient wisdom because I felt that would help me with my issues. I was still cycling through different psychologists and psychiatrists with little improvement. I was also having physical issues, like heartburn and chronic bladder irritation, that I needed help with. And last, but certainly not least, I needed to figure out what to do with my life. By this time, it was too late to go back to medical school, and I was working a dead-end desk job that I hated. Soon, I found an Ayurvedic (Indian traditional medicine) practitioner near my work who just happened to also be an acupuncturist. In our first session, this woman spent two hours with me and absolutely blew my mind. She got my entire physical and socio-emotional history and wove me a story about how the physical symptoms I was having were related to the emotions that I’d had because of the way I was raised. Everything was starting to make sense. Then she took me into the treatment room for a guided meditation, some acupuncture on my chakras, cupping, Thai massage and even some energy work. For the first time in a long time, I felt cared for.I felt like I could really open up to her, so I told her that I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. She asked what my background was, and I said medicine, and she literally said, “Why don’t you do this?” It was a lightbulb moment for me, and I left the office knowing I would study acupuncture. A few weeks later, I enrolled in acupuncture school, and five years later, I graduated and am preparing to get licensed. During the course of my education, I have witnessed and experienced numerous phenomena that are nothing short of miracles. A couple doses of herbs and an excruciating pain goes away. A few needles and a wonky digestive tract is fixed. Some energy work and months of anxiety and insomnia fade into a memory. I love what I do and the power it has given me to help others and myself.

Everything was starting to make sense.

Find Doctors and Practitioners That Actually Care for Your Health

So you’re probably thinking that I have sworn off Western medicine for acupuncture and Chinese medicine. But just like Western medicine, Eastern has its downfalls. I’ve spent hundreds of dollars on herbs and treatments that didn’t make any difference. I’ve gotten bruises from the needles or felt tired after treatments. One time, I was so out of it after acupuncture, I rear-ended someone. Another time, I gave myself a panic attack by taking herbs that interacted with a medication I was on. There were times when I was in a lot of pain and tried so desperately to only use natural methods to feel better with such little relief, but as soon as I caved and went the Western route, I felt so much better. While some practitioners, myself included, are very quick to refer to the Western doctors, I’ve had the other experience when I needed to be referred and wasn’t. Indeed, the downfalls of alternative practices are that they claim to heal everything. There are Eastern alternatives to things like antibiotics and antidepressants, but I believe it’s important to weigh the cost of these treatments and the ease of use when determining the best approach for an individual. If everyone had unlimited resources, we’d suggest acupuncture and herbs daily until they felt better, but all of my experiences have made me a realist and an advocate for an integrative approach. Especially when it comes to acute conditions—that’s where Western medicine really shines. Don’t deny yourself technology if you really need it. That is something I would like to change about the culture of alternative medicine and why I’m passionate about advocating for integrative medicine.As far as choosing practitioners, my takeaway is that there are incompetent, competent and exceptional practitioners in every field. There are providers that will help you and providers that will hurt you. I am by no means an expert in Eastern or Western medicine, but I’ve had a lot of experience as a patient of both. I’ve been saved by both and burned by both. The common thread was the doctors that cared who helped me the most. So when you’re looking for a practitioner of any modality, find the one who you feel like really cares, and that will make all the difference.

How I Overcame Yo-Yo Dieting and My Bad Relationship With Food

The first time I experienced body shaming was at a pool party when I was nine. I was wearing a new, hot pink one-piece bathing suit that my mother had bought when suddenly one of the boys splashed water my way and yelled, "Hey, Big Bird!" At first, I didn't understand the reference until he pointed to my stomach and said, "Skinny legs, fat stomach—just like Big Bird!" He squawked and flapped his arms before returning to a group of giggling kids by the pool steps. I glanced down at the wet, pink fabric that clung to my bulging stomach and was reminded of a brightly dyed Easter egg.Clinging to the rough edge of the concrete pool, I waited until the group of kids moved toward the diving board to make my escape from the water. Once inside the house, I quickly changed into dry clothes, then sat by the refreshment table where I stuffed fistfuls of potato chips into my mouth to numb the shame.I never wore that bathing suit again.My parents were always picky about my looks—they often poked my puffy belly to remind me I needed to stop snacking. I resented it but accepted it because I assumed it was their job to judge me. Weren't all parents concerned about their child's appearance? But being teased by my peers brought on a whole new level of shame that I was not emotionally equipped to handle.Around this time, I started really studying myself in the mirror (specifically the way my clothes fit) and rethinking my wardrobe. I hated that I was the tallest girl in my class, the last picked for relay race teams during recess and the first to rush home because I didn't want the boys yelling "Big Bird" or "Fatso" when I ran down the cracked sidewalk to my house.

I never wore that bathing suit again.

Yo-Yo Dieting Led to a Period of Disordered Eating

By the time I reached the sixth grade, I had begun the first of many diets. My sister and I did it together, counting every calorie we consumed and carefully measuring our food on a tiny kitchen scale. To my surprise, I quickly lost ten pounds, and the adrenaline rush I felt from my parent's compliments outweighed any cravings I might have had for junk food.But like many dieters, I found calorie counting too restrictive after a while and was quickly sucked into years of yo-yo dieting. As a result, my body became a human accordion; sometimes, I was thin, basking in the attention of high school boys. Other days, I felt fat and hid behind oversized clothing. The war with my body continued through my college years as I allowed the numbers on the bathroom scale to dictate my mindset. If the numbers were higher than I considered acceptable, I'd live on 600 calories a day. If I lost weight, I rewarded myself by binging on ice cream, hamburgers or whatever fried food I could get my hands on. It wasn't long before I discovered that I could eat as much as I wanted as long as I purged afterward.During this dangerous time, it never occurred to me that I was torturing my body in my quest to be thin, allowing this self-destructive behavior to continue for years until I finally met someone special and got married.

My Unhealthy Relationship With Food Resurfaced After Having Children

My husband was always generous with compliments, assuring me that I was beautiful and loved no matter what size I was. His easy acceptance of my appearance made me feel comfortable in my own skin for the first time since childhood. So instead of obsessing about my body, I focused my energy on starting a family and hit the gym regularly as a healthy alternative to control my weight.But nine years and four children later, the pounds crept back on. When I looked at my reflection, I hardly recognized myself. I thought the excess weight was muscle mass from my workouts. Still, there was no denying the swollen belly that triggered the same insecurities I felt at the elementary school pool party. Terrified of gaining more weight, I increased my cardio workouts and persuaded my doctor to prescribe weight loss medication. The drugs worked—I completely lost my appetite and dropped 40 pounds in two months.Certain my days of compulsive overeating were done, I reveled in my new smaller size and never tired of hearing people tell me I was getting too skinny or that I needed to gain a few pounds—this just fueled my desire to continue cutting more calories. Being thin was unchartered territory for me, opening new doors to a life I never knew existed. People smiled more at me, men flirted and women complimented my appearance. The anxiety I'd felt when I was overweight disappeared, replaced by a sense of confidence that I'd never experienced before. It didn't matter that the medication made me extraordinarily thin and jacked up my heart rate; all that mattered was that I looked skinny.

My Obsession With Body Image Rubbed Off on My Daughters

My obsession took its toll—the self-destructive cycle repeating itself in my daughters, who also had an unhealthy obsession with weight. As teenagers, they frequently examined their bodies in the mirror, tugged at their jeans and lamented the numbers on the scale. Their behavior reminded me so much of myself at that age, and I couldn't bear to think that they might spend the majority of their lives obsessing over their weight as I had. I felt as if I'd failed them by allowing them to grow up watching me criticize my appearance and for letting them see how my weight had defined me. I wanted them to focus on what was more important—their character and their health, and they needed to learn it from my example.I stopped cold turkey on the pills, and within weeks, my heart rate returned to normal as my weight increased. I tried not to panic when my clothes became a little snug, reminding myself it was best for my health.And it would have been if I hadn't let the old habits of compulsive eating creep back into my life.

I Became Naive About My Yo-Yo Weight Gain, and My Body Paid the Price

A series of events occurred that triggered me to numb my feelings with food. First, it was the grief of my mother's passing, which resulted in a falling out with my siblings. Then, I saw my son hospitalized for an addiction to nootropics. After that, I felt as if I was unraveling one pound at a time. In those four years, I gained 70 pounds and stopped caring how I looked. My life was in chaos, and the only solace I found was in the comforting arms of food.Despite the weight gain, I still embraced body positivity no matter how scary the escalating numbers were on the scale. I kept reminding myself that true beauty came from within and that it shouldn't matter how large or small I was, or what people thought of me, as long as I was happy with myself. So instead of staring at my expanding waistline in the mirror, I focused on the physical features that I felt were positive—good skin, nice eyes, a pretty mouth and a great smile. My mantra was, "If I feel good on the inside, then I'll look great on the outside!" But even though these words were repeated in my head daily, I was subconsciously disguising my body in larger clothing and avoiding full-length photos on social media.My body wasn't going to let me get away with that unrealistic way of thinking. It started first with my feet—they ached if I stood for too long during the day. Next, my doctor diagnosed plantar fasciitis and had me wear shoe inserts in addition to sleeping with special boots for my feet. After the foot pain subsided, I decided to exercise outdoors and trekked the mile trail near my house, only to limp back home after my left knee gave out.I was also exhausted all the time, falling asleep at my computer when I should have been working. The nights were worse—I couldn't get comfortable in bed because no matter what position I chose, the excess body weight pressed heavily on my chest, making it harder to breathe. My husband complained about the loud snoring and finally moved out of our bedroom and onto the couch. I thought of the people who used CPAP machines to help them sleep and vowed that would never be me—yet I continued to fool myself into thinking I was still at a normal weight. I believed that a few extra pounds wouldn't affect my health and that only people with morbid obesity had serious health issues. I wasn't at that point…yet…so why worry?

My Wake-Up Call to Break the Yo-Yo Diet Cycle

There were other problems occurring: A mammogram ordered by my doctor revealed two cysts inside my left breast. After doing a little research, I discovered that the statistics for breast cancer were higher for women my age who were overweight.More tests were ordered—blood work that indicated I was pre-diabetic and needed cholesterol medication. An inconclusive urine test required an ultrasound that later revealed that my gallbladder was loaded with stones—most likely from years of drinking alcohol and eating high-calorie foods.I woke one morning and stared at my puffy reflection in the mirror, no longer recognizing the dull-eyed, pasty-faced woman before me. Instead, what I saw was the face of my older sister, who had died years earlier from complications of her obesity.It was a moment of sudden clarity; my inability to face my obesity was costing me my health and leading me down the same destructive path that had taken my sister's life. It was the wake-up call I needed to change my unhealthy eating habits.

When I looked at my reflection, I hardly recognized myself.

I'm Finally Learning How to Have a Healthy Relationship With Food and My Body

Oddly, during the years I was thin, I suffered from body dysmorphic disorder, believing I was too fat despite being dangerously underweight. And then the reverse occurred once I became obese—there was a complete disconnect between myself and my body. As a result, I thought my weight was average and continued to give in to cravings for fattening, sugar-laden treats as a reward for my positivity.The only way to stop letting food control me was to think in terms of getting healthier, not "skinnier." I joined a popular weight-loss program that included a special meal plan and worked with a coach who helped me think of food more as a way to nourish my body rather than blocking unwanted emotions with large amounts of fattening snacks that did nothing to sustain me. Whenever I felt like straying from the plan, I called my coach or read inspirational stories on weight loss, which helped me to stay on track.I also joined a support group of people just like me with body image issues and eating disorders that helped give me the courage to stop my dependence on food for numbing myself. With support from family and close friends, I dropped the extra pounds in six months and no longer feared the allure of fattening foods. Instead, there was a sense of relief that was more freeing than the weight loss itself. By changing my life, I added more quality to it.I look better now, but more importantly, I feel better. The bodily aches, snoring, heartburn and pre-diabetic conditions have all disappeared with my weight loss. I am not too thin or overweight, but I am the best version of myself. I'm right where I need to be: healthier, stronger and happier—and currently the proud owner of a hot pink bathing suit.

My Endo Belly Is So Bloated I Look Pregnant

As society becomes more aware and accepting of the reasons why women can’t or don’t want to have children—whether for personal, political or environmental reasons—it’s become increasingly taboo to ask someone if they are pregnant. Still, in the past three months, I’ve been approached twice by people asking when I’m due.I’m not pregnant. I live with stage-four endometriosis, diagnosed through surgery earlier this year after ten years of extremely heavy periods and debilitating pain. It’s a full-body disease that is often misinterpreted and dismissed as “hormones” or “bad periods,” but its effects reach far wider than just bleeding. The most notable are reduced fertility and the inability to have children biologically. Endometriosis has been found on the lungs, brain and liver. In my case, they found extensive “deep infiltrating” cells growing in the lining of my stomach, which has contributed to intense gastric issues that were formerly misdiagnosed as IBS. A hallmark of both IBS and endometriosis is extreme bloating and swelling of the stomach caused by an inflamed abdomen, along with digestive issues that are intensified by the presence of the cells causing the enlarged stomach. Often it makes people with severe endometriosis look like we may be carrying a child.

I'm desperate for kids.

The Worst Part of My Endo Diagnosis Is That I May Not Be Able to Have My Own Children

Having my bloating mistaken for a baby bump has left me feeling ashamed about the way my body looks to others, but I’m more heartbroken by the knowledge that having a child of my own is a reality I will most likely never experience. I'm desperate for kids. I’ve always wanted tham, and I have a kind of innate feeling inside me that says I’d be good at mothering. I’ve worked with children in various capacities over the years, and whether teaching or nannying, I find caring for children to be incredibly fulfilling. Although I would happily have one of my own now, my partner and our current life setup say otherwise, but there is also the larger issue that I probably can’t have them anyway. During the operation where my endometriosis was diagnosed, the doctors also found a golf-ball-sized cyst on my ovary. Through sheer luck, and a lot of skill on the surgeon’s part, they removed it without having to take my ovary too. This is a rare occurrence in endo surgery, particularly if the operating team lacks specific experience, which is common. Endometriosis affects one in ten people who menstruate, but the number of patients far outweighs medical professionals trained in the specific treatments we need. In my surgery, they also found four centimeters of endometriosis covering my bowel. This was left untouched during surgery as a bowel specialist is required to be in the operating theater for its removal, as it’s deemed a higher-risk procedure. After coming round from surgery, high on IV morphine and still in excruciating pain, my surgeon showed me images of the inside of my womb covered in black speckles: the endometriosis. “It looks like your womb is inhospitable,” she said, “but there’s always IVF if you want to give pregnancy a go.” And with that, she was gone, leaving the images on my bedside table and wishing me a speedy recovery, saying we’d meet again to review in six months time.

Strangers Assuming My Endometriosis Belly Is Pregnancy Hurts Me Deeply

When the woman standing across the stall from me at the Saturday farmers' market asked if I was having a boy or a girl, I so badly wished I could say, “Yes, I can’t wait to meet my new daughter.” Instead, I felt my cheeks redden, my eyes cloud and my hands let go of the items I was going to purchase. I walked away clutching my boyfriend’s hand. I took to Instagram, tried to share the experience while veiling it in humor, to connect with other chronically ill friends who’ve had the same kind of interactions. I laughed about it and hoped my sadness would go away. But every night for the following week, as I drifted off to sleep at night, I thought of all the things I should have said to that woman and all the outfits I should wear to hide my bloating better. I read the statistics, looked up the cost of IVF and considered what I would do if I couldn’t make a child of my own. I’ve always been open to adoption, which aligns with the way I view the world. I grew up in an unconventional home, so I’m not adverse to making a family outside of the tradition.

Will I love my child the same if I can’t conceive her myself?

The Possibility of Not Being Able to Conceive My Own Child Haunts Me

It wasn’t until someone told me I probably cannot create a child the way most other couples do that I started to realize how much I wanted to experience pregnancy. I know, instinctually, I will love and mother any child I bring into my family, whether through adoption, birth or surrogacy, but it’s that intense feeling of growing another life inside me that I don’t think will be replicated any other way. For now, there is no baby in me—just a lot of gas and misplaced cells swelling my stomach to appear as if I am expecting. The people asking if I’m pregnant don’t know the pain I’m in or the string of questions I ask myself before I get to sleep every night: Will I love my child the same if I can’t conceive her myself? Will I be content? Will it ever be good enough?

The Body Positivity Movement Isn’t Just for Women

I consider myself to be a body-positive person. Gaining or losing a few pounds doesn’t really matter to me. Although I would be lying if I said it was something that I was born with—I had to learn it with the help of female empowerment and body-positive spaces online.After having my son in my mid-20s, I vowed to teach him what I had to learn on my own as a teenager: that his appearance was not representative of his value. That he’s much more than that. I felt even stronger about body acceptance now that I had a post-baby belly pooch and a few extra stretch marks. On the days that I struggled—on one occasion, feeling sad after a daring attempt to squeeze into an old pair of jeans—I found myself trawling the internet once again for feminist mantras, self-love quotes and pictures of normal female stomachs. Like a hug from an old friend, I was comforted.Something furious ignited within me as my son grew. I was determined to be a conscious parent, doing everything in my power to help my son to be a confident and self-assured kid in a world of Instagram, photoshop and body shame. On a warpath of empowerment, I armed myself with kids’ books about positive self-esteem and corrected myself when I used male-centric compliments, instead emphasizing his kindness rather than praising his tough exterior. I was learning. I still am now.Of course, despite my gentle push towards more neutral toys, he loved superheroes, so I indulged his interests and let him play with them, unaware that these buff characters would ultimately be damaging for his body image and contribute towards the narrative that men aren’t worthy or respected unless they are physically very fit.

What's missing is seeing real men's bodies rather than the sculpted, washboard, Greek-god abs in every movie and TV show.

My Son’s Superhero Toys Contribute to Toxic Masculinity

One day, he eyed the plastic lines etched into his action figure’s torso and asked me when a six-pack of his own would be appearing. At this moment, my heart broke. I knew that he was starting to think about his appearance and compare himself to the world. I didn’t want this to escalate into a deeper problem.I felt like I had failed as a mother. Where had I gone wrong?Naively, I had never viewed boys’ toys as problematic. Girls’ dolls are a different story, however, as the majority of us are familiar with how their tiny waists, breasts and heavy makeup teach girls to internalize this as ideal. On the other hand, superheroes and soldiers represent everything that men are told that they need to be—strong, infallible, a fixer of all problems. Essentially, a hero.It was like a lightbulb moment. “This is contributing toward toxic masculinity,” I thought. It didn’t feel right. Each action figure that my son owned had comically huge muscles, hyperrealistic bulging quads and vascular biceps, along with a sculpted six-pack. This is just as damaging as the girls’ dolls that parents tend to steer away from nowadays. In reality, a man would need a ridiculously low body fat percentage and a militant training regimen to maintain such a physique that these toys are perpetuating.

My Husband Got Hooked on His Body Image

I decided to do some research and found a worryingly empty space on the internet for men’s body positivity.Instead, it was disproportionately female, celebrating authentic bodies at unposed angles and the refreshing sight of unairbrushed skin. Lines, creases and stretch marks that felt as familiar as my own. I felt torn, as this female-led space helped me with my own body image issues, but I was powerless to change the fact that men’s normal flaws and diverse body types just don’t exist in the media.What's missing is seeing real men's bodies rather than the sculpted, washboard, Greek-god abs in every movie and TV show. The shirtless imagery that bombards us in every men’s lifestyle magazine.My motivations for a men’s body positivity movement weren’t just for my son. I had seen my husband struggle with his body image for years—at one point, his normal interest in working out spiraled into an obsession. I recognized my past self mirrored in him as he would pass by his reflection and pinch the tiniest amount of skin on his toned stomach. “I just need to get rid of this,” he would say, fiercely gripping anything he could around his torso.Helplessly, I watched as he would limit himself to just eating enough to meet his macros, some days drinking only protein shakes and exercising four, five, even six hours a day. My concern intensified as it escalated. I caught him taking dangerous fat-burning pills that he had secretly purchased from shady websites. Later, he confided in me that he was considering using steroids because, according to him, it was common amongst his friends.He was undeniably in amazing shape, but at the price of risking his health and falling into disordered eating behaviors, it was not worth the immense damage it was causing.

I couldn’t ignore that he was made to feel this way by society and the media.

We Need to Have More Conversations About Male Body Positivity

I couldn’t ignore that he was made to feel this way by society and the media.Men’s pressures to be ripped have been packaged as a fitness movement that is obtainable with normal gym habits. Actors and popular male fitness social media stars, who dedicate every waking moment to being in shape, often have personal chefs and trainers, and some use steroids to reach insane levels of being ripped very quickly. But they all declare that their muscular physique is the result of hard work and a good diet, which is highly problematic.My husband is now in recovery from his exercise addiction and complicated relationship with food. We tell our son that it’s OK if he wants to exercise when he’s older, that not everyone can get a six-pack. And that’s OK too. But more importantly, we emphasize the importance of practicing emotional honesty. While I can’t change the world alone, I can make small changes in my language and teach my son to be empowered and remain unphased by this outdated rhetoric, and encourage other men to share their stories.The facts are clear. Male body image needs to be discussed. Healthy doesn’t always look like a six-pack. Men are still valid and important if they’re not muscular. The notion of a “perfect physique” is not real.

My Mother’s Cancer Taught Me How to Navigate the Negative

It was the evening of October 27, 2020, when my phone rang. I was sitting in my college apartment in Gainesville, Florida, studying for midterms. On the other end of the line was my mother. I was expecting a catch-up call with my mom, but instead, my world stopped. Her words hit me like a freight train: “It’s cancer.” We cried, hung up, and then I cried some more. My mom—my best friend, my role model, my everything—had just been diagnosed with stage-three colon cancer, and I was hundreds of miles away. I’m the youngest of three—my two older brothers are my biggest blessings. My parents have always made sacrifices for us, and they have proven to me that love is unconditional. Thankfully, I grew up in a happy home. My family has always been there for each other, supporting each other's dreams, providing shoulders to cry on—we’re close. So that day, when I was receiving calls from my mom, dad, brothers and grandma, there were a lot of tears. We’re also a very strong, prideful family, so when I heard my favorite people crying on the phone, far away with nobody to hold, it was hard—quite possibly the hardest thing I’ve ever experienced.

Cancer dances between the lines of life and death but can also be used as a force to bring joy.

My Mom Is an Icon of Generosity

I’m fortunate enough to be able to say that life has not met me with much difficulty. I grew up in a loving home, made good grades, was involved in school, had friends and never felt the weight of deep sadness. This unfamiliar weight was so heavy on that day that the scale nearly broke. My mom, the most important woman in my life, had cancer and I couldn’t even hug her. On top of being so far away, we were in the middle of a global pandemic. With my mom being the genuine people-person that she is, it broke my heart to think she couldn’t see her friends or hug them—she couldn’t even leave the house. Despite the negatives stacked against her, she remained positive. My mom is the type of person who would wake up at 4 a.m. every day so she could prepare a fresh lunch for her kids to take to school, the one who cooks extra food for her coworkers. Upon walking through our front doors, she will always ask if you are hungry. (My friends have learned to arrive at our house with an empty stomach.) She hosted dinners for the cheer team, even after her daughter graduated. She always puts others before herself, and she is transparently honest. My mom is strong—the strongest woman I’ve ever met. Her motto is “Fighting!” because no matter what challenge she faces, she is prepared to fight through it and come out stronger—a quality that she has instilled in me. Now that she has cancer, the word “fighting!” gets thrown around like confetti. It may sound silly but hearing that word is what gets me through each day. Because we live in a small town, everyone knew about the cancer soon after the diagnosis. And since my mom is a pillar in our community and opens her kitchen and home to everyone, countless people wanted to help however they could. With so many people in her corner, my mom started to realize how loved she really is. As letters, flowers and meals poured in, my family grew even more thankful to have the life we do. Not only were we blessed to have our community in our corner, but we were blessed to have each other. In the process, we grew closer and stronger than ever before, which I didn’t think was possible. I am reluctant to admit that I have an unhealthy habit of avoiding my feelings. The support I experienced from my friends and family was nothing short of overwhelming. I’ve learned how important feelings and emotions are, and I have grown strong enough to recognize and appreciate my weaknesses. Despite my past tendency to avoid my feelings, my family held me while I let them pour—even hundreds of miles away.

I’ve Found Strength in My Mother’s Will to Fight

It’s interesting how cancer dances between the lines of life and death but can also be used as a force to bring joy. It has inadvertently strengthened me as a person, making me more genuine, hopeful and happy. I went home to see my mom the weekend after the doctors diagnosed her and surgically removed the tumor. I got there the day before she was released from the hospital. Physically, my mom was weak. Mentally, she stood strong. Although exhausted, she walked into our home with a big smile on her face, clearly ready to fight like hell. While every part of me wanted to stay home and be with my family, I knew I had to go back to school. Upon returning to Gainesville, a switch flipped. I studied more, became more organized and focused on the things I could control. Part of my drive was fueled by my attempt to avoid thinking about my mom’s diagnosis. But most of it came from my mom’s attitude about her diagnosis. She’s going through chemotherapy—currently in month four. Every day, she sends me a message with hearts, smiles, updates and of course, “Fighting!” Each day, she indirectly shows me her strength and drive to beat this thing. I do the same in return. In this way, my mom and I feed off of each other. That’s what keeps me going. I’ve learned that it’s okay to hurt and that you’re stronger than you think. I’m lucky to have the support system I do and to feel comfortable sharing these types of feelings. In the beginning, I was genuinely concerned that I wouldn’t be okay sitting in my apartment or do well in school. But here I am.

Not a day goes by that I’m not met with fear regarding my mom’s health.

Pain Can Be an Incredible Teacher

Through this experience, I’ve developed a healthy way to cope and navigate the challenges thrown in my life. A lot of it has to do with that amazing support system, but a lot of it also has to do with my strength. I used to be prideful yet humble. Now I’m confident and proud. I’m not conceited, but I would be a fool to dismiss my strength. As I allow myself to be strong and proud, I also give myself the time to mourn. I’m not saying any of this has been easy; I’m just saying it’s possible. Becoming a more positive person isn’t about always being happy. It’s about allowing room for hope. It’s not that the sun shines brighter now, but it’s the fact that I can see that one slim ray that makes it through on cloudy days. It’s not making myself smile more often; it’s finding more reasons to smile. It’s not about wanting to be cancer-free one day, but having the hope to fight until you are. To be positive is not to look at life through this lens that optimizes everything and everyone. Life throws us challenges. It’s unpredictable and oftentimes defeating. To be positive is to recognize reasons to keep going through these times—to have hope.Not a day goes by that I’m not met with fear regarding my mom’s health. I’m not saying there aren’t bad days because there are. On those days, you can hurt, and you can hurt as hard as you need. Through that hurt, you’ll start to realize the inner strength you didn’t know you had. You can use the negative to navigate your way to the positive. There can be good times, even during the bad times.

COVID-19 Has Been a Lifesaving Panacea for My Complex PTSD

I spent the first decade or so of my life fighting for my life. It’s shaped me in ways I am only now beginning to understand, and, oddly enough, I have COVID-19 to thank for this recent clarity.Enduring almost daily sessions of “percussive counseling” on the fists of my alcoholic father left a legacy that lingered long after the bruises faded. Friends and family members at the time noticed things were wrong early on, well before I had a clue that things weren’t right. What they didn’t realize in describing my behavior was that I was exhibiting traits not dissimilar to those of POWs after they returned from war. While other teens laughed and joked and rushed around me squealing with joy, I became shy and reclusive, apathetic on my good days, near numb or counterintuitively irritable and anxious on the not-so-good days.I was clearly exhibiting symptoms of what we now know to be complex PTSD.

Severe Childhood Trauma Has Shaped My Adult Behavior

Decades later, this unacknowledged and unresolved malady had deviously taken the driver’s seat in my life, and almost every aspect of my world suffered for it. Personal relationships never ran too deep, romantic relationships were doomed from the moment things became too personal and my personal relationship with truth and reality became tenuous at best. Why? Because when children experience severe trauma at the hands of their family, it creates confidence and trust issues that far too commonly last a lifetime. The reason for these issues is now well researched and understood; how can you ever trust another human being when the very people who brought you into the world didn’t love and protect you from themselves? Worse, you can’t help but ask yourself a soul-destroying question: What kind of piece of shit am I if the people who are supposed to love me unconditionally treat me like garbage? Learning to trust and be confident in one’s own inherent value are essential elements in early childhood, teenage and adult psychosocial development. If we can’t learn to trust people around us, or if we have zero confidence in our own personal value, and accordingly cannot trust our own capacity to build and live a meaningful life, then we are doomed—at least in part.For too many years, facing these questions head-on wasn’t an option, so I did what many of us do at times of existential angst: I buried my head in the sand. Over the years, I tried almost every known means of quieting the spiteful internal voices and ignoring the dull ache that comes with knowing you’re betraying yourself by hiding. When alcohol didn’t cut it, I turned to pills and powders. When those failed, I turned to my GP and began relying on pills that alternately had me experiencing vertigo or suicidal ideation, sometimes both. The cost of this period of my life—where I was, for all intents and purposes, a duck, calm on the surface but churning madly underwater—was tremendous. Outside of learning to rely on three to four hours of sleep and experiencing epic mood swings, it cost me a couple of high-paying jobs, some amazing friendships, a marriage and almost my life after a failed suicide attempt.Clearly, things had to change. In my case, it took a global pandemic to force my hand.

What kind of piece of shit am I if the people who are supposed to love me unconditionally treat me like garbage?

The Pandemic Offered a Shared Human Experience

When COVID-19 struck, I was working in Eastern Europe, thousands of miles away from home, from family and friends, basically as isolated as you could be. To say I hit rock bottom would be an understatement; I spiraled like Charlie Sheen in Vegas. So I booked a flight home. What I discovered upon returning home a handful of months into the pandemic was that people I had previously seen as standoffish or elitist were clamoring for human connection. Everywhere I looked, I could see clear signs of anxiety, uncertainty and social isolation. What I was witnessing was my own reality played out on a global scale; I realized that my harsh daily reality in which I felt anxious and isolated due to C-PTSD was now a common malady. Strangely, this made me feel the most human I had felt in years; I wasn’t so different after all.This recognition of a shared (albeit anxious) human experience started making me question how much of an actual victim I was allowing myself to be as a result of my childhood trauma and how much personal responsibility I was taking to change my own human experience. A chance encounter with a genuine asshole forced me to ponder—if my indignant next-door neighbor could so swiftly become affable (if not entirely likable) in such a short period of time due to his social isolation and a deep-seated need for human connection, what possibilities were open to me for taking responsibility for shifting my narrative from victim to victor?What I’ve come to understand through forced lockdowns, remote working and a liberal amount of “me time” is that there is potentially a very real upside to COVID-19. The global pandemic presents us with a deeply personal moment in time to reflect, reassess and start to take responsibility for “the me I want to be” on the other side of this mess.

I spiraled like Charlie Sheen in Vegas.

I Began to Look at My Health From a Holistic Perspective

The first penny that dropped for me when forced to reevaluate my life (which included realizing that I was, in part, my own worst enemy) was that I wasn’t a happy or healthy person when I entered the COVID-19 pandemic. I dearly wanted to change this before I came out the other side. Central to this clarity was recognizing that I had never taken the responsibility to think about what a healthy life could look like because I was in victim mode.As a lifelong runner, I have always somewhat shortsightedly viewed my health through the lens of “physical” health, yet this “hurry up and stop” moment in history that we find ourselves in has forced me to take a wider, more holistic view of health to encompass other aligned aspects such as my emotional, social, spiritual and intellectual health and wellness.This shift in focus—this widening of my worldview as it pertains to health —has resulted in an astonishingly rapid shift in my priorities and day-to-day realities. Emotionally speaking, I’m more stable than I’ve ever been because I have accepted that only I can take responsibility for this next chapter of my life, and as such, I need to do more of what really matters to me.From a social health perspective, I’ve become conscious of the five people I spend most of my time with, even in lockdown. This has included me moving back into university studies to fulfill a lifelong dream of completing a doctorate degree in a field that will have a genuine social impact. From a purely physical health standpoint, I’ve started being more responsible for what I eat, for what media I consume and for how much time I spend outdoors exercising. All of this has led to a drop of 15 pounds, a gradual increase in the duration and quality of my sleep and a greater connection with my partner now that I’m calmer, living more purposefully and more present.

COVID-19 Has Given Me a Chance at Salvation

I will be brutally honest—deep introspection hasn’t been easy. It’s been far more confronting and oftentimes more unnerving than I ever could have imagined. But it’s made easier by understanding that I’m not so very different from other people. We are all anxious, alone and uncertain at times, which has in an odd way given me the confidence to keep peeking behind the curtain and continue to pick at scabs that I had previously done my utmost to ignore. The pandemic has reshaped the world in many ways that we would prefer not to have happened, but for me, it’s also provided a rare opportunity to slow down and take a good hard look at my life, my health and wellness and to start making changes. And as I continue to see the fruits of my labor, to experience the results of taking responsibility and positive forward action, my self-confidence is improving, which helps me build trust in myself and the world around me.COVID-19 isn’t going away anytime soon; neither is my C-PTSD. But amid all the uncertainty that surrounds us, I have more confidence that COVID is my moment of salvation rather than a harbinger of doom after seeing the results of the responsible changes I have made.

What It's Been Like Living With a Binge Eating Disorder All of My Life

I am in recovery from binge eating disorder and compulsive eating, something that has given me a lot of demoralizing experiences and which has touched every area of my life: my body, mind, sexuality, emotions and spirit. As a kid, food was my greatest escape from dealing with my dysfunctional alcoholic family. As early as the second grade, I was stealing and hiding food, and I can still remember the shame that comes from it. We were at my grandmother’s house, and I was eyeing the cake on the table. I had already had a piece, and my mom told me, “No more.” So when she wasn’t looking, I cut a piece and ran to the bathroom upstairs. I heard my mom coming, and I hid the cake behind the toilet on the bare floor. My mom found it, looked at me and asked, “What’s this?” I had no answer. I just told her, “I don’t know,” while inside I was embarrassed and totally ashamed. I got a lot better at hiding it after that, but I wasn’t really hiding any of it. My body continued to be the most obvious symptom of my compulsive eating.

Over the course of my four years in college, I gained over 160 pounds.

My Attempt at Coping With Binge Eating Wasn’t Any Better Than Binge Eating Itself

Later on, in high school, I wanted a change. I got a personal trainer and went on a super restrictive diet. When I came back from summer break, it was dramatic, like one of those teen movies. I was suddenly “hot.” Girls wanted to date me, and everyone told me how amazing I looked. I allowed the joy to overshadow what I was actually experiencing. With my new weight and my new looks, people treated me differently. I thought perhaps it was because I was treating myself differently. But “pretty privilege” and fatphobia are a real thing. So is the insanity that comes with trying to keep this “privilege.” What no one knew was that I was chewing and spitting my food out, exercising three hours a day and binging on bread before heading to the gym. I got a girlfriend, and it looked like I was having an amazing high school experience. In many respects, I was. And then it ended. Between the stress of starting college, a breakup and my ongoing family issues, I just couldn’t control it anymore. I started to binge again. Violently. Consistently. All the time. Over the course of my four years in college, I gained over 160 pounds, and I became addicted to pornography.This time in my life was such a blur. I walked around every day feeling ashamed that I couldn’t control my compulsive eating. I was obsessed with food and obsessed with my weight. As much as I wanted to lose weight, I didn’t have the willpower to stop my compulsive eating. During this period in my life, I really struggled with my masculinity, my manhood and my connection to my sexuality. Firstly, as a man, I thought I should be able to control my eating, that I shouldn’t be powerless over something so simple. As men, we don’t talk enough about the mind-body connection and the deep need for men to feel connected to their body. My frame was obviously not that of a “normal” sized man, and I certainly didn’t feel like any woman would be attracted to me. I objectified my own body by picking it to pieces and body shaming myself day in and out.So I shut my heart and my body down. While I was a compulsive eater, I was also a sexual and emotional anorexic, starving myself of some of the basic human experiences any young man can have that allow him to grow and explore who he is in the world. No one talks about this, but imagine the effects when you can’t see your own privates when you look down because of your stomach. We all deserve freedom from shame and a level of safety to explore ourselves with others in this world. When you are the one that shuts this down for yourself, you deny yourself the dignity of your own experience. You feel like less of a man, less of a person and less deserving of love. After college, I moved to Los Angeles, where I immediately hit rock bottom. I was choosing food over shelter. I reached a point where I was living in a hotel room and using the last hundred dollars on my credit card to binge. I would go to CityWalk, the downtown restaurant district outside Universal Studios, bouncing from restaurant to restaurant to food stand. Or I would go from one drive-thru fast-food restaurant to another. The food didn’t taste good, but it wasn’t about the food—it was about not feeling. I knew I couldn’t do it anymore. I didn’t want to kill myself, but I finally knew that I couldn’t use food to push down all the unmanageability in my life. I wanted to cut myself rather than feel the pain that I had never really learned to cope with.

Confronting My Overeating Coping Mechanism and Healing From Binge Eating Disorder

Growing up, my father had found recovery in Alcoholics Anonymous, so I was familiar with the concept. I was randomly getting lunch with a friend when she shared with me a little bit about her recovery as an alcoholic. I don’t know how, or why, but I started to consider that maybe there was a program for me. I looked up Overeaters Anonymous and called the contact for a meeting. A stranger answered, and I told them I needed a meeting. I asked if I needed to bring anything. She said, “Just know you are giving yourself the greatest gift you could ever give yourself.” I went to a meeting and started my recovery journey. I found a new home in Overeaters Anonymous.Through this journey, I lost over 160 pounds, and I’ve maintained a healthy weight for over 14 years now. Compulsive eating and recovery are no joke. It takes a lot of work on a daily basis that I have to continue to be honest about. Between being in a 12-step program, therapy and everyday life, I am confronted with the reasons I ate on a daily basis. They say if you want to know why you’re compulsively eating, stop compulsively eating. So I did. I’ve had to heal from all the resentments and hurts I’ve obtained over the years, all the hurts I stuffed with food. I had to allow them to come to the surface and grieve. I’ve had to allow myself to grieve. I’m 38 now, but at times, I’m still in many ways a 16-year-old with a lot of unmanageable feelings.As a result of this healing, I also found my way into Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous. I’ve had to look at my addiction to pornography and my struggle to feel intimate and safe with the opposite sex. Today, I am a vulnerable, honest man who lives with integrity and grace. I do it very awkwardly and very clumsily. But I do it, and it’s imperfect.

It wasn’t about the food—it was about not feeling.

How to Deal With Binge Eating Disorder Varies From Person to Person

Through all these experiences, I found myself becoming an advocate for those in recovery from eating disorders, specifically men and people from marginalized communities. In eating disorder recovery, we all come in many different sizes and experiences. For some, we need to eat more. For some, we need to eat less. Our bodies might be a symptom of our eating disorder whether we are extremely overweight or underweight. Our needs are different, and we need to make room for all the narratives.We live in a world that glorifies health and wellness in a way that for many is unattainable. And let’s be honest, privilege, race, gender, sexuality and economics all play a part in one’s ability to reach those perceived goals. But now we are seeing a beautiful counterculture develop that’s pushing back. We have the body positivity movement, the fight against fatphobia and new medical perspectives that say people can be healthy at any size. However, even in this counterculture, I have struggled to find my place and my story within the recovery community. Binge eating disorder was only recognized as an actual eating disorder when it was added to the DSM-5 in 2013. I believe we are only now starting to understand the experience.

Overeating and Eating Disorders Are About Much More Than Body Positivity

I have issues with some of the ways we’re approaching healing from eating disorders though. In my advocacy work, I’ve been told that I can’t talk about my weight loss. Or if I do, that I can only talk about it very vaguely, in order not to trigger other people. When I was at my heaviest and seeking help, I needed to know that weight loss was possible. I felt trapped in my own body, and I didn’t understand that it was manifesting the symptoms of my compulsive eating. I thought I was just a failure with a weight problem. But when people shared their experiences with me, I knew I wasn’t alone.The truth is, body positivity alone isn’t eating disorder recovery. Wanting to lose weight does not make you fatphobic, and each individual has a right to decide what role “health” is going to play in their lives. As a compulsive eater, my biggest flaw was my people-pleasing. I stuffed my feelings because I just wanted to be loved, because I didn’t love myself. And even in recovery, I can find ways to beat the shit out of myself. So I’m letting it all go. Appearing healthy is so much more than my looks or my blood pressure. Where am I mentally, emotionally, spiritually? Be willing to define that truth for yourself, and be honest about whether it is working for you. I don’t subscribe to body positivity for myself. I prefer body neutrality. I’m not always going to feel good in my body, and that’s OK. Those feelings allow me to connect to other issues that might be going on. My body and my desire to stay at a weight that feels comfortable for me does not make me fatphobic. It just means I’m having my own experience.We live in a culture that constantly promises the next big thing, whether it’s diet culture or even recovery culture. But I’m telling you, the next big thing is when you say “fuck it” and define what’s best for you yourself. What brings you peace? What keeps you balanced? What allows you to connect with you? That’s an obsession I’ll stick with—because everything else is just a distraction.

My Father's Blindness Has Changed My Perspective on Life

As I awaken each morning, my eyes open to a blurry view. The softened edges of my surroundings are washed with unfocused light. I take a moment to lay in the fuzziness before I reach for my glasses and begin the day. No matter what state I am in, in the morning—perky, lethargic, hungover—that moment humbles me. Like many, I have myopia—a vision disorder known as nearsightedness. The blurriness reminds me of how easy it is to be debilitated. Myopia, of course, is a widespread disorder. Millions of people have some degree of nearsightedness, donning glasses or contact lenses each day in order to interact with the world. Often passed down through some combination of mutated genetics, it tends to affect many members of a family at some point in their lives. This is true for me and my family, our conditions ranging from common to high-degree. While the rest of us have easily addressed it, my dad’s case is more complex. Through an extensive traumatic period, he became irreversibly blind, his journey telling a story of lost vision and hard lessons.

My Father’s Transition to Living Blind

My father’s visual deficiency stretches back to his childhood. During his teenage years, he wore thick-rimmed glasses, their round, heavy frame pressing into his nose bridge. Without them, he couldn’t focus on anything beyond a few inches from his face. He wanted, like most of us, to restore his sight. In 1995, he underwent corrective eye surgery to reshape his cornea. At first, it was successful; his myopia was effectively treated. But his underlying glaucoma, unbeknownst to all until after the recovery process, worsened. A long string of rescue and additional corrective surgeries followed, creating an archive of scars and recoveries. Ultimately, this turbulent course ended in 2010—he was officially blind. The intervening steps were not enough to correct this trajectory. Over time, his sight diminished until only a generic gray remained, like the uncolored slush of snow eroded by traveling footsteps. He has recounted this story to me several times, inflected with a tone of regret. He usually speaks with a matter-of-fact tone, but occasionally, a wistful sigh escapes. When he does, he’ll linger most on his initial decision to undergo surgery. Should I have done this at all, he poses as I listen quietly. Where did I go wrong? If either of my siblings or I mention laser eye surgery, he bristles, affixing his adverse result on us like a warning label. Scarred by his own harm, he protests in order to protect despite how safe the procedure is today. In his time, it carried higher risk; now, it is commonplace.

He refuses to let his blindness define him.

My Family and I Took on New Roles to Help My Dad

Soon after his becoming blind, my family and I adapted the home to be more blind-friendly. We organized our efforts around my father’s memory of the layout, like decluttering the common hallways and strictly organizing the kitchen. I was encouraged to see how he could maintain some agency when moving about, borne of years of lived experience. (This is why we can stumble, drunk with sleep, to the bathroom at night without a second thought.) But despite his intrinsic map, he still needed to form new habits. A toothbrush had to be placed in a specific direction; freshly washed dishes were arranged in the drying rack to avoid sharp edges; paper bills were folded based on their denomination. These measures represented his pragmatic approach, a means to an end no matter the difficulty. With the private interior under our control, the public exterior—unpredictable and irregular—was next. I became hyper-aware of every step or slope; any obstacle on the ground, like an errant rock or uprooted piece of sidewalk, that I would otherwise avoid without a thought became a potential tripping hazard. When we would walk together, I would guide my dad, acting as his eyes. Instead of watching distant buildings, I focused on the immediate ground before us. Occasionally, I would say, “Step up on this curb,” or, “The next set of stairs has five steps,”—moving through space was reduced to mechanical instructions. Now living away from my parents, I notice any manhole that is slightly ajar, a loose cobblestone or a sidewalk curb whose delaminated steel face juts out—urban dangers that remain as visual texture for most. Whenever I visit home, I resume the same role, guiding with my eyes cast downward, his inward. He refuses to let his blindness define him. Ever practical, my father still works as a physician while blind, albeit at a slower and more intentional pace. Guided by routine, he implemented workarounds like training his short-term memory and delegating more on others. He listens and memorizes each appointment and dictates key points back to his assistants to record. He had to adapt and quickly, for there was still work to be done. When I can, I aid in quotidian tasks like checking and reading aloud emails and reviewing recent financial activities. These seemingly benign new roles became portals to parts of him that I would not otherwise directly encounter. Relaying aloud each month’s gain or loss, a newly incurred debt or an email bearing a difficult subject were often uncomfortable exposures—news that we learned together in real time. It dissolved the mirage of the fortified parent and instead laid bare his vulnerability

I Learned the Value of Physical and Emotional Touch

I quickly learned how physical, for my dad, things became. The textures of everyday objects became apparent, his hands taking the place of his eyes. Each time we go grocery shopping, he handles the cart, and I will pass him various foods for him to handle and evaluate. I know he was never a big shopping enthusiast, but I want him to be engaged. This apple is too soft, he will say. This egg is cracked; go get another carton. When we pay and leave the store, he will insist on carrying the bulk of the weight, partly out of desire to help but also, I suspect, to occupy his hands. These handy tasks were a way to keep nimble, exercising his other senses when one was lost. But the most intimate form of this physicality was his grip on my arm when walking. This grip could take on different configurations: a solid, clamped hand; a few loose fingers; linked elbows; a clasp on my shoulder. In one touch, I would try to detect his overall mood—a firm hold could indicate nervousness or unfamiliarity, a loose one could mean comfort or aloofness. If it was cold and windy out, he might extend his hand into a pocket and we would essentially hold elbows. I felt these moments were glimpses into his mind that would otherwise go unnoticed—so much of what we emote in a day goes unspoken. While these micromoods were minute, I felt more closely connected to the thoughts lingering behind his visage. Now whenever I see him, I notice his gestures more and study his face longer, yearning to learn from this wordless language. In December 2020, we were walking to a restaurant for dinner. While my parents had been before, this was my first time. Approaching an intersection, I pulled myself forward, planning to cross the street. The closer I got, the harder my dad pulled back. I urged him to come with me, but he wouldn’t budge. Finally, when the light turned red, his grip softened. Frustrated, I turned to face him. The restaurant is on this side of the street, he said and led us in the right direction. Despite the darkness, his inner compass still points north.

Despite the darkness, his inner compass still points north.

I Started to Become More Present and Mindful

Being the son of a blind father has been and continues to be a lifelong lesson. It inspired me to learn about and advocate for disability rights. Tactility and materiality are important components of my professional work as an architect, where I create space for others. I have learned to not only see things more intently but also to listen closely, smell acutely and taste fully. How I take in the surrounding world is influenced by both his blindness and my own desire to consume everything in case I suffer the same fate. I am nourished by the tinge of orange zest, the crusted faces of old brick and the faint sweetness of a springtime wind. I am driven to feel whole through all my senses in fear of losing one. Now every morning when I awake, I embrace the blurriness. The haze is comforting, a respite from the hyperrealism of corrected vision. It soothes the mind to pull back from hard lines and sharp edges and instead wade in a soup of light and shadow. By focusing on this softness, I go about my day with clear sight and intention. But by the end, I anticipate returning to the blurriness, like a sun setting beyond the horizon, out of sight.

I Was Staunchly Pro-Choice. I Was Shocked When My Abortion Was Devastating

When I was 28, I had an abortion at eight weeks pregnant. It was going smoothly. When the doctor at the Santa Cruz, California, Planned Parenthood said, “Now just isn’t the right time for this spirit to come to Earth,” I shrugged in response, feeling uncomfortable. She seemed to be trying to comfort me.“I don’t think of it that way,” I said. “It’s just a ball of cells.” I’d always defended the right to abortion with a “no big deal” attitude—having an abortion wasn’t anything other than a safe medical procedure. This abortion was no different. It was the logical choice given my rocky romantic relationship. I didn’t think of the embryo as a human life. And I had no second thoughts based on how the abortion would impact me in the future. In other words, the idea that abortion was “no big deal” wasn’t just a political stance—it was something I believed through and through.I projected this view onto others too. I sincerely thought that no one, save for those indoctrinated by religious, pro-life values, had any reason to experience complicated emotions around abortion. When the young woman next to me in the recovery area of Planned Parenthood was gushing tears, I silently judged her. Why would she be upset about terminating an unplanned pregnancy? If she decided she wanted a baby, then she could have one later—once she’d thought it through a bit more. But an unplanned pregnancy would ruin her life. Buck up, dear girl!

I. Just. Needed. A. Baby.

I Suffered From Post-Abortion Stress Syndrome

That’s where I stood before things got weird and my world turned upside down. About one year after the abortion, I went from my normal, friendly, punk-rock self to having bouts of extreme jealousy of pregnant women and women with children. I seethed at baby strollers. I also despaired that I was likely infertile (with no evidence to support this), and I suddenly felt the need to name the baby I’d lost—the one who used to be “a ball of cells.” In fact, I couldn’t think about anything but this baby. Months into this surreal turn, I learned these feelings might all be grouped under something called post-abortion stress syndrome, or PASS, for short. PASS is a condition in which you have some variety of negative feelings—often of regret or guilt—after an abortion. Pro-choice scholars usually claim that the condition is entirely fabricated. Anti-abortionists usually claim that it affects a large proportion of women who get abortions. I had never even heard of PASS before I started feeling this way. I thought I might be losing my mind until I found a non-religious, apolitical support community of women online who had experienced PASS. But my experience with PASS, and in the PASS support group, turned my world upside down in another way, too. I now had to believe that abortion could have an emotional, or perhaps even biopsychological, impact on at least some women. Because I was one of them. And, thus, my "no big deal" dogma began to crumble.As part of my experience of PASS, I had something we in the support group called “replacement baby syndrome.” I. Just. Needed. A. Baby. It would be like bringing my lost baby back to life. In fact, I wanted this baby so much that I could no longer picture using any birth control more premeditated than a condom. My last relationship had ended, and while I didn’t want to mingle bodily fluids with just any guy I slept with, I also didn’t want to make 100 percent certain that pregnancy didn’t happen. What if my date and I decided to procreate in the heat of the moment? The best way to leave that door open was to avoid highly effective, long-term birth control options like an IUD.

Planned Parenthood Made Me Feel Excluded in My Path to Motherhood

My resistance to formal birth control is how I found myself, at age 29, arguing with my Planned Parenthood physician. I had moved to Oakland, California, and taken the train north to the clinic.“So, it says here you are not using a regular birth control method,” she said. “We should talk about that.”“I don’t want to talk about it. I’m almost 30 years old, and I want to be a mother. I wrote that on my intake form,” I replied.“Well, being a parent is harder than you think,” said the young doctor. “I don’t care if it’s hard,” I’d said. That’s when the tears began brimming. “You’re just saying this because I’m single and working class. You don’t think I should have a baby in my position. I told you before, I don’t want to talk about birth control. I came in for a pelvic exam!”I burst into tears, asked her to leave and proceeded to hyperventilate alone in the exam room.I know that plenty of Planned Parenthood doctors would have respected my wishes to focus only on the health of my vagina during the exam and not my reproductive capacities. Perhaps some would have given me information about local fertility clinics or “single mom by choice” groups so I could pursue parenthood safely. Others might have recognized that I wasn’t in a great emotional place to have a baby but might have referred me for therapy to discuss my options. But that isn’t what happened, and I was starting to feel that there was no place for me in the pro-choice movement anymore. I began regularly venting to my friends about the eugenic history of Planned Parenthood and the failures of the movement to acknowledge PASS or accept unconventional paths toward parenthood.

I suggest naming this new stance 'pro-option.'